Continuing the ongoing series of interviews on fantasy user interfaces, it’s my pleasure to welcome Krista Lomax. In this interview she talks about the relationship between tools and ideas, the increased presence of screen graphics across all genres of movies and TV shows, working with limited color palettes, and the many hats she wears on her productions. We go back to Krista’s earlier work on “Stargate” and “Stargate: Atlantis”, and then step closer to her more recent productions such as “Dark Matter” and “Continuum”.

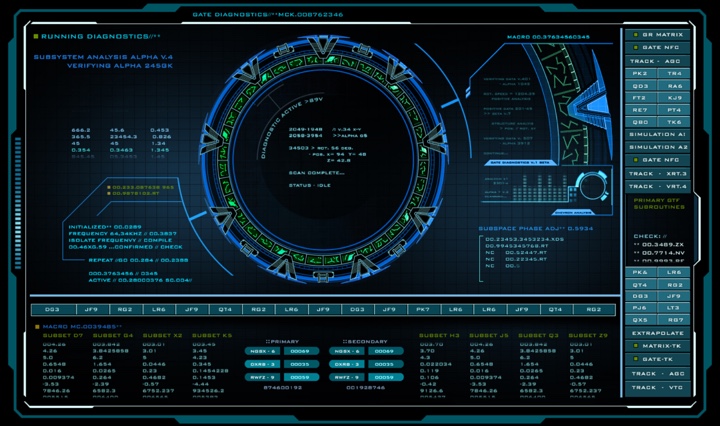

Screen graphics for “Stargate: Atlantis”, courtesy of Krista Lomax.

Kirill: Please tell us about yourself and your path so far.

Krista: I started way back with drawing and I was doing little videos and really lo-fi stuff using VHS cameras we rented from the gun & video store. Graphic design was a natural progression from there, and I started working for a film company that was creating tons of movies. They needed everything, and they threw me into creating visual effects with them. The next step was creating title sequences, and that’s how I got into animation with Premiere and After Effects.

Kirill: Looking back at that time with what you know today, what was the state of tools back then?

Kirill: Looking back at that time with what you know today, what was the state of tools back then?

Krista: I was mostly making stop-motion videos for animation. Ever since then I stuck with the basics, but definitely the technology today is amazing compared to what we had back then. You can make things look really gorgeous, and you can do it quick. It used to take two days to render something, and now two hours seems like a long time. It’s amazing what happened in just the last five years.

Kirill: Between the tools at your disposal and the ideas in your head, as a designer, do you think that one is more important than the other?

Krista: I don’t use tools to their extent. I mostly use the basics, because I like to keep things simple. This is why I like 2D animation. I like a more collage-y, scrapbook-y style.

Definitely there are two schools of people. The first is people who use the tools to get the ideas out of their head and onto the screen. And then there’s those who use the tools to create the ideas. Some people use every single tool they have, and everything looks flashy, and some people take simple ideas and use simple tools in more effective ways. I guess I’m less adventurous with filters and presets, I’m one of those for whom the ideas are more important.

Kirill: Without talking about specific productions, do you think there’s a certain overload recently in screen graphics that are a bit too flashy in how they use holograms, 3D and animations?

Krista: Some of them are over the top. I was reading an article that was showing before and after of some movie scenes. The before shows two actors and everything else is green screen. This is amazing, because it has its own audience and its own future. There are a lot of people who are sticking to the old-school way of doing it, kind of an indie, DIY look, but there’s definitely an explosion of CGI right now.

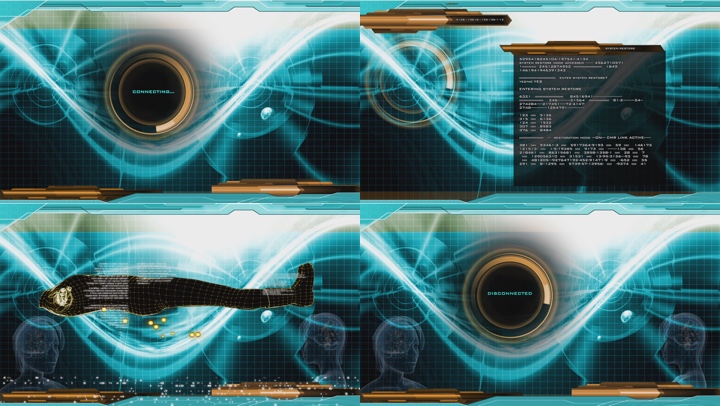

Screen graphics for “Continuum”, courtesy of Krista Lomax.

Kirill: Does it matter in the end as long as what we see on the screen looks believable in that universe? “Life of Pi” was an amazing visual journey ever though I knew that most of it was done in CGI. As long as the story doesn’t break the rules that it sets, then perhaps both approaches are equally valid.

Krista: I guess it’s like when the first cartoons were aired. The effect of intense realistic CGI is the same for this day and age. When people first saw a completely fictitious world created from scratch, they must have felt the same way as we do with the newest CGI. It’s suspension of disbelief either way, but it’s not taking over or ruining film or anything. Cartoons were always a fantasy world that kids loved, and we knew that it wasn’t real. These productions are just the evolution of those early cartoons.

Kirill: How did you get to doing screen graphics?

Krista: I was doing graphic design, and somebody called me to ask if I knew how to design playback. I said “Sure”, not really knowing what that was. He asked if I could design a radar screen. It was back around 2005, and I figured out how to do that in Flash. He loved it and brought me back to do a whole show. I did a lot of spaceship screens, and more calls came after that, and I ended up designing playback full time learning as I went.

Kirill: What was, or perhaps still is, the most surprising or unexpected part of your workday in this field?

Krista: Screen interface design is sort of a new industry, even though it is now in everything from romantic comedies to dramas. You have your phones, your tablets, your laptops. And the most surprising thing for me is how easy people think it is to create those screens. It blows my mind that you get requests hours before shooting for huge intricate things. It’s as if people think there is an “app for that” and you just press a button to make revisions. Some small changes take hours of work. And then there’s rendering time!

When I’m doing an episodic TV series, I’m there on set every day with new graphics. People have no idea how much time it takes to animate something, export the pieces, program them for playback, load them onto the machines and then test them. I do the whole process from script to playback, and I’m amazed that people think there’s an automatic button [laughs] that you just press to make these things happen.

It’s one of the most intensive things I’ve ever done. That is always shocking to me.

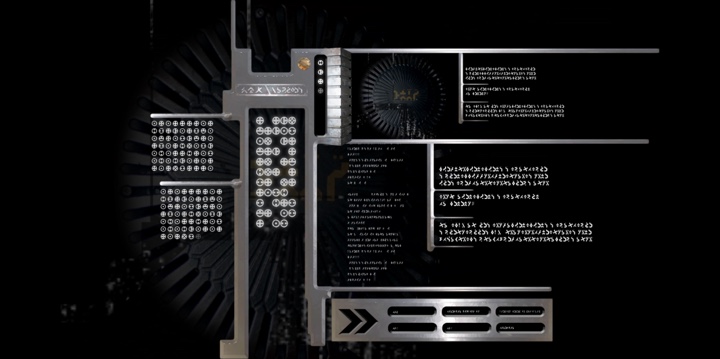

Screen graphics for “Dark Matter”, courtesy of Krista Lomax.

Kirill: Do you think it’s connected to how many screens we now have in our daily lives in the last few years? Perhaps people expect it to be easy because they are exposed to so much of it.

Krista: Absolutely. If there’s a problem with the playback, or if they want to change something on the fly, the first thing that people say is “But at home my phone / tablet does this when I press the button”. But what they don’t realize is that all of the interfaces are completely fictitious. They’ve been created from scratch, and they’ve been programmed to function in a scripted way.

It’s great that these interfaces are believable. But people on the set go “Well, just press that button” and I know that that button does nothing, because I did that whole interface. People are so used to interactive screens from ordering food to going to exhibitions. They are so used to interfaces being interactive and on-demand. They cannot comprehend the amount of time and pre-thought that has to go into any actions that need to be done in each interfaces.

Something may look similar to an Apple interface or to an Android interface, so they think that limitless options are available. But these are created on the daily basis for that one tiny specific piece of the script and don’t do anything else.

People expect everything to be fully functional. But these are different. These are pretend [laughs].

Kirill: Perhaps this is more relevant to the sci-fi genre, but I often find myself watching movies and shows to escape from reality for a few hours. So it would be pretty boring to see screens that are similar to what I have around me at home and at work. Do you find yourself competing against such contemporary interfaces, to make the story more interesting and compelling for the viewers?

Krista: Definitely, but that’s where we are lucky. We get to create things that look cool, but don’t actually have to be fully functional. That’s the fun part, to think about what would this character be using in a future universe. What would it look like? How would it function?

When I was working on Stargate Universe, they asked me to invent an interface that has never been seen before but would function in a new way if it did exist. They gave me two weeks to come up with it. So I flipped our usual interfaces inside out and rather than starting at one point and selecting larger and larger menus, I had every possible point accessible in a rotating sphere. That’s the fun – being able to invent something that has never been seen and think about how it would function differently from what we see in our daily lives. We are also cheating a tiny bit because we get to make cool-looking stuff that doesn’t have to have the back-end programming.

Screen graphics for “Stargate”, courtesy of Krista Lomax.

Continue reading »

Continuing the ongoing series of interviews with creative artists working on various aspects of movie and TV productions, it is my pleasure to welcome Elisabeth Williams. After doing art direction on the second season of “Fargo”, she continued into the third season as the show’s production designer. In this interview Elisabeth talks about her journey through the various roles in the art department, the arc of a production from initial explorations to watching sets being torn down at the end, the differences between the worlds of feature film and episodic productions, and working on the last two seasons of “Fargo” to build a unique universe for each.

Kirill: Please tell us about yourself and your path so far.

Elisabeth: I was born and raised in Montreal. My mother is French Canadian and my father was from Boston which has given me the advantage of being bilingual, and of having both Canadian and American citizenship.

I was on a very different career path when I started in film some twenty years ago. My upbringing had guided me towards academics, but while I was writing my Masters Thesis, the first opportunity to work as a Production Coordinator on a series arose. During that 18 month contract I fell in love with the process, and I decided that Production Design was what I wanted to do.

I did a three-month internship in the Art Department and then I hopscotched my way to where I wanted to be – over the next ten years – first as Art Department Coordinator, then as set dec buyer, set dec assistant and Set Decorator. Meanwhile, I had both my children and took night classes in Interior Design, and various drawing classes on the side. A producer I had been working for gave me my first break as Production Designer and, though I think hard work is the main reason for my advancement, a combination of fortuity and contacts helped get me to where I am today. I am indebted to those few people who took a chance on me over the years, and who gave me the platform from which to jump and spread my wings.

I did a three-month internship in the Art Department and then I hopscotched my way to where I wanted to be – over the next ten years – first as Art Department Coordinator, then as set dec buyer, set dec assistant and Set Decorator. Meanwhile, I had both my children and took night classes in Interior Design, and various drawing classes on the side. A producer I had been working for gave me my first break as Production Designer and, though I think hard work is the main reason for my advancement, a combination of fortuity and contacts helped get me to where I am today. I am indebted to those few people who took a chance on me over the years, and who gave me the platform from which to jump and spread my wings.

Leaving Montreal and my children to work on Fargo Season 2 in 2014 was a turning point in my career. There have been challenges and my children, their father and I have made sacrifices over the last four years. Thankfully, the support of my family has made it easier for us to handle those challenges and to live without regrets.

Kirill: When you meet somebody new at a party and they ask you what do you do for a living, what do you tell them?

Elisabeth: My first response is simply that i work in film, in the art department. I am never quite sure what people know about the work that goes on behind the scenes and I most often find myself having to explain the nature of my job.

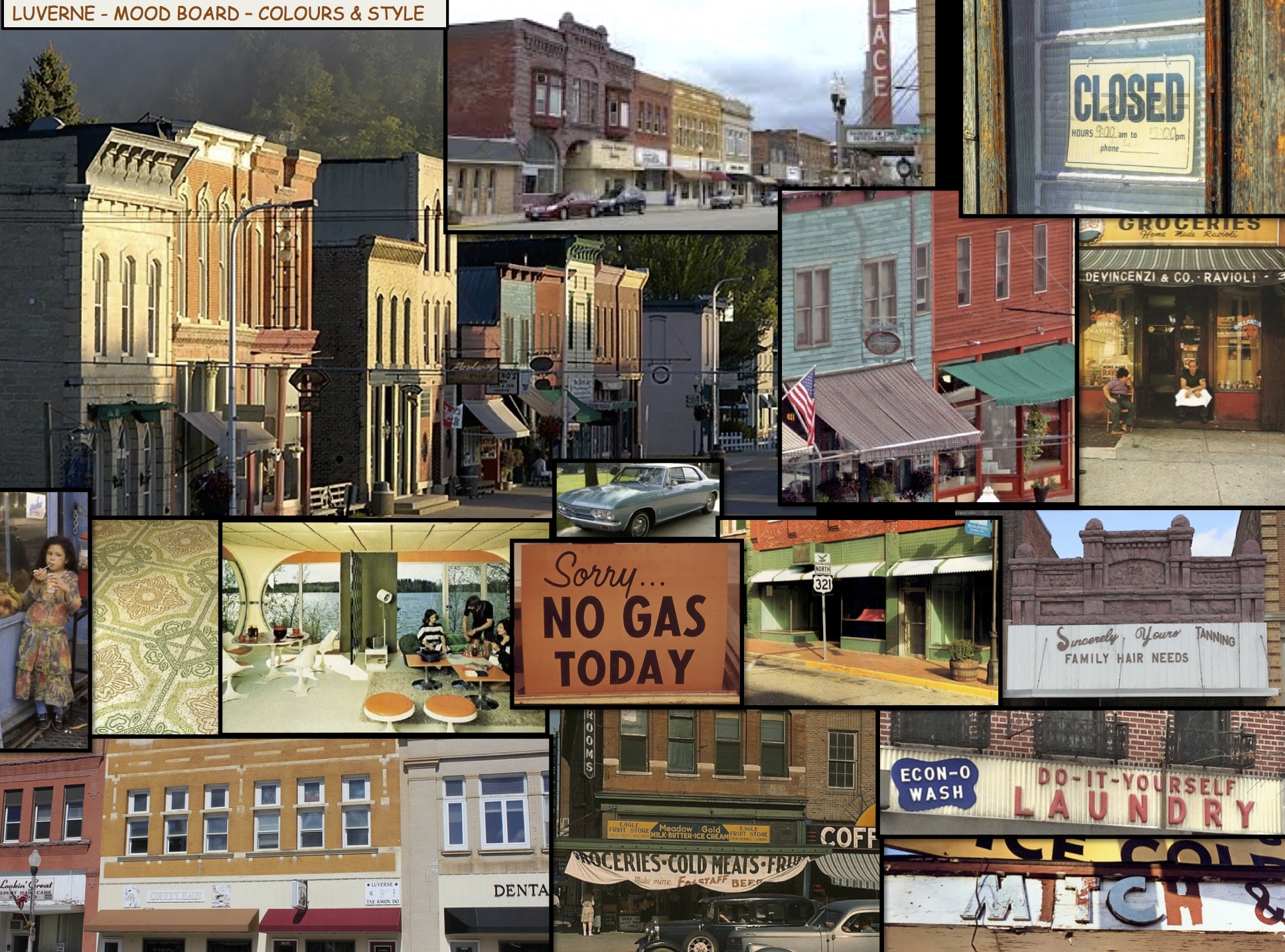

Moodboards for Fargo season 2, courtesy of Elisabeth Williams.

Kirill: Do you find that people are surprised that everything that is seen in films / TV shows has to be intentionally designed?

Elisabeth: Yes, I think that people don’t realize that each element is chosen to create a universe which complements, supports or enriches the story. In certain films and series it is obvious. The design stands out intentionally. The sets are a character in themselves. It is the case of “The Grand Budapest Hotel”, for example, or “The Handmaid’s Tale”. In a series like “Fargo”, however, though we treat the sets as characters in their own right, the design is more subtle because it purposely celebrates the bland.

Kirill: Going back to your first couple of productions, what was the most unexpected or surprising thing for you?

Elisabeth: The most surprising thing for me was the amount of work and collaboration goes into making films and series. It always feels to me like the project takes on a life of its own. It becomes ravenous and there are hundreds of us feeding it every step of the way and fighting to keep up with the way it grows and evolves.

Fargo season 2, courtesy of Elisabeth Williams.

Continue reading »

Continuing the ongoing series of interviews with creative artists working on various aspects of movie and TV productions, it is my honour to welcome Colin Watkinson. In this interview he talks about the evolution of the field of cinematography in the last couple of decades and how the transition to digital changed the dynamics on set, the role of the cinematographer, and telling stories with moving light. Around these topics and more, Colin dives deep into his work on the first season of the critically acclaimed “The Handmaid’s Tale” on which he shot all ten episodes, building the back story and the visual universe of Gilead.

Colin Watkinson and Tarsem on the sets of “Emerald City”. Courtesy of Colin Watkinson.

Kirill: Please tell us about yourself and your path so far.

Colin: I’ve been working in the film industry since 1989. I started in visual effects and then worked my way through the camera department – clapper loader, focus puller to the director of photography.

I was drawn to the camera department because it is so immediate to telling the story. I loved how they were right there at the forefront, and everyday they created something. Everyday you have something that you have made. I really like that. It’s different every day and I love that about it. Every day is a different challenge, different place, different people.

Kirill: When you refer to something that you make, do you refer to the physical medium of film that was on the set when you started?

Colin: I’ve done commercials, music videos, feature films and TV. On TV you have around four scenes to do every day, and at the end of the day you have four completed scenes. They will still go through the process of being edited, but it’s done. The same happens on commercials and other types of productions. You have something to look at at the end of every day.

Kirill: If you compare this to other art forms, like painting or sculpture, this medium is a bit more ephemeral or temporal. You have the physical medium of the disc for those that still buy them, but otherwise you can’t reach out and touch it. You can’t go around and look at it from a different angle. There is no physicality to it, so to speak. And there’s so much new stuff happening, that people rarely go back and rewatch it.

Colin: My work on commercials would be seen again and again and again. And I enjoyed making something that would be seen that way. You hope to strike a chord and make something that people will come back to and watch again, and they see something they didn’t see the first time – if it’s layered enough and complex enough to entice people to rewatch.

Now that I’m in the narrative world, I don’t have those feelings. But that was certainly true in the commercial world – to make something that resonated, something that could be watched again and again.

I’ve enjoyed the visual medium of the film from the very early age. And I never thought as an 18-year old kid in Liverpool that it was an option. At the time, there wasn’t an awful lot going on in the city. It was when I came to London that the option of working in this industry presented itself. With a little bit of luck, I took that chance and did it.

Then I started thinking what I would need to do to succeed in that industry. What talent do I have to work in this industry? I started working hard, and at some point I met Tarsem. He really spoke to me. Watching his work was interesting, and made me realize that I wanted to do what he was doing. I’ve been working with him since 1993, and he’s been a huge influence on my career.

We started out doing commercials, and his vision was outstanding and striking. That was what I wanted to do. I wanted to make images that would make people sit up.

Kirill: Looking back at when you started, do you think it’s easier to get into the industry these days? The equipment is so much more affordable, from cameras to even smartphones where you can shoot, edit and post your work without having to even buy a computer.

Colin: If you want to be a filmmaker today, it’s only your own laziness that will stop you. When I was 11 or 12, I couldn’t afford an 8mm camera, and it is just a memory. But for a young filmmaker these days, there is no excuse. There are so many tools. If you want to tell a visual story, you can tell it on your phone.

And because of that, the challenge is that much greater. There are a lot of people who want to do it and who think they can do it now. It is harder to rise above and have somebody pay you to do that. You can do it, but can you monetize it? Can you live as a professional? That’s probably the hardest challenge for people who are trying to break in today. It must seem like a glut of people, all trying to do the same thing.

Kirill: Would you say that the tools themselves play a much smaller part, and the main thing is how well you can tell that story, and perhaps a little bit of luck to get noticed?

Colin: There’s always an element of luck, and how you use that luck when it presents itself. It’s watching, learning and then doing. You don’t talk about it. You do it. You keep doing it. You keep making mistakes. Don’t be afraid to make mistakes. That’s part of the process – to learn what does and does not work.

Take as much as you can from everybody that you meet, and put that in your work.

Kirill: Do you miss the days of film as a medium? There was some magic to the cinematographer’s job to capture that moment through the lens while everybody else is waiting for the dailies to be processed.

Colin: I don’t. Technology drives us forward. You have to embrace it and accept it for what it is. You have to try to make your work better through it.

There were only very few people that could expose film in interesting ways, anyway. With digital, we can all be better cinematographers, because it is so immediate. We can make decisions and not worry about how it’s going to come out the next day. It’s right there for you to explore.

I really enjoy how immediate it is. You can be braver and bolder. There was a lot of safety in film. You go back to look at films that you thought were amazing, and it’s not quite amazing as what you remembered. There were, of course, masters that really knew what they were doing. But a lot of people just exposed it [laughs]. They told the story, but there was no bravery with the exposure, or the knowledge of what they were doing wasn’t as precise as the masters.

Continue reading »

Continue reading »

We are living in a time of unparalleled abundance of deep, thoughtful, provoking and captivating story telling in the medium of moving picture. Just a few short years ago, episodic television was the home for mostly generic, repetitive plot lines that you would occasionally dip into for a few episodes, soon to be forgotten among similar cookie-cutter stories. It was the world marked by long breaks inside each season, structured around “sweeps” rating peaks of November, February and May.

Things have changed dramatically in just the past few years, with tight and focused season arcs, entire seasons released for binge watching, delay-view technology that tipped the balance of when we watch our shows into our favor, and the undeniable tidal change in the entire landscape of how stories are told in the age of streaming. These days, I often find myself trying to fit “just one” more show into the few precious evening hours, answering the maddening question of what am I going to give up on watching this week.

“Black Mirror” is a show like no other. It’s an anthology set in a world just around the corner, a world that is at times soothingly tranquil, and at times achingly terrifying. It’s a world that shows the great promise of technology, and is not afraid to explore the dark corners of how that technology can undo the fabric of our daily social interactions at work, with friends and within family.

As the third season of the show wrapped up, I’ve had the honor of interviewing the production designer Joel Collins and the VFX director Dan May. The year before that I spoke with Gemma Kingsley on the screen graphics of the first two seasons, and last month I’ve had the opportunity to extend that discussion into the screens of the last two seasons so far with Simon Russell. And today it gives me great pleasure to welcome Erica McEwan who worked as the graphic art director on all 19 episodes of the show so far.

Branding for the UKN news channel that serves to move the plot forward, as well as to create temporal connection between different episodes. In top right, “Hated in the Nation” is connected to cookies introduced in “White Christmas” and Reputelligent company with word play on “Nosedive”. In bottom left, “Hated in the Nation” is connected to Shou Saito from “Playtest”.

Kirill: Please tell us about yourself and your path so far.

Erica: I was born in Canada, but I grew up on the sunny shores of Sydney. As a kid, I was often dragged into my dad’s office on the weekends. I was sitting there in his art department, playing with thousands of Pantone markers and thinking that when I grow up I want to color-in for a living.

I made it my prerogative to get into one of the university courses, to be visual, to do something with art. I did a bachelor of design degree in visual communication, focusing on film, video, typography and production design. I hated the computer. I hated technology. I wanted to do everything with my hands. When I finished my degree, I started working on a medical drama and some short films, starting at the bottom of the art department.

Soon I felt that I was suffocating in Sydney. I wanted to go where the lights were a bit brighter – to the US or Europe. I talked my way into a TV studio doing motion graphics and broadcast design, as the pay cheques were a little bigger, and within a year I found myself over in London knocking on doors and looking for a job in motion graphics. Ironically, I found myself quite a computer geek, living in AfterEffects.

Soon I felt that I was suffocating in Sydney. I wanted to go where the lights were a bit brighter – to the US or Europe. I talked my way into a TV studio doing motion graphics and broadcast design, as the pay cheques were a little bigger, and within a year I found myself over in London knocking on doors and looking for a job in motion graphics. Ironically, I found myself quite a computer geek, living in AfterEffects.

Through knocking on those doors I met Justin Chatburn who is a visual development artist now at Painting Practice. He gave me my first job in Soho. During the next six years I did a bunch of motion graphics jobs, especially title sequences for TV shows. I was still in the TV world, but it wasn’t quite where I imagined I would be. After those six years I wanted to be a storyteller again. I wanted to be a part of something that would let people escape for an hour and forget about their troubles.

Fortunately, in the meantime Justin had met Joel Collins and Dan May from Painting Practice, and he got me into their company for a few jobs. And before I knew it, I was talking with Joel about wanting to get back into the film world. He told me there was this crazy new show called “Black Mirror” that nobody knows about, but it has a lot of screens and graphics. He invited me to work with them, and the rest is history. Before we knew it, we were up to our eyeballs into season 1. It was complex, exciting and really hard work! The end result was so special and unique that we kept going back for more

Quite strangely, despite my early film and art department beginnings, it was my accidental foray into motion graphics for those years that actually paved my way back into the art department, to the role that I do these days – which is to create and art direct graphics on a physical and digital level, throughout the prep, shoot and post processes.

Once i got there, I fought the graphics thing for quite a while. I wanted to make stuff with my hands, and art direct in the more traditional sense. But when I realised there is such a need for graphics in so many formats, including physical elements that didn’t only exist in the computer – i began to really embrace the job. “Black Mirror” is such a complex job for graphics, so when Joel invited me to come and be part of the team I jumped head-first into that complexity. That’s how I ended up on this show.

Kirill: You mention that you’re working on both physical and digital level, and this is something that I also talked about with Joel and Dan – that Painting Practice chooses the best suited tool for the job, including some of the older techniques like matte paintings.

Erica: There are so many factors that come into why something would be done in-camera or CGI. On “Black Mirror” like on any other show, you ultimately have the constraints of time and money – so you always want to aim for the execution which will best visualise the story within those constraints – be it physical or digital. Some directors or actors prefer to have real, tangible elements there on the day, so we work hard to have that option. Personally, I feel doing as much as you can in-camera, especially up close gets the best results.

But sometimes you can’t find the exact location you need. Or you can’t shoot it wide enough and you have to extend that set. Or you have to realise an idea that is physically impossible to make, so CG is really helpful there. It is the marriage of the two – for the right reasons – that always gets the best results. And Painting Practice does that very well. They are able to cover both sides, physical and digital, and marry them in a way that you don’t know what was made on a computer and what was there in the beginning. It’s such an art.

From the graphics perspective, we might come up with a logo for a bank or need to build a gigantic sign, but the location would not allow safely hanging that sign on the front of the building. So even though we have created the design in the art department, we have no other choice but to comp that in in post. It’s a practical reason. The integrity of the design always remains. But what it comes down to a lot of times – is what you are physically able or allowed to do.

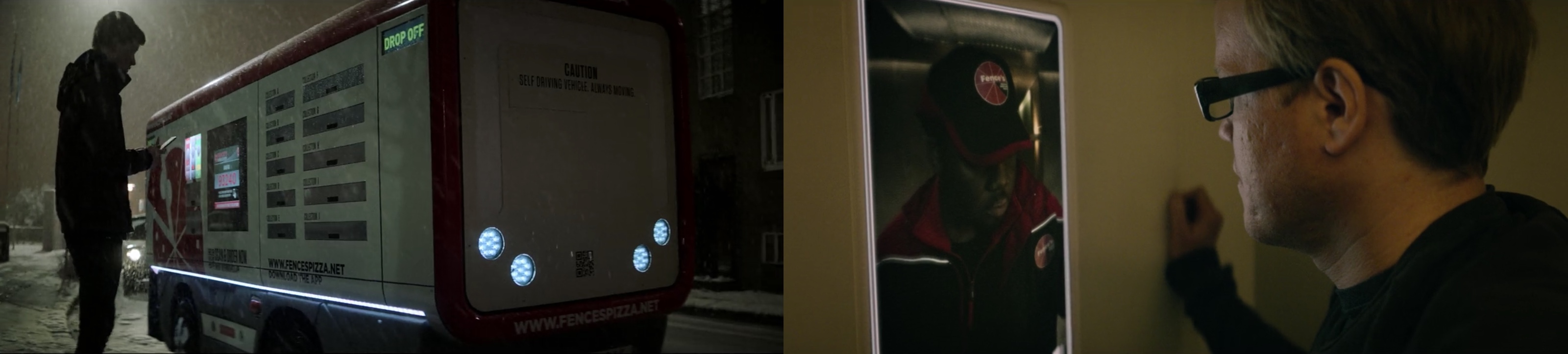

Fences Pizza truck from “Crocodile” and delivery person from “USS Callister”.

Kirill: Would you say that you build your sets for the camera? The set might not necessarily be a complete room when you’re in it physically, but as long as it is seen as a room by the camera, that may be enough. Is there some aspect of an illusion in those sets?

Erica: It depends on the story. If you’re talking about the white room in “White Christmas” or being a cookie inside your spouse’s mind in “Black Museum”, you want those worlds to transcend real or hypothetical spaces. You want those spaces to feel real enough that they are frightening, but illusion plays a part too.

Other times, you absolutely need to bring a sense of realness and reality to it. Take the spaceship in “USS Callister” as an example. It is a fantastical idea of course, but you want that spaceship to feel real. You want to be able to touch those screens and those controls. You want to feel that virtual space. That’s where VR is going these days. It’s so tactile that you feel that if you fall over, you’re going to hit the floor. It’s not an illusion, but rather a fantastical and tangible space to be in.

In terms of graphic design, I feel that you should do everything for the right reason and not just because you “can”. Just because we have great technological processes or the ability to do things that we couldn’t do 10 years ago, doesn’t mean that we should always choose those. We should do things with purpose and reason. To me, that’s good design.

Screen graphics for “USS Callister”.

Continue reading »

![]()

![]() Kirill: Looking back at that time with what you know today, what was the state of tools back then?

Kirill: Looking back at that time with what you know today, what was the state of tools back then?![]()

![]()

![]()