In the last few years her career spanned such a variety of productions as “Gangster Squad”, “Speed Racer”, “Immortals”, “Terminator Salvation” and “Avatar”, taking on roles as diverse as painter, compositor, designer, animator and supervisor. Most recently, after having joined Cantina Creative, she was the visual effects [VFX] supervisor on “Iron Man 3” and “Hunger Games: Mockingjay – Part I”. It gives me great pleasure to welcome the multi-talented Venti Hristova to the ongoing series of interviews on fantasy user interfaces.

In this interview Venti talks about the different roles she took on since she joined the industry, the spectacular magic of visual effects and the ongoing evolution of tools and artistic capabilities in the field, how “done” or “not done” is the HUD interface in Ironman mask, the role of VFX supervisor on blockbuster sci-fi productions and her work on the variety of screens in “Mockingjay”.

Kirill: Please tell us about yourself and your professional path so far.

Venti: My name is Venti Hristova. I was born in Bulgaria, I spent my childhood in England and I have been in LA for the past 18 years. My professional path has been paved by two people: the first is my dad, Lubo Hristov.

He started as a traditional animator and background artist in Bulgaria. Later he moved us to England where he became VFX Art Director at Cinesite London. After almost a decade in England he transferred us to Los Angeles. Soon after moving to LA, he founded a boutique Matte Painting company- Christov Effects and Design. Within the past two years my dad moved yet again; this time to Singapore as Art Director for ILM.

I studied illustration at Art Center College of Design and in my graduating year my dad took me to Berlin to work on set with him in designing the digital environments for Speed Racer. That was my introduction into the world of feature films and VFX. In Berlin I met the second most influential person in my professional life, Stephen Lawes.

Stephen is the co-owner of Cantina Creative, a VFX and motion graphics company based in Culver City. When I met Stephen, he introduced me to After Effects and animation and my life has not been the same since. Shortly after graduating from Art Center, Stephen hired me to design and animate graphics for Terminator Salvation at Pixel Liberation Front. Since then I worked my way from animator, designer, compositor to VFX supervisor.

Stills from short film “Gumdrop”. Art direction and animation by Venti Hristova.

Kirill: What drew you into the movie industry? If you go back to the time when you just started on your first feature film productions and some of the expectations that you had, how close (or far) has the reality of working in the industry turned out to be?

Venti: I guess you could say I was grandfathered into the industry through my dad. I was surrounded with his experiences on dozens of prestigious films and it was largely inevitable to become a part of the movie sphere in some capacity. I very much enjoyed matte painting and environment designing and after meeting Stephen Lawes I realized that I thoroughly enjoy animating motion graphics.

Kirill: What was it like to “lift a veil” on the magic of cinema and special / visual effects and see how much work is involved in making that magic happen?

Venti: I would have to say that VFX in itself is a pretty spectacular sort of movie magic that the average viewer is deprived from experiencing. I think that working in VFX is one of the more exciting aspects of the film industry these days because it encompasses such a huge part of the whole film production process from pre-production all the way through post.

Kirill: You’ve had a variety of roles such as matte painter, compositor, animator on production such as Gangster Squad, Immortals and Terminator Salvation. What are your thoughts on the evolving capabilities of digital tools at your disposal, and what they let you offer to the producers and the directors as the years go by?

Venti: The world of VFX tools in constantly evolving, so much so that you can get overwhelmed with the amount of new technologies. There is something very purist and “old-school” with relying primarily on one software such as my commitment to AE, however, the magic opportunities that open up with integrating C4D with AE or even Nuke and exploring the amazing universe of new plugins for blurs, glows, time-remaps, etc. is phenomenal. Looking back at the tools we were using on Terminator Salvation vs the tools we used for Iron Man 3, technology has made leaps and bounds and we have abused all their new flashy updates. At this point I can safely say there are no limits to what we can offer clients and that is a fantastic place to be professionally.

Stills from short film “Gumdrop”. Art direction and animation by Venti Hristova.

Kirill: Is everything can be done and it’s only the matter of time and budget? Do you feel that the demand from the production side is outpacing the evolution of tools’ capabilities?

Venti: I don’t think that production has outpaced VFX tools and capabilities. In the time of ILM and Weta the opportunities for VFX are limitless. There really is little that cannot be done at this point.

Kirill: Back in 2004 “Sky Captain and the World of Tomorrow” was shot entirely on green screen, with all the sets created digitally in post-production. In your opinion, is this something that you want to work towards, to be able to offer complete world creation for any kind of a film production?

Venti: Ironically, Stephen Lawes was an integral part of the creation of Sky Captain and the World of Tomorrow, and we met on a movie that similarly relied almost exclusively on green screens/ VFX environments, Speed Racer, so in that regard I have experienced working on that kind of production. That being said, I recently worked on the set of Mockingjay Part 1+2 and it was an incredible experience to walk on a fantastically production designed set with spectacular detail and construction. I think I prefer to work on movies with a healthy balance of movie practical realism and VFX movie magic.

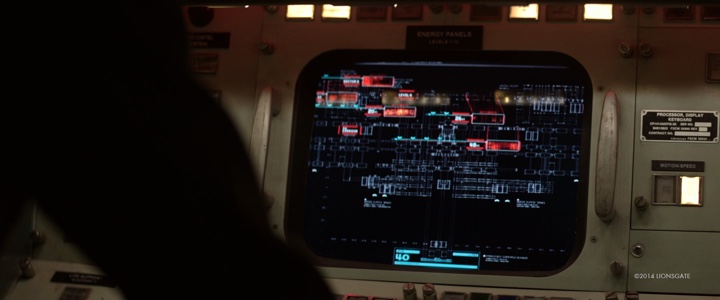

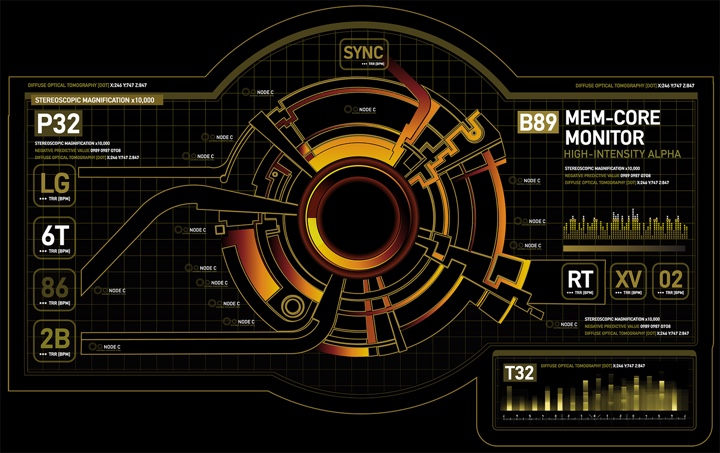

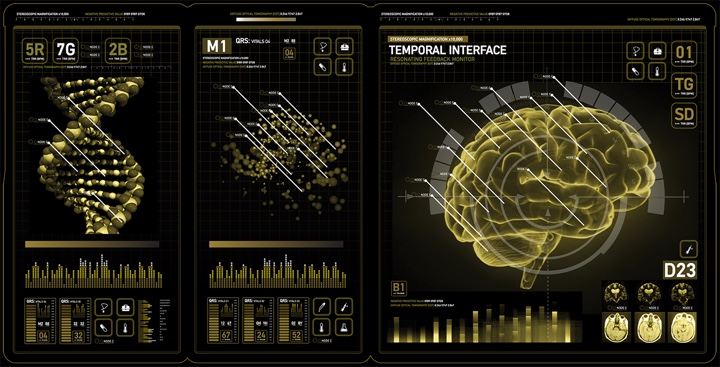

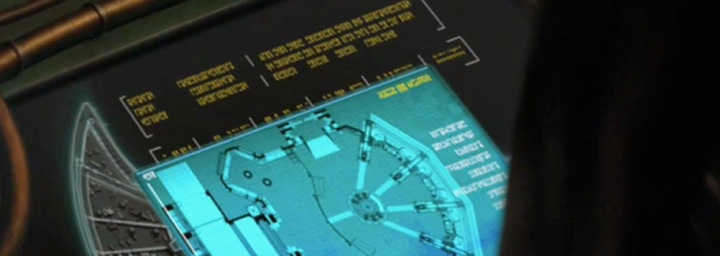

Screen graphics on “The Hunger Games: Mockingjay – Part I”. Courtesy of Cantina Creative.

Continue reading »

In the last few years you’ve seen his work on futuristic user interfaces in “The Amazing Spider-Man 2”, “Pacific Rim” and “Total Recall”. Last summer you’ve seen his true-to-the-metal work on the low-level interfaces in the first season of “Mr Robot”. And his work is currently on display in the first season of SyFy’s “The Expanse”, ranging from the medical and transportation interfaces of Ceres, to the navigation interfaces of the various spaceships, to the transparent blocks of glass that pervade all inhabited worlds of the show. It gives me great pleasure to welcome Timothy Peel of the Junction Box design studio to the ongoing series of interviews on fantasy user interfaces.

In this interview Timothy talks about the wide variety of feature and episodic productions that he’s been working on since the early 2000s, the increasing presence of screens in those productions in the last decade, the difference between impressing and convincing viewers, the overall evolution in the world of episodic television in general and the more specific changes in the quantity and the quality of screen interfaces in it, the world of narrative interface design that supports the story and the plot, and his views on design in general. In between he delves deeper into the almost-invisible screens of “Jessica Jones” and “Mr Robot” that stay true to the nature of the shows, the extravagantly complex interfaces of “Pacific Rim”, and the vast screen universe of “The Expanse” that spans multiple worlds, spaceships and types of interactions.

Screen graphics on “The Expanse”. Courtesy of Timothy Peel.

Kirill: Please tell us about yourself and your path so far.

Timothy: I come from a whole family of designers. My father is an architect and my mother is a designer, a teacher and a painter. I lived in a designed environment my whole life. It was this very beautiful bubble that, of course, would burst many times.

I was always interested in visual arts, specifically graphic design; I’ve always loved graphics even from a very young age.

I went to an arts high school where I was exposed to painting, life drawing, sculpture, and pottery – very much traditional art forms. And then in the early 90s at the Ontario College of Art (now OCAD University), I was introduced to web design, a sort of new revolution, a new economy, a new way of doing things. It was this whole idea of interactivity. After OCA, I started doing very preliminary web design as the internet bandwidth improved. Illustrator and, Photoshop were pretty new. They were radical new tools that changed the way we thought about design.

At the same time I did some temporary summer jobs working in the movie business. Primarily it was building sets, making props and working with SFX. I did things like rig explosives on Johnny Mnemonic and install squibs into the walls for Robocop the TV series. I started to notice some of the drawings and graphics coming from the art department and they seemed like something that I could do. I went back to university and majored in interactive design with a minor in film. I returned to the film industry where I eventually became a senior graphic designer. I have been working steadily ever since.

I was being asked to do a lot of playback and interface design. Back in the late 90s they didn’t really have someone specifically for that job so it usually fell to the graphic designer. It’s still kind of a new job, even though more and more there are times when a film’s major narrative points are being told through a screen or a phone or some kind of user interface.

Over time, I ended up doing more interface design than graphic design and I started to really prefer it. Graphic design is still a primary part of UI/UX but now there’s interactivity, animation, visual effects (VFX), 3D rendering. It’s become a huge task to evolve along with it.

Screen graphics on “Total Recall”. Courtesy of Timothy Peel.

Kirill: How would you describe the evolution of the tools that you’ve been using since you’ve started doing user interfaces? Are they becoming more powerful and easy to use, just as you have more demand for evermore elaborate interfaces?

Timothy: The tools are evolving very quickly, and not always at the same rate. Illustrator and Photoshop are well integrated with After Effects. Cinema4D has some nice plugins that work directly with After Effects now. I switch back and forth between all these design suites as it becomes more efficient, but all that efficiency leads to more complexity and more ambition.

Kirill: You mentioned scripts relying heavily on using phones, tablets, monitors or even whole tables as screens. Was there any specific point in time for you where this became very prevalent, or perhaps it was just a gradual progression over the years?

Timothy: It made a pretty serious jump around 2003-2004. I worked on the remake of Dawn of the Dead in 2003. You have these survivors locked up in a mall as the whole world goes to hell with zombies surrounding them. They watch the end of the world on this vast array of televisions in a fake Panasonic TV store.

Panasonic was actually considering having stores like Sony does, and they came to do a “concept store” with us. We developed all these different news stations as pre-recorded footage. This wasn’t VFX, it was played back live on-set. This is where most of my early experience happened with motion graphics, UI/UX. It was the first time my screen-based content was a very big part of a scene, much more so than before. This had been done on many movies before Dawn of the Dead, but for me personally, the jump was around then.

A few weeks later, I had to make a couple of screens appear to be real touchscreens even before we had real ones that could work on set. We had an operator affect the screen as the actor touched it. It’s funny because all we do is interactive screens now. That was a different time.

Screen graphics on “Total Recall”. Courtesy of Timothy Peel.

Continue reading »

“The Martian” has been one of the major events in the sci-fi genre in 2015, featuring an amazing variety of user interfaces that cover a spectrum of screen sizes, purposes, and interaction patterns. If you’ve been following the ongoing series of interviews on fantasy user interfaces on this site, the name of David Sheldon-Hicks of Territory Studio is not new to you. In 2014 we spoke about the work the studio did for “Prometheus” and “Guardians of the Galaxy”, and last year David talked about Territory’s work on “Ex Machina”, “Jupiter Ascending” and “Avengers: Age of Ultron”.

Now it’s time for the screens of “The Martian”, and there’s no better person to talk about them than Marti Romances who, over the course of 7 months, has created more than 400 different screens for this film. In this back-and-forth between Marti and David they talk about the immense scale of the production, the endless discussions they’ve had with lead engineers at NASA to create interfaces that stay true to their real-life counterparts, and designing screens for the intended purpose – from the small monitors attached to the spacesuit sleeves to the gigantic 9×3 meter screens in NASA mission control center.

Kirill: Please tell us about yourself and your path so far.

Marti: I started in multimedia design as a motion graphics artist when I was 19. That was back in Barcelona, where I’m originally from. I spent four years working on motion graphics for TV advertising and DVD interfaces. Those DVD menus were my first exposure to user interface design.

After that I got a call from Activision here in UK. They wanted a motion graphics artist who had never worked in video games to give them new and fresh ideas on the game they were developing at the time – DJ Hero 3. Mainly I was creating interfaces again – the menus for the game, transitions between screens, the HUD etc. Without knowing it, I was getting deeper into user interfaces.

After a couple of projects with Activision, Nintendo called. They offered a position of the art director for their new game on the new Wii U platform. It was very interesting because it involved a touch screen and the emerging new technology at that time. “Sing Party” was fun and completely different from what I was doing before. I think that when you apply your skills to new industries and new challenges, you learn a lot.

It was at this point that Territory was looking for an art director, and I was ready for new challenges. It was a very small studio when I arrived, around five people, and it was exactly what I was looking for.

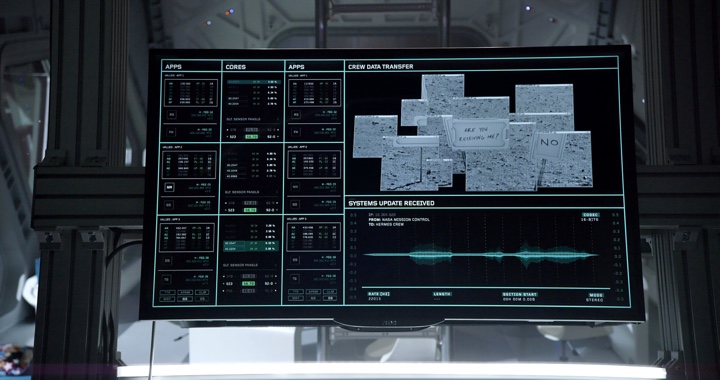

Still of a screen on “Hermes”. Courtesy of 20th Century Fox and Territory Studio.

David: When Marti joined, Prometheus was out and we were working on Zero Dark Thirty. It was really early days in terms of our reputation in film graphics, and we were better known for our work in games.

Marti: And that’s what attracted me to Territory. Having come from TV advertising and video games, I was excited that at Territory both of these worlds were colliding. And on top of that I fell in love with Prometheus. My first projects here were Killzone ‘Mercenary’ and designing UI front-end for the new Xbox One that was in development at Microsoft.

After a couple of months I started on a short sci-fi film “Ellipse”, designing conceptual planetary systems. And then I started on “Guardians of the Galaxy” as my main first film. I went on to work on “Ex Machina”, “Jupiter Ascending”, “Avengers” and “The Martian”, with more in the pipeline.

Kirill: If I can bring you back to the user interface work you did for games, I’d imagine that those had to be very functional for people to interact with all the time. And on the other hand, the interfaces we see in movies are there on the screen, but they are not for me as a viewer to interact with. You might have the actors touching a few areas here and there, but overall they feel a bit less real if I may use that word. How different was it for you to transition into designing UIs for feature films?

Marti: Interface design for video games has to be pragmatic and you have to approach the work with ‘use’ in mind. So, you have to be very precise on core information that’s relevant to the game play at any one time – everything from what visual field do we have to work with, to how big a button can be and how big a number in the HUD is so that without looking you know how many grenades you have left. They do a lot of retina tests on everything. I think that background helped me a lot.

Designing film screens is very different. In “Guardians of the Galaxy”, we worked with fictional technology that no one has seen before, and there’s nothing that you can look at in terms of how you interact with it. The production designer was happy for us to open up the approach and let us imagine that maybe the characters were not touching anything and instead used mindwaves or whatever. It was a fun project and I had to be very open-minded. And it was interesting not to be attached to any technology.

On “The Martian” we worked with real-world technology, and I was thinking all of the time about how the characters would interact with the UI, how a button should look like on a touch-screen when they interact with it while they’re wearing gloves. There was a lot of thought and research behind what we did to make sure that everything looked absolutely credible.

Still of an arm screen on a spacesuit. Courtesy of Giles Keyte.

Continue reading »

As the last few entries in the ongoing series of interviews on screen graphics and fantasy user interfaces have expanded to cover the world of episodic television, I wanted to explore yet another part of the field – animated movies targeting younger audiences. Justin Kohse is the perfect person for the task, as he was responsible for all screen graphics in “Escape from Planet Earth” that was released in 2013. In the last few years he also worked on the TV show “Stargate Universe”, as well as on feature films “Transformers 4” and “The Interview”. In this interview Justin talks about splitting his time between various creative fields, the relentless pace of production work in episodic television, joining an existing visual universe of “Transformers” and working within it, the various aspects of working on an animated feature film where the limitations of physical sets are lifted and what effect that has on the creative freedom to dream up the screens that support the story, and his overall thoughts on the world of fantasy UIs and the transformation that world is undergoing as our everyday lives are inundated with ever-more powerful screens.

Kirill: Please tell us about yourself and your path so far.

Kirill: Please tell us about yourself and your path so far.

Justin: I grew up on Vancouver Island and got into video editing at an early age. Eventually I wanted to figure out how to make title sequences, build graphics, and animate. That’s what sent me to the Vancouver Film School [VFS] back in 2008 to study digital design. After graduating I worked a couple of part-time jobs and freelanced until I found a full-time gig on Stargate Universe as a Motion Design and Playback Artist. After that I continued in the FUI direction and found myself at Rainmaker Entertainment working on Escape from Planet Earth designing and animating for a 3D animated feature. Wanting to change gears I applied for a job with Gloo studios as a VFX generalist where I worked with a team of VFX artists and Motion Designers on something different almost every week (Screen replacement, compositing, explainer videos, 2D and 3D animation, etc..), Later on I moved to West Media Film and Post which allowed me to jump back into the FUI pool to continue working in television and on features and for the past year I’ve been working as a freelance motion designer.

Kirill: It feels to me that there was so much available in the digital world, from powerful and inexpensive cameras, to ubiquitous desktop and laptop hardware, to very versatile suites of software tools. Was that a good time to be getting into the field?

Justin: There seemed to always be an old computer hanging around the house. I could always find a way to get my hands on video editing software, my mother is an artist and a graphic designer as well and with that it gave me access to the earlier versions of the Creative Suite which I would say is what largely led me to where I am today. I wasn’t sure if it was a good time to be getting into the field but it felt like something that could push me further with skills I already had.

Screen graphics for “Stargate Universe“. Courtesy of Justin Kohse.

Kirill: I never went to a film school, so I might be stabbing in the dark here. Was it more on the theoretical side of things, or on a more practical side?

Justin: The digital design program at VFS I would say was more on the practical side. It was largely an overview of web/print design and multi-media. They taught you a scripting, how to shoot on green screen, advanced photoshop, illustrator, after effects, with a bit of art theory and history sprinkled in. Three-quarters of the way through you pick a direction and I moved towards motion graphics.

Kirill: When I went into university to study computer sciences back in mid 1990s, there was all of a sudden a lot of money getting into the software industry as the World Wide Web was becoming a thing. I remember there were quite a few people in my classes being there because of that promise of money and not because they wanted to be programmers. And a lot of those people fell away after a while. Did something like that happen in your class as people got to see what it actually takes to do digital design as a profession?

Justin: At VFS we were thirty when we started, and when graduation day came around it was down to twenty one or twenty two? So a lot of people kind of realized early that maybe it wasn’t for them. It was also a one year intensive and it was an intense experience but i’d say it was definitely an accurate look at the pace of working in the industry. I was 19 and wanting to expand on my skills more where there were many students advancing themselves that had already been working for years as professionals.

Screen graphics for “Stargate Universe“. Courtesy of Justin Kohse.

Continue reading »

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()