I’m not going to take credit for the story, nor would I claim a perfect analogy. But here goes.

Imagine you’re in a room with ten screaming babies. As all of them are screaming at the top of their lungs, you start feeding them one by one. You’re done with one, and there are nine screaming babies left. Some time passes and you’re done with another one, and there are eight screaming babies left. Some time passes and you’re done with another one, and there are seven screaming babies left. And it doesn’t feel like you’re making any kind of progress because as long as there is at least one baby screaming, you can’t get any peace.

That’s how it can feel to be a programmer on any reasonably sized project. Where screaming babies are bugs in your incoming queue. They never stop demanding your attention, and they never stop screaming at you. Unless you make peace.

If there’s one axiom of software development that I hold inviolable, it’s that there will always be bugs. You can surround yourself with a bunch of processes, or do extensive code reviews and endless testing rounds. But the bugs will always be there. If anybody tells you that their code doesn’t have bugs, just shrug and walk away. They have no idea what they’re talking about.

Make peace with the simple fact that the code you’re shipping today has bugs.

Some bugs are scary. You need to tackle them. Some bugs, on the other hand, are these little tiny things that simply don’t matter. The problem with most (probably all but I haven’t tried them all) bug trackers is that the scary bugs in your queue look exactly the same as the tiny bugs. Most of the time the only difference is going to be in the single digit in the priority column. Or maybe the scary bugs will have light red background across the entire row. Or maybe the tiny bugs will use lighter text color. But they probably won’t.

And so you stare at your queue and you feel that you just can’t win. No matter how much effort you throw at that queue, as long as you’re not at zero bugs, they are screaming at you. And every time you fix a bug, you touch your code base. That’s another bug that you’ve just added. And every time you fix a bug, you get assigned a couple more.

Make peace that not all bugs are created equal.

Zero Bug Bounce is a fiction that some people invented to make peace for themselves and to create an illusion that they are in control. So at some point in the cycle everybody looks at the pages upon pages of bugs in your project queue, frowns and then mass-migrates a bunch of bugs to the next release. And to the next one. And to the next one. And at some point some bugs have been bumped out so many times that you might as well ask yourself some very simple questions. Do those bugs matter? Do they deserve to be in the queue at all?

Make peace that not all bugs are actually bugs.

Sometimes a feature that you’ve added to your product just doesn’t work out. It doesn’t get the traction you’ve expected. Or it’s not playing well with some other features that you’ve added afterwards. Or you’re not even sure how much traction it’s getting because you forgot to add logging, and there’s nobody on the team who actually cares about this feature after the guy who did it left the team and you’re in the middle of the big redesign of the entire app and why should you even be bothered spending extra time on that feature. Phew, that was a bit too specific.

And of course there will always be somebody who used that feature. And now that you’ve taken that toy away from them, they are screaming at the top of their lungs. And you cave in and bring that feature back. Well, in theory at least. But it’s been redesigned to fit into the new visual language of the platform. And now somebody else is screaming at you because you’ve changed things. All they want is just a teeny tiny switch in the settings that leaves things they way they used to be. Sure, they want new features, as long as they look exactly like the old features. But that’s a topic for another day.

Make peace that your work is never done. That if you want your work to be seen, you have to ship. Make peace that the work you ship will have bugs. Take pride in things that work. Develop a sense to know scary bugs from fluff. And develop a thick skin to ignore the screaming.

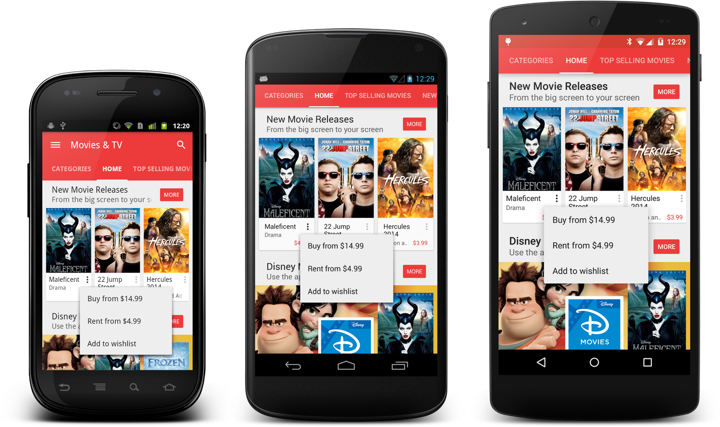

One of the more useful things that was “graduated” from the internal package in the latest drop of support libraries is ListPopupWindow.

No more need to try and emulate the look and feel of a popup window with a custom styled and positioned dialog for older platform releases.

Use R.layout.abc_popup_menu_item_layout for platform-consistent appearance (text style, margins, regular / ripple highlights) in your list adapter. Then set it with ListPopupWindow.setAdapter, optionally register a dismiss listener (note how the overflow dots for the “active” popup are darker), set anchor view for properly positioning the popup, compute the content width based on the content of your list, optionally mark it as modal so that it can be dismissed by tapping outside and don’t forget to call show().

With a bit more emphasis on content recommended by your friends, we wanted to make people avatars in Play Store more visually pleasing. In our previous release the avatars were round with a thin translucent grey outline, and in our latest release the visuals are a bit more polished. There’s a white ring surrounding the avatar, and an offset drop shadow, with both of these scaling to match the overall size of the avatar. Let’s talk more about the specifics.

The avatars themselves are fetched from the network, which gives us a square – and sometimes rectangular – source image. Our first step is to create a normalized square image based on the target dimensions on the screen. That normalized image preserves the source aspect ratio, upscaling the source if necessary to fill at least one dimension edge-to-edge and filling the second dimension with white pixels (taking care of non-square sources). This is done with Canvas.drawBitmap that takes a source and destination rectangles as the parameters.

The next step is to compute the pixel size of the ring outline and the drop shadow. The ring outline starts at 1dip and is capped at 4dips, while the drop shadow starts at 2dips and is capped at 3dips. The actual size is determined based on the avatar size, setting the cap at 96x96dips (based on our current design metrics). This results in visuals that scale with the avatar size (seen below), while still capping the ring and drop shadow to not be too big for larger avatars.

Now it’s time to take a look at the avatar layers. We have the avatar itself cropped to a circular shape, the ring outline and the drop shadow. In our first implementation pass we used Paint.setShadowLayer to combine the last two together into a single Canvas operation. We first painted the white ring, and then the avatar itself (since the drop shadow extends to both sides of the path, and we didn’t want the shadow to be visible on top of the “inner” image). However, the runtime performance of shadow layer was not very satisfactory. It took about 2.5ms to draw a single outline, and when we had a few avatars on the screen, the numbers started adding up.

Instead, we’re doing three separate layers.

First, we draw the drop shadow as Canvas.drawOval with a single translucent grey color. We use Paint.setStrokeWidth to set the interpolated drop shadow size, and Paint.setColor to set the interpolated drop shadow color (for larger shadows we use more translucency to keep the same overall shadow “weight” across different avatar sizes).

Second, we draw the avatar itself. We create a BitmapShader with the normalized square avatar source and TileMode.CLAMP and set it with Paint.setShader. Using that Paint object on a Canvas.drawRoundRect call results in the circular crop of the source image. There’s some extra bookkeeping to make sure that we’re scaling down the normalized source to make the white ring outline external to the image, not losing the few top/bottom/left/right pixels. This can be done with a combination Canvas.scale and Canvas.translate operations to keep the scaled-down avatar centered on canvas.

Third, we draw the ring outline as Canvas.drawOval with opaque white color. We use Paint.setStrokeWidth to set the interpolated ring outline size.

There’s a bunch of small objects used for the custom drawing operations, usually involving a mix of Paint and Rect ones. It’s recommended to create them once at the class level, initializing as much of the state as you can in your constructor. Then, during the actual transformation / draw operations that can happen multiple times during the layout / render passes, only set those fields that are dynamic (size / color). This way you won’t be creating transient objects which are discarded after they’re used – saving yourself from unexpected GC pauses in the middle of your rendering. Also try to use Canvas operations (transforms, scaling) instead of creating intermediate Bitmap objects. And measure every step to make sure that you’re not using operations that are too expensive.

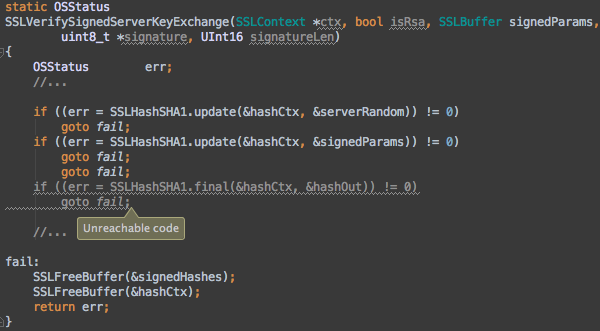

If only they used code guidelines that mandated braces around all blocks. If only they had unit test for this module. If only they had better static analysis tools. If only they had better code review policies.

There’s a lot of hand waving going around in the last couple of days, with everybody smugly asserting (or at least implying to assert) that they would never, in a million years, have made such a stupid mistake. And that’s what it is. Plain and simple. A stupid mistake. With very serious implications that reach into hundreds of millions of devices.

Except that stupid mistakes happen. To everybody. Unless you don’t write code. And if you write code and you really truly believe that you are not capable or making a mistake such as this… Boy, do I have a bridge to sell you.

Which brings me to my (almost) favorite thing in the world. Smugly asserting that I knew better than them and quoting myself:

My own personal take on this is that interacting with computers is too damn hard. Even given that I write software for a living. Computers are just too unforgiving. Too unforgiving when they are given “improperly” formatted input. And way too unforgiving when they are given properly formatted input which leads to an unintentionally destructive output. The way I’d like to see that change is to have it be more “human” on both sides. Understand both the imperfections of the way human beings form their thoughts and intent, and the potential consequences of that intent.

Do I have a solution for this issue? Are you f#$%^ng kidding me? Of course I don’t. But it kills me to realize that after all these decades we are still living in a stone age of human-computer interaction. An age when we have to be incredibly precise in how we’re supposed to tell the computers what to do, and yet to have such incredibly primitive tools that do not protect us from our own human frailty.

![]()