Continuing the series of interviews with designers and artists that bring user interfaces and graphics to the big screens, it’s my pleasure to welcome Clayton McDermott. A multi-faceted portfolio highlights Clayton’s work in art direction, motion graphics, illustration and animation. He’s been with “Black Mirror” since the very first season when he worked on “Fifteen Million Merits” and “The Entire History of You”, as well as the now-iconic title sequence of the show. His work can also be seen in the later episodes such as “Men Against Fire”, “Hated in the Nation”, “Rachel, Jack and Ashley Too” and the most recent interactive installment of “Bandersnatch”.

Kirill: Please tell us about yourself and the path that took you to where you are today

Clayton: I never really knew what I wanted to do growing up, I was interested in a lot of things and I still am. I watched a lot of animation, I played a lot of computer games, I was amazed by film and animatronics, I drew, I painted and generally just enjoyed anything art and design related. I think more than anything though I was fascinated by how stuff worked.

I had a decent enough computer at the time and although the internet was still relatively young I began exploring some of the things that interested me digitally. I started messing around with programmes like Photoshop, Director, Adobe Flash, even HTML and began to realise I could use them to make my own content. It was around that time that I realised motion graphics was a thing and how a program called After Effects was being used to make some of the stuff I had seen on TV as well as things like DVD menus etc. All the while I was looking into these things I was learning and teaching myself new skills, I enjoy it all as a creative process. I began to realise that maybe if I just did something I enjoyed as a career hopefully it wouldn’t really feel like I was working. That’s where my career began.

Screen graphics for “Men Against Fire” episode of “Black Mirror”. Courtesy of Clayton McDermott.

Kirill: Looking back at your first couple of productions, what was the most unexpected part of working on client projects?

Clayton: I don’t think anything really prepares you for your first job and although I’m not sure it was completely unexpected I think early on in my career I learnt not to be too precious or protective about that initial idea. Things often evolve or change over the course of a project and more often than not you will need to revisit or adapt ideas as things progress. Sometimes a client brief will change so much you need to pretty much start again. There are often a lot of moving parts, it is what it is.

Kirill: Do you worry about how your work will age / be seen in 20-30 years?

I think it’s hard not to think about, especially when you have grown up and are working in a time that has seen such rapid advances in technology. Whether or not it worries me, I’m not so sure. I’d like to believe that everything has its place in time and I can live with that. I suppose most of the projects I have been involved with also serve as a form of entertainment and I’m still entertained by things that now might otherwise seem dated.

Kirill: Between ideas in your head and deep knowledge of tools to translate those ideas to the screen, what’s more important in your opinion?

Clayton: I suppose without the idea the tools are useless. When pitching ideas there are often parts where you are unsure of how you will achieve them. I guess that’s also what keeps me interested in the process – the idea of learning something new or going about solving that problem. It’s usually a good or unusual idea that forces me to learn more or develop that knowledge of those tools further.

Kirill: Looking back at when you started, do you think it’s easier to get in this field today compared to back then (better software, more affordable hardware, …)

Clayton: I remember when I started I just had to fiddle with the software to figure out what it could do and how it worked. Nowadays the internet is full of tutorials or information about how to create imagery using a wide variety of programs. Software has also just become much more accessible, I can’t remember the last time I saw or used a CD to install anything. I’m not sure laptops even come with drives anymore. With the advances in cloud-based software and subscription it’s easy just to rent software even if it’s just to try it. Obviously the internet has also been able to provide way more information than I could ever get my hands on when I started. Hardware nowadays pretty much comes right off the shelf as well, I remember a time when I had to order a computer to be built before I could use it. So I definitely think you have more exposure to the field than I ever had, not to mention an increase in available roles due to the development of film, tv and interactive content.

Screen graphics for “Men Against Fire” episode of “Black Mirror”. Courtesy of Clayton McDermott.

Continue reading »

Continuing the series of interviews with designers and artists that bring user interfaces and graphics to the big screens, it’s my pleasure to welcome back John Koltai. The first time we talked was six years ago, as he fielded questions about his work on “Iron Man 2”, “Iron Man 3”, “Robocop” and “The Avengers”. In this second installment John talks about his quest to improve his work-life balance, the meticulous attention to detail that goes into bringing these stories to our screens, the continuing prevalence of holographic elements in live action and animated features, and on finding the right color palettes for his characters. Between these and more, he dives deep into his work on “Spider-Man: Far From Home”, “Thor: Ragnarok” and the recently released “Spies in Disguise”.

Kirill: Since this is not the first time we’re talking, let’s dive right into it. What have you been up to professionally since the last time we talked?

John: Well, the biggest FUI project that I’ve done since we spoke has been “Spies In Disguise” from Blue Sky Studios.

That was pretty significant in that when I take an FUI project, I’m usually hired by a boutique design house that’s hired by the production company. But in this case, Blue Sky reached out to me directly and hired me to essentially be the design company for all of the FUI work.

A lot of times I work on very specific things, like one particular set of gadgets or holograms. There may be a ton of these types of elements in a film and it gets spread across multiple designers and animators. With “Spies in Disguise” I designed and animated every FUI element, so that was quite an undertaking and something I’m really proud of.

Outside of that you, I contributed some designs and animations to the latest Spider-man film, as well as “Thor Ragnarok”.

I do like to break things up and not always do UI design. So I’ve also worked in-house at Showtime branding their original show “Billions”, as well as doing a bunch of Showtime sports promos and designs. Another studio I love working with is Versus NYC, and I did a bunch of short fun explainer animations with them for the NFL on CBS. I also have some very talented friends that run a production company called Human Being and I partnered up with them on a number of their Governors Ball Music Festival recap videos, as well as some videos from the band Turkuaz.

Screen graphics for “Spies in Disguise“, courtesy of John Koltai.

Kirill: Does it leave you time to relax between productions?

John: I try to give myself some time between gigs. The last time we spoke, I was very much in a mindset of grinding and taking on everything. I had a tough time saying “No” to work, so I got a little bit burnt out.

I would say I’ve worked pretty hard on dialing in more of a proper work-life balance now. Right around the time of our last interview I learned how to surf, and that has become a huge part of my life. I feel that it balances the time in front of the box really well.

Kirill: Moving closer to these three features you’ve worked on recently, how does it feel to see months or even a couple of years of work condensed into a 90-120 minute final product? When you talk about what you do with people who are not in your field, how do you convey the complexity and the time scale of it?

John: Well in general I don’t think people outside of the industry really quite understand how much meticulous detail goes into making a movie. And that’s across the board, costume design, cinematography, lighting, script – all of it. I try to always display the work I’ve done on my website, whether it’s styleframes or a process reel, and I think that helps convey the complexity of what I do. And usually it’s the other creatives that understand just how long the time scale of these things are.

Screen graphics for “Spies in Disguise“, courtesy of John Koltai.

Continue reading »

Continuing the ongoing series of interviews with creative artists working on various aspects of movie and TV productions, it is my pleasure to welcome Brett Jutkiewicz. In this interview he talks about how he chooses the productions he works on, the role of the cinematographer and the hidden complexities of it, the dynamics of working on feature films with two directors, and the technological advancements in the lighting equipment in the last few years. Around these topics and more, Brett dives deep into his work on last summer’s delightfully wicked “Ready or Not”.

Kirill: Please tell us about yourself and the path that took you to where you are today.

Brett: I grew up in the suburbs of Long Island, about an hour outside of New York City. My father had a Hi8 camcorder that I would use to make little movies with my friends and as a teenager I started getting into skateboarding and making skate videos. I would always shoot them and edit them myself which at the time involved transferring it to VHS tapes, recording different parts of the tape onto another tape to make a really basic edit.

In high school I started getting into still photography. I did a lot of black and white photography – we had a darkroom in our high school and I took a photography class that made me think more about imagery in general, both as a method to capture and document things but also for the first time creating images that had a certain aesthetic value to them.

I went to college at Boston University and started as a computer science major because I thought it would be good for getting a job, but about a semester into that I became friends with some film students and realized this thing that I was passionate about in terms of photography and making videos could actually be something that I could do as a career so I took an elective film history course just to see what it was about and I completely fell in love with it and joined the film program.

I shot a lot of short films in school and after I graduated I moved to New York City with some of the people that were in my class at BU. I started working in New York and collaborating with them on shorts and became friends with other young filmmakers on the scene at the time. There was a great energy of people being creative and helping each other make films, and around that time the first DSLRs that could shoot high quality video came out, which opened up a new world for making cheap independent films. I shot my first feature about a year out of school, which was “The Pleasure of Being Robbed”, directed by Josh Safdie. It was this super scrappy film we shot on super-16mm with a crew of about 3 people, but it wound up premiering at Cannes and that was kind of the beginning of my professional filmmaking career.

Cinematography of “Lily” by Brett Jutkiewicz.

Kirill: Is there anything particularly surprising on unexpected for you when you join a new production, a new director, a new set of people?

Brett: There’s always something to learn, and that’s what’s special about filmmaking. No two productions are ever the same. There’s always a different challenge. A new person who comes in with a different vision. What is cool is that as a cinematographer I get to collaborate with all these different directors who have different styles and different visions.

After graduating from college I continued working with some of the same filmmakers I’d met there, so it wasn’t an abrupt transition. I worked as a production assistant a few times just out of college, and I remember being totally in awe of the machine of these bigger movies with $4-5M budgets, which at the time seemed enormous. It was interesting to see how complicated it was, how many pieces had to fit together, and how people kept things streamlined across different departments.

Kirill: There are different ways of telling the same story, in words and in images, and everybody has their own stylistic approach to it. When you are choosing your next production, do you want to be aligned on the sensibilities with your major collaborators? Do you want there to be a little bit of a tension in the process?

Brett: A little bit of tension and back-and-forth is good. Right after reading the script and before talking to the director, I always come in with my own ideas, a preliminary vision, and feelings about the script and how I might want to translate that visually. But the director might come in with different ideas and differing viewpoints, so I think you collaborate to distill the best of it, obviously always with deference to the director. I would expect always that there would be some sort of tension and back-and-forth. I think that’s why directors hire cinematographers – to bring their own vision and creativity to the project.

Some directors are a lot more precise about how they want the film to look than others. I’ve been pretty fortunate to work with a lot of directors who are very open to collaboration, and I think that collaboration is an important part of filmmaking in general. There are so many people that are working to create this apparently seamless vision. It’s important to have these different people who have different viewpoints to be able to bounce ideas off of each other.

And a lot of this happens in prep. By the time I get on set and am rolling the camera, it’s definitely important to be on the same page with the director. There’s so much to deal with. The director is dealing with the cast, the producers and the studio. I’m dealing with my crew, the camera and the lighting. It’s hard to take time and energy away from that to resolve any sort of tension or conflict. Obviously there’s a lot of adapting to different things that you haven’t planned for – but having that foundation in prep is really important.

Cinematography of “The Preppie Connection” by Brett Jutkiewicz.

Continue reading »

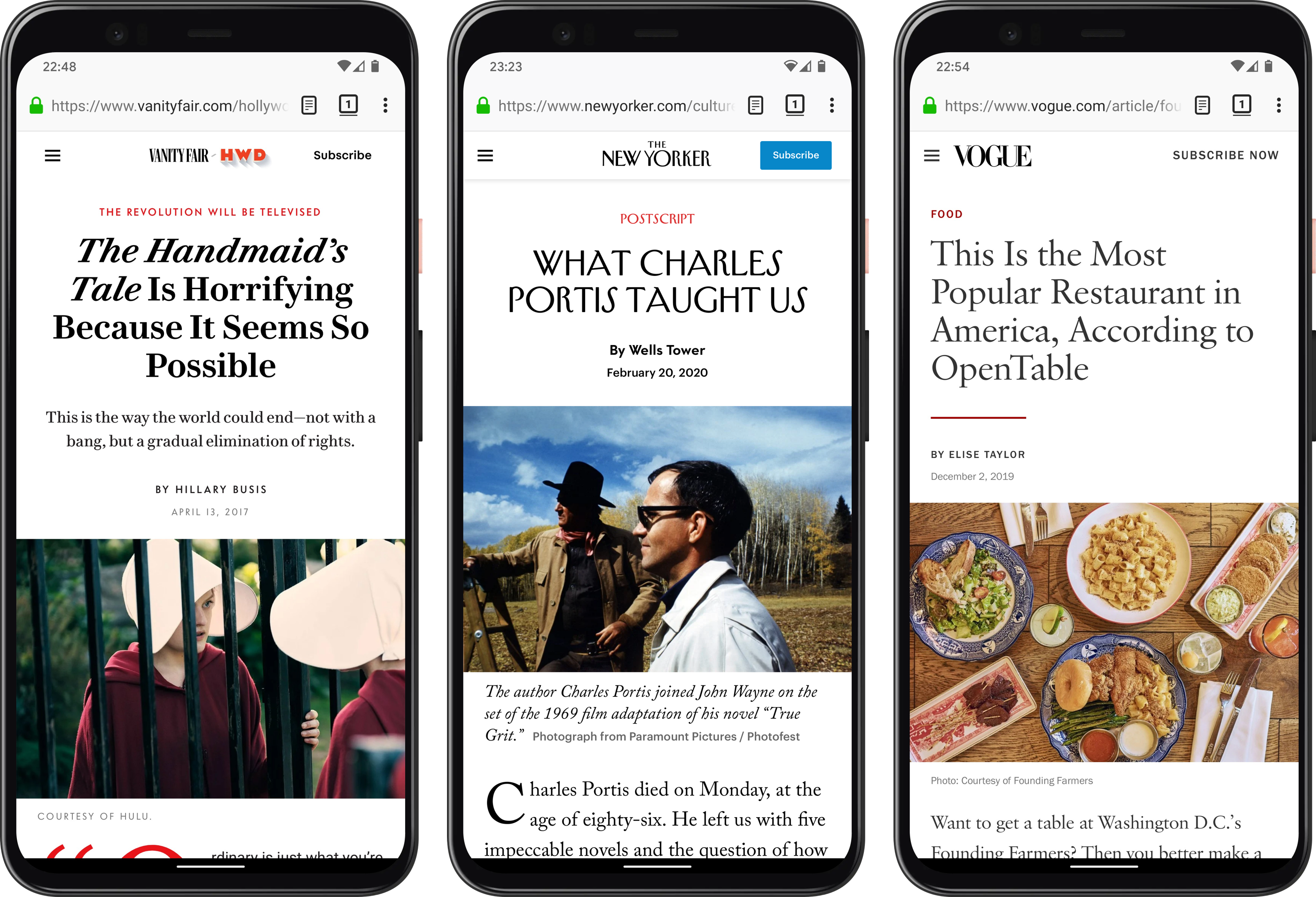

There are two things common between the websites in these screenshots that I took yesterday.

- They are beautifully designed, with great typography, clear branding, all optimized for readability.

- I had to install Firefox, Adblock Plus and uBlock Origin, as well as manually select and remove additional elements such as subscription overlays.

The web can be beautiful. Except it’s not right now.

![]()

![]()