One of the most influential movies in my recent memory, “Her” explores the intersection of love, relationships and technology in a world where voice-based interactions and artificial intelligence have evolved to the point where they are virtually indistinguishable from those of humans. Credited as a graphical futurist designer, Geoff McFetridge designed the outer manifestation and the inner workings of that technology, balancing the dichotomy of how pervasive yet inconspicuous it appears to be.

We start the interview by talking about the role of design in our everyday lives, whether there’s such a thing as good and bad design, timelessness and fashion cycles in the world of design. Then Geoff dives deeper into the world of “Her”, from the directive to build a nice near-time future to crafting a narrative that reveals the quiet horror lurking beneath the utopian veneer of the characters’ lives, and working on the almost invisible interfaces of the technology that binds it all together. At it gets closer to the end, we discuss connections between the world that “Her” imagined in 2013 and the screen-filled obsession of our daily lives in 2018.

Kirill: Please tell us about yourself and your path in the world of design so far.

Geoff: I grew up in Calgary, Alberta Canada. I came to design through doing skateboard and snowboard graphics. Then I went to the Alberta College of Art and Design, and the program was very much rooted in what was, at the time, archaic techniques of design. That was around 1990 which was the beginning of desktop publishing, and computers arrived while I was studying there.

My work was street-culture related. I was doing skateboards and flyers, and working for people in California while I was in college. I figured that I wanted more out of design, and I applied to CalArts in California to their grad program. It was a deliberate turn for me, as I wanted to start from zero and really learn design. That was where I got my thinking. That program helped me develop my critical approach to design. It was within me, but I didn’t really know. It was a way of building a narrative into the work, but also being critical of your own work. Even before there were any client expectations, it was about meeting my own personal demands.

I’ve been in Los Angeles ever since. I’ve started my studio nearly right after I graduated in 1995. The plan was to have art shows, do animation and do design. These three things have been my pursuit since in different mediums.

My film work started in titles. I work with directors, and the only time I do that work is when I know the director and we have a working relationship, or I get called in to work on a project directly with the director.

Kirill: It feels like the past decade has placed a lot of emphasis on various parts of design in our lives. Instead of rushing to solve a problem, you have to understand it well enough so that your solution feels natural – which obviously takes a lot of work. Do you see that there’s more appreciation to the field of design in the last few years?

Geoff: Things have changed so dramatically. We live in a more visual culture. No longer is it shocking to be able to make a magazine on your desktop computer. You see both filmmakers and viewers that are so literate of design and culture in a way that I think is untapped. I always operate to design for people who are as literate or more literate in this world than I am. It might be doing a user interface or doing a logo for a fictitious company. People know the difference between a fake logo and a real logo when they see it.

When you see something like “Cyborg Incorporated” on a side of a bus in “Terminator”, it looks fake and people know that. Does that work for you? Does that help build that escape of being in a fantasy world? Or is it a flaw? That’s always been true. People are autonomous makers – in film, website design or other fields. That sophistication was there before, but it was untapped. But now people are also participants, producing so many things of their own.

Kirill: Is there a counter-edge to it? Anybody can be a producer, but also anybody can be a critic. There are so many social platforms and forums where people can easily critique design work without necessarily investing time to understand the limitations, constraints and thinking that surrounded that work.

Geoff: Absolutely. I’m not saying that design has gotten any better. There is more design. There is more of everything. But it’s not like we’ve entered the golden age where there is more beautiful stuff.

I always wonder what it would be like to live through the time of Art Deco. Would you be tired of all of it? Oh look, here comes the next toaster with lines on it. If I was alive back then as a fan of Art Deco, would I think that Adolf Loos is awesome, or would I be tired of it?

Nowadays there is a lot of critique. You can post something, and people link to it and link to other things. There’s a lot of connecting going on, and it is a type of a treadmill that doesn’t necessarily lead somewhere.

What’s the difference between an online forum and a critique in school? When you’re in grad school and you sit down for a critique, it’s powerful. That power is structured. There’s a culture of critique at the school you’re in. There’s someone leading it, and it looks very different from this commentary.

Continue reading »

5,736 pedestrians were killed in traffic crashes in USA in 2015. That is 15 people killed every day walking the roads.

37,461 people were killed in traffic crashes overall in USA in 2016. That is 102 people killed every day being on the roads. Additional (staggering) 2M+ were injured or permanently disabled.

There is nothing in the constitution, the bill of rights or the other amendments that guarantees an inalienable right for citizens, residents and other individuals to possess and operate a steel box at speeds that simply do not match our abilities to react in time to whatever may happen on the road at any given moment.

And yet, there is no public uproar. There are no petitions. There are no mass walkouts. There are no social media hashtags. There are no somber politicians sending thoughts and prayers. There is no government agency combing the aftermath of every single crash that resulted in a fatality to make sure that something like that won’t ever happen again.

Nobody gets in the car weighing their chances and deciding that yes, that trip to see their favorite team playing some other team is certainly worth the chance to die today.

Imagine getting on the plane knowing that there’s a decent chance that you’re not going to make it to your destination. Imagine a passenger plane crash happening every four days. Taking 400 lives. Twice a week or so. Because that is what is happening on the roads in this country. And every other country. More than 1.25 million people die every year world wide as a result of road traffic crashes.

And yet, there is no anger towards some kind of an organization that promotes the interests of big car manufacturers. Nobody is thinking to ostracize their friends for buying that shiny new car that can accelerate from 0 to 100 faster than ever before. There are no voices calling to raise the minimum driving age for bigger SUVs to, let’s say 21.

And here is where it gets really difficult. If self-driving / majorly-assisted technology could bring those numbers down, but not quite to zero, what would be deemed acceptable? Setting aside the juicy lawsuit targets and the initial wave of breathless headlines and rhetoric of the last few days, how little is still too much?

What happens when it’s no longer the weak excuse of “it’s fine because it was this frail human who lost their concentration for a second”? What happens when we are talking about machines of unimaginable complexity hurtling ever faster down our roads, as they take human lives on the monthly, weekly, daily or even hourly basis?

The advocates of fully self-driving future seem to never quite talk about this, pretending that somehow everything is going to be peachy and there are not going to be any human lives lost from some point going forward into eternity. This week is a rude wake-up call to regroup and start thinking about this ugly side of mass ground transportation.

The universe of “Black Mirror” continues to expand with each new episode, adding more layers and nuance to how technology of today can evolve in the near future. From the very beginning, the show was focusing much less on the technology itself, but rather on how it can change the fabric of our everyday interactions from the micro level of a single individual to the macro level of the society at large. And yet, the presence of technology in the universe of “Black Mirror” can not be denied, even through the most fleeting glimpses at the outer manifestation of that technology – glass surfaces, or screens.

Continuing the ongoing series of interviews on fantasy user interfaces, it’s my pleasure to welcome Simon Russell. In this interview he talks about his work on audio geometry experimentation and music visualization for concert stages, the symbiotic relationship between tools and imagination, the difficulty of creating something truly new and the drive to best serve the storyline with screen graphics. In between and around, we talk about Simon’s work on the screens of “Black Mirror”, from the corporate technology of “Hated in the Nation” to the futuristic graphics in “USS Callister” to the soft round shape of the coaching device in “Hang the DJ”.

Screens of “USS Callister” episode of “Black Mirror”, season 4.

Kirill: Please tell us about yourself and your path so far.

Simon: I did a degree in visual communication and moving image design at Ravensbourne, and then started working in the motion graphics industry. My first job was at the Cartoon Network, doing lots of kids stuff. Then I did lots of shiny R&B adverts for a company that was in the music business and then for a startup that basically stopped quite quickly, I’ve been doing freelancing in the last eight years or so.

My direction changed somewhat when I started 3D. I found it stimulating and challenging in a way I hadn’t found 2D work. Then I began to bring particles particles and simulations into the work and something really clicked. And that’s where I’m sitting at the moment – somewhere in between VFX and motion graphics.

Recently I’ve been doing music visualizations for concerts and projection mapping, and that brings me back to my college days. I did projects on Kandinsky when I was 15, and I loved the idea of visualizing music even then. And now many years later I’m coming back to it. It’s oddly circular.

Kirill: It’s quite interesting to see the hardware advances in that area and how much they are enabling in the last decade or so. You go to a concert or watch award shows, and it’s amazing to see all those screens in different shapes and sizes everywhere. And it didn’t even feel a gradual process. All of a sudden, these gigantic screens were everywhere.

Kirill: It’s quite interesting to see the hardware advances in that area and how much they are enabling in the last decade or so. You go to a concert or watch award shows, and it’s amazing to see all those screens in different shapes and sizes everywhere. And it didn’t even feel a gradual process. All of a sudden, these gigantic screens were everywhere.

Simon: I’ve been interested in music visualization for so long. I’ve went away from it and now I’m getting paid to do it on such a big scale. I did visuals for the Shawn Mendes world tour visuals, and the screens were insane. It’s the hardware and the playback that make it possible. It’s really exciting.

My motivation is to see it as pure experimental design. Everyone puts their own spin on it, and people see it on these futuristic screens. Aside from “Black Mirror” and live event work, I’ve been doing audio geometry experiments on my site. I’m getting some work from that, and it’s driving the jobs I’m doing. It’s nice and surprising that it’s working out like that [laughs]. It’s not often that things fall nicely into place like that. Maybe I’ve been doing it for so long that eventually it just clicks.

Kirill: We’re talking about number of screens, each with its own shape and size which is usually quite huge so that it can be seen from the back of that space. When you sit down to first think about it, what’s your approach to visualizing it? Do you do it on paper, or in some kind of a digital environment?

Simon: You start thinking about the idea, about what it is you’re trying to get across. For that, it doesn’t matter what is the shape of the box and how you are trying to draw it. It’s the same process. You get your concepts, you sketch, you make little experiments to prototype it in 3D. A screen is just a 2D surface, and it doesn’t take a huge leap of imagination to do it.

But the project I’m working on at the moment is this tunnel with 42 projectors super bright projectors. It’s going to be really long and really bright. And we’re using the whole tunnel, roof and all. The playout system we’re using can preview the setup in VR so you can really get a sense of the space and what you’ll be seeing. It’s amazing to see these particles waves flowing in time to the music, flowing down the tunnel. If it’s even close to that in real life it’ll be very powerful.

Visuals for Shawn Mendes Illuminate live tour, courtesy of Simon Russell.

I also worked with another client on a project where we visualise the space in Unreal engine to really get a sense of it. It can be used as a communication tool to show such spaces to clients, like film directors. Designers that work on more technical things know how it’s going to look and feel, but sometimes you need to lead people. So if you can put them into that world, it’s a very practical use of VR. Everyone is scrambling around VR at the moment, but nobody knows what it is going to end up being. I believe that this particular approach is going to be genuinely useful.

Kirill: Do tools matter as much as your imagination? The tools at your disposal continue evolving, but what good are those tools if, as a designer, you don’t have the right idea to work off of?

Simon: It’s a symbiotic relationship. It’s a fair point that you can have the highest-end computer, but it’s useless if you don’t know how to use it and you don’t have any imagination. On the other hand, you can have crazy ideas and no means to achieve them.

As ever, the truth is somewhere in the middle. This is where Painting Practice are so strong. They stand in the middle of that place. You have post-production houses which are very technical even when they have their design departments. But it’s hard to do simulations of what is physically plausible and still be loose and creative. You need to be in the brain-space to think about it in a purely creative way. It doesn’t always go hand-in-hand with those giant post places. This is where Painting Practice fits in. They lead conceptually, but also know how to follow it through and push those ideas down. It’s about defining those clear, beautiful, emotive ideas, about really creating a powerful concept but being able to lead that through all the hurdles and challenges of a huge technical production and still keep that original essence.

Visuals for Shawn Mendes Illuminate live tour, courtesy of Simon Russell.

Continue reading »

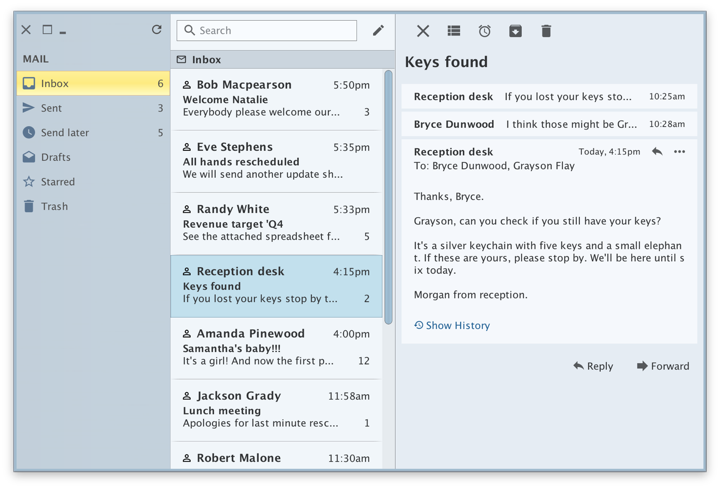

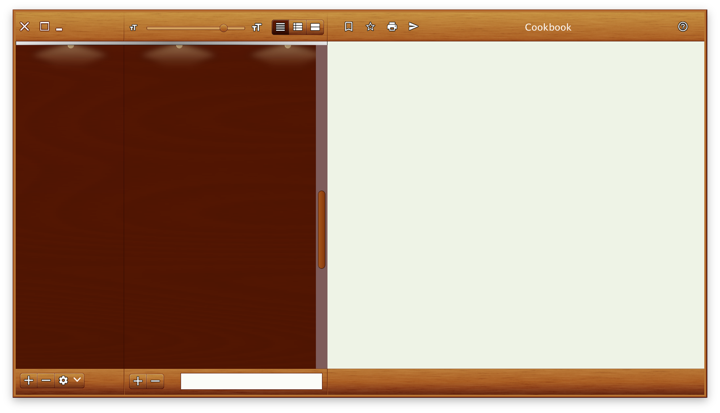

Going with the biannual release cycle of my Swing projects, it’s time to do latest release batch.

Substance 8.0 (code-named Wyoming) is a major release that addresses technical debt accumulated in the API surface over the years and takes a major step towards enabling modern UI customizations for Swing applications. Full release notes and API listings are available, with the highlights being:

- Unified API surface (Project Cerebrum)

- Configurable title pane content (Project Visor)

- Folded laf-plugin / laf-widget (Project Corpora)

- Explicit instantiation of component and skin plugins

- Switch to Material icons + icon pack support

- Better support for fractional scaling factors

Flamingo 5.3 (code-named Liadan) has extracted the non-core functionality into two new projects:

- Ibis has the code for using vector-based icons in Swing apps. It supports offline transcoding of SVG content into Java2D-powered classes, as well as dynamic display of SVG content at runtime (powered by the latest version of Apache Batik)

- Spoonbill has the code for browsing SVN repositories with the

JBreadcrumbBar component from the core Flamingo project. Future plans include extending this functionality to GitHub repositories as well.

If you’re in the business of writing Swing desktop applications, I’d love for you to take the latest releases of Substance and Flamingo for a spin. You can find the downloads in the /drop folders of the matching Github repositories. All of them require Java 8 to build and run.

![]()

![]()

![]()