Continuing the ongoing series of interviews on fantasy user interfaces, it gives me great pleasure to welcome Peter Eszenyi. Since joining Territory Studio in 2011, he has worked on movies such as “Zero Dark Thirty”, “Mission Impossible: Rogue Nation”, “Avengers: Age of Ultron”, “Guardians of the Galaxy” and “Ex Machina”. In the first part of the interview Peter talks about his earlier work on screen graphics for film, what makes for a compelling experience that supports the story and doesn’t distract the viewer’s eye, the unexpected facets of working in the movie industry and what people think when he talks about what he does for a living.

The second part of the interview focuses on Peter’s role as the creative lead for Territory’s work on the recently released “Ghost in the Shell”. We talk about abandoning the traditional rectangular flat screens, going into curved and holographic spaces, exploring a society that is embracing the potential of cybernetic implants and how that affects the interaction between humans and technology, the evolution of information presentation, and what the urban landscape depicted in the movie tells us about the technology of today.

Kirill: Please tell us about yourself and your path so far.

Kirill: Please tell us about yourself and your path so far.

Peter: My name is Peter Eszenyi. I was born in Budapest, Hungary, and that’s where I studied television and communication. I started to draw from a very early age, and after graduating, I started as an art director in advertising. I spent quite a few years in that field, working on various projects as creative lead.

As the advertising world was changing, and my real passion is design, I started doing freelance design and art direction work, and I was really keen to get into the 3D world. I was learning about various methods, workflows and software, and my take on that was always to use them as tools. The first package that I used in those early days was 3Ds Max, and from there I moved to LightWave and Cinema 4D. For me, it’s never been super important to stick with one tool – if there is something better or faster, I’d definitely want to use that.

I started to work with advertising agencies on 3D designs, concepts and motion graphics pieces, as the whole motion graphic world was really taking off then. And then around 10 years ago I started to work with agencies outside of Hungary – in places such as Germany and Scandinavia. As I started to travel more, I moved to London with my family. That’s where I got a phone call from David [Sheldon-Hicks], and in 2011 I joined the studio as Head of 3D. I’ve been at Territory since then – I’m basically the oldest employee here!

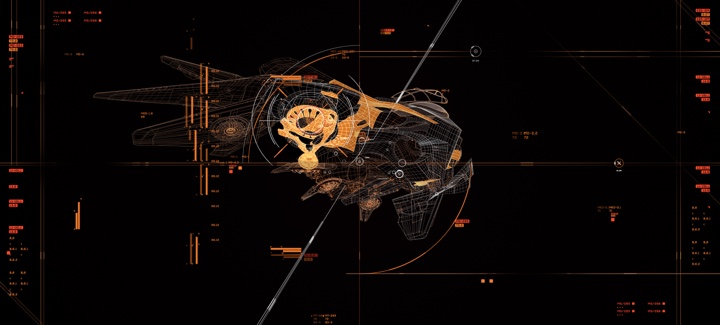

Screen graphics for Guardians of the Galaxy. Courtesy of Territory Studio

Kirill: Don’t say “the oldest”. Say “the most experienced”.

Peter: That’s true [laughs]. Territory has quite an extensive field of work, but my passion is mostly about films and telling the story to create something that supports the director’s vision. In the past couple of years it started to really happen here.

One of the things I’ve learned about my work is that content is always king. No matter how pretty it is, it needs to sell the thing. And it’s very similar in terms of film. No matter how pretty your UI design or hologram is, it needs to tell the story and support the vision that the director wants to see on the screen. I always try to keep that in mind, which is not easy.

Kirill: And you [motion graphics / vfx] usually don’t have a lot of screen time. Not only you’re “competing” against all the highly paid actors and actresses to get into the frame, but as a viewer I wouldn’t want to stare at some complicated screen while somebody explains exactly what each piece of that UI is for. There are the hero graphics that get a few seconds here and there, and then the rest of the screens are more or less part of the set decoration in the background such as on “The Martian”.

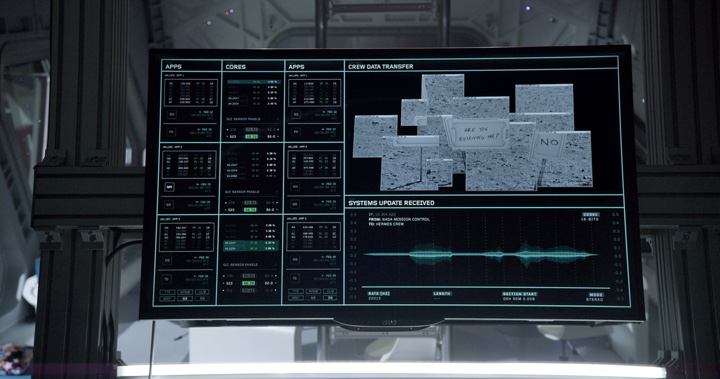

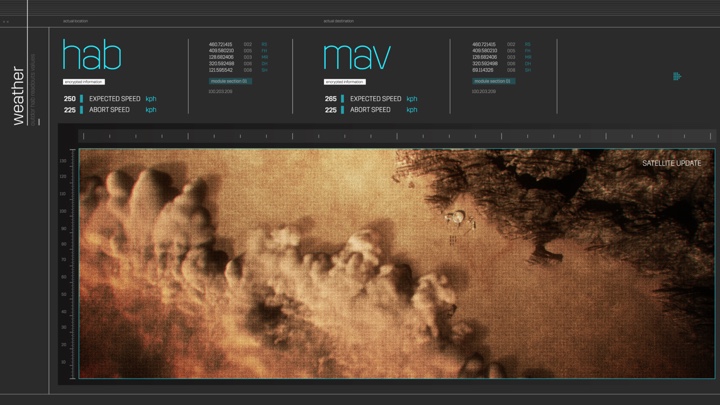

Peter: Marti Romances or David probably have told you this already, but we always try to design our screens to tell the story on its own. Even though most of the stuff that you see on “The Martian” is in the background and seems to be some random data, I’m absolutely sure that 99% of those screens are showing relevant stuff. If you look at the screens in HAB, that shows information on oxygen levels or timezones.

When we do screens at Territory, it’s very important for us to try and keep the “fluff effect” to a minimum – if it’s possible within the constraints. We do not have resources to do a thousand bespoke screens with a thousand pieces of bespoke data. But we try to avoid generating random numbers to put in the background, hoping that the camera is never going too close to that. We try to keep it real, as much as possible.

Screen graphics for The Martian. Courtesy of Territory Studio

That relates mostly to real-world stuff, and we can say that “The Martian” was real-world to a certain extent. However, on films like “Guardians of the Galaxy” or “Ghost in the Shell” you have a fantasy world. There we try to establish the world and the UI language in which the technology exists, and as part of that we define both the potential and limitations of what the technology can do. This process helps us create something that is credible within the context of that film and that story.

The successful examples of screen graphics that I see in film and television are those that, for me, have some sense of reality to them. I think that the viewer immediately recognizes when something is just numbers, or scrolls randomly in the background. I’m not saying that it doesn’t happen. It does, because of various factors. But let’s say you have a spaceship and a screen that shows speeds or distances. I want to try and keep those numbers within a fairly possible limit. That’s how I try to approach it. Maybe that’s not necessary, but I really like to think that most of the designers who work in film do the same.

Kirill: If I can bring you back to when you started at Territory on your first feature film production, is there any particular thing that you remember that was the most unexpected in what needs to be done for movie interfaces?

Peter: The first feature film that I worked on at Territory was “Zero Dark Thirty”. The designs that I did were intended to be utilitarian and reference military screens, and in that sense they were very pared back, minimal and constrained. It was challenging because we were trying to create an authentic version of something that most people, including us, knows nothing about. We researched what information was public, such as drone and satellite footage and military grade HUD and weapons references and designed drone screens and other military screens based on that information. I’m not saying that it was undesigned. We were just really strict with what we allowed ourselves to do on those screens.

“Fast & Furious 6” was my second film, and going back to your question, I was surprised by how most of the UI screen concepts were grid-based – heavily structured, sticking to certain predesigned grids and ideas. I always tried to bring a little bit more free-flowing stuff into my work, so this was an interesting contrast. David, Marti and others were doing strict grid-based designs, and I was fascinated by that.

I never worked with that rigid aesthetic before, and I realised that it was very important to learn. What I’ve learned in the last couple of years is that no matter what you think is a good style, you have to learn all the techniques and have all the tools. Most UI was grid-based for quite a while, and that was the biggest difference in approach for me as a designer. I come from a more traditional background, and I love the broad strokes of the paint brush. But when you design UI, especially for sci-fi and fantasy, you need to be very strict. Quite often, that’s what the story, the aesthetic and the production designer need.

Screen graphics for The Martian. Courtesy of Territory Studio

Kirill: Perhaps on both “The Martian” and “Avengers”, and to a lesser extent on “Guardians of the Galaxy”, you do have a military-style organization that imposes the formality of the structure on all those screens. And on your side, a modular structure would let you define templates and then populate dozens and dozens of screens in a more rapid fashion. So that’s a win-win where the production gets the right ambience of consistency and you don’t need to work on each screen as a separate entity.

Peter: It’s a bit of a chicken-and-egg – which comes first? Is it creating a library of widgets that you can shuffle around, or does it come from the other side? I’m fascinated by the amount of care and sheer work that Marti, David, Nik and Ryan and the fabulous designers put into it.

When I work with them, I try to be the person that does the free-flowing stuff. If I design a widget, or a hero 3D asset that is going to be featured, I try to be the one that breaks the rules – which is a nice contrast. But as you said, it’s an absolute must that you establish a structure that you can use to your advantage to churn out an insane amount of screens with a consistent look and feel.

It’s a good observation that some of the grid-based designs are dictating a more widget-based approach. It’s a shortcut, if you will, to designing a huge amount of stuff.

Screen graphics for Guardians of the Galaxy. Courtesy of Territory Studio

Continue reading »

Continuing the ongoing series of interviews with creative artists working on various aspects of movie and TV productions, it is my delight to welcome Derek Spears. Since joining the Rhythm & Hues Studios about fifteen years ago, Derek has worked on feature films such as “Red Riding Hood”, “The Mummy: Tomb of the Dragon Emperor,” “Superman Returns” and “X-Men: Days Of Future Past”. Most recently, his work as the Visual Effects Supervisor on HBO’s magnificent “Game of Thrones” has won back-to-back Emmy awards for Outstanding Visual Effects.

In this interview Derek talks about the early days of digital visual effects [VFX] and the evolution of the tools since then, the human-intensive parts of the VFX pipeline and his thoughts on what may happen in those areas in the next few years, the discussions that take place between the art department and the VFX department on building things physically, digitally or as hybrid, and the never-ending quest to take the audience on a wild ride of visual storytelling magic. The second part of the interview is all about the last two seasons of “Game of Thrones”, from creating the fire-breathing dragons to meticulously crafting the more “invisible” parts of Westeros and Essos, such as crowds and digital buildings.

Kirill: Please tell us about yourself and how you started in the field.

Kirill: Please tell us about yourself and how you started in the field.

Derek: My background is in software engineering. I worked at Silicon Graphics for a few years in the apps development group. During my time there I worked with Kodak to help develop their compositing system, and after that I joined Cinesite to help them start their 3D graphics department. After that I worked at Digital Domain, and now I am a Visual Effects Supervisor at Rhythm & Hues on features and episodic shows. There I’ve worked on “Game of Thrones”, “Black Sails” and “Walking Dead” in the episodic world, and on features such as “R.I.P.D.”, “The Mummy: Tomb of the Dragon Emperor,” “Superman Returns” and others.

My background is in computer graphics and the technology world, but I’ve always enjoyed the intersection of art and technology that visual effects has provided.

Kirill: Would it be correct to say that you’ve joined the field when digital was starting, and there were a lot of special effects with animatronics and other physical approaches?

Derek: Digital was still in its ascendancy back then. People were still trying to understand how it worked. It was very much the Wild West, the frontier type of landscape at that point in time. There were no well-developed ideas that we have now, like pipelines, render cues and various approaches and methodologies. We were learning at the time, and it was very interesting to be a part of that.

Kirill: Do you remember how it felt on your first few productions, as you “lifted the veil” and saw how the magic of movies looks like on the inside?

Derek: It was interesting to learn how a production was done. Coming from an engineering background, filmmaking was a new thing for me. The interesting thing about those early days was that every new show you got to, you had to sit down and decide how to do it. There was no well established methodology.

We didn’t typically use ray tracing. RenderMan was very popular at the time, and there were some other choices – such as Softimage and Mental Ray. The choices then tended to be non-homogenous. The options now are more developed, but also more similar in their approach to solve the problem. It was a bit more interesting in the early days. You had to get out there and figure out how to do things.

It was a much bigger chance of failure because it hadn’t been done before. Now if somebody asks you to do something, the chances are that you’ve done something similar to it, and that it’s going to fit into the existing pipeline. We have tools for various situations, and that is not true for the early days.

Kirill: Looking at the evolution of hardware and software at your disposal, would you say that they’ve kept up with demands from the production side to keep on increasing the level of sophistication of the worlds you’re building?

Derek: There are a couple of interesting things here. There’s always the attempt to decrease the amount of human labour in any given problem. Lighting is the one that has made the most advances out of the many disciplines. It used to be a very difficult and time-consuming problem. Now you can capture light on set and then quickly recreate a very close approximation of it in render without a lot of experimentation. You still have to do a lot of work for modeling and texturing as the setup, but the actual lighting process is rather quick.

Animation and motion capture has helped, but I don’t think that it has taken a lot of labour out of animation. There are tools that are better at rigging, but it’s still an extremely labour-intensive process. The same goes for compositing. There’s a much larger toolset to make things work a lot better in a lot more difficult situations, but what we find is that complexity of the problem matches the efficiency of the tools. For everything that gets faster, the complexity is increasing. It used to take 12 hours to render a chrome sphere and now it takes 12 hours to render a dragon. It’s the same time to render, but you get a lot more for it.

I don’t think that things ever get simpler. It’s rather that the available resources increase the complexity.

Progressive layers in VFX for “Game of Thrones” by Rhythm & Hues.

Kirill: Now that there’s so much being done in the digital pipeline of VFX, is there any friction between the art department that lives in the world of physical sets, and the VFX department that is creating all these fantastical sets in pixels?

Derek: In many ways, the art department and the VFX department are quite complimentary. What the art department designs, the VFX department has to realize. In some places we’ve seen crossovers, like on “Oblivion” where the art director came from the VFX background. I haven’t seen any tension between the two departments on the productions I’ve been involved with. It’s always very cooperative, to the point of how can we involve the art department to help design and solve some of the VFX problems.

In fact, it gets so close on some of the shows. On one of the shows that we’re working on right now, we’re acting as part of the art department to help design creatures. I view it as a synergistic relationship.

If you’re talking about trade-offs, one of the things that you have to figure out is that everything costs money to do. When you design a big set of platform for your show to work on, one of the things that the two departments have to work out is what is the most cost-effective way to do that. How much are we going to do practically? How much are we going to do in VFX? In no way is that a combative relationship. Together we figure out the best way to not break everybody’s budget. Usually that works very nicely.

Progressive layers in VFX for “Game of Thrones” by Rhythm & Hues.

Continue reading »

What happens with the raw footage captured by the camera lens after the last “Cut!” sounds off on the last day of shoot? It passes through a lot of hands and eyes until we get to see the final version on our screens. Post-production includes cutting and editing the shots, sound editing, dialogue replacement, foley effects, sound effects and soundtrack, just to name a few. Color grading is an integral part of the post-production process, and is mainly composed of two parts – color correction and artistic color effects.

This is where the shots of the same outside scene taken under different natural lighting conditions (sunny / cloudy) are made to look visually consistent as if they were shot as one flowing sequence. This is where the existing footage gets its colors shifted to change how the viewers will subconsciously interpret the mood of that scene. This is where the magic of visual story telling gets shaped to the final intent of the director.

Continuing the ongoing series of interviews with creative artists working on various aspects of movie and TV productions, it is my pleasure to welcome Norman Nisbet. In the last couple of decades he has worked on a wide variety of productions in film, television, documentaries, commercials and music videos. Do colors carry universal meaning across different cultures in our increasingly more connected world? How do you tackle the limitations of much smaller color spaces on screens? How much have the software tools have advanced in the last decade or so? What went into color grading the wonderful world of “The Neon Demon”? And much more importantly, will we ever agree on the right spelling of the word “colour”?

Kirill: How did you get into the field?

Norman: I stumbled onto it, really. At that time I didn’t even know colour grading existed as a field. I knew about editing but never thought of the colour grading part. I always thought that was for stills photography.

I was working for Multivisio Holdings – an audio-visual company in Jhb, South Africa, doing video productions for the car industry (helicopter shoots etc), as well as staging and engineering shows and car launches. It’s much like the show business and everything that comes with it. At some point the company bought the first component digital editing suite in the southern hemisphere and an URSA GOLD with a Pandora Pogle to go with. The American operators were great guys and they were eager to teach me.

I was in luck! I was editor’s assistant for 6 months then a Telecine assistant for 6 months. Then I had to choose as they were hiring, and I chose the film/colour grading world. I was always painting and drawing, spending school holidays at that company to mount slides from car shoots for multiple projector slide shows. I was always drawn not to photography specifically but image making, if I may call it that.

Norman Nisbet’s work on Mena Maria’s “F*#$ You”.

Kirill: What is color grading? What it is that a colorist does on a feature film or a TV show?

Norman: Colour grading is enhancing the raw image that was shot on film or digital media to present to an audience on different formats. It is the bridge between the camera and the screen. There is a technical translation aspect to it, as well as allowing for a creative side of the process. The cinematographer has a chance here to enhance the image for the audience to enjoy the intended vision of the film or program. Colour grading has replaced the ‘colour timing’ process that was previously done in a film laboratory.

The role of the colourist is to help enhance that image and to be the cinematographer’s ‘hands’ by understanding his vision and making sure the audience will see the program or film in the way the cinematographer intended it be viewed. The colourist has a responsibility to convey the cinematographer’s intent. Obviously we (colourists) give creative input and have the technical know-how to carry out this process.

Norman Nisbet’s work on Medina’s “We Survive”.

Kirill: How do you describe what you do to people outside of the industry?

Norman: I describe it as photoshopping a moving image. Or nowadays as a ‘filter’ applied in Instagram. I enhance images to portray a mood to help the story. I create warmth or cold. Animosity or sincerity. A menacing darkness or a pastel universe. I carry the viewer through the scenery in a subliminal manner. I invoke feelings as the viewer watches the images. There is always the technical side too: matching scenes and shots as they are shot at different times or different lighting. Even making day time look like night time.

Norman Nisbet’s work on Medina’s “We Survive”.

Kirill: Is there such a thing as a universal “dictionary” of meanings to color choices to convey mood and emotion?

Norman: There are, of course, studies which show how a human body reacts to certain colours. Red raises the heartbeat, blue is calming. Mental triggers such as green symbolises growth but green is also jealousy and envy. So these colours can be challenges or to use as tools. Are nights blue?

Kirill: What are your thoughts on a much smaller color space on screens compared to real life?

Norman: Human eyes and the messages relayed to the brain are amazing! The amount of colour balancing that goes on in a split second! Looking at a smaller screen limits this spectrum. You cannot perceive the range of blacks so the picture is always more contrasty. In real life there is no true black or white, there are too many reflections bouncing around. You can almost touch colour if you look properly.

Any screen cannot truly show real life and the smaller the screen, the more distant the viewer – so a more contrasty picture will engage the viewer’s interest. Image compositions are clearer too. I feel it’s a pity that cinemas are losing popularity to home viewing or even on-the-go streaming for commuters, even though it is very convenient. There is still something to be said for the ‘cinematic experience’ as in ‘in a cinema!’

Norman Nisbet’s work on Doctors Without Borders.

Continue reading »

Continuing the ongoing series of interviews with creative artists working on various aspects of movie and TV productions, it is my pleasure to welcome Shane Valentino. In the last fifteen-odd years he’s been working on a variety of productions in music videos, commercials, TV shows and feature film world. In this interview Shane talks about the differences and similarities between these fields for the art department, treating every production that does not happen in the present day as a period one, the art of conveying emotions and feelings in the visual medium of film, and the changes in the world of cinematic story telling on our screens.

The interview centers on two striking movies that Shane has worked on as the production designer in the last few years. The first is “Straight Outta Compton” that captures the formation and evolution of the music group “N.W.A.” and the effect it had on both the music industry in the late ’80s, as well as the American society at large. The second is the impeccable “Nocturnal Animals” that weaves three stories, three worlds and three visual universes in one.

Kirill: Please tell us about yourself and your path so far.

Kirill: Please tell us about yourself and your path so far.

Shane: I’ve been fascinated with cinema since I was a teenager. I started taking film criticism and film history courses in high school in Los Angeles. Our instructor, Jim Hosney, was teaching surveys of American and European cinema and that’s where I was exposed to the films of Jean-Luc Godard, Bernardo Bertolucci, Michelangelo Antonioni and others. Seeing those films, and being exposed to the themes that those filmmakers were exploring, made me even more interested in pursuing filmmaking as a career.

When I went to college, I wanted to study film as a fine art. I was looking for ways to express ideas and themes through non-commercial means. There’s a whole genre of avant-garde and experimental filmmaking and that’s where I got hooked. My mentor was a woman named Chick Strand who was pretty well-known in that world. Eventually, I went to the San Francisco Art Institute to get my MFA in experimental filmmaking. That program rounded out my education and exposed me to even more disciplines – photography, sculpture and painting.

I entered production design through a stroke of luck. I had a friend who was an artistic director on a TV show and she needed some help. I didn’t know much about what the art department did when I started working with her. But I was intrigued by the whole process and I’ve been working in the art department ever since.

Design boards for “Straight Outta Compton”. Courtesy of Shane Valentino.

Kirill: So your start was in the TV world.

Shane: Yes. It was with the Oxygen network started by Oprah Winfrey. They were doing a lot of TV shows and that’s how I got introduced to the role of the art department. My first extensive project was with Isaac Mizrahi’s show on that network.

Through TV, I started doing commercials. I was always interested in working on feature films too. Living in NYC after finishing my graduate degree in San Francisco, I was introduced to the independent New York film scene. I started on indie films with super small art departments and budgets under $1M. It was a fantastic learning experience to see the different parts of the art department coming together on a relatively tiny budget – props, set decoration, construction, etc. From there, I moved on to larger-budget film projects.

Design boards for “Straight Outta Compton”. Courtesy of Shane Valentino.

Kirill: You’ve been working on music videos, commercials, TV shows and feature films. How would you compare these fields as far as the size and pace of the art department?

Shane: It depends on the budget of the project. For example, the art department for a big commercial can match what happens on a feature film or a TV project in terms of size and pace. Between film and TV, it’s usually about the same in terms of the department heads and the general size. On commercials we don’t necessarily have a construction department because it’s often outsourced to a vendor who can build aspects of the sets. But you definitely have the set dressing department, the props department, and the art department on every commercial.

I find that the difference between film and TV is mostly about pace. The TV format requires that you finish an episode in 7-8 days. As a production designer, you have to think on your feet to make these tight deadlines. You have to make decisions about how something should look as expeditiously as possible. You also learn to find locations that can accommodate a team that needs to work very quickly.

Pace is one of the reasons why a lot of us like to work on films. It depends on the budget and the amount of prep time of course, but you often have more time to create a concept or a theme, and to work through how those ideas can be fully articulated. You’re given the time to think through all the different aspects.

Design boards for “Straight Outta Compton”. Courtesy of Shane Valentino.

Continue reading »

![]() Kirill: Please tell us about yourself and your path so far.

Kirill: Please tell us about yourself and your path so far.![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()