“Moonrise Kingdom” is by far the most enchanting and charming movie that I saw in 2012. It is a great pleasure to have the opportunity to host Gerald Sullivan, the art director of this wonderful production, and to ask him a few questions about his craft, and his work on the movie.

Gerald Sullivan

Photography by

Niko Tavernise

Kirill: Tell us a little bit about yourself.

Gerald: I am a graduate of the Southern California Institute of Architecture, SCI-ARC. I began working as a set designer in ’95 without much prior knowledge of film making. Since then I’ve had the good fortune of working on a variety of films, gaining insight from many great production designers and working with some of the industries most highly regarded directors.

Kirill: In your experience, what’s the role of an art director in the overall production, and what skills do you bring to the table?

Gerald: An art director takes on many roles throughout the production. We need to be shape shifters. Initially we need to be able to conceptualize the scenery needed to tell a certain story. Budget and schedule need to be established. The art director has to be able to react, adjust and respond to inevitable changes through out each project. We are in constant contact with the assistant directors, the UPM [unit production manager], construction, set decoration, SPFX [special effects], the Director of Photography, the key gaffer, the key grip, etc. Every art director I know has an appreciation for art, architecture, decoration, and the history of each. The best understand we must be learning more all the time, constantly expanding our knowledge, what we bring to the table.

Kirill: From set decorator to art director to production designer. Is it a natural progression, or just one path to follow?

Gerald: No natural progression, no one path to follow. Doesn’t need be a progression that aims toward, or ends up at, production designer. Whatever your best at, and take pride in doing, that’s where you should be.

Kirill: How did you end up working on “Moonrise Kingdom”?

Gerald: I had worked with Adam Stockhausen on a film the previous summer in Michigan. We got along well. I am a big fan of Wes’s work. Adam had worked with Wes on “Darjeeling Express” and a few commercials as an art director. When Adam let me know he was going to work on “Moonrise” as production designer, I let him know I was interested in art directing.

On the set of Bishop family house. Photography by Niko Tavernise, courtesy of Gerald Sullivan.

Outside shot of Bishop family house. This extension was built to match the house and provide the director with what he needed for each scene. It also camouflaged a non-period sun room.

Continue reading »

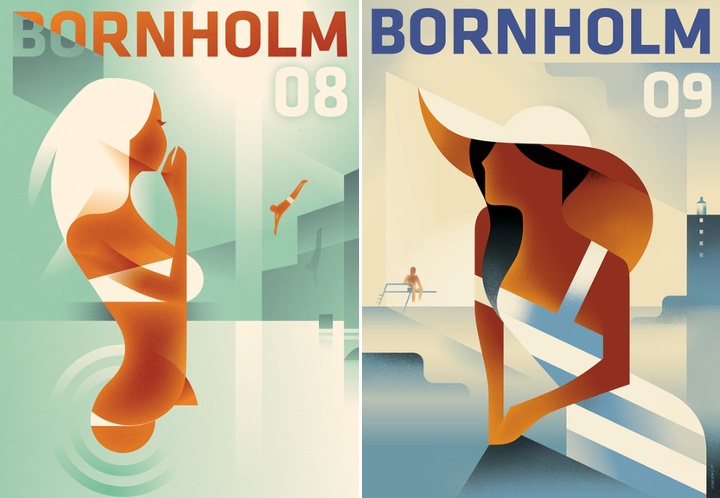

The work of Mads Berg is a perfect translation of classic poster art into the landscape of contemporary illustration. A flowing effortless interplay of shapes, colors and grainy gradients creates a unique and immediately recognizable style. Mads specializes in posters, editorials and brand illustrations, and his online portfolio is a veritable treasure trove. His art prints are available for sale at Arte Limited, and his extended portfolio is over at Behance. In addition, he’s part of a small team that creates maps for theme parks, amusement parks and zoos all over the world.

Today I am honored to have an opportunity to ask Mads a few questions about his craft.

Kirill: Your style is very unique and immediately recognizable. What are your influences?

Kirill: Your style is very unique and immediately recognizable. What are your influences?

Mads: A mixture of everything really. I like paintings, Italian baroque, Dutch renaissance, Danish Golden Age and of course Art nouveau, Art Deco and cubism.

Kirill: Do you see your style evolving? Is there ever a thought of exploring radically different directions? Is there a concern of falling into a certain rigidity of style?

Mads: Evolving my style is not only a popular demand but also an important way to challenge myself and to continue to be curious in what I do.

Kirill: Do you keep a sketchbook to develop ideas in between projects?

Mads: I often keep my sketches or prints of my visuals in progress in my pocket for days to view it once in a while, and to let it mature over time.

Brand illustration for Tuborg Classic. Courtesy of Mads Berg.

Kirill: Do you prefer getting a full artistic freedom for a project, or a more defined direction from the client?

Mads: I do not mind working from a well defined motive or scene, or even a product as long as I have the freedom executing it.

Kirill: Pen and paper, or digital? How has your choice of tools evolved since you’ve started in the field?

Mads: You cannot beat sketching with pencil or paper. But finalizing images on a computer is really wonderful excellent for exploring color tones and values.

Kirill: What’s the best thing about being an illustrator?

Mads: Vanity i believe. Turning a white nothing into something beautiful.

Kirill: Your final illustrations seem to be reduced to bare essentials. Do you remove clutter until there’s nothing left to remove?

Mads: I try to, yes.

Posters for the Danish Island Bornholm. Courtesy of Mads Berg.

Kirill: And on a related subject, the way you render human body is absolutely fantastic. Would it be wrong to say that it’s one of your favorite things to draw?

Mads: It is indeed one of my favorite things to draw. Apart from depiction of eyes, I think the human body has the strongest attraction in an image.

Park map for Legoland Florida. Courtesy of Mads Berg.

Kirill: You’re part of a small team that creates maps for theme and amusement parks. What is the process of creating a new map like?

Mads: Research and description of style and approach. It’s much about laying out pathways and supersizing the essential features and eliminating the less important ones.

Kirill: How do you bridge the gap between staying faithful to the park layout with abstracting away the unnecessary details? Or is there no gap at all and these are two sides of the same coin?

Mads: A lot of stretching and tweaking has to be made, but as long as the paths connect where they do in reality, quite some fantasy can be used.

Kirill: Do you spend time on personal projects, and how important is that for you?

Mads: I make 50 xmas cards every year by hand. That makes me happy, so that must be important.

Healthy community magazine cover. Courtesy of Mads Berg.

Kirill: Do you think that advances in software tools and global connectivity are making it simpler to start in your field, and at the same time creating more competition and diversity for the clients to choose from? Does it make harder to stand out?

Mads: Global connectivity yes, software no. True talent combined with consistent work always stands out, I believe.

Kirill: There’s a recent surge of interest in mid-century inspired illustration, photography, fashion and design. Do you see this as a younger “digital” generation trying to recreate the old “analogue” look and capture that spirit?

Mads: Yes, nostalgia and the search for authenticity is sign of the times. I think that knowledge and appreciation of visual heritage must be combined with fascination of the new. Past time heroes also copied their ideas.

Left – poster for Air Greenland, right – poster for Hansen’s ice cream. Courtesy of Mads Berg.

And here I’d like to thank Mads Berg for graciously agreeing to this interview. Selected prints available for sale at Arte Limited.

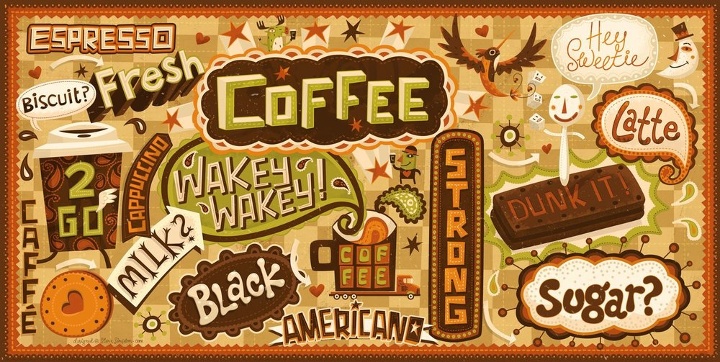

Steve Simpson‘s work spans editorial print illustration, packaging design, children’s books, postal stamps, album cover art and much more. His unique approach combines such unlikely elements as retro vintage colors, folk art references and mid-century cartoons, bringing them together in a vibrant and immediately recognizable style. His active digital presence includes his main portfolio site, as well as Behance and Twitter. Selected prints are available for sale at Society6 and The Copper House Gallery.

Today I am thrilled to have an opportunity to ask Steve a few questions about the art and craft of illustration in the digital era.

Kirill: Tell us a little bit about yourself and how you got started in the field.

Kirill: Tell us a little bit about yourself and how you got started in the field.

Steve: Originally from the UK, I’m an illustrator and designer now based in Dublin, Ireland. I’ve been working in the area of design for print for the last 20 years. Previous to that, I spent 7 years working in TV animation and also had a short spell in comics. I studied technical illustration way back in the early 80s in the time before computer aided design:).

Kirill: You move with ease between a number of illustration styles. Is this a conscious decision to diversify and be flexible?

Steve: With my background in TV animation, the ability to change style from one to project to the next was an essential, even lorded part of the game. When I started to sell myself as an illustrator in Ireland, having multiple styles really helped kick start my career. Mainly, I was being asked to produce brightly coloured cartoony type illustration. It had a broad inoffensive appeal I guess.

It was only later that I noticed a style evolving, particularly in my personal work. Initially it was difficult to sell this new style to local clients, but as the style started to gain success in international award competitions it became easier.

I think these days I tweak my style according to the target audience rather than making wholesale changes to it.

Kirill: You seem to be moving away from your earlier cartoony style. Is it hard to let go of something that is not finding its place among the current trends?

Steve: A few years ago I made the difficult decision (financially) to move away from the cartoony style by removing it from my online portfolios.

Doing this helped consolidate my portfolio into a single(ish) style. There’s still a local market in Ireland (and probably elsewhere) for the cartoony style.

Kirill: How has your own stylistic taste evolved over the years? Is there ever a thought of exploring radically different directions? Is there a concern of falling into a certain rigidity of style?

Steve: I think my style is constantly evolving, but by fractions rather than huge leaps these days. Fashion trends are constantly shifting and working in the areas of design and advertising you get shifted along with it. Getting stuck with a style is always something I’m aware of but I wouldn’t say it was a concern at the moment. I use personal projects to experiment with new ideas.

Kirill: Folk art is one of your stronger visual references. What shapes and informs your taste and style?

Steve: I’ve had an interest in history and archaeology for as long as I can remember. My parents house is built on the site of a Roman fort and my father was always digging up incredible pieces of decorated pot, coins and broaches. Over the years this has led to an interest in ancient civilizations and in particular folk art which influences much of my work these days. For centuries pictograms, textiles and graphic iconography have been created all over the world and used to communicate and preserve legends, myths and narratives as a part of daily life rather than for commercial gain.

I love South American folk art, everything from the Incas to the Chachapoya in Peru and particularly the imagery based around the Mexican Day of the Dead (Día de los Muertos) holiday. It’s not just the South American influences, there’s also Asian, African and local Celtic imagery. Medieval Bestiary imagery is also fascinating!

Kirill: What do you think when you look at your own work from, say, five years ago?

Steve: This is the main reason I haven’t designed my own tattoo yet:) I’m always pushing myself, experimenting a little. Sometimes it works, other times it doesn’t. If after 5 years my work hadn’t evolved I’d be very disappointed. Naturally, there are some jobs that I’m still happy with but they would tend to be in areas I haven’t been concentrating a whole lot. I do have a piece of technical drawing I did in college in 1983 that I’m still amazed by. This probably proves my point, as I haven’t drawn a technically accurate bevel cog using Rotring pens and ellipse guides since 1983!

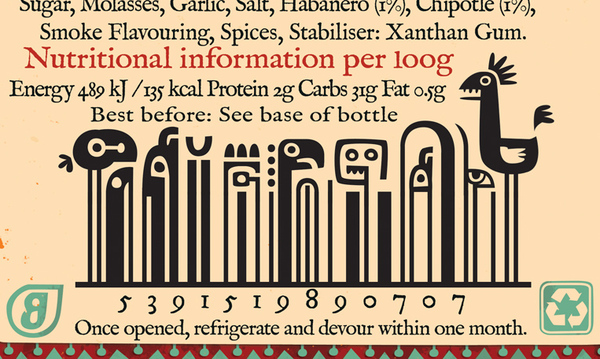

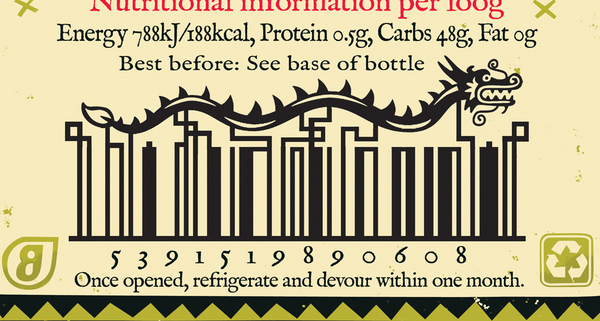

Packaging design and illustration for

BBQ and

Sweet Chilli. Courtesy of Steve Simpson.

Kirill: What draws you into working on physical branding and packaging?

Steve: I like the idea of producing the whole thing, being responsible for the whole design. Especially with packaging projects where you get to fine tune everything down to the tiniest details (I love messing around with barcodes). I like to think of my job on these projects being akin to the commercial artist’s role in ad agencies in the mid twentieth century when they were expected to produce the illustrations, hand lettering, design and even photography and animation. It’s a very fulfilling feeling.

Barcode details for

Sweet Chilli. Courtesy of Steve Simpson.

Barcode details for

BBQ Chilli. Courtesy of Steve Simpson.

Kirill: Do you prefer getting a full artistic freedom for a project, or a more defined direction from the client?

Steve: I like having a definite problem to solve. Too much freedom can lead to a lot of indecision:)

Kirill: Do you keep a sketchbook to develop ideas in between projects?

Steve: I’d like to have one of those beautifully collated sketchbooks, with amazing pieces of art at every turn… unfortunately mine tend to be a mix of hurried scamps, scribbles, lists and the occasional highly considered ink and wash drawing. I’m constantly sketching, mainly on any scraps of paper that come to hand. I’m always planning on sticking them into sketchbooks, but it never happens. My latest idea is an amended version of my previous failed idea, which was to have 2 sketchbooks one for best and the other for scribbles. The amended idea is to have best at the front and then turn it upside down and use the back for scribbles and notes and workings-out…

Kirill: Pen and paper, or digital? How has your choice of tools evolved since you’ve started in the field?

Steve: In 20 years it’s actually evolved very little. It was the early nineties when I first started scanning my pencils and working over them in Photoshop using the vector tool and I still do that now. Along the way I’ve played around with tablets (I’m still using a mouse) and various 3d programs but I’ve always come back to same old method. Works for me I guess:) Previously, when I was working in animation as a background artist, I would have used inks, watercolour, acrylics, collage and even the airbrush.

Kirill: Do you spend time on personal projects, and how important is that for you?

Steve: I always have a personal project on the desk. Something I can work on in between commercial jobs or when I need a break. It’s what keeps me sane!

Kirill: Your site has a special section for children books and projects. Is this a personal passion?

Steve: As anyone knows who works in children’s books, there’s not a huge amount of money involved, you really have to do it for the love. I illustrate a couple of picture books a year. They tend to have long deadlines so I can usually spend the first 2 hours of the day working on one before going back to the tighter deadlines of the design and advertising work.

Kirill: What’s the best thing about being an illustrator?

Steve: Sitting in a coffee shop thinking can be considered working! You can’t get away with that if you’re a window cleaner:)

And here I’d like to thank Steve Simpson for this great opportunity to get a small glimpse into his world. Selected prints are available for sale at Society6 and The Copper House Gallery.

I was hooked from the very first episode. The idea, the script and the cast were phenomenal. And the colors were absolutely gorgeous. Almost too bright and vivid to be true, and yet never flashy or harsh. As I sat down to relive those few precious episodes that saw the light of day (two seasons, twenty two episodes total), I was completely overtaken by how amazingly well this show was put together.

The very first sequence with young Ned running through the impossibly bright field of yellow flowers transitions into the kitchen scene with his mother. Every piece in this set has its place, every fabric and wallpaper lovingly textured with nature-based patterns, and the pop of bright red is a perfect compliment to the earthly yellows, olives and browns.

This style extended to all interior sets, never too vintage to mark any specific era, and yet never modern to break the charming spell of the deeply emotional connections between the different characters. Here’s Olive in her living room, surrounded by blooming flowers on the walls, sofa, pillows, lamp, her pajamas and even the tableware. Delicate, intricate, each with its own color palette, yet none screaming for attention, and all working together in a perfect unison.

Continue reading »

![]()

![]()

![]()