“The Edge of Love” is a small glimpse into the life of a charismatic poet, told through his passion and love of two women. Keira Knightley plays his teenage love that crosses his path ten years later in the wartime London, and Sienna Miller stars as his feisty Irish wife that finds the open-ended marriage as a convenient arrangement to satisfy her restless void.

The dazzling glamour of Keira Knightley adorned with rich florals quickly gives way to a somber surrounding of the underground tunnels of wartime London where small groups of people would gather to forget the horrors of ceaseless bombings. The passing illusion is highlighted in one of the next scenes that shows the lighting technician using a hand-rotated color wheel placed in front of a small improvised stage light:

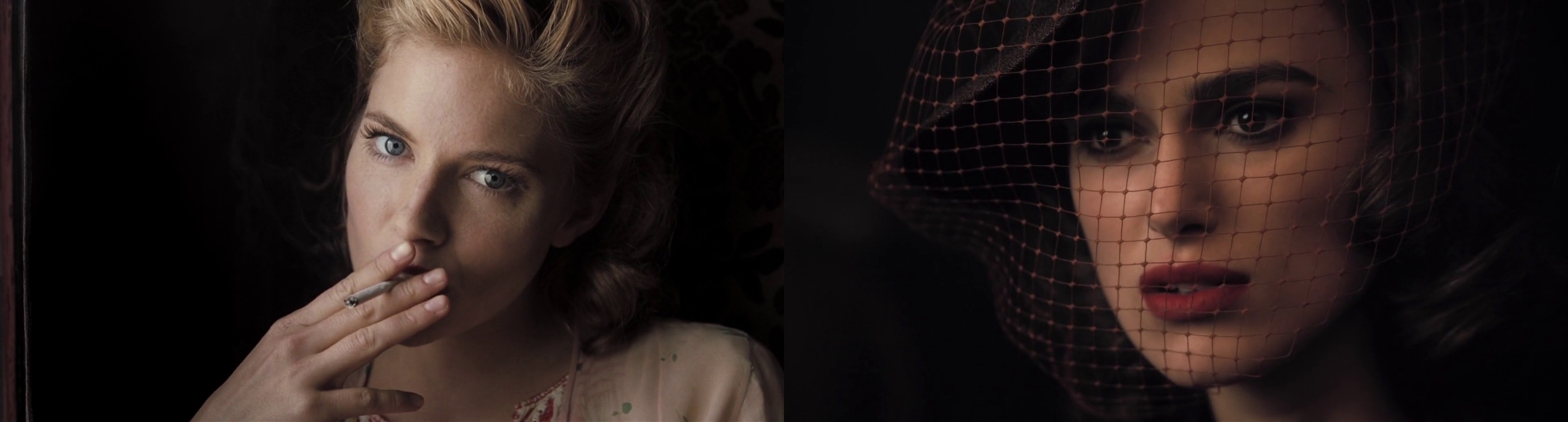

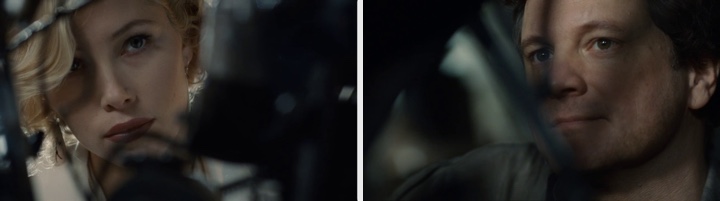

The visual mood is defined by a number of techniques applied consistently throughout the entire movie. As we are quickly introduced to the two female leads, the camera remains steady on their faces, cutting off the top part of the hair:

An intimate look into the strange bond that forms between the two women seems to return to the close-ups, not straying from the center even in the alternating dialog cuts that would usually places the faces on opposite edges. At times the camera lingers on small set pieces

and at times we see the scene through an intricate arrangement of multiple refractive surfaces

The soft browns and yellows of inside scenes are in harsh contrast with heavy grays and blues of sequences shot outside on the backdrop of the sky illuminated by anti-aircraft search lights:

The oppressive abandonment of the streets is captured perfectly by the frame-within-frame in the next shot, as the budding relationship between Keira Knightley and Cillian Murphy (who plays a soldier waiting for his orders to be shipped to continental Europe) is overshadowed by the slanted lines of brick walls and staircases, almost leading the eye to believe that the human couple is about to disappear on the horizon:

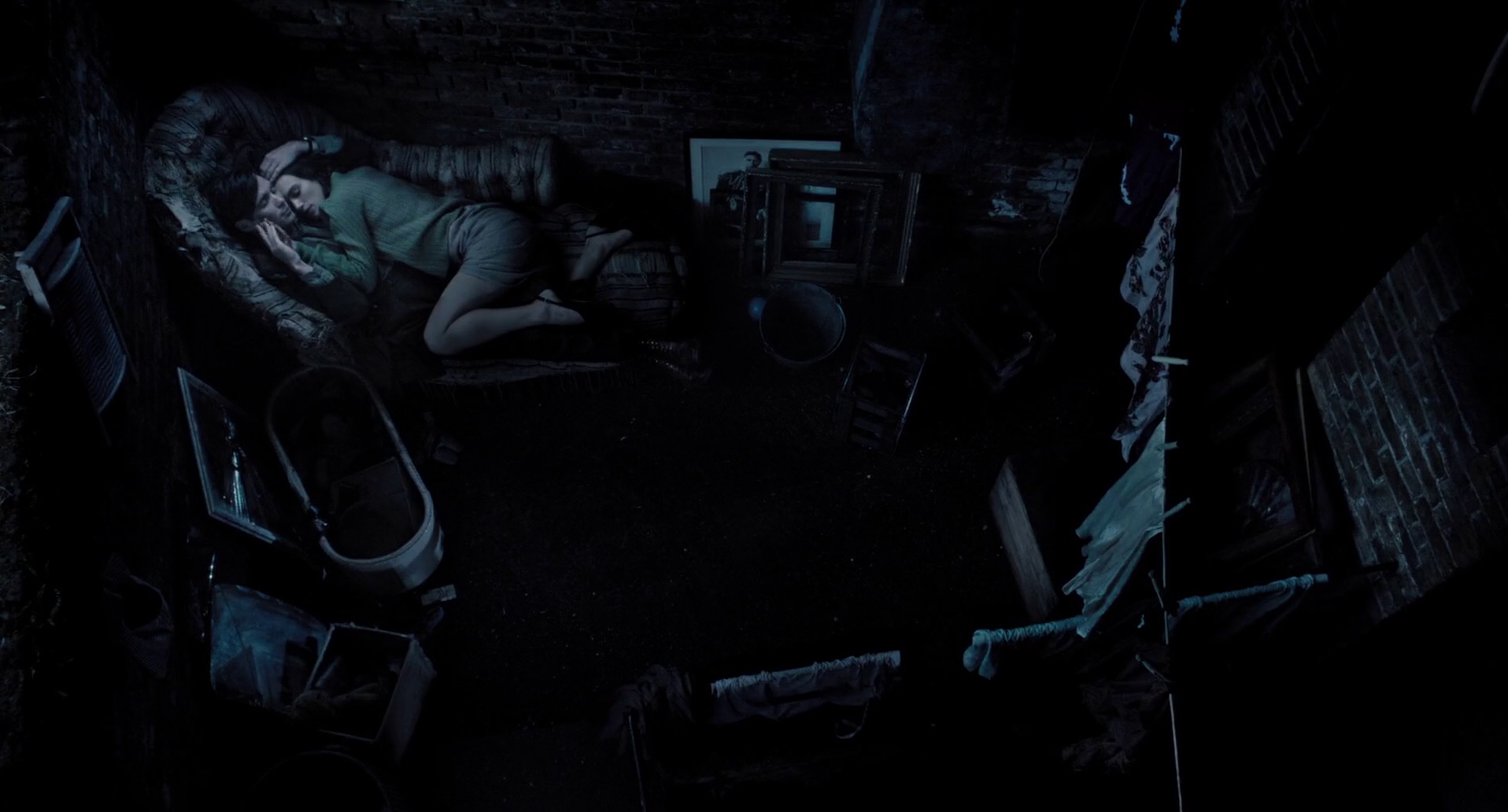

The same composition is applied when the couple is lying on the couch amidst the disarray of household items. The elevated positioning of the camera further adds to the ever-fleeting illusion of hope as he fights to steer her attention away from the rekindled passion for her teenage love:

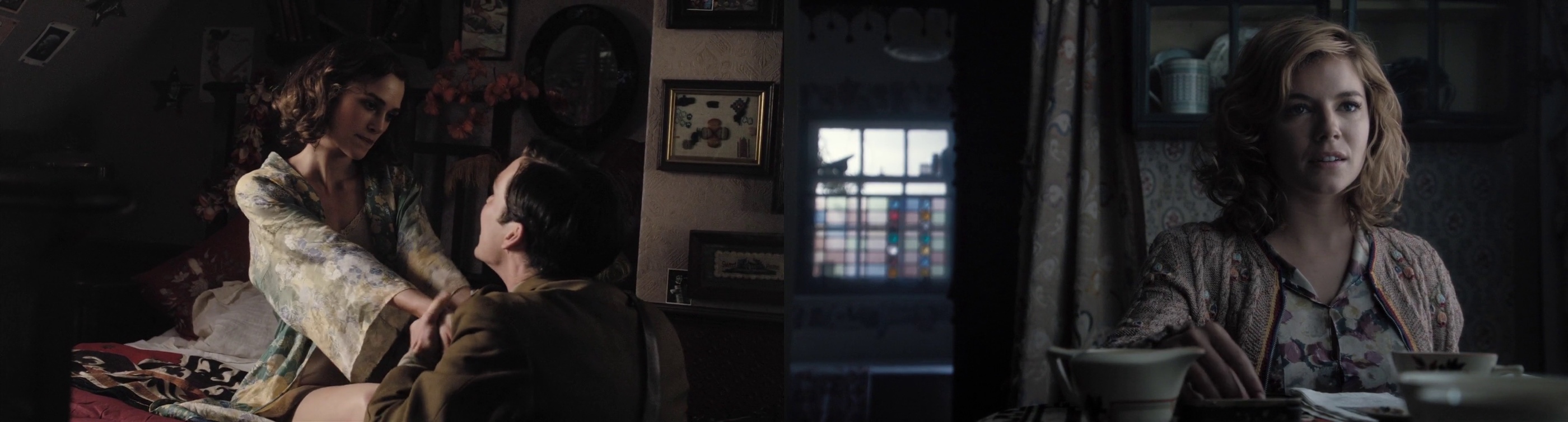

The wartime blackout mandated in the British capital is enforced by stripping almost all the colors from the interior scenes. But even the extremely limited palette of washed out ochre, olive and leather brown is enough to show the characters’ desire to surround themselves with beautiful objects – in this case intricately patterned textures of clothing, wallpapers and drapes:

As the characters are confined to closed interior spaces, the camera spends a lot of time following the rare intrusions of external light. Here, the almost horizon-level sunlight penetrates through the window as a precise light pyramid:

And here, in one of my favorite scenes that lasts for mere seconds, Keira Knightley moves across the floor, as the strong directional light coming from the left creates a beautiful chiaroscuro effect when she gently sways the baby:

The feeling of loneliness in the scene where Keira’s character is reading the letter from her husband, sent across the Europe to fight in the war, is accentuated by yet another frame-in-frame composition, this time combined with slanted window frames reminiscent of the earlier pub sequences:

And a different variant of the same technique, effectively separating the scene into three groups – Cillian’s character standing close to the viewer, the group sitting in the back and the person who they all look at that appears to be behind the viewer to our right:

As the second part of the movie takes place in Wales, we get to see more of the outdoors. In this sequence that brings together a few of the techniques mentioned above, the worn out turquoise furniture is a perfect compliment to the greens and blues of the nature, as well as leather browns of the writing set:

Storyboarding is one of the first steps on a long journey that takes the written word of the book or script to the final finished movie. John Greaves is one of the more prolific storyboard artists in the recent years, with such titles as “The Bourne Supremacy”, “Tomorrow Never Dies”, “The World Is Not Enough”, “Children of Men”, “Chronicles of Narnia”, “10,000 BC” and the recently featured “Emma” on his impressive resume. I’m very grateful to John for kindly agreeing to answer a few questions that i had on the craft of storyboarding.

Kirill: Tell us a little bit about yourself and your path to become a storyboard artist on major Hollywood productions

John: I trained originally in fine art and photography. I started my working life as a photographer, but also drew cartoons and caricatures for various magazines. During the 80’s, I also wrote children’s books. Towards the end of that decade, a friend asked me if I would do a storyboard for a music video he was directing. Through doing that, I realized that this was probably the path I should be going down, as it involved aspects of everything I had been doing up until then.

Kirill: Are you usually the first member of creative team to join the director? What is storyboarding and what is the process of translating the director’s vision of the script into the keyframes?

John: The storyboard artist is usually brought on to the picture early on. There have been occasions where there has only been me, and the director. Usually though, the production designer has started to design sets and find locations. Directors work in different ways. Some have a clear idea of what they want, so I only have to draw up their ideas and fill in gaps, others like you to collaborate more, and some like to leave you to it and see what you come up with. Storyboard artists work in different ways, but I prefer to write a shot-list. From that, I draw a rough thumbnail board, which I will go through with the director. He, or she will then makes any alterations. I will then draw up the finished board.

Kirill: Your storyboards show a lot of attention to camera movement, main action focus and lighting. What visual cues are expected to be in the storyboards, and how detailed are they supposed to be?

John: My personal thought about a storyboard, and this is one that I have expressed whenever I have talked to students about it, is that it’s not about pretty pictures, but about information. For that reason, the board needs to be produced concisely, but quickly and with as much relevant information as possible. I use a lot of arrows with camera moves and will draw as many frames as are nessassary to tell the story.

Kirill: Does it happen that storyboarding changes the initial scripts as the keyframes are fleshed out?

John: Scripts are organic things and change all the time. Locations, sets, stunts, VFX all effect the script and are all reflected in the storyboard. Often the storyboard artist will make suggestions and these usually end up in the script as well.

Kirill: How long do you usually spend on a single movie and how many frames do you typically produce?

John: As I mentioned before, I will do shot-lists and roughs before I get to the finished board stage. The amount of frames I draw depends on the level of finish required, but between 25 and 50 per day.

Kirill: Do you prefer hand sketching or digital tools? What is your actual production process?

John: I tend to draw by hand, then scan it in and render on computer using Photoshop. With this, I can also replicate frames, or parts of frames and put in focus-pulls etc.

Kirill: Your recent work included such VFX-heavy movies as “Prince of Persia” and the sequels to “Ghost Rider” and “Clash of the Titans”. Does it involve more elaborate digital pre-viz sequences?

John: These type of VFX films do generally pre-viz sequences, but only really after they’ve been storyboarded. All of this becomes part of the organic process of film making. Things change all the time.

Kirill: As the industry is transitioning to 3D productions, how does that effect storyboarding?

John: To my knowledge, it does not affect the storyboarding process at all, just makes the shooting process a lot more complicated.

Kirill: Some of your productions, including “Prince of Persia”, “Children of Men” and “Chronicles of Narnia” involved multiple storyboard artists. What is the group dynamics and how is it different from productions where you’re the only one working on story boards?

John: I generally prefer to be the sole storyboard artist on a production, mainly because in theory it means I’ll be employed for longer, but when we work together it’s great. Often nowadays, with it being so easy to transfer large files online, we find ourselves working from home. I’ve just done a film from my home in London when the rest of the production were in Atlanta Georgia.

Kirill: What is the importance of black-and-white story boards? Why the color is excluded?

John: There is no need for colour as a film shooting board is simply that. A document that shows how the film will be shot. Colour would slow down the whole process, for me anyway. Colour is still used on boards for advertising, but that’s more to do with pleasing the clients.

And here I’d like to thank John Greaves once again for his work on “The Edge of Love” and agreeing to the interview.

Take you favorite movie and remove all the actors. You will see a combined creative work of two people – cinematographer and art director. In this conversation Sarah Horton takes a deep dive into the craft of art direction, shedding light on the fascinating fusion of the artistic and financial sides of movie productions. In the last few years Sarah took the role of art director on “The Bourne Supremacy”, “Aeon Flux”, “V For Vendetta”, “The International” and, most recently, “Hanna”. The second part of this conversation focuses on “The International”, an action thriller that follows Clive Owen and Naomi Watts as they unravel the role of a high profile bank in an international arms dealing ring.

Kirill: Tell us about your path so far in the movie industry

Sarah: I never went to film school. I studied History of Art at London university and by chance, my summer job was working at the Edinburgh film festival. This was my first contact with film and it started to really interest me. Shortly afterwards I started working as an Art Dept. volunteer at the National Film and Television School just outside of London and realized that this was absolutely what i wanted to be doing; In those days the Film School only had courses for camera, direction and production so the students with graduate film projects were always looking for help on the design side. After having worked there for a while, I started writing to various designers and after a few more films, started work at Elstree Studios, which was then one of the major studios in UK, where films such as ‘Star Wars’ and ‘Indiana Jones’ were made. This was during the early eighties when many large-scale movies were being made in the UK, like “Labyrinth” and “White Nights”. I started working as the Art Dept Assistant on a movie called “Young Sherlock Holmes and the Pyramid of Fear” directed by Barry Levinson and produced by Steven Spielberg.

Sarah: I never went to film school. I studied History of Art at London university and by chance, my summer job was working at the Edinburgh film festival. This was my first contact with film and it started to really interest me. Shortly afterwards I started working as an Art Dept. volunteer at the National Film and Television School just outside of London and realized that this was absolutely what i wanted to be doing; In those days the Film School only had courses for camera, direction and production so the students with graduate film projects were always looking for help on the design side. After having worked there for a while, I started writing to various designers and after a few more films, started work at Elstree Studios, which was then one of the major studios in UK, where films such as ‘Star Wars’ and ‘Indiana Jones’ were made. This was during the early eighties when many large-scale movies were being made in the UK, like “Labyrinth” and “White Nights”. I started working as the Art Dept Assistant on a movie called “Young Sherlock Holmes and the Pyramid of Fear” directed by Barry Levinson and produced by Steven Spielberg.

Kirill: And so you progressed to assume bigger responsibilities as the time passed?

Sarah: I literally learned my trade within the industry, and consider myself very fortunate to have had this chance. I learned from some wonderful professionals, many of whom are no longer with us. Their background were films like “Dr Zhivago”, “Lawrence of Arabia”, “2001” and of course all the Bond movies and I feel that what i learned was gold dust because it was that old fashioned way of making movies which doesn’t exist anymore. It is the best training I could have had.

Kirill: Do you see a difference between European and US movie productions?

Sarah: Not really. Most of the work that we do here is funded by Hollywood, coming to Berlin or London simply because the rate of the dollar against the local currency makes it economically viable. Most of the movies that i do are Hollywood or American-based productions, and the way they are made is very similar. There are some differences in crew structure, because of the unions but these differences are minimal. However, I also work on smaller local German productions for a very active German market – and they are quite different, simply because there is a lot less money available for each production. Having said that it’s still a market for a population of 80-million, many of whom are happy to pay money to watch movies with well-known stars in their own language.

Kirill: Transitioning into the role of an art director, your job is take the creative vision of director, cinematographer and production designer and make it a physical reality.

Sarah: My boss, the production designer, creates the visual identity of the film. My job as the art director is to realize that identity in physical form which takes the shape of sets and whatever else goes along with the script. The Production Designer establishes a kind of visual scaffolding, defined by color, light, texture and contrast in which I am free to operate. In discussions with the Production Designer, the Art Director is responsible for the construction of the sets and they can take many forms. It can be a set in the studio (like The Guggenheim Museum for “The International”), it can be a location where shooting takes place over a couple of days with minimal or more complex structural alterations of the existing space, including furniture and dressing, or it can be a mixture of both – a “set on location” – where a big set is built within an existing space, using the original features or not, as required by script, budget, logistics and director.

Kirill: In his interview for the “100 Careers in Film and Television” Jeff Mann says that “dealing with money and budgets is probably what I most dislike; trying to put a price tag on aesthetics”. Do you share this sentiment?

Sarah: It’s a constant struggle. As an art director, you’re expected to be both a financial and creative genius, coming up with solutions that don’t compromise the vision of the production designer but at the same time fit within the confines of the budget. It’s a give-and-take process, where the Art Dept budget is spread out over all the sets. However, since one can never predict precisely in advance what the parameters of each set will be, the budget often has to be redivided many times over. It’s a question of being able to manage the money available, but i see this as a challenge not a restriction. It doesn’t matter how big the budget is, there’s always never enough money! Whether you’re working on a $5M, a $50M or a $100M movie, you still end up having the same conversations about what is affordable and what isn’t. I think this is interesting, because it proves that it’s the same process, and one has to think outside of many similar boxes to find solutions to budget problems. I guess that on big budget movies you have the possibility to go into much more detail – which is where the differences lie – more sets, more stunts, more special effects, more options on how to shoot, just more of everything – while on a smaller production you are forced to reduce everything down to absolute essentials.

Kirill: Do you feel constricted when you operate within someone else’s vision?

Sarah: I enjoy the freedom to ‘play’ within an existing framework and find solutions which work creatively and financially. I wouldn’t describe it as being constricted – working with a Production Designer is a process of combining ideas to achieve the vision of the film. Ultimately, anything is possible to recreate – it’s just a question of time and money, so for me, the ‘art’ of what I do, if you can call it art, is when you put those restrictions in, that’s when it becomes interesting for me.

Kirill: When do you start working on the production?

Sarah: I start long before shooting begins, and continue up to the end of principal photography. An average shoot takes between 8 to 12 weeks but since it’s not possible to have all the sets ready and standing in advance of this, I work throughout shooting preparing the sets as they come up in the schedule. During pre-production most of the time is spent working out what each set is going to look like and preparing the construction drawings, surface finishes, stunt and SFX requirements, dressing, etc. Once shooting starts, it’s like a moving train which needs new sets to be ready for shooting sometimes on a daily basis. I’m always working one step ahead, getting the sets ready for the shooting crews, and as soon as they show up, i’m off to get the next set ready, while another team is pulling down the set that they’ve just finished on. I really like my job because i don’t have to stay on set all the time! (laughs)

Kirill: You mentioned that anything is possible. What do you think about digitally-created fantasy environments of movies such as “Star Wars” and “Avatar”? What changes do you see in your craft of creating physical sets?

Sarah: It is changing, and it’s something that i observe more and more often. I think the approach to set building has changed but it won’t disappear. Compared to a production like “Young Sherlock Holmes” where something like 75% of the film were built sets and the rest a mixture of matte paintings, digital effects and animatronics, it’s almost the other way around these days. Having said that, my own experience is that visual effects are often sourced from the built sets using and extending from the physical surfaces and lighting. It’s much more difficult, time-consuming and expensive to start from nothing in the computer. And a physical set also allows the actors to directly interact with it, and all its furniture and props.

Kirill: The make-up designer of “Tron: Legacy” mentioned that almost all productions do reshoots a few months after the main shooting is done. Do your sets stay intact until the post-production is fully done?

Sarah: In the course of pre-production it becomes clear what the key sets are, the sets that are so expensive to rebuild that it makes it worthwhile keeping them with the option of a rebuild. When shooting has finished these sets are flat-packed, that is, they are taken apart and stored. They are kept until there’s a green light on the rough cut, which takes about 2 – 3 months after shooting is finished. The sets are scrapped when the reshoots are over. However, I should add that having the luxury of being able to afford reshoots is something that smaller German productions generally don’t have.

Kirill: How do you feel about the transient nature of what you’re creating?

Sarah: The funny thing is that i don’t mind that at all. I think that’s what makes my job so great – where else can I get to work on building a space ship for example followed by a medieval castle and then an iconic museum? Every set is the sum of many ideas – a statement of the film – and they exist for as long as is needed to tell the story. Film is story-telling. I am always looking for the next story and the next set. I was a little upset was when The Guggenheim was scrapped – it seemed to happen so fast! Striking a set happens in a tenth or less of the time that it takes to build.

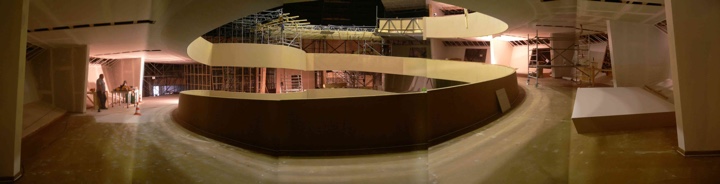

Kirill: The real Guggenheim was not really an option given the sheer volume of destruction left by the hitmen by the end of the scene. In the “making of” video you talk about finding an abandoned structure in Berlin and recreating the entire location there.

Sarah: It was right up the road from the studio and we could walk to it from our offices. It was an abandoned railroad shunting yard, and it was perfect. We looked at a lot of industrial spaces and we needed a span of 40 meters, about 120 feet, across without any pillars. It was very hard to find because most of the structures, like power stations, have some kind of support in the middle; this was the only form of architecture that didn’t have any support structure in the middle and was high enough to enable us to build the Guggenheim in it.

Kirill: And the goal was to create a one-to-one replica of the original?

Sarah: Yes, because we knew that we would be intercutting between the original and the set. For the scenes where Salinger (Clive Owen) looks up at the roof – that’s real. The chandelier that fell down at the end was built and added digitally to the scenes in the original building. All of the fight sequences were shot on our set. There’s a linking shot when Salinger comes in from Fifth Avenue into the foyer – and it was important that this matched to the built set.

Kirill: And even though you did not use all the original materials, you started from the blueprints that you received from Guggenheim, building a sturdy enough structure to support the cast and crew?

Sarah: We worked very closely with the Guggenheim. They sent us the CAD drawings which were tremendously useful. We built it to 90% of the real size, it had to be a little smaller to fit into the space. And we had permanent issues with the walkways, because the scaffolding frame had ramps which were cantilevered out four or five meters. So we knew that weight on the outside edges would be a problem, and none of us really knew how well the structure would hold up to the shooting crew. Crews have a tendency to all gather around the director [laughs] and the first few days were spent moving equipment and people to spread the loads which was pretty time-consuming until everybody got the idea.

Kirill: The Guggenheim sequence lasts about ten minutes in the final cut. How much time did it take you to create the set?

Sarah: We had 12 weeks to build it. I started on the film in April 2007, the construction started around July and we shot on it from September to November of that year – main unit and second unit.

Kirill: Destruction is the main theme of the sequence. Even though there are no explosions, and the building stands after the fight is over, there are thousands of bullets flying around, screens smashing, chandelier collapsing. Is there anything special you do when you build a structure destined for destruction and recreation?

Sarah: We had some complicated breakaway walls. Breakaway walls are squibbed by special effects, who build in charges that recreate the ricochet of machine gun holes when set off electronically, in sync with the action. As the Guggenheim walls are all slightly curved, ramped and slanting, it was a real challenge to set up the breakaway walls. The shootout was shot by the second unit, and there was a phase where we were working in 24 hour shifts. The second unit would come in and shoot all the scenes in the daytime until about nine at night, and then either myself or the 2nd Unit Art Director, Daniel Chour, would get instructions from the first AD as to what would be shot the next day. Then a second shift of craftsmen and SFX technicians would come in and prepare new walls as dictated by the shot list and stunt action. It was very intense, but it was the only way to stay on schedule.

Kirill: There goes your favorite part of not staying on the set

Sarah: [laughs] I stayed overnight with the second unit. The second unit art director and i swapped, with one of us doing the day shift and another the night shift. So yes, i was much more active on this set, while the main unit were shooting all over Berlin on other locations – which was being taken care of by other people.

Kirill: Did you also create the art exposition itself?

Sarah: At a fairly early stage Uli Hanisch the production designer and Tom Tykwer the director began to research the exhibition and as a result made contact with Julian Rosenfeldt who is a video artist. Tom and Julian made a concept together of the exhibition which covered all six ramps since the action plays from the top level down to the foyer. We built a polystyrene model of the entire Guggenheim Rotunda at 1:10 scale which was big enough to walk into, and into which Tom and Julian built the exhibition. Julian supplied all of the video artworks for the exhibition and we installed them using screens and projectors. Organizing this exhibition was a major job in itself for us, particularly because we had two phases of shooting. Initially ramps three, four and five were built followed by a revamp into ground floor plus ramps one and two. Of course the exhibition had to be revamped as well.

Kirill: What about the wide shot of the entire scene that gives a perspective of the overall destruction? Was that added digitally in post-production?

Sarah: No, that was built as a real set. There was an enormous amount of smashed glass on the floor, a mixture of real and rubber glass, much more than is actually visible on screen. So we built the chandelier intact, and a second time completely destructed on the floor. The fall sequence in between was a digital effect.

Kirill: The video exhibitions were integral part of the action sequence, allowing the characters to see each other.

Sarah: That was very much something that Tom took up at an early stage. Julian’s work lended itself very well to the idea that the characters see each other’s refections in the glass panels of the chandelier. There was also a connection between the stories being told in Julian’s videos and the action taking place in front of them. We hid all the projectors in boxes attached to the ceilings which go unnoticed since the eye naturally follows the action. We did have some issues with ‘bouncing’ images when the action was taking place on the cantilevered walkway immediately above. Fortunately you don’t see this in the movie!

Kirill: As you mention the eye following the action, i have a question about people who spend inordinate amount of time trying to find incontinuities or inconsistencies. Does that bother you?

Sarah: Not really! If the story is good enough, the inconsistencies are just a quirky side effect that does not detract from the film as a whole. People who spend time trying to find them are just as much fans as anyone else. There’s one particular shot in “The International” when Clive Owen escapes and there is a whole section of wall which simply does not exist in the museum itself. I guess that anyone who knows the geography of the Guggenheim might have noticed this, but it still doesn’t detract from the story, in my opinion.

Kirill: Do you spend extra time on such long scenes to make sure that you maintain consistency throughout the shooting?

Sarah: We do. Storyboards are really important for long action scenes and help to maintain continuity. We spent a great deal of time making sure that there was consistency on the bullet holes. We didn’t shoot according to the script and because of this, the number and position of the bullet holes varied, depending on where we were in the sequence. So we made huge templates using dust sheets to mark the position of the bullet holes for each section. This way we always knew where the bullet holes were supposed to be depending on which sequence it was. Even though this all happens in the background, it’s important to get this correct otherwise the audience would be distracted from the action.

Kirill: Did you spend time on other sets? I was particularly impressed by the bank headquarters, with very stylish and spartan furniture, designed and arranged in a very attractive manner.

Sarah: That was another location in Germany about two hours from Berlin. It is the headquarters of Volkswagen in Wolfsburg, and the foyer with the globe is the main reception area. We also spent a lot of time on the interior of the offices rebuilding and converting several modern glass-and-steel Berlin office locations. It was an important element of the design that the coolness and minimalism worked within a realistic and believable environment without getting too ‘James Bond’ or futuristic.

Kirill: What about the overseas locations in New York and Turkey?

Sarah: When a movie shoots in several different countries you generally have an art director for each country. I was the art director for Berlin and Germany, which was the main chunk of the shooting. There was another Italian art director who did Milan and Turkey, and we had another local art director who did the last ten days in New York.

Kirill: Was it your most challenging production?

Sarah: Yes, I think it was the most challenging up until now and certainly one of the most fun as well.There was a great crew and the construction team was amazing. Recreating something like this is always about teamwork and I think everyone can be a little bit proud of what was achieved. Even if it was a one-to-one copy of an existing building and not ‘design’ in the purer sense, it was still a tremendous professional challenge and I am very happy to have been involved in it.

Kirill: Closing the loop on the evolution of digital productions, do you see your craft changing in the future?

Sarah: I see it changing, but i see that there will always be a demand for film sets. I think it’s important to keep up with new technologies and new software. It’s no longer just working by hand doing pencil drawings, but at the same time i don’t think that this will disappear either.

Kirill: Does it bother your eye to watch digital productions with computer-generated environments that, perhaps, lack the warmth of real-world textures and shadows?

Sarah: I thought “Avatar” was absolutely stunning. I enjoyed every minute of it, and it’s a huge achievement. I also think that 3-D means more people going back to watch movies in the cinema, at least in the short-term until 3-D television makes it into our homes. On the other hand, some of the great American TV shows such as ‘Game of Thrones’, ‘Boardwalk Empire’ or ‘Mad Men’ show that set design is alive and well! So I think it’s hard to predict the future; ten or twenty years ago nobody could have said or predicted what is happening now.

Kirill: Can you recommend some of your favorite movies, from the professional standpoint and in general?

Sarah: “The Assassination of Jesse James by the Coward Robert Ford” is my favorite production designed movie of the last few years. It’s so restrained but full of detail – i absolutely love it. I guess I’m a fan of design that supports but doesn’t overwhelm the action. Another favorite has to be “Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind” – Jim Carrey is a fantastic actor. And “A Series of Unfortunate Events – Lemony Snicket” – the design is so playful and crazy.

Sarah has also graciously agreed to share a few behind-the-scenes photos of the Guggenheim recreation, conveying the scale and complexity of the construction process:

I’d like to thank Sarah for this fascinating peek into how movies are made or, in her words, “the artifice of illusion and the thin line that exists between what the brain accepts as ‘real’ and what not”. And here i leave you with my favorite establishing shots from “The International”:

Production design: Uli Hanisch

Art direction: Sarah Horton, Kai Koch, Luca Tranchino, Jennifer Santucci

Set decoration: Simon-Julien Boucherie

Costume design: Ngila Dickson

Cinematography: Frank Griebe

Director: Tom Tykwer

“Easy Virtue” is set in the late 1920s, following the story of a young American race driver played by Jessica Biel as, after an impetuous marriage, she arrives with her husband to his family home. A battle of wits between her and his mother starts almost immediately, swinging between comedy, romance and, at times, melancholy. The title sequence sets a nice visual mood, transitioning from the balcony view of an old movie theater into a semi-documentary scene of Monte Carlo racing, all set in faded sepia monochrome colors:

Stylish costumes and striking bleach blonde hair arrangement are reminiscent of Hollywood glamour era of Mae West and Jean Harlow:

The family house is a vast mansion crowded by furniture, hunting artifacts, embroidery, sculptures and never-ending book shelves. As the camera moves between the rooms, it lingers on ornamental mirrors, adding yet another layer of depth to the beautifully arranged interiors:

Mirrors play a central role in one of the more emotionally charged scenes; the camera catches the two characters in both mirrors, while they are talking to each other’s reflections. Also note the rich beige-brown color palette with just a touch of golden sand:

Jessica Biel’s character, Larita, struggles to find her place in this turbidly quiet setting, resorting to spend her time reading books and waiting to get back to the bustling landscapes of the big cities. Note how much lighter the color palette of this scene is when all heavy wooden browns are taken from it; even the deep vermillion brown of the upholstery is very relaxing:

Larita finds a few moments of peace in a rather unexpected place – the garage where her father-in-law (played by Colin Firth) spends his days away from the family. Note the much cooler soothing grays with an almost imperceptible touch or laurel green:

This is one of my favorite scenes, and the only one where there is any real intimacy in human conversation. This is also the only place where the shallow depth of field places the viewer directly behind the blurry pieces in front of the main characters:

As Larita’s struggle to convince her husband to leave stretches into the winter, so does the entire visual mood of the movie. Here, a rare outside scene with the sun washing their faces and green moss covering the branches:

And here a much more subdued mood, with heavy browns and blues taking over:

I am quite fortunate that Mark Scruton, the art director responsible for these beautiful sets, agreed to answer a few questions about the movie itself and the industry in general.

Kirill: Tell us a little bit about yourself

Kirill: Tell us a little bit about yourself

Mark: I’m a freelance Art Director living and working in London. I wanted to work in the film industry ever since I watched “Krakatoa: East of Java” at the age of 6. I trained at the Bournemouth Film School and have been working in the industry for the last 15 years. In that time I’ve had the privilege to work on a wide selection of challenging projects.

Kirill: Can you elaborate on the initial design phase where you work with other production departments to define the visual language for each movie scene?

Mark: Filmmaking is always a team effort. One department can never exist in a vacuum. This was especially so on “East Virtue”. Stephan Elliott, the director, had very clear ideas on the look and style of the film right down to specific dressing and even colours. Obviously this was a period movie, which gives each department an immediate starting point but Stephan wanted to play with this. He wanted to use a more modern style of filming and he wanted to play with the period look to establish the differences between the characters. John Beard the designer, Niamh Coulter the set decorator and myself spent a long time in pre production visiting locations with the director and DOP (director of photography) trying to find just the right style of environment that also gave him the angles and relationships within the layout for what he wanted to achieve. There is no point in finding an amazing location if you all turn up and you can’t film it!

Kirill: Do you spend time designing and refining a complete set, even if some parts of it will never be captured on camera?

Mark: Yes, more so these days than ever before, for various reasons. Attention to detail and creating a “complete” environment is vital if a set is to be believable to an increasingly sophisticated audience but also to the cast and to some extent the crew as well. Film making is a lot more organic than it used to be and there is never any guarantee that when a director arrives on set he won’t turn his camera 180 degrees in the opposite direction, so you have to be covered. That said if it’s a tiny scene and you have a limited budget you have to try and cut your cloth accordingly. It’s always a bit of a balancing act.

Kirill: “Easy Virtue” takes place not long after the First World War. How do you research and recreate a look of days long gone? Do you strive for complete authenticity?

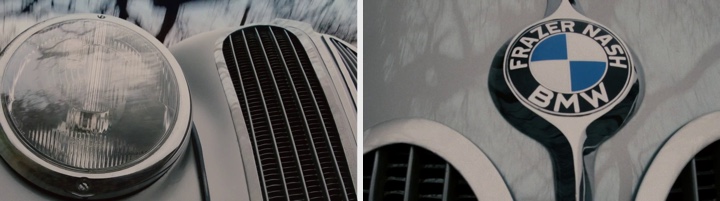

Mark: When you’re doing a period film the design is entirely led by research and you always aim for complete authenticity. Research is normally a mix of reference books, expert advice and personal knowledge. On “Easy Virtue” things were a little different though, as Stephan wanted to emphasize the difference in the characters using amongst other things, the props and dressing. So we had a bracketed time period rather than one specific date. The idea being that the Whitaker household was at one end and Jessica Biel’s character, Larita was very much at the other. Her car, accessories and wardrobe were all about 10-15 years later than everything else in the film and were specifically chosen for their “futuristic” look. The idea was to make her character look extremely incongruous and the Whitaker family, look antiquated and stale.

Kirill: Vintage cars and motorcycles are featured amply throughout the movie as the main passion of Jessica Biel’s character. Do studios have vast stocks of these vehicles, or do you obtain access via more exotic means (museums, private collectors, plaster molds on modern cars)?

Mark: Nearly all-period vehicles on films are sourced from collectors or enthusiasts. Michael Geary was our action vehicle co-coordinator. He helped us track down the specific cars required or gave us options based on our brief. Jessica Biel’s car was the hardest. It needed to be silver, stylish & conceivably usable as a racing car but also needed to be a two seater with a trunk, not very common even for the later time period that applied to her character. We ended up using the BMW 328 as it fitted all the criteria except it’s production dates were slightly later than we wanted but it was too good not to use. In the end it all helped to highlight the differences of Larita’s world even further and it was a beautiful car. We used this device again with her motorbike. The bike she finally rides at the hunt is actually a later model than the one she is seen working on with Colin Firth. It was faster and more able to cope with the off road terrain plus it created a far greater juxtaposition with the horses.

Kirill: Apart from a few short scenes, the story takes place inside the spacious family house. How does a limited environment affect your designs for scenes with different emotional moods?

Mark: The house was in fact three different houses, chosen specifically for this reason. No one house had all the right scale rooms and exteriors for what we required. Blending different locations meant we could have exactly what we wanted in terms of scale and look. Even with this freedom we still couldn’t find the right environment for the re decorated suite of rooms that Mrs. Whitaker offers up to John & Larita. So we built it as a set within the theatre hall that would later become the “War Widows Review.” All the different locations were linked by pieces of set that carried the architecture through from one house to the next so hopefully audiences were none the wiser.

Kirill: Do you find yourself planning unrealistically large indoor sets to accommodate multiple camera angles and wide shots showing group scenes?

Mark: If you are building sets you normally have the flexibility of wild walls. That is, stretches of wall that can be removed to allow crew, equipment & camera to be outside the room you are filming in. If you are on location you always consider this and plan accordingly. Sometimes it can get a bit cozy in the smaller rooms but there is normally a way of getting what you want.

Kirill: Your work has spanned multiple genres, from Geonosis dungeons in “Star Wars” to stalactite caverns in “The descent”. Do you seek challenge working in such a variety of target environments?

Mark: The variety is one of the things I like about this industry. As a jobbing Art Director with a mortgage you generally have to take the work that comes your way. I’ve been lucky that most of the projects I’ve worked on have been varied and interesting, one minute you’re researching the past next you are inventing the future. It’s all part of the fun.

Kirill: Your portfolio shows an impressive level of detail in your sketches and final constructed sets for TV commercials. How different is your approach for these extremely short, but very frequently viewed spots?

Mark: In dollars per second, commercials can be as, if not more expensive than some films and will probably receive more scrutiny. You have three tiers of decision making, client, ad agency & director – all of whom have their own ideas. So they require as mush attention to detail as a film if not more, plus you are normally working within a corporate identity, which is often tricky to balance against the director’s creative requirements. It can make life very interesting.

Kirill: How is the movie production craft changing with progressively more movies shot on green screens, creating the entire environments with digital tools?

Mark: Certainly we are entering a new era of movie making. The digital palette is growing at a rapid pace. The film I have just finished was a very interesting mix of traditional movie making, tried and tested VFX and absolute cutting edge technology. If the whole thing comes together it will definitely open up some new and exciting possibilities. However I think movies will always be shot in a manner that is appropriate to the subject and story. “Easy Virtue” would be shot roughly the same way if were shot now, or in 20 years time.

Kirill: What are your favorite movies over the years that you can recommend us?

Mark: That is such a broad question, as different movie resonate at different points in your life. I guess the two that have had the greatest impact (aside from Krakatoa & Star Wars) have been Terry Gilliam’s “Brazil” & Terrence Malick’s “The Thin Red Line”. Both movies had a profound effect on me when I first saw them and I still find things in them that amaze me.

I’d like to thank Mark once again for his wonderful work on this movie, and for graciously agreeing to this interview. You can visit his portfolio page for “Easy Virtue” to view additional sketches and photographs. And here i want to leave you with another one of my favorites. A scene that lasts, perhaps, a mere 10-15 seconds, but manages to convey so much joy, energy and youthfulness of the blissful couple, just before they are sucked in to a power struggle that slowly corrodes their marriage:

Production design: John Beard

Art direction: Mark Scruton

Set decoration: Niamh Coulter

Costume design: Charlotte Walter

Cinematography: Martin Kenzie

Director: Stephan Elliott

It seems like every time I watch “Tron: Legacy”, I find yet another visual layer to explore and enjoy. After talking with GMUNK about the visual effects, it’s time to take a deep dive into the beautiful world of Tron make-up. With X-Men, Fantastic 4, Watchmen, Sucker Punch, Tron: Legacy and the upcoming Underworld (just to name a few), Rosalina Da Silva has one of the most impressive resumes in the world of big budget sci-fi movies in the last decade. I’m very honored to host a conversation with Rosalina, starting from her work on Tron and later touching on the general craft of big screen make-up wizardry.

Kirill: Can you walk us through the process of interacting with different art departments and defining the visual look of the movie and the characters?

Rosalina: It depends. Sometimes I’m given a script, and other times – for example for Sucker Punch – I had access to a DVD that showed the concept and vision of the director. You start working on the script or these materials, and in general you do a lot of research. I research photographers, for example David LaChapelle and others that are very creative in the looks that they achieve. I go through different types of magazines and movies, trying to create something. I research the latest make-up looks of the European runways, I watch what the make-up artists are doing on those shows – it’s always a great inspiration. You cannot bring those shows to the screen, but you certainly be inspired by them.

Kirill: Do you pitch a few different looks?

Kirill: Do you pitch a few different looks?

Rosalina: Usually i’ll build a book for the movie i’m working on with images and tearsheets from magazines, and i’ll show my ideas to the director, and then he’ll let me know if i’m on the right track. We start there and then narrow in given the director’s feedback and the look that he wants. Then we start testing and testing and testing and trying to achieve the look that they want. We’ll do the make-up tests to see how it looks on the screen; when you put it on the screen it’s different from how it looks on paper.

Kirill: At which point do you start working with hair stylist and costume designer?

Rosalina: Pretty much straight away. Makeup and hair stylist / designers usually get hired at the same time. Often the costume department starts earlier, so when we go in, we look through their sketches and the color scheme that they’re going for; that’s another inspirational point to look at everything they’ve done so far. And the same is true production designers and everybody else – Often they’ve been in production for months and had a lot of meetings. You look at the sketches and their vision for the movie, and that’s your main source of inspiration for the movie – to complement the work that they’re doing.

Kirill: Do you tweak your work based on the actual set lighting or preliminary post-production treatment?

Rosalina: Usually we tweak the looks once we get the actors. Sometimes the look does not complement the actor, so when they come in, we try to put our ideas on the skin and facial structure and make sure it all works together. They also have an opinion which we listen to, and then we do the make-up tests on screen.

Kirill: And you’re on the set every single day?

Rosalina: Exactly. We come in in the morning before everybody else, we get the actors ready for the day and then we go on set. Sometimes there are changes throughout the day if they shoot different parts of the movie, so you have to change the look, adding or taking off what is necessary.

Kirill: As I was looking for some background on your work, I happened upon a site that details dozens of products that go into the final look for one character. How much do you need every day to create that look?

Rosalina: Obviously the production wants to make it as fast as possible. The actors need to have some time off, and there’s only so many hours during the day that they can shoot, and of course they’d rather have them on set rather than sitting in the make-up chair. Some looks can be done in an hour or an hour and a half, including make-up, hair and wardrobe. It depends on how intricate the look is and how much works has to be done.

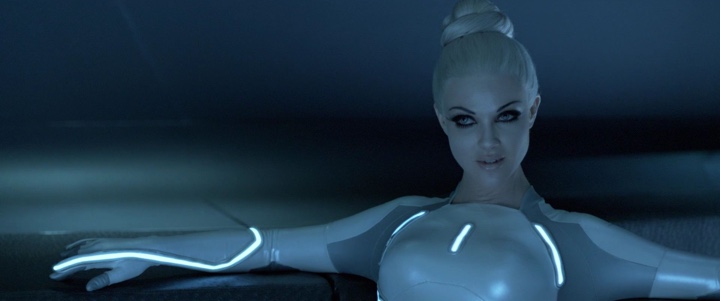

Kirill: Most of the story happens in a computer world, with very stylish black and white environment and precise lines. Was it an interesting challenge to create a look for what are essentially computer program characters?

Rosalina: Absolutely. Honestly, when I first read the script I didn’t know what to do. It was challenging for me at the beginning. But as I said, the costumes had already been designed, so I started looking at the sketches. Our director [Joseph Kosinski] has background in architecture and he loves simple straight lines. I knew that whatever we had to do for him had to be very clean and streamlined. And since it was all very new to me, with computer world and a 3D production, I had to keep it very simple to make it stunning, sexy, beautiful and appealing to the eye. So me and my team started to work, and we decided to keep it monochromatic – the colors of the grid – and to develop the black and white make-up with straight lines.

Kirill: It resonates nicely with the binary nature of the computer world, zeroes and ones, black and white.

Rosalina: It was that. You look inside the computer and you see the structural grid, and you take all the little shapes from there and create those shapes on different faces.

Kirill: When you start with the surrounding set design and costume, how much freedom do you have in designing the looks of the specific characters?

Rosalina: I had all the freedom that I wanted, being inspired by this. The challenge is to work with the costumes, to make sure that this person looks amazing with the costume, the make-up and the hair.

Kirill: Even when you remove all the skin and lip color?

Rosalina: Exactly. The original design concept of the Sirens had a mask over their mouth – but that was not looking quite right. Things evolved and changed, and I decided to go for a nude lip, to create a naked look on a shapeless face, removing any redness on the lips, making it blend and bringing a lot of attention to the eyes. I wanted them to be dolls, since they were made by the other characters – flawless dolls with big eyes, just stunning women.

Kirill: The club scene in the “End of Line” has a lot of supporting cast, and every single one of them has his or her own style. How much effort do you spend on the supporting characters and how important is it to have a complete look for everybody?

Rosalina: Very important since they are part of the scene since they must belong there and support the main cast. On the day we were doing that scene we had 21 make-up artists to get everybody ready. Everybody was fitted for hair, make-up and wardrobe to suit the whole look, and every single make-up was designed prior to that day. We put all the looks in a book, showing it to the director every day or so, and he would choose the looks that appealed to him.

Kirill: Do you work with stand-in replacements for a big scene like this?

Rosalina: We used the actual background actors. They would come in for fitting, and he or she would be designed on. They came for 3-4 days before starting the shooting, and we designed every single face.

Kirill: A scene like this is not shot in one day?

Rosalina: It takes a few days to shoot such a scene, maybe a week. We had quite a few scenes where the challenge is to make sure that different actors in different scenes do not have the same look. We had different types of programs in the script and we didn’t even have common names for them like people do. The whole script was computer language, and it was quite a bit of a challenge for me [laughs].

Kirill: For these multi-day scenes, how do you make sure that the look is consistent for the final cut?

Rosalina: We make charts to help with the continuity of the of the make-up…on a day to day basis, taking close-up photos and writing down everything we do – to have full references. We do continuity photos for everyone, not only for the next day, but also for reshoots six months later. We reshot some of the scenes in the lightcycle game, and you can barely see it.

Kirill: That’s the best outcome where the viewers can’t tell. What’s the reason for the reshoots?

Rosalina: Sometimes during the editing they want to make a scene more complete and have extra footage. Sometimes you want to develop or enhance a character a little bit more. This comes up at the end of the shoot when they start editing and putting the movie together. It hardly ever happens that there are no reshoots.

Kirill: I saw a few faces with deep scars running across. Was it part make-up, part computer-generated?

Rosalina: That was Bill Terezakis who designed the scars and the half-face man. The scar was fully make-up, and the half-face man was computer graphics together with make-up.

Kirill: Is it more fun to work on villain characters, like Castor and Jarvis?

Rosalina: Both characters were very challenging. We shaved James Frain’s head and bleached his eyebrows for his Jarvis character; most people don’t know who he is. And Michael Sheen underwent a total transformation as well, with the wig and full beauty make-up. He was wonderful to collaborate with, giving us ideas and taking inspiration from Ziggy Stardust. The Sirens were also very challenging and fun make-up to do. I kept Garrett very simple; as a human it was very important that he didn’t look like anybody else on the grid. I did a little bit of corrective make-up to just show off his good looks. Quorra could not look like a Siren, she had to be more human. She was undercover, hidden away, so she had to look different, but not very noticeably different. Olivia Wilde is a stunningly beautiful woman, and we had a lot of choice with her character.

Kirill: How did it feel to see the complete look on the set?

Rosalina: We went to the set for the nightclub scene, and my jaw just dropped. I have a group of very talented make-up artists that give me their best. I put my ideas, but at the end of the day they execute the job. So you never know how it will look like until you get to the set. I did my actors and arrived at the set, and it was absolutely amazing. To see the whole thing, the costumes, the make-up, the sets, everything together was just amazing. We were sitting in the basement for over a month creating, designing and developing looks and one of the producers said to me: “So this is what you’ve been doing?”

Kirill: Now that we’ve talked about Tron, perhaps we can turn to a more general conversation. You’ve started in the late 80s and 90s on TV movies and then transitioned to the big Hollywood productions. Was there any specific reason for this move?

Rosalina: You always want to do bigger and better, and that was it for me. I always look for the opportunities to work with amazing creative people. I believe that the ultimate product is the combination of a lot of people working very hard and working very well together. It just happened that I transitioned to work on sci-fi movies; I was just lucky to get those calls. You build a body of work and you keep on going and working very hard, and then you get the job and you’re very thankful. Many years ago in the television we didn’t have a lot of challenges in make-up, but nowadays people are doing beautiful work. And it was certainly great to venture to the big screen and do all this work. I am grateful every single day to have this chance.

Kirill: Is your work made more difficult by the high-definition projection systems, TV sets and BluRay discs where the viewers can see every single pore on the actors’ faces?

Rosalina: Yes, you have to think about this really seriously. You have to make good product choices, to choose the products that suit the screen. Everything – the big screens, high definition, 3D – is making your work very difficult. What I try to do is to go easy and simple, to do the simplest design I possibly can and leave as little room as possible for errors. The worst thing is the difficult skin with pores, pimples or breakouts that you cannot hide. Lighting plays the biggest part, it can make your job look beautiful or bad. I leave the lighting to experts and my job is to bring any particular challenge that I have to their attention and ask for their help. Otherwise I watch and learn and adapt.

Kirill: “Sucker Punch” is your latest release. Was it more fun working with colorful palettes for all the girls?

Rosalina: We went from one extreme to another. Zack Snyder is a genius director. He gave me a carte blanche, saying that he wants it to be very theatrical and big. The question is how much is too much – you just push the envelope and listen to what he says. My job as the make-up artist is to bring the director’s vision to the screen, to learn from the script what is the vision and do the best I can in order to create that.

Kirill: Are male actors less open to the experimentation with make-up?

Rosalina: The male actors in my last two movies were very willing to wear a lot of make-up. All the boys in “Sucker Punch” wore make-up, it was very theatrical, very film noire. And the same for the male characters in “Underworld” that I just did. This is especially true when you’re working with theater actors that are used to wearing make-up and playing different characters – they love to explore and they love to look in the mirror and see the character.

Kirill: And before that you worked, among the rest, on two “X-Men” movies. These movies have the human characters that transform into different mutants with non-human skin and faces. Do you have make-up artists creating the facial look and expressions for those characters?

Rosalina: There was a separate team working on the mutant characters, together with the visual effects people. The make-up artists take a look to a certain point, and then the VFX comes in and takes it further. You take it to a particular point, as far as the skin tone and shading, as far as you can and then hand it over to the visual effects. I also worked on the movies with prosthetic pieces and aging, where a separate team would apply the pieces and i’d do the make-up on top of the pieces to keep the continuity. For example, on “Watchmen” when Carla Gugino ages, Greg Cannom did the aging pieces and the I did the beauty make-up on top of it to keep the whole look.

Kirill: The advances in the capabilities of visual effects make it possible to go beyond non-human characters and experiment in creating fully computer-generated human ones. For example, the CLU character in Tron is a younger “version” of Jeff Bridges. Do you think that a human face can be done realistically at the present moment or in the near future?

Rosalina: Maybe in the future. I think it’s still very questionable and not completely perfected. Of course everything changes, and every six months there’s a new way of doing things; it’s unbelievable how fast visual effects evolve. It’s the eyes, the mouth and the skin texture. I think the skin texture is hard to achieve, and it always looks so smooth and plastic while in reality it’s not quite like that. But whatever they do is amazing, we couldn’t even think about doing that years ago.

Kirill: And in the future where these capabilities are more realistic, how is your craft affected? Do you see make-up artists reduced to specifying the overall look, and the post-production stage applying that look?

Rosalina: I hope that never arrives. I hope the human touch is always there. I think there’ll be a place where you take the artists in the morning and you transform them visually in the computer, but it’s going to be incredibly expensive. In my humble opinion, there’ll always be place for the human touch and contact.

Kirill: It’s quite fascinating to see how the landscape of movie making is changing as compared to a few decades ago. Can you recommend a few movies that keep on inspiring you?

Rosalina: If you think about any of the old movies, like “Casablanca” or any of Fellini movies, don’t we reminisce about how wonderful they are? The contrast was quite amazing, with very blunt use of saturated colors. When I do my research for movies, I always watch Fellini to get inspiration. “Sweet Charity” with Shirley MacLaine is the first movie he did in US and I just love the incredibly beautiful visuals. I like to watch the old French “Casino Royale” with Ursula Andress and David Niven, it’s visually stunning. “Juliet of the Spirits” was the first movie were Fellini used color and “8½” are some of my favorites. “La Dolce Vita” of course. How can you not watch “La Dolce Vita” with Marcello Mastroianni. And “Fellini’s Roma” is another great one.

You can find Rosalina Da Silva on her blog A More Beautiful Makeup, on Facebook and on Twitter.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()