If you’re new here, let me introduce myself – I’m a giant fan of “Tangled”. It doesn’t happen a lot, but when it does, it sweeps you off your feet. A visual journey so wonderful that you catch yourself watching it over and over again, discovering yet another subtle layer of colors, textures, strokes and shapes. A splendid feast for your eyes that passes by in a blink of an eye without you noticing how the time has passed. In short, a movie that sets the bar so high that you never expect another movie in the same genre to be quite on the same level.

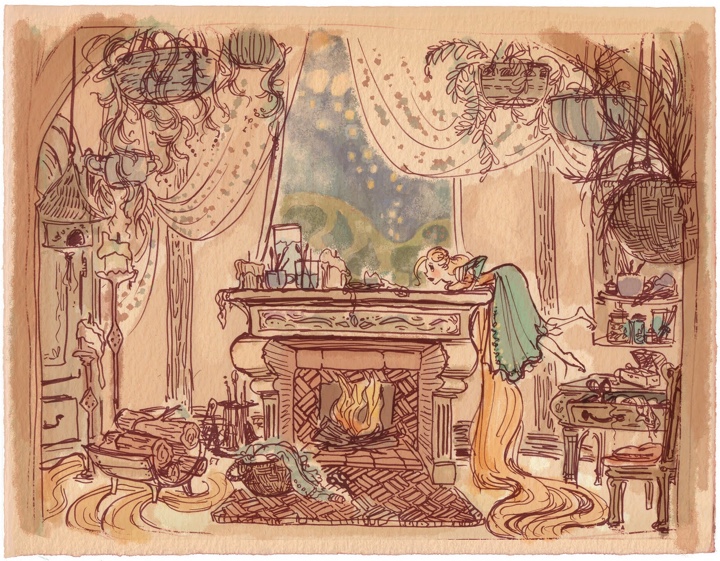

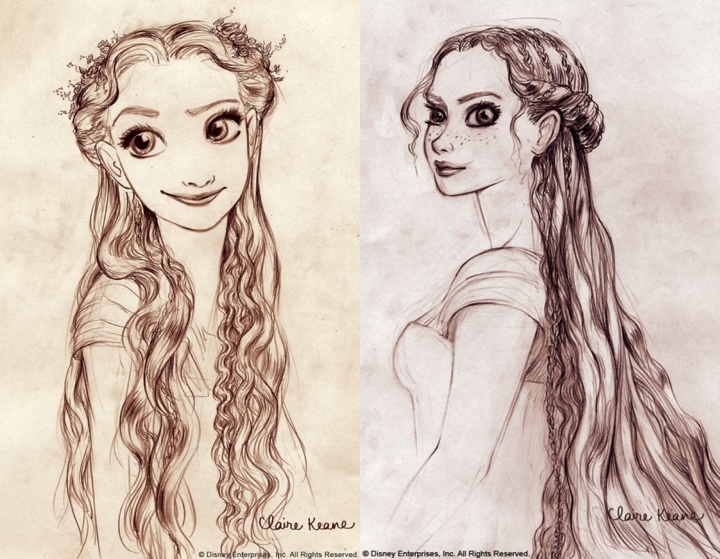

So you can only imagine my excitement when Claire Keane has graciously agreed to answer a few questions i had about her work on “Tangled” and the animation industry in general. Going under the rather dry title of “conceptual artist”, Claire’s work spans the entire movie, from the leading characters to Rapunzel’s surroundings – not to mention the intricate details of her magic hair.

Kirill: Tell us about yourself.

Claire: I grew up in southern California until the age of 16 when my family decided to move to France for a year. After one year our family loved Paris so much we stayed many years thereafter. After graduating from the American School of Paris I went to Parsons School of Design in Paris for one year thinking I would like to go into fashion design but soon enrolled in the Ecole Superieure D’arts Graphiques realizing that illustrating and drawing was really my passion. In my fifth year at ESAG, I chose to write and illustrate a fairytale book for my thesis project. It wasn’t until then that I realized how much I loved the development phase of a project. When “Tangled” came to the point where they needed to bring people on to develop Rapunzel’s world I was ready to go with my thesis project in hand as my portfolio.

Claire: I grew up in southern California until the age of 16 when my family decided to move to France for a year. After one year our family loved Paris so much we stayed many years thereafter. After graduating from the American School of Paris I went to Parsons School of Design in Paris for one year thinking I would like to go into fashion design but soon enrolled in the Ecole Superieure D’arts Graphiques realizing that illustrating and drawing was really my passion. In my fifth year at ESAG, I chose to write and illustrate a fairytale book for my thesis project. It wasn’t until then that I realized how much I loved the development phase of a project. When “Tangled” came to the point where they needed to bring people on to develop Rapunzel’s world I was ready to go with my thesis project in hand as my portfolio.

Kirill: How long have you been working on Rapunzel? Has it been an all-consuming adventure or a more structured “work” project?

Claire: I worked on Tangled (Rapunzel) for 6 years with a small break to do some work on Enchanted. Working on Tangled was an all-consuming adventure – I like it best that way.

Kirill: Where do you find your inspiration?

Claire: I usually find inspiration in other artists. A few that I tend to come back to a lot are: Matisse, Rembrandt, Klimt, Marie Laurencin, Ronald Searle.

Kirill: What is your preferred drawing medium and why?

Claire: I love pen and ink for the simplicity of being able to do it anywhere but since I’ve started using photoshop so much I have become completely addicted to the undo button… and I find it very hard getting back into using *real* medium again.

Kirill: How do you recreate the world as seen through the eyes of a girl that has spent all her life locked away in a tower? How much of yourself have you channeled into the fabulous wall paintings?

Claire: For Rapunzel I drew my inspiration from my own life. Early on I realized that the paintings on Rapunzel’s walls were going to be a representation of Rapunzel’s personality and her subconscious thoughts and desires. To be able to accomplish that I felt I really needed to know who she was. I ended up carrying a sketch diary with me on my free time to document what I was doing when I wasn’t doing anything in particular so that I could have a sense of what Rapunzel could be filling her days doing in her tower. So if I was putting my clothes away I would get out my sketchbook and draw Rapunzel hanging up her clothes in her room, and then I’d see that I was drawing while I was supposed to be doing chores which led me to an idea that Rapunzel would be constantly creating: if she had mending to do it would turn into a full-on craft project. Needless to say not much housework got done those few weeks of “research”!

Kirill: Your character and scene sketches are wonderfully expressive and exude a lot of vibrant warmth and energy. What does it feel to hand them to be transformed into precise mathematical models and how much (if any) of the original feel is lost in the process?

Claire: I’m honored if any of my sketches get handed off to be modeled! It is so rare to have your inspiration be taken all the way through to the finished product. As for the mural paintings, they weren’t really finished until they were mapped onto the CG model and lit. Once we saw them like that it all felt so much more real. It added another layer of believability to the character- as if Rapunzel had really spent all those years in her tower painting them.

Kirill: What do you think about the transition of the industry in general, and full-feature animation movies in particular, to the 3D world?

Claire: I feel really lucky to be apart of this time in animation. It feels like it is full of ripe ideas just ready to present themselves to the public. There are so many amazing things that are possible to do and very little of it has yet made it into a full-length feature film. I think we will start to see hybrids of 2D and CG animation and completely new styles and ways of animating that we have yet to conceive of coming out of the industry soon.

Kirill: “Tangled” has an amazing level of detail everywhere – tree leaves, grass blades, wall stones, pavement blocks, dresses and, of course, the magical hair. That leaves the characters’ faces as the only flat element lacking any level of realism. Is this related to the “uncanny valley” that has plagued movies such as “The Polar Express”, “Beowulf” and, to a much lessed degree, the Clu character in “Tron: Legacy”?

Claire: Yes, there was discussion about how naturalistic they wanted to make the characters. They ended up with a more stylized version for the sake of animation.

Kirill: Can you recommend a few of your all-time movie favorites? Have they influenced or shaped your artistic style?

Claire

Claire: Cinderella for the colors, composition, and story which are so magical. But I think the movie that has most inspired my visual development work on “Tangled” in particular was Sofia Coppola’s “Lost in Translation”. I loved how she spent time with the main character without having to get to a plot point right away. Everything I was doing in my sketch diary that I spoke of earlier was really inspired by watching Scarlett Johansen’s character just sit in her hotel room- you really start to feel like you could hear her inner thoughts even though nothing was really happening externally and no dialogue was being said. I’ve found I really love exploring a character’s private moments that may not necessarily be scripted in the movie but they make me believe in the character I am spending time working on. And I have seen that it helps me a lot when thinking about anything I would need to design for him/her: be it the character’s bedroom, costumes or even their paintings on the walls.

Kirill: What’s next for Claire Keane? Anything exciting you can share with us?

Claire: I am hoping someday to find the time to work on my own personal project. As for right now though, I’m having a lot of fun working with some wonderful people: Chris Buck (director of Tarzan and Surf’s Up) and Mike Giaimo (art director of Pocahontas) on a really fun and whimsical film. Mike has such a bold personal style and I am so excited to help get that style onto the screen.

And here again i would like to thank Claire Keane, not only for taking her time to answer my questions, but also for bringing us such a wonderful cinematographic experience. If it takes another six years for your next movie, my daughter and I will be waiting.

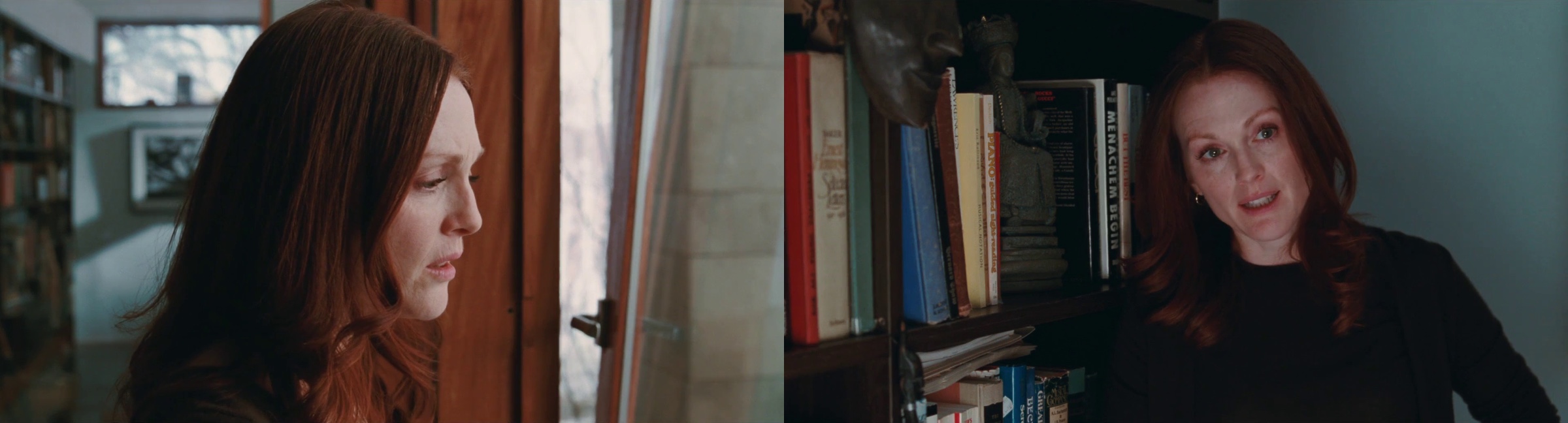

I happened to stumble upon “Chloe” almost by accident this week, and it was love at first sight. An erotic thriller drama starring Julianne Moore, Amanda Seyfried and Liam Neeson, it’s an exquisite visual treat that I couldn’t leave unattended. The opening sequence sets the intimate atmosphere with soft lights, smoked glass and the camera slowly panning across Amanda’s character gazing at herself in the mirror (seen above).

Glass, windows and mirrors are interwoven throughout the various scenes, from the first encounter between Amanda and Julianne in the bathroom to the Ravine House designed by Drew Mandel. As you follow the movie, note how this positions the viewer behind the characters as hidden observers, supporting the progressively increasing intimacy of the plot.

Background elements key off of the skin, hair and eye color of the two leading female characters and vary based on the scene mood. Here is the very first scene featuring Julianne – in the cold and sterile doctor’s office, with the steely green walls, cabinets and lamps keying off of her eyes, and the blurred chart complementing her hair and freckles:

Soft browns dominate the large open spaces in the house, perfectly framing the strong hair color and providing just a tinge of green and blue:

As Julianne’s suspicions grow, the costume colors become progressively more subdued, staying within a very narrow range or green-tinted beige and dark emerald. Here is the second encounter between her and Amanda – note the saturated red fire alarm box that highlights the inner tension of her character and the brown delivery truck behind the window:

The costume designer Debra Hansen provides a little insight into the morphing colors and textures:

There are shapes, colors and structures that are mirrored in the choice of clothing for the characters. On Chloe in particular you’ll find colors and patterns that are connected to the outside environment. For example the coat she wears in the greenhouse and the coat with the embroidered leaves both reflect her exterior surroundings. You’ll notice too, though it’s very subtle, that outfits for Catherine and Chloe begin to echo one another

As the two female characters become more involved, the movie spends a lot of time following their encounters. One of my favorite conversations is initially bathed in a large swath of neon blue washing in from the outside, highlighting the cool and somewhat distant mood of the encounter:

As the dialog becomes more intimate, the camera sweeps to the left, stopping slightly above Julianne’s right shoulder. Rich warm golden browns replace the cool blues, and the green leather becomes deeper and more saturated. Here, even though clearly Amanda commands the scene, i cannot stop looking at the background setting and how it frames the main character. From the wall paint color to the painting to the clothes and hair of the couple holding hands – simply perfect:

And here’s another example of the perfect blend of background elements – with steely greens and muted oranges playing off of the hair, skin, eyes and clothes of the foreground characters:

Cuing the audio track from the next scene is one of the most common ways to transition the viewer into the next scene. As the camera stays to exit the current setting, the audio switches to background noise or the few opening sentences of the next scene, followed by the mostly abrupt visual transition into the middle of the new setting. “Chloe” chooses a different strategy. With its slower visual pace, the transition has an intermediate stage where the camera lingers on the new surrounding environment, guiding the user into the new setting. Cafe Diplomatico is one of the main locations, and here it is in one of these intermediate transitions:

Soft browns spill into this scenery, from the pavement to the brick walls of the adjacent building. The attention to details is amazing considering the fact that these are public locations not fully controlled by the production crew. Here is one of my outside favorites, with the much cooler grays and turquoises that accentuate the ulterior motive behind Amanda’s manipulations:

The interior design of various locations follows the mood and tension levels between the characters – from the slate grays of the house to golden browns of the hotel room:

Phillip Barker is a man of many talents. Between writing and directing his own short films, he also works as the production designer for major movie productions. He’s graciously agreed to answer a few questions i had about “Chloe” in particular and on movie art and design in general.

Kirill: Tell us a little bit about yourself and how you got to work on “Chloe”

Phillip: I am a visual artist who has always been interested in film. I currently combine two careers, one as a production designer for feature films, and one as a visual artist who makes his own ‘art ‘ films and installations. Atom Egoyan saw an installation I had made in a gallery and expressed interest in working with me. We have been working together on most of his films since then. Our first collaboration was ‘Salome’, an opera he directed for the Canadian Opera Company where I designed all the multimedia projections, and the first film I designed for him was “The Sweet Hereafter”.

Kirill: Most of the scenes in the movie take place indoors. Have you used existing locations with slight interior tweaks, or was most of it built from scratch?

Phillip: I designed and built the third floor of Julianne Moore’s characters modern glass house. It had to seamlessly flow with the actual location. The set included the master bedroom, bathroom, David’s study, 2 staircases and a view to an 80′ long photo mural outside the windows. We also built the hotel bedroom and a few other sets. Sometimes we added to existing locations, for example we built a smaller greenhouse within the large greenhouse of Allen Gardens, Toronto.

Kirill: How much of the set design was influenced by eye color, hair color and skin tone of the main characters?

Phillip: We found neutral colours, and greens to look the best with Julianne’s and Amanda’s hair and skin tone.

Kirill: When Ann Rutherford told the producer David O. Selznick that he can save a lot of money by having the “Gone with the wind” actresses wear flannel petticoats under their hoop skirts, he replied that maybe the audience wouldn’t see them, but the actresses would know they weren’t silk. How important is it to create a complete set even if some parts of it are never seen by the audience?

Phillip: Sometimes I make things interesting for myself, the set dressers and the actors by accessorizing the sets beyond what is seen. For instance, in a main location we would sometimes fill drawers and cupboards with objects that would help define the background of the character. Pertinent books will be used on the shelves… these sort of things often become featured, and can provide the freedom to invent new scenes and to shoot spontaneously.

Kirill: You’re operating within the confines of the script, director’s artistic vision and, sometimes, specific external locations. Do you see this as a factor that limits your creative freedom, or rather a welcome challenge?

Phillip: I enjoy the challenge of working within boundaries. Because I write and direct my own films, often I get involved in the scripting process. I may suggest different locations that may tell the story better, or an action that could replace dialogue. Most people in film recognize the advantage of allowing ideas to flow in a collaborative way. Sharing ideas in the planning of the film is what I enjoy most about film making.

Through discussion I try to find visual language that becomes a coda for the film. Images of texture, colour, light and wardrobe are gathered specifically to the film. These images are put together in a book which is reproduced and distributed to the crew and cast. This “look book” becomes useful for specific references to style, period, but also just to inspire and remind ourselves during the shoot what we set out to do.

Kirill: Open space and cool glass surfaces surrounding the “Chloe” characters at home, soft rich colors and textures bathing the two actresses having an intimate conversation at a coffee shop – what is the importance of the scene setting and background elements in supporting the main story line?

Phillip: In “Chloe” glass became an obvious material to use whenever we could. Catherine lives in a house of glass and all that represents, the erotic voyeuristic nature of glass and windows, the way glass changes with extremes of cold and heat (like the story and the setting), and the way glass reacts when we touch it. It’s like an invisible skin.

Kirill: Computer-generated environments traditionally seen in sci-fi movies are becoming a more mainstream production tool. With the ever increasing sophistication and progressively more powerful capabilities of modeling and rendering software, do you see the filed of physical production design endangered by this trend in the next couple of decades?

Phillip: I enjoy the use of CGI in extending and enhancing real sets. If the film needs to be naturalistic, care must be taken not to overdo CGI and to build into computer generated scenes small flaws that you may experience when shooting something real. I often oversee the CGI work to make sure it fits.

Kirill: And on a perhaps related note, what are your thoughts on the growing presence of 3D productions in feature films?

Phillip: Film has a very short history and the way we read and interpret film is constantly changing. Technological breakthroughs and advances in film production very quickly become accepted, as the audience learn and adapts to new ways of looking. Interestingly, the older technologies remind us of the past and therefore possess a power of nostalgia. Technology becomes our history, it’s how we define ourselves and helps tell our personal story. Our storytelling, and our fascination with light is timeless.

And here I would like to thank Phillip for his outstanding work on the movie and encourage my visitors to watch it and keep an eye not only on the plot, but on the visual surroundings.

When i sat down to watch “Unstoppable“, the new movie by Tony Scott featuring Denzel Washington, Chris Pine and Rosario Dawson, i was immediately drawn into the heavy industrial visual atmosphere of the movie. The opening sequence delves into what looks like a blue collar neighbourhood, with dominating turquoise color and a few splashes of yellows and browns:

When the two leading characters are introduced, the color palette becomes a little richer with tinges of green, still remaining in the predominantly cool and desaturated band:

The vast majority of outside sequences feature railroads and trains – static at the beginning as shown in the next image. Note the color variation between the different models, balanced by the consistent pinstripe pattern that brings yellows and oranges into the scene saturated with blues, turquoises and greens of the trains and surrounding forest:

Once the characters get on the train, the camera switches between inside and outside shots, rarely placing the two together in the same frame. The outside shots are taken close to the cabin windows, with blurry rain drops creating attractive secondary textures that blend well with the carefully crafted interior design:

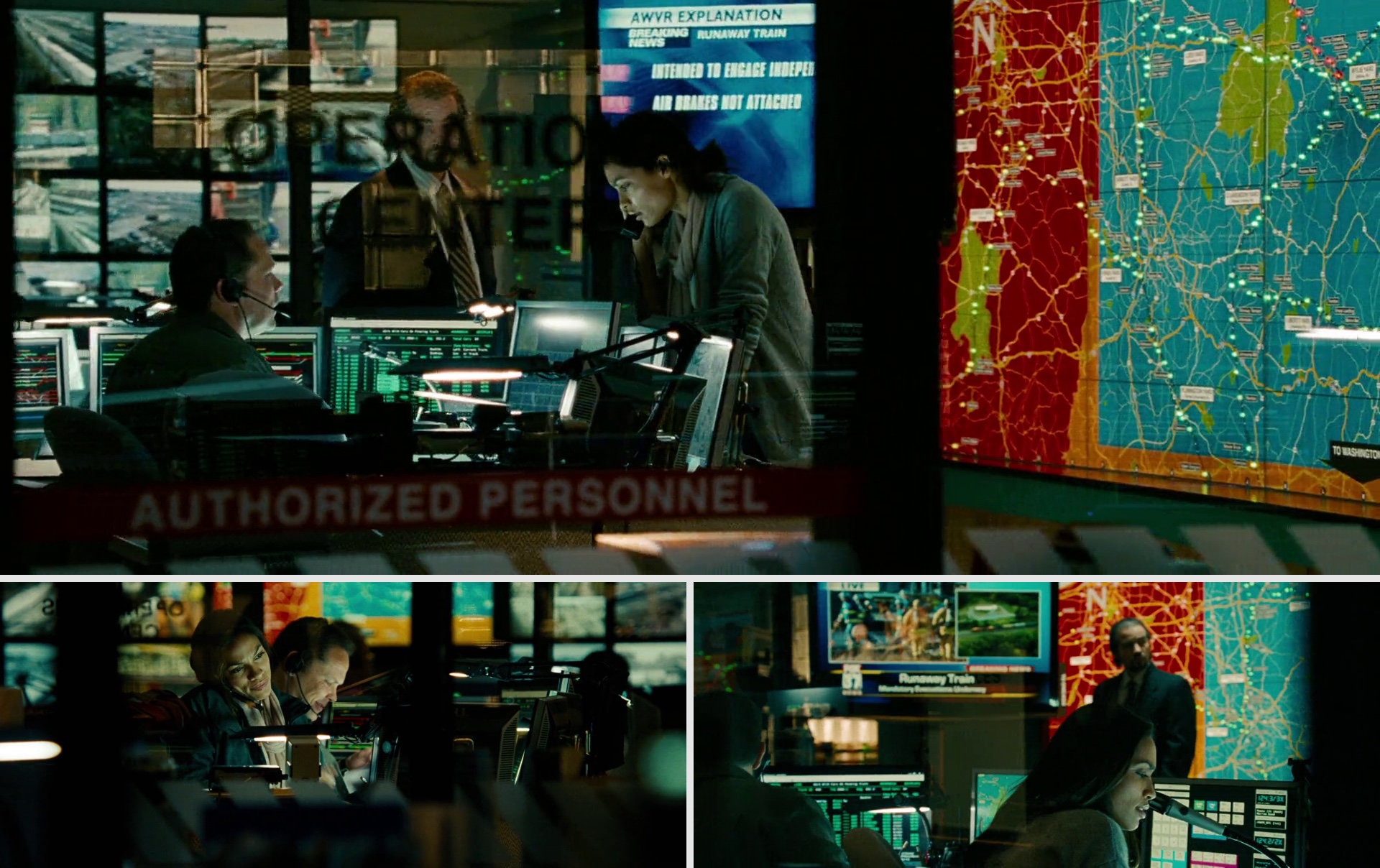

Once the train gets moving, it provides a fast changing dynamic scene. The third lead character played by Rosario Dawson is placed into a control room, leaving her to rely on radio communication and telemetry systems to collect information. Here is her character on the backdrop of an oversized route map. The map uses a variation of each primary color – red, blue and green, all shifted and desaturated to serve as a supporting visual element:

While most of the scenes in the control room are dominated by close-up shots of Rosario, the camera switches to the supporting characters to add some depth and variety. These characters are often filmed from a greater distance that highlights their secondary role and adds more perceived space to the location itself. Here, note the multitude of screens, each deriving from the main color palette of sand yellow, olive green, turquoise and brick red:

Extending the through-the-glass shots mentioned above, the camera moves quite freely around the control room, crossing boundaries of the rooms, open spaces and glass cubes. Not only this adds a lot of dynamism to this closed environment, it also places the viewer as an outside observer in a setting not accessible to general public. The next image illustrates this perfectly – the glass wall extends two thirds into the frame, adding an element of “observing with being noticed” – with the slightly blurred texts further highlighting the access restrictions:

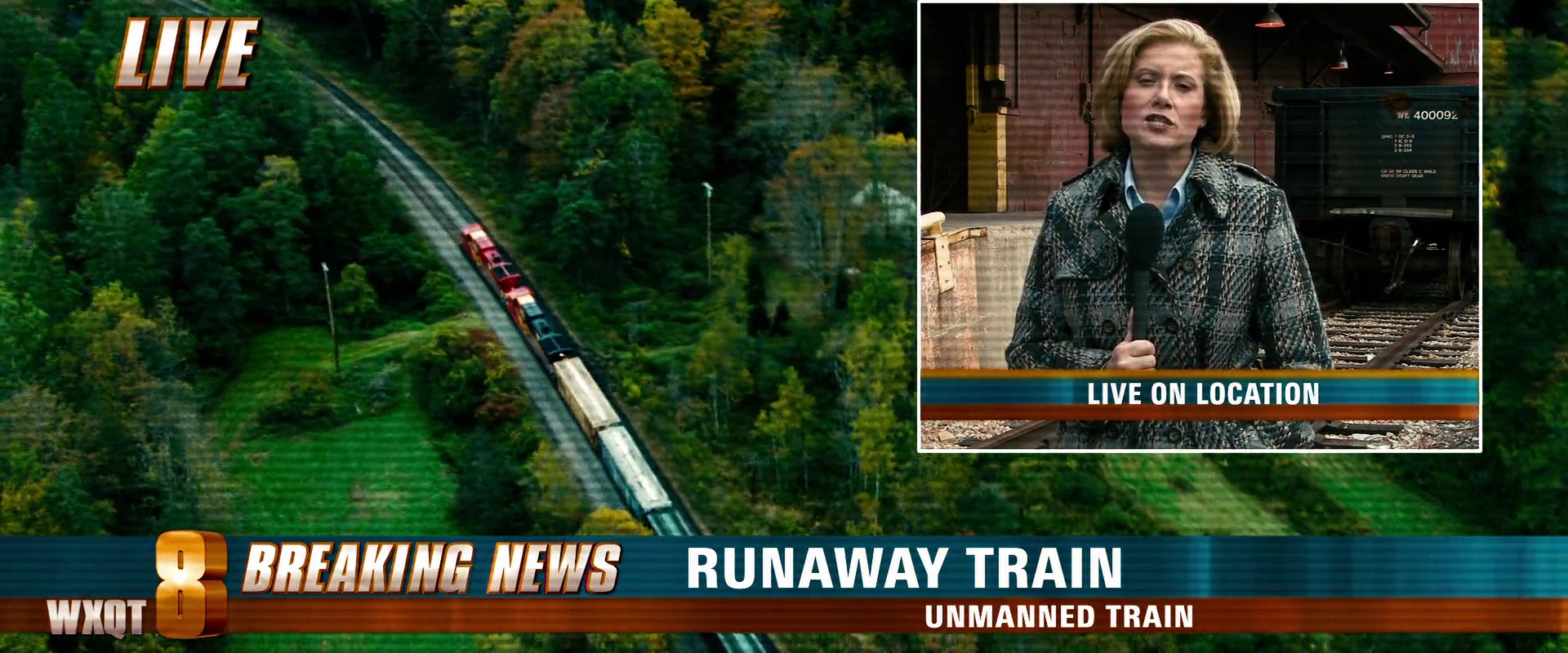

The tension around the runaway train is further reinforced by cutting to live TV feed from a local station. For an extra dramatic effect, this starts early on and is weaved into the interaction between three main characters. Most TV scenes are live-“shot” from the helicopters, adding large swaths of rich green forestry. This is balanced by the oranges, yellows and turquoises taken from the engine yard and control room monitors – further anchoring the cool color palette of the entire movie:

Some shots feature close ups of the locomotive. Bright oranges and reds of the exterior paint are supported by the emergency vehicles, patrol helicopters and police car flash lights. The next image shows a scene as filmed by the low-flying TV station helicopter. The camera is pointing forward, and rain drops add extra authenticity to the view, creating large blurred spots and causing nice refraction halos:

As the TV cameras follow the train along its winding path, the aerial shots are intertwined with stationary cameras – highlighting the opportunity that the ground crews had to mobilize the large vans. As before, such images frame the moving trains with lush forest scenery and standby emergency crews – note the red and yellows of the locomotive match the colors of the firefighter uniforms:

And yet one more example of a complex scene that combines two overlapping feeds. The oranges, yellows and turquoises of the TV station identity define the visuals of the feeds as well – note the sand yellow hair color of the reporter, combined with her light blue blouse and a glimpse of the roof flash lights on the police car behind her:

And this is, perhaps, my favorite shot:

There are three main elements here, all “moving” in a perfect visual unison. The news strip at the bottom, the train cars and the hovering helicopter all use the same color transitions – deep turquoise on the right and yellow orange on the left. This is a very strong palette that serves as a major backbone for the entire movie.

It is my absolute delight that Drew Boughton, one of the key people responsible for the movie visuals has agreed to answer a few questions about his work on the movie and the industry in general.

Kirill: Tell us a little bit about yourself.

Kirill: Tell us a little bit about yourself.

Drew: My name is Drew Boughton. I am a Production Designer and live in Los Angeles with my wife Linda Boughton who is a Fine Art Painter.

Kirill: Production designer, art director, set director – all sound vaguely the same for people not closely involved with the industry. Can you explain the creative process behind the movie visuals?

Drew: Yes, a Production Designer is the key visual collaborator on the look of the movie working with the director prior to the involvement of the DP or Director of Photography. On “Unstoppable” the Production Designer was Chris Seagers. The Production designer is responsible for everything that is “seen” on camera. The selection of locations, colors and feel are all shepherded by the production designer in the prep process of the movie. The Director approves or makes changes as he or she sees fit.

The Art Director is the person who implements the design of the movie. This is done through directing and supervising the creation of drawings, the organizing of construction, paint and set decorating crews. This is generally speaking a “hands on” artistic job. I was one of three Art Directors on the film. Dawn Swiderski and Julian Ashby shared that title and responsibility with me.

Kirill: Looking at your career as an art director, you do roughly one movie a year over the last ten years. Would it be correct to say that your part starts long before the actual filming and ends long after the actors have moved on to their next movie?

Drew: My job starts 3-4 months before filming begins. And generally ends after all principal photography is done.

Kirill: The full crew page for “Unstoppable” lists well over a hundred creative artists in the art and visual effects departments – and you have even more for the upcoming “Pirates of the Carribean”. How do you make sure that the end product has a consistent look that supports the main storyline, and stays “out of the way” as much as possible?

Drew: There are a lot of people involved in managing that including the producers and the DOP (director of photography) who is principally in charge of capturing everything on film in a graceful and beautiful way that is consistent with the storyline etc. Of course the real person who guides all of this is the Director whose vision is being served by all the people around them.

Drew and RZA on the set of the upcoming “The Man with the Iron Fists” movie that stars Russell Crowe, Lucy Liu and Pam Grier.

Kirill: What is your ideal level of movie director’s involvement with the art department? Do you prefer getting a high-level description of the visual mood and a cart blanche control over the entire set, or perhaps a closer collaboration throughout the various production stages?

Drew: The ideal level depends really on the Director. It is not so much a matter of preference. The thing is that an Art Department is a service based thing. We offer a specific service to the Director of a film. If that Director wants to be involved in reviewing every sketch or drawing the Art Department makes that is great with me. If the Director does not want to be “bothered” with seeing every drawing that is cool too. Although it can make for surprises on set which sometimes are a little uncomfortable. It just depends on the person.

Kirill: Most of the outside scenes in the movie feature heavily tinted turquoise palette. How much of this was done with lens filters, and how much was left to the post-production stage?

Drew: Tony Scott is widely respected (and emulated) in the Film industry for his unique photographic look. His films are considered masterpieces of cinematography and he has the experince to choose certain types of cameras and equipment with a desired look in mind before the film is ever produced. Most of the color comes from that knowledge of photography and a final “tweak” comes in post production digitally

Kirill: A lot of outside scenes were shot on rail yards and bridges. How much control over the production design of such scenes are you willing to cede to external parties?

Drew: We shot in existing locations primarilly which were stunning. So we have to give it for those cool places. The things we brought to the locations were all of our trains which were painted by us. We painted all the pricipal locomotives and train cars specifically to the instructions of Director Tony Scott and Production Designer Chris Seagers. As you watch the movie much of what you see is the trains themselves.

Kirill: The main control room (where Rosario Dawson spends the majority of the movie) is my favorite location. How much work goes into creating such a detailed indoors environment?

Drew: A tremendous amount went into that. That was a built set on stage in Pittsburgh. The giant illuminated map was created from scratch and animated to assist in telling the story.

Kirill: The transition from black-and-white movie to full color ones midway through the 20th century took a few good decades. Are we witnessing the beginning of a similarly lengthy and inexorable transition to productions that are not only augmented, but also predominantly produced in virtual CGI / VFX environments?

Drew: I don’t know of anyone on the planent who could honestly answer that question. The thing is do you want to watch a real Actor acting? If you do it will be hard to replace that person with a 3D model. As for the enviornments it is a bit of the same question: real actors in fake environments are “fake” to me personally so I tend not to like those movies.

Kirill: On a related note. The last two Oscar awards for art direction went to “Avatar” and “Alice in Wonderland” – both blurring the lines between real and imaginary worlds, fusing real actors and computer-generated characters in lush otherworldly environments generated on massive render farms. Do you see this as a passing fad that is “rewarding” the technical advancements, or a more steady trend away from traditional production and art design?

Drew: I think that both of those films are excellent and both feature traditional Production Design. The distinction is the implementation of the design. Sometimes is constructed in real space as the Avatar lab was and sometimes it is in 3D depending on the practical needs of the script.

I do not see any steady trend one way or the other. I see improvements in technology that film makers use to tell a story. To me it is more a question of what story the film maker wants to tell. If it is more films about future science fiction worlds than thats one answer. But sometimes a film maker wants to heave real drama based in real places as “Unstoppable” was. These were real trains with real stunts and very minor VFX augmentation. Which is why it is so gripping.

And here I would like to thank Drew Boughton once again for this wonderful opportunity, and his great work on the movie. I want to leave you with two more images. The one above is another shot from the TV feed – note how the train movement is conveyed by blurring the surrounding scenery while still keeping the cargo details in focus. And, if you haven’t noticed up until now, look at the translucent horizontal stripes applied on all TV scenes, helping to separate them from the rest of the sequences.

And here is the beautiful Rosario Dawson framed by the blurred wall monitor and muted steel blues and greens:

I hope you enjoy the movie visuals as much as I did.

I must confess that when I first saw “The American” in the movie theater last fall, I was completely blown away by the exquisite visual treatment that permeates every single frame. Set in rustic Italy, the camera follows George Clooney that plays a craftsman that constructs a custom weapon for the female assassin played by Thekla Reuten.

Daylight outdoors scenes combine pale verdant greens and light sky blues into a perfect backdrop that frames and keeps the focus on the main characters, while still placing them slightly off center to convey the open space around them:

Clooney’s character spends a lot of time driving between different towns, with the camera placement forgoing the usual just-inside-the-front-shield position. Instead, the shooting is done mostly from outside the car, with a couple of great reflection shots that combine character faces with the outside scenery:

One particularly attractive shot shows the car traveling in moonlight on a winding road, with the headlights piercing the eerie emerald fog creeping along the hill side:

My favorite scene of the movie lasts less than a minute. Clooney goes to the train station to meet Reuten. The visual balance, colors and angle switches in this scene are simply fantastic. Here, the camera shoots from behind his left shoulder, keeping his blurred profile in frame and catching train’s reflection in the glass:

And this is shot from a slightly different angle, highlighting her confident pose and a deserted station:

I’m truly honored to have the cinematographer Martin Ruhe finding a few moments in his busy schedule to answer a few questions i had about his work on the movie and the industry in general.

Kirill: Tell us a little bit about yourself

Martin: I’m a german DP [director of photography] living in Berlin. I’ve done 6 films by now, hundreds of commercials and hundreds of music videos. That’s how i started with music videos 17 years ago. My first feature was a not a nice experience, so i waited a long time until Anton Corbijn asked me to do “Control” with him. I like the mixture of different projects and being able to wait for the right film to do by doing shorter projects. Plus it can be a good training in terms of gear, speed, working in different countries…

Corbijn and Ruhe on the set of “The American”

Kirill: Cinematography does not get as much limelight as directing, scripting, costume design or visual effects. Do you like working “behind the scenes”?

Martin: It’s OK because people who know and work in the industry understand what cinematographers do and appreciate it very much. Plus smaller films like “Control” get seen by a lot of people in the field, even though it’s not clear that they have an impact on the broad public. I was also lucky to get a lot of press attention on the cinematography on “The American”, “Harry Brown” and “Control”.

Kirill: How much creative freedom do you usually get, over specific scenes as well as the overall visual atmosphere of the movies you’re working on?

Martin: It’s always teamwork. I do not have to have a lot of freedom in how to do things. For me it has to come from within the story – what’s the right mood what does it feel like. It’s great to discover this together with the director. I am usually much involved and also like to mention things in the script if they do not make sense. In the past my directors trusted me a lot and it was a great collaboration. It’s nice to tell a story together.

Kirill: What is more frustrating, working with fickle weather conditions of unpredictable actors?

Martin: The weather i would think – there’s nothing you can do about it. On “The American” we started shooting in september in Abruzzo. We spent the first days of shooting in a village in the valley; it was like a very hot summer. When we finished in the mountains it was september and we had snow on some days. It was very tough also because all the trees had changed their color or lost their leaves, so maintaining the continuity was difficult. Here’s another example – Castel Del Monte lies 1600 meters above the sea level. You start shooting a scene in pure sunlight and then this cloud comes along and then you sit in it for hours (meaning in real heavy fog). What do you do? Do you start the scene again or wait or… The chase sequence and some other night scenes during that week are other example for bad weather. It was raining all night and at the end of the week the ground was freezing which was of course very tricky for cars chasing each other but also exhausting on crew and gear.

If an actor is unpredictable that’s OK. Most of the time, if it comes from within the story i think it’s cool because they can have a very different take on things. If it’s about insecurity then you have to earn their trust and protect them. For actors it can be difficult because unless they’re on set every day it might be hard for them to be fully part of it. There’s so much they don’t see happening and they don’t have a lot of say about things are done. Fortunately, the bigger stars i have been working with were trusting and relaxed about how we did things.

Kirill: Given the choice, would you prefer shooting as many takes as needed, or leave some of the visuals to the post-production phase?

Martin: Whatever you can do on set i think should be done there. But of course with post-production possibilities and schedules these days you always have to juggle and balance these things. On “The Countess” we used footage of Julie Delpy from a movie called “Homo Faber” from more than twenty years ago. We copied the lighting, tried to work out which lenses they used, Julie acted by a monitor to match the movement of the old scene and it worked. The effect was that in the final scene we tell how the countess gets married as a young woman, and we really see the young face of her. It was great because there’s also the way where you work and paint on the face in the post so you make a face of an actor of today younger. But it’s different – yes, there’s less wrinkles and all that but a face changes its shape so much and there’s more detail to it than a pure post solution can do. As far as i know we were the first ones to go this way.

Kirill: With advances in 3D shooting technology, we should expect this equipment to become available to even lower-budget productions in the next few years. Are you interested in exploring these new capabilities?

Martin: It’s OK. To be honest i have not seen a film yet where it has added that much to the story that i think it’s worth it. However, I am curious about the new Wenders movie about Pina Bausch and the art of her dance. But in general it seems to work well in animated films and not so much in the reality. It also seems to come from TV manufacturers trying to sell new products – rather than from movie goers missing anything. So it will be interesting whether that’s going to succeed. At the moment productions are very expensive, usually much longer and not too many of them have been that successful. Let’s see.

Kirill: The movie-going experience hasn’t changed much in the last few decades, with only incremental improvements in sound and picture quality. Do you foresee big changes in the decades to come?

Martin: Interesting question. I think the image on screen has gotten much better over the last decades, and the skills of crew are getting much better all over the place because also there’s so much more training available. And what about the 3D you mentioned in your question before? That’s a big change again, no?

But right now more and more films are produced on digital cameras. Having used them myself on commercials and two movies (“Harry Brown”, “Page Eight”) i can assure you that the best image quality is still on film. The new technology is getting better but the 35mm image is superior to all, yet it seems that more and more productions go digital. On films like “The Social Network” the decision is unlikely to have been about costs and there’s a lot of marketing going on for the new media; everybody seems to want to use the new technology but the decision is more and more not based on the cinematographers choice of what to use or on what’s the best quality. That seems weired to me.

Kirill: Among the movies you’ve worked on, what was your favorite location, and what would be the dream location if you were free to choose one?

Martin: There are so many beautiful places around so it’s hard to me to choose one… It probably would be in Italy! It’s such a beautiful country in every region. Definitely Abruzzo was the most beautiful location i visited for a film.

Kirill: At least in US, we’re constantly being bombarded by ads and trailers for big-budget movies. Can you recommend a few of your personal favorites that aren’t necessarily blockbusters?

Martin: “A Prophet” (french movie), “Let The Right One In” (swedish movie). I liked “Black Swan” and am very curious to see “Never Let Me Go“.

Kirill: Any exciting new projects that you’re working on?

Martin: I am reading some scripts but nothing is decided yet. I would love to do a movie in the states next. A good one.

And here i want to thank Martin once again for this great opportunity. Finally, if the train station sequence is my favorite one, then the night-time shots of the local coffee place are very close. Two dominant colors, golden brown and soft turquoise seems to spill into each other, with interior reflections superimposed on the street and wooden panels that match the color of the street lights. Also note how the two colors seem to “fight” over the skin tones of the actors:

![]() Claire: I grew up in southern California until the age of 16 when my family decided to move to France for a year. After one year our family loved Paris so much we stayed many years thereafter. After graduating from the American School of Paris I went to Parsons School of Design in Paris for one year thinking I would like to go into fashion design but soon enrolled in the Ecole Superieure D’arts Graphiques realizing that illustrating and drawing was really my passion. In my fifth year at ESAG, I chose to write and illustrate a fairytale book for my thesis project. It wasn’t until then that I realized how much I loved the development phase of a project. When “Tangled” came to the point where they needed to bring people on to develop Rapunzel’s world I was ready to go with my thesis project in hand as my portfolio.

Claire: I grew up in southern California until the age of 16 when my family decided to move to France for a year. After one year our family loved Paris so much we stayed many years thereafter. After graduating from the American School of Paris I went to Parsons School of Design in Paris for one year thinking I would like to go into fashion design but soon enrolled in the Ecole Superieure D’arts Graphiques realizing that illustrating and drawing was really my passion. In my fifth year at ESAG, I chose to write and illustrate a fairytale book for my thesis project. It wasn’t until then that I realized how much I loved the development phase of a project. When “Tangled” came to the point where they needed to bring people on to develop Rapunzel’s world I was ready to go with my thesis project in hand as my portfolio.![]()

![]()

![]()