Continuing the ongoing series of interviews with creative artists working on various aspects of movie and TV productions, it is my pleasure to welcome Ben Kutchins. In this interview he talks about his early experiments with film and the influence of that phase on his work, the importance of learning from mistakes, hiding the technical complexity around the shots and making them look effortless, and the transition of the industry from film to digital. Around these topics and more, Ben dives deep into his work on the first season of the critically acclaimed “Ozark” on which he shot six of the ten episodes.

Kirill: Please tell us about yourself and your path so far.

Ben: When I was 12, I found my dad’s old 35mm camera buried in a drawer collecting dust. There was a drug store near my house that sold film and processing, so I started taking pictures of my friends. I became more and more interested in what the world looked like through a lens.

I took pictures all the way to the college, when I got a summer internship with Lucasfilm at Industrial Light & Magic, and that was the first time that I saw people making movies. Like for most people, it was a complete mystery what happened behind the curtain. When I saw the craftsmanship that goes behind making something, I was hooked.

I saw a cinematographer lighting a miniature set from Jumanji that was going to get blown up. He spent a whole day lighting a miniature that was going to be on screen for something like two seconds, and most of that time it would be exploding. But he was giving so much care to every flag placement and every detail of how it was lit. That fully captured my interest. It was at that moment, I thought to myself, “I want to do that.”

I worked at Lucasfilm for a few years. It started as the internship, and then they offered me a full time position in the still photography department. They had a full photo lab and I was given time and materials to experiment and learn about film. My background is in film and photochemical process, and Lucasfilm is where I started developing different looks, cross-processing, over-exposing, under-exposing, using different stocks to see how they reacted. It’s not something that I utilize today at the technical level, but it fully influences what I do creatively. Most of choices are made in a digital world, but the idea of strong color choices, strong grain and texture, creating a vibe or a mood comes from the photochemical process and that time of experimentation.

There came a point during my time at ILM that it became clear that if I stayed there, my job would end up being creating computer-generated graphic work. When Lucasfilm originally offered me the job, I had quit school. I knew that I didn’t want to spend my life at a computer, so I decided to go back to school and study filmmaking.

I transferred to NYU and it was an amazing experience. I shot around 60 films in two years. There were only about four or five students interested in cinematography, and the rest wanted to be directors. The four of us included Rachel Morrison who just shot “Black Panther” and Reed Morano who directed “The Handmaid’s Tale” and a handful of other productions. It was a great opportunity for us to be able to shoot all those films for all the people who wanted to be directors. It’s where I learned the basic language of filmmaking. The majority of those I did hand-holding the camera in one hand, sometimes a china ball lantern in the other, running around the streets of New York shooting.

I only learn by making mistakes, and it was a great opportunity to make lots of mistakes. Some of those “mistakes” I love and I use today, and some of those taught me lessons and I try to never repeat them [laughs].

Kirill: Was there ever any disappointment in those days to see those tricks that almost fool the viewers to believe into seeing something on the screen that is not there on the set?

Ben: I was fascinated by the extreme amount of hard work that it takes, and I was never obsessed with thinking that we were fooling the audience. I am fascinated today still, and I am always deeply engaged in the process. When you are right in the middle of a setup or a shot, and you are trying to figure out the brutal honesty of the story that you want to tell, everything else falls away.

That is the reason why I keep on coming back to filmmaking. It’s the reason why I will always love it. Everything else falls away and time doesn’t matter. There is no moment where I’m thinking about the external world or what I should have for breakfast tomorrow. So there is no moment where I feel that we are lying to people. The reality is that we are not lying. At that moment I am fully engaged in the story that I am trying to tell, and I am looking for the truth and honesty of that moment.

You can view it as a trick, or you can view it as my truth. What is my memory of when somebody really hurt my feelings? What is my memory of pure joy? What is my memory of someone being dishonest? What does that feel like, and how do I translate that onto the screen so that the viewer feels just a tiny bit of what I am feeling? If I can transmit just the tiniest bit of that feeling, then I’ve done my job. For me, it’s the search for the truth.

Kirill: Is there anything that still surprises you when you join a new production and start working on it?

Ben: One of the things that I love is that each production is its own living breathing entity. It’s always a collaboration of a large group of people. We rely on everybody to make this dream come true. Everybody needs to get things done, no matter which level of the production hierarchy they are on.

It’s an ever-changing group of people. It’s a new group of people that work and think differently. The pace is different, the aesthetic is different, and there’s a difference about what is important. The environment is ever-changing and you have to adapt. I can’t come in and force my will on a production. I have to be malleable. I have to adapt myself to the situation that presents itself.

Kirill: When you meet somebody new at a party and you talk about what you do for a living, do you think they realize how much goes into what you do?

Ben: When I talk about what I do, I think that they imagine me with the camera on my shoulder running around and pointing the camera at things. They might also think that we can shoot the whole movie in a few days, and they might not even understand why that is impossible.

People that know me, people that I have real relationships with, know how much I work and how hard that work is, even though they are not in my field. But I don’t think that there’s any way, until you’re there, to really understand what we are doing and why it takes so much time. Sometimes it’s mind-numbing to think about all the details that go into making a particular shot work. You can spend multiple days doing just one complicated shot. It would be two days rehearsing it and then one more whole day shooting it. I think that is really hard to comprehend.

People would probably just think that we’re lazy or stupid from the outside [laughs].

Continue reading »

Continuing the ongoing series of interviews on fantasy user interfaces, it’s my pleasure to welcome Guy Hancock. In this interview he talks about the work that goes into creating screen graphics, the qualities of a good design, working within an established visual vocabulary and learning from screens in our daily lives. In between and around, Guy talks about his work on “Spectre” and the recently released first season of “Altered Carbon”.

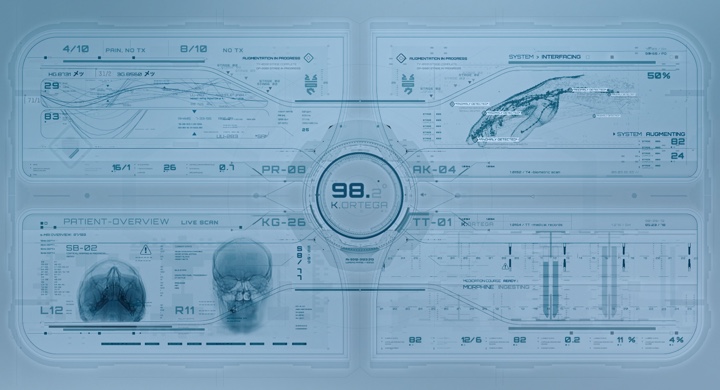

Screen graphics of “Altered Carbon”, courtesy of Rushes Creative.

Kirill: Please tell us about your path so far.

Guy: I kind of stumbled into design. I studied traditional film at a university, working a lot with 16mm and specialised in editing. After university I started looking for my first job in London, and got my foot in the door at Rushes which was predominantly a commercials post-production facility. I started as a runner and then moved to the machine room. That’s where I was introduced to the broad pipeline of visual effects (VFX).

We had copies of After Effects, Illustrator and Photoshop that we used to prep the artwork, I buried myself in these programs and I fell in love animating and creating graphics. I was given odd motion graphics jobs to do and regularly harassed the MGFX guys, eventually I merged into that team and I’ve been with them ever since. I was at Rushes for 10 years, and when they closed down the facility last December, the majority of the team moved up to DNEG to start their motion graphics department.

Kirill: Between the ideas in your head and the tools at your disposal to makes those ideas into reality, which side do you think is more important?

Kirill: Between the ideas in your head and the tools at your disposal to makes those ideas into reality, which side do you think is more important?

Guy: I don’t have a very traditional design background. I can’t even draw very well, and I much prefer to get in with the tools, start moving things about and take it from there.

Sometimes we’ll have an initial concept, and I’ll start to articulate that within the appropriate program and doodle from there. If it’s a screen interface, I’ll go into Illustrator and just start drawing shapes. That’s generally how I like to build up my designs.

Kirill: Would you say that with enough money one can do anything in these tools these days from the VFX perspective?

Guy: Technology advances so quickly in the VFX industry, both for hardware and software. Given an extensive budget, a lot of time and a lot of talent, we are at a stage now where you can create pretty much anything.

But a tool is still a tool. It comes down to the artists and how they can manipulate those tools. It’s about the skills, technique and the experience in using them. We’re a bit away from software doing it all for us. Who knows how it will be in the future, but for now you still need the talent to create those worlds. Technology helps us work faster, more efficiently and across large scale pipelines.

Kirill: How difficult is it to get across the complexity of what you do when people ask you what you do for a living? There’s so much design in our daily lives, and people probably take for granted that things just exist.

Guy: It’s a tricky one, especially when you’re talking about motion graphics. It’s such a wide umbrella term for so many things. You have screen interface design, title sequences, 3D, simulation, VR and so much more. It’s hard to explain what you do quickly.

I’m not sure the average person considers how much work is often involved in design. Unless you’ve involved in it, it’s hard to understand. You are literally building something from scratch. Of course, you have the software and plugins that help to fill it out, but you need to create it. We’re actually completely surrounded by design. You have hundreds of apps on your phone, expertly crafted for usability. I think that good design can be unappreciated and often taken for granted.

Screen graphics of “Altered Carbon”, courtesy of Rushes Creative.

Kirill: A seamless design that almost dissolves into its environment sometimes feels so effortless and natural. Should good design be in the business of drawing attention to itself?

Guy: It depends on what your product is. If you’re creating something user-friendly and it does its job, people probably are not going to notice it so much. Apple software, for example, is on the whole incredibly well-designed. To a lot of people that probably comes across as straightforward and clean, but the actual consideration behind it is extremely well thought-out and crafted.

I think that you might indeed overlook good design and take it for granted. It’s serving its purpose and doing its job. It’s easy to pick out information. It’s easy to move around it. It’s easy to understand. If it’s all of those things, it’s well-designed.

Kirill: Does it get easier to do what you do as you go from project to project?

Guy: The first thing that you need to consider on a new screen interface project is what is the purpose behind it. If it’s a hero screen, it’s going to be a part of the storytelling. How does it serve its purpose? How does it fit into the world that the director or the VFX team are trying to create?

Each time it’s a different challenge. A typical sci-fi interface might be more abstract and complex, whilst a contemporary film is likely to be more realistic and believable. Our work on “Spectre” for example had to be functional and convincing. The director didn’t want too much in there that didn’t serve a purpose. He would ask us to get rid of stuff that was unnecessary and just looked pretty. That’s a different challenge.

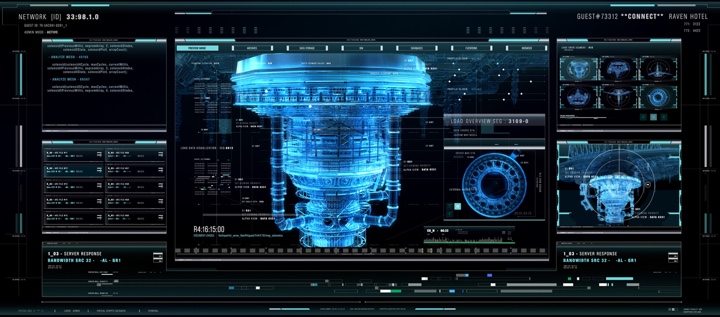

Screen graphics of “Spectre”, courtesy of Rushes Creative.

Continue reading »

Continuing the ongoing series of interviews on fantasy user interfaces, it’s my pleasure to welcome Serge Khomutovskiy. In this interview he talks about what drew him into the field, the relationship between tools and ideas, the crazy pace of work in the world of episodic television, and what goes into creating screen graphics that support the story. In between and around, Serge talks about his work on “Legends of Tomorrow”, “Arrow”, “The Flash”, “Supergirl” and “Wayward Pines”.

Kirill: Please tell us about yourself and your path so far.

Serge: Hi! My name is Serge and I am a creative designer based in Vancouver, BC. I graduated from Simon Fraser University’s School of Interactive Arts and Technology with a BA in Design and Media Arts. During my co-op placement the second Iron Man movie came out and inspired me to start an ambitious project that led me to where I am. I only had a basic knowledge about green screen and compositing from the few courses and videos I learned from. The project was to create a promotional video that showed a co-op student interacting with a virtual environment like menu that explored co-operative education options available to her. This project was a stepping stone to my career now as a motion designer and lead me to invest more time into learning and exploring the industry.

Kirill: What drew you into the field of motion and graphic design, and how did that change now that you do this for a living?

Serge: I’ve always been somewhat creative and originally wanted to get into print design or do some sort of graphic design. Growing up I read and watched a lot of sci-fi and was hugely inspired and enchanted by the worlds built in Neuromancer, Dune, Gundam, Star Wars and Star Trek, and a bunch of other less prominent franchises. Those stories will always have a special place in my heart and have definitely inspired me to explore and grow.

I was very fortunate and got to work with and learn from the amazing Robyn Haddow, Jeremy Unrau and Nick Oja at Scarab Digital. I have always been inspired by the works of Ash Thorp, Danny Yount, Corey Bramall, Jayse Hansen, to name a few. Direct exposure to motion graphics community was what drew me in. The openness, sharing of knowledge and support is what amazes me and keeps me going.

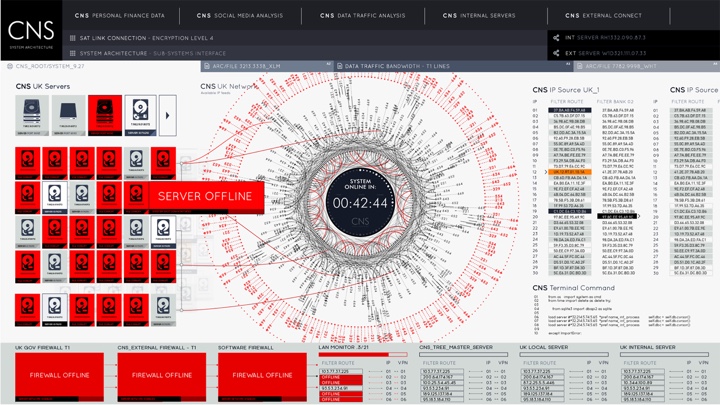

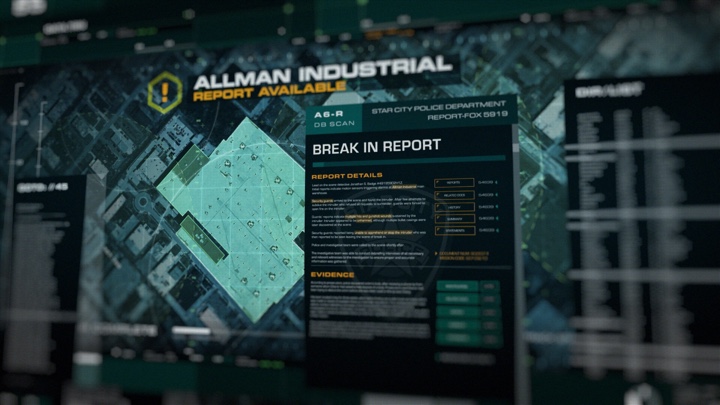

Screen graphics for “Arrow” season 4. Courtesy of Serge Khomutovskiy.

Kirill: Between the ideas in your head and the tools at your fingertips, do they have equal importance, or is one more important than the other?

Serge: Tools are important when you first start, but as you gain experience you build a library of various skills and techniques you can use that come naturally. Once those skills are developed and you have a workflow figured out, ideas become much more important.

Kirill: When you read a script and start thinking about the particular screens, do you go to pencil-and-paper, or straight to digital tools?

Serge: It largely depends on the scene, actor action and what’s been already built. Smaller background screens don’t require any interaction and are simply there for one reason, and that is to be a cool background. Those don’t require a lot of work and sometimes can be thrown together from previously created pieces. Most of the time it really helps to draw down a few things, sometimes a mind map, sometimes a diagram, to figure out what will actually be happening on the screen.

Screen graphics for “Arrow” season 5. Courtesy of Serge Khomutovskiy.

Kirill: What was, or perhaps still is, the most surprising or unexpected thing about doing screen graphics in episodic television?

Serge: Variety. I’m still surprised by the amount of variety that screen graphics can bring. Anything from your usual and very basic email and text editor to a complex schematic managing ion drive manifold (or something like that).

Kirill: What do you say when people ask what you do for a living? Are people surprised to hear that every single screen needs to be explicitly designed?

Serge: At the very basic level, “motion design and animation” usually gets the idea across. If I need to get into details then yeah, explaining that most if not all of the screens that people see in the scene are specifically designed, surprises a lot of people. It’s a simple thing that stays in the background and a lot of the time, out of focus, but every little detail contributes to the set and atmosphere.

Screen graphics for “Arrow” season 5. Courtesy of Serge Khomutovskiy.

Continue reading »

This week marks the beginning of a new phase for a bunch of my long-running open-source Swing projects. Some of them have started all the way back in 2005, and some have joined later on along the road. Over the years, they’ve been hosted on three sites (java.net, kenai.com and github.com) in three version control systems (cvs, svn, git). Approaching the 15th year mark (with a hiatus along the way), it’s clear that it’s time to revisit the fundamental structure of these projects and bring them into a more modern world.

This week marks the beginning of a new phase for a bunch of my long-running open-source Swing projects. Some of them have started all the way back in 2005, and some have joined later on along the road. Over the years, they’ve been hosted on three sites (java.net, kenai.com and github.com) in three version control systems (cvs, svn, git). Approaching the 15th year mark (with a hiatus along the way), it’s clear that it’s time to revisit the fundamental structure of these projects and bring them into a more modern world.

Since these projects have been brought back to life in the last two years, the entire codebase has been revisited to clean up the cruft that has accumulated over time. Some of the explorations that I’ve embarked on have not went as well as I hoped they would be. That has been the fate of laf-plugin and laf-widget projects that aimed to bring common functionality across a variety of third-party look-and-feels, a field that is only seeing Substance and Synthetica as the two lone survivors.

Today I’m happy to announce the beginning of Project Radiance, the new umbrella brand that will unify and streamline the way Swing developers can integrate my libraries into their projects. At a high-level:

- Radiance is a single project that provides a Gradle-based build that no longer relies on knowing exactly what to check out and where the dependent projects need to be located. It also uses proper third-party project dependencies to pull those at build time.

- Starting from the very first release (planned for second half of 2018), Radiance will provide Maven artifacts for all core libraries – Trident (animation), Substance (look-and-feel), Flamingo (components), Ibis (SVG icons) and others.

- The Kormorant sub-project is the first exploration into using Kotlin DSLs (domain-specific languages) for more declarative way of working with Swing UIs.

- Flamingo components will only support Substance look-and-feel, no longer doing awkward and unnecessary tricks to try and support core and other third-party look-and-feels.

All the open bugs on existing GitHub projects have been migrated to be under Radiance. Once the migration of all the relevant documentation and older binaries to Radiance is complete in the next couple of weeks, those projects will be deleted from GitHub.

Starting from today, all new development such as bug fixes, feature work and documentation updates will only be done under Radiance. The versioning of all the projects will be unified going forward, resetting to 1.0. Some public APIs might move between sub-projects (going into Neon).

![]()

![]()