About five years ago I wrote about vector format, and how it is not quite well suited to be used for application icons. Five years is a long time in our industry, and the things have changed quite dramatically since then. That post was written when pretty much all application icons looked like this:

Some of these rich visuals are still around. In fact, the last three icons are taken from the latest releases of Gemini, Kaleidoscope and Transmit desktop Mac apps. However, the tide of flat / minimalistic design that swept the mobile platforms in the last few years has not spared the desktop. Eli Schiff is probably the most vocal critic of the shift away from the richness of skeuomorphic designs, showing quite a few examples of this trend here and here.

Indeed it’s a rare thing to see multi-colored textured icons inside apps these days. On my Mac laptop the only two holdouts are Soulver and MarsEdit. The rest have moved on to much simpler monochromatic icons that are predominantly using simple shapes and a few line strokes. Here is Adobe Acrobat’s toolbar:

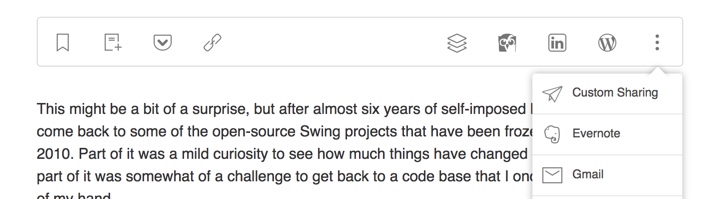

and Evernote:

This is Slack:

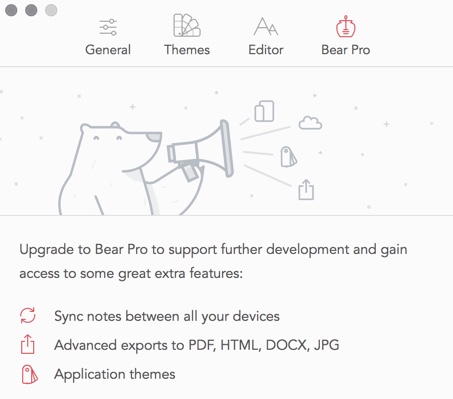

and Bear:

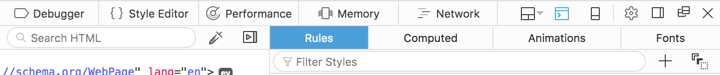

Line icons are dominating the UI of the web developer tools of Firefox:

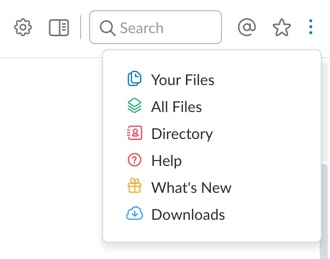

They also have found their way to the web sites. Here is Feedly:

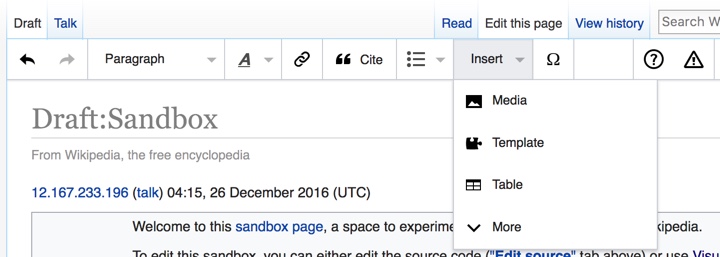

and Wikipedia’s visual editor:

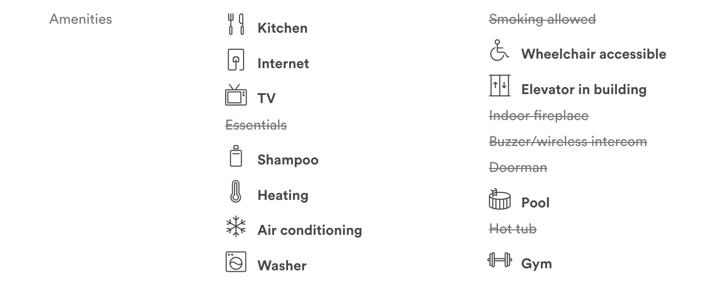

You can also see this style on Airbnb listing pages (with a somewhat misbalanced amenities list):

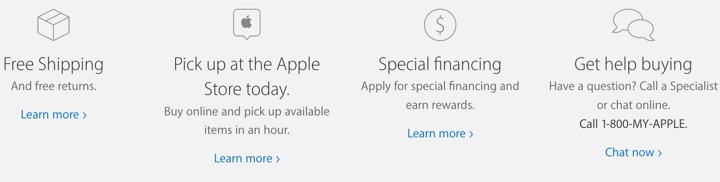

and, to a smaller extent, on other websites such as Apple’s:

Google’s Material design places heavy emphasis on simple, clean icons:

They can be easily tinted to conform to the brand guidelines of the specific app, and lend themselves quite easily to beautiful animations. And, needless to say, the vector format is a perfect match to encode the visuals of such icons.

Trends come and go, and I wouldn’t recommend making bold predictions on how things will look like in another five years. For now, vector format has defied the predictions I’ve laid out in 2011 (even though I’ve ended that post by giving myself a way out). And, at least for now, vector format is the cool new kid.

This might be a bit of a surprise, but after almost six years of self-imposed hiatus I’ve decided to come back to some of the open-source Swing projects that have been frozen in time since late 2010. Part of it was a mild curiosity to see how much things have changed in the meanwhile, and part of it was somewhat of a challenge to get back to a code base that I once knew like the back of my hand.

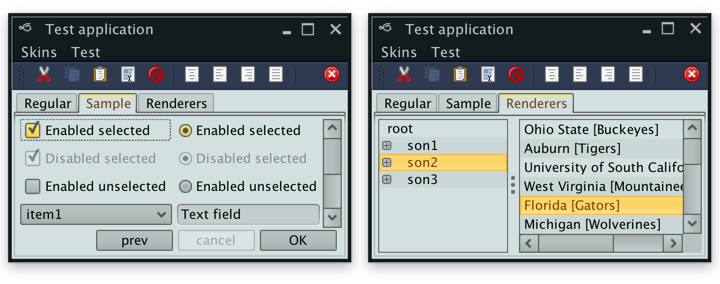

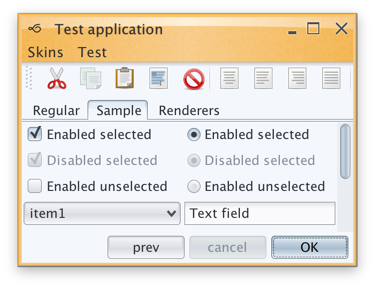

Before delving into the rest of this rather lengthy post, a fair warning. The images seen here are only meant to be viewed on high-resolution / retina / 2x-density screens. Otherwise what you’re seeing is a scaled down version of the original images that has little to do with the actual visuals seen on those screens.

Having said that, what is you see above is what I saw a couple of months ago on my 2013 MacBook Pro that has a Retina screen. Having spent the last four years looking at crisp visuals of pretty much all the native apps (except for Eclipse that is just now starting to get there, but then again calling Eclipse a native app is somewhat of a stretch), this was painful. There are obvious line artifacts, with the two most noticeable being the light outline along left/top edges of the main window and a darker horizontal line across the selected tab. But other that that, everything is just too blocky, pixelated and way too fat.

Two months later, I’m happy to report that Substance is a fully fledged citizen of the Retina universe. Given the amount of work that went into making that happen, the next release will have a version bump to 7.0 code-named Uruguay. The three big themes of this release will be as follows.

Hi DPI support

Searching the web for the initial pointers on Hi DPI support in Swing got me to this post from 2013 by Konstantin Bulenkov. Konstantin is the team lead at Jetbrains – the company behind the IntelliJ platform and all the apps built on top of that platform. Did you know that IntelliJ IDEA is a Swing app? If you didn’t, now you know.

Lucky for me, the code referenced in that post is part of the community edition of IDEA and is available under the quite permissive Apache license. And even though some part of that code is using reflection to query the underlying capabilities, if it’s working for IDEA with its hundreds of thousands of active users, it’s certainly good enough for me.

This code now powers pretty much all the pixels you see in Substance 7.0 – once again, the same warning about images that are meant to be viewed only on retina / high-res screens applies to all the images in this post.

Continue reading »

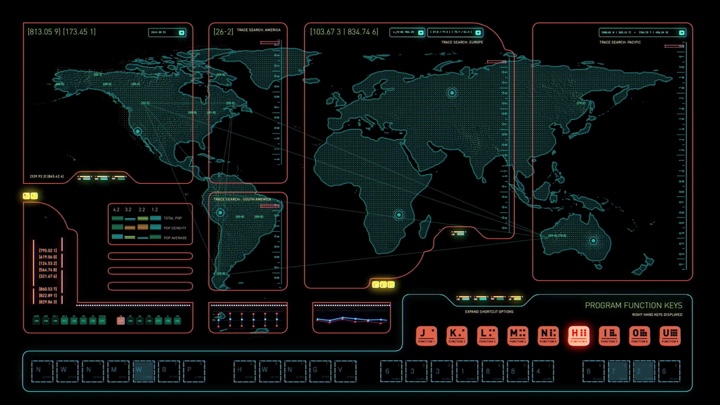

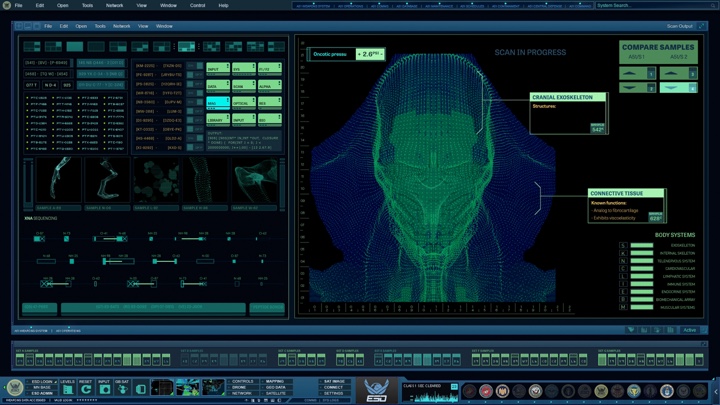

Continuing the ongoing series of interviews on fantasy user interfaces, it gives me great pleasure to welcome Derek Frederickson of Twisted Media. In this interview Derek talks about his early days in mid-1990s experimenting with Flash on the web, the screen graphics work his company has been doing on numerous episodic cable shows in the last ten years, and the software tools he’s using and how he would like them see evolve in the future. In between and around, we talk about his work on the recently released “Independence Day: Resurgence” that bridges the world of 2016 with the alien technology left “behind” in the first installment in the franchise, as well as glimpses of Twisted Media’s work on the upcoming “The Space Between Us”.

“Independence Day: Resurgence” Area 51 monitor test. Courtesy of Twisted Media.

Kirill: Please tell us yourself and how you started in the field.

Derek: I’ve been doing the things that I do today pretty much my whole life. I’ve always been interested in design, programming and animation…and that’s exactly what you need to able to do work in this field. Back in the early ’80s when I was in my single digits, I had a TI-99/4A. I went to school to study video production, and that helped with certain aspects of shooting, and understanding the whole flow of writing, capturing an image and editing. I was also a musician, so I have a lot of audio experience.

These three things combined helped me ever since. In the early ’90s I was doing CD-ROMs, designing interfaces, interactions, movements – a combination of all of those elements. And that’s still what I do now. If we do a command center or some sequence on a phone, it’s an interactive thing.

Derek and Tony on the red carpet premiere

Derek and Tony on the red carpet premiereThere’s an interesting thing about me deciding to name my company Twisted Media. It was just me, doing freelancing from time to time. And I got a random email from the assistant to Mark Franco who was the VFX producer that worked with Dean Devlin a lot. They were doing a show called “Leverage” and they were coming to Chicago, which is where I was living at the time, to do the show. And they literally saw the listing for my company in a creative directory and liked the name.

They asked me if I could do graphics for a TV show, and I was so excited after looking up the list of productions they’ve worked on, that included Independence Day and Stargate. So I wrote back “Yes, I can” [laughs]. That’s how it started. When Dean interviewed me, he knew that I was new to that field. But he also knew that the stuff that I showed him was very close to it. He recognized that I could do what was needed. And when he asked me if I could do that, I told him that I had waited my entire life to do it. I’ve worked on a lot of productions since then, and I’m now back to working with Dean on “The Librarians”.

Screen graphics for TV show “Powers”. Courtesy of Twisted Media.

Kirill: If you look back at 2007 when you started working on “Leverage” and your work since then, do you see any big changes in what productions expect from what you do?

Derek: It depends on what kind of a show it is. If it’s a show that takes place today, there’s been such a huge shift in our everyday lives. You look around, and no matter where you are, people are looking at their devices. So for these shows, art is imitating life.

There’s an interesting difference between the shows back then and the shows that are made now. A lot of these shows deal with the world of social media, where you can track somebody’s activity based on what they posted on Facebook. These things are mature and established, so there’s not much creative design or inventing how it looks. There’s still work to be done, but it’s such a mature playground now.

Everyone sort of knows what it looks like. We know the interfaces of Facebook and Instagram and Twitter. They are well-established. You are asked to show a character being on a social media, but it can’t be the actual thing. It is limiting, because we all know how that “looks like”. It’s not reinventing the wheel, but rather coming up with a creative way to do it. And oftentimes it looks a little weird. It’s just text on the white background [laughs].

We grew up with this in the last decade or so. This affects everyone’s lives. Consequently, when you design for it, you can’t take the viewer out of the moment and you have to take those well-established elements. You have to work with the parameters of what has come before and has been accepted.

Screen graphics for TV show “Scorpion”. Courtesy of Twisted Media.

Kirill: Is that due to production restrictions of not being able to use those branding elements without explicit permission from that company?

Derek: The clearance department is always the bane of our existence. They have to look at everything. You can’t use real usernames, for example. Everything that we make is fake. Oftentimes we call it Fakebook, because it can’t really be Facebook. We do work for “Empire” that has a lot of music gear. There’s a program that they use, and it looks a lot like ProTools, but it’s not. It’s FauxTools [laughs]. Everything has to be vetted. The design of it is copyrighted and owned property.

In a sense, working on something like “Independence Day” is so liberating. It’s not in a real world, and you can explore and make something, and it has nothing to do with today. You’re really creating a new world, and that’s where you can stretch your wings and do some neat stuff.

“Independence Day: Resurgence” alien biology research, head, interface. Courtesy of Twisted Media.

Continue reading »

Continuing the ongoing series of interviews with creative artists working on various aspects of movie and TV productions, it is my absolute delight to welcome Natasha Braier. In this interview we talk about the art and craft of cinematography, the hierarchical structure of feature film productions and how that structure still lends itself to predominantly male voices, and the pleasure and pain of working long hours over months at a time. The second half of the interview is on Natasha’s work on the meticulously crafted “The Neon Demon”, an engrossing story of a young girl taking her first steps as a fashion model in the wild urban jungle of Los Angeles.

Natasha Braier on the set of “The Neon Demon”. Courtesy of Natasha Braier.

Kirill: Please tell us about yourself and how you started in the field.

Natasha: I was doing still photography when I was a teenager. It was mostly black-and-white, developing them in my own dark room. The first time I looked at the end credits of a movie and saw the title of director of photography was when I was nineteen. I was immediately interested in that, and some of my older friends who I studied photography with had chosen to go to film school. It was through them that I discovered that world and the role of a cinematographer. That’s when I decided to go to film school myself.

Kirill: Do you remember being surprised at anything in particular when you started there, when you saw how things worked behind the camera?

Natasha: I wouldn’t say that I had big surprises. There were a lot of things to learn that were different from the world of still photography. If there’s anything that I didn’t know at the time I made the decision to go to the school and go down this career path, I’d say that I didn’t know that it would be such an intense commitment. You barely have time to have a life, and I didn’t know that I was going to spend so much time traveling and working away from home.

Also, I didn’t know that you could make so much money as a cinematographer. That was a nice surprise. I thought that I was going to be a humble artist doing what I love, much like other artists that I saw in my life. It was a good surprise that I get to travel the world and see all the exotic places, and make money. And the other surprise was that if you want to be home for a few months, that’s difficult.

Kirill: Looking back to when you were in school, what happened to people that went to that school with you? Are most of them still in the field, or do some leave it as years pass by?

Natasha: I went to a couple of film schools because I was moving with my family. I only stayed a few months in Argentina and another few months in Spain, and then I spent three years getting a master’s degree in cinematography in England. That’s the only education that I completed end to end.

That program was very selective, accepting only six people every year for each field. The other five that started studying cinematography with me that year were older than me, in their late twenties and thirties. Some had been camera assistants before, and they were really committed to this work. It was difficult to get into that school, and once you got in, you continued afterwards in the industry. Some had more success than others, but all of them are still working in the field.

Kirill: As you said, your job is quite intense, and you spend long months away from your family and friends, and long hours on set once the shooting starts. If we’re talking about you, what makes you stay in your field?

Natasha: It’s a great job and I love doing it. It comes with a cost, and otherwise it would have been a paradise. You pay a price. You have your freedom – you don’t go to the same job every day, you don’t have a boss, you get to choose your projects, you get to travel and meet different people. And the price you’re paying for that freedom and flexibility is that you don’t always know what you’re doing next month.

I think the world is divided into people that can live with that and people who need a stable life and a stable job. If you’re not the former, you will probably not stay in film industry. If you talk about people in the industry, we are not very normal [laughs]. We need the adrenaline and the highs. It’s like being on a rollercoaster. You have your ups and downs. That’s the challenging part of the work.

Over the years I’ve learned to deal with that in better ways, to not get so anxious about what I was going to do next, and to trust that there’s always something coming. I started enjoying the moments when I’m working a lot more, and to stop worrying about what’s next. It’s also a big spiritual test where you need to learn a lot about patience and not having control over what’s next.

Continue reading »

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()