With two stellar seasons under its belt, “House of Cards” is one of the best things that happened to the world of episodic TV productions in the last few years. After speaking to the production designer of the show a few months ago, it’s time to turn the attention to the show’s cinematography. Igor Martinovic has joined the second season, collaborating with different directors and shooting all thirteen episodes. In this interview Igor talks about advances in accessible digital cameras and how it affects his field of work, intertwining technical and artistic aspects of cinematography, switching from the feature world to join an existing TV show and defining the visual approach for the second half of the original story arc, the pace of working on multi-episode production and the changes his craft is undergoing in the transition from film to digital.

Kirill: Please tell us about yourself and your path so far.

Kirill: Please tell us about yourself and your path so far.

Igor: I am originally from Croatia where I graduated from film school. During my college years the war broke out so I ended up shooting lots of documentaries during that time. In 1993 when the war ended I moved to New York and have been living here ever since.

Kirill: Were you interested in shooting movies growing up?

Igor: Not really. I started taking photographs when I was 9-10 yrs old. My brother had a black-and-white lab at our home, and I joined him in taking photos, developing them and making black and white prints. It was a nice little hobby of ours. I had no clue that I would end up working as a cameraman one day.

At the end of the sophomore year at high school we were supposed to decide a direction in which to continue our education. I ended up in a high school class specializing in TV and film production. We watched a lot of movies, and instead of chemistry we studied photochemistry as well as optics and other related things. It was an experimental class but it gave me a direction. I realized that this could be an interesting profession.

Kirill: What did you work on when you moved to US?

Igor: I started on documentaries back in Croatia, and continued working on those after I moved to the States. My desire was always to shoot narrative and fiction. I slowly started to shoot short films and features, and it all went from there.

Kirill: In the last decade or so we’re witnessing a transition from shooting on film to shooting digital. Do you see that it’s opening doors to a wider group of people, providing a wider access to the shooting equipment and removing certain technical hurdles like buying film reels or doing lab processing?

Igor: I agree. There’s definitely democratization of the process happening right now. It is a progressive process because it brings so many new people into the field. It opens up possibilities for young and talented kids to come out and present their own vision, their own way of thinking. It is an infusion of a fresh energy.

It feeds on itself. The industry that is producing camera devices is broadening, and the base is broadening as well. They’re helping each other to develop the new visual language. In the last ten years we’ve seen an amazing change in the way people capture images. It’s been a small revolution.

It’s happening on both sides. It’s technical, but at the same time it’s a creative evolution as well. People are using these cameras in many different ways that were not even possible or technically achievable before. And it also opens up ways of seeing things, of presenting things in new perspectives.

Kirill: On the one hand some of the newcomers don’t go through the “official” academic channel of learning the history and the theory, but on the other hand they are not artificially, if you will, bound by those limitations.

Igor: There’s nothing wrong with learning your craft academically. I think that one would want to learn how things were done in the past – in the 20s, 30s, 70s… And the same applies to the theory of filmmaking – you can only benefit from it. But at the same time, if you’re talented, if you know what you want to do and how you want to do it, you absolutely should not limit yourself by having to go through those stages. If one is curious he or she can learn these things outside of the institutional framework.

There are few ways people can come to the point where they have a successful career. One is to work in the industry in supporting positions – camera assistants, gaffers – slowly developing and going up the ladder to become director of photography. The other is to finish a school and go straight to doing things as director of photography. Everyone has their own way to find themselves, their voice and their visual language that represents who they are, that shows how they see the world.

Continue reading »

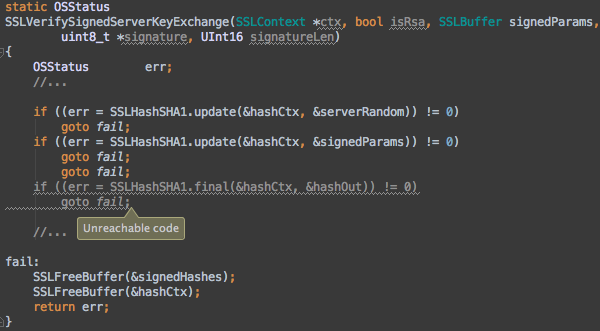

If only they used code guidelines that mandated braces around all blocks. If only they had unit test for this module. If only they had better static analysis tools. If only they had better code review policies.

There’s a lot of hand waving going around in the last couple of days, with everybody smugly asserting (or at least implying to assert) that they would never, in a million years, have made such a stupid mistake. And that’s what it is. Plain and simple. A stupid mistake. With very serious implications that reach into hundreds of millions of devices.

Except that stupid mistakes happen. To everybody. Unless you don’t write code. And if you write code and you really truly believe that you are not capable or making a mistake such as this… Boy, do I have a bridge to sell you.

Which brings me to my (almost) favorite thing in the world. Smugly asserting that I knew better than them and quoting myself:

My own personal take on this is that interacting with computers is too damn hard. Even given that I write software for a living. Computers are just too unforgiving. Too unforgiving when they are given “improperly” formatted input. And way too unforgiving when they are given properly formatted input which leads to an unintentionally destructive output. The way I’d like to see that change is to have it be more “human” on both sides. Understand both the imperfections of the way human beings form their thoughts and intent, and the potential consequences of that intent.

Do I have a solution for this issue? Are you f#$%^ng kidding me? Of course I don’t. But it kills me to realize that after all these decades we are still living in a stone age of human-computer interaction. An age when we have to be incredibly precise in how we’re supposed to tell the computers what to do, and yet to have such incredibly primitive tools that do not protect us from our own human frailty.

Continuing the series of interviews with designers and artists that bring user interfaces and graphics to the big screens, it’s my pleasure to host John Koltai. You have seen John’s work on “Iron Man 2”, “Iron Man 3” and “The Avengers”, and there’s more coming up to the theaters this year. In this interview he talks about graphic and motion design work for commercials and broadcast reels, the ever-evolving world of screen graphics in sci-fi motion pictures, designing in 3D space for stereo productions, the importance of storytelling, his involvement with the just-released “Robocop”, the tension between immersive holographic interfaces seen on the big screen and the everyday real-world tasks facilitated by computers, and finding time for smaller side projects.

Kirill: Tell us about yourself and how you started in the field.

Kirill: Tell us about yourself and how you started in the field.

John: Well originally I went to school to study computer science, and decided after about two semesters that it wasn’t for me. I was a guitar player, so I started exploring some options within the music department in school, but didn’t really find what I was looking for there. I was also taking some film classes, and through that I became really interested in shooting and storytelling. Towards the end of school I took a motion graphics class that a friend of mine suggested.

I didn’t know anything about that world, and it was taught by a guy who did news graphics in Buffalo (where I’m from originally). His name is Kurt Murphy and he was probably the most important person I could’ve met at that point. He really opened my eyes to the world of motion graphics. He was so passionate about the world of design and motion graphics, and as soon as I took that class I knew exactly where I wanted to focus my career.

After that I moved to New York and went to Parsons [school for design], focusing completely on the world of motion graphics, trying to get into broadcast design. Once I graduated, I did a lot of broadcast work, work for advertising and show packages, and it wasn’t until a few years working in the industry that I started doing UI design for films. That happened at a studio called Perception with Iron Man 2.

Left – pitch spot for Dairy Queen, right – broadcast reel for TWC. Courtesy of John Koltai.

Kirill: Before we get to the film side of your career, let’s talk about your work on commercials. How big your team usually is, who you work with and what’s the timeframe?

John: A lot of it varies by the studio. At some of the smaller shops that I’ve worked with – depending on their level of trust with you – you might be the only one coming up with the entire concept and literally doing all the animation and compositing work, working maybe with the creative director at the studio and the agencies that are hiring you. And then you have bigger places with much bigger budgets. At a studio like that you have access to giant CG teams and huge budgets, where you are just a piece of the puzzle, creating more elaborate sequences. It all depends on the project, I would say.

Kirill: So this would be a blend of computer-generated graphics and real-world photography. Do you come in mostly during the post-production phase, pulling these different pieces and combining them together?

John: Again it varies on the job. In some cases I would be a part of the conceptual phase with art directors on both the studio and the agency sides, trying to come up with the concept of the commercial or the promo. And other times they will have a very clear-cut vision – say, sparkles flying out of a piece of a gum [laughs] – and at that point you’re just a piece of the puzzle, and you do what you’re told. Obviously it’s a lot less creative and fulfilling, as you don’t get to build concepts and ideas.

Left – commercial for Icebreakers, right – broadcast promo for Sons Of Anarchy. Courtesy of John Koltai.

Kirill: Is there any consistency in the software tools used to create motion graphics across different studios and freelancers?

John: I would say so, mostly the Adobe stack. You have After Effects for animation and sometimes design, primarily Photoshop and Illustrator for design, and Cinema 4D for 3D elements.

Kirill: How did these tools evolve over the last few years? The requirements from people you work with – directors, production designers, art directors – are getting more complicated each year, I’d assume. Is the software keeping track?

John: I would say that things are progressing from the production standpoint just because computers are getting faster, software is getting more sophisticated, and you can do a lot more. If I look at my work, or just work in general, from five or 10 years ago, as a whole I think that things have progressed tremendously.

Kirill: Going back to your first feature film work on Iron Man 2, how did that happen for you?

John: I’ve always wanted to be a part of a bigger storytelling project. I never really set out and said that I want to make movies, but I always wanted to do stuff that had a bigger audience, that meant a little more. I happened to be at the right place at the right time working at Perception. We had done a lot of title sequences for Marvels animated feature films. Through that we had built a pretty strong relationship with people at Marvel. What ended up happening was that they came to us to help them with one single element – this giant graphic looping behind Robert Downey Jr. during the Stark Expo sequences. We turned that around rather quickly, and on one of the calls they had mentioned that they wanted a timeline sequence for the film.

They invited us to do a pitch on that, and we ended up doing a lot of designs. I believe that the timeline sequence ended up being scrapped or dialed down. But while we were on the second call with them, they mentioned that they liked one of the designs I mocked up for the look of Tony’s cellphone. It was almost mentioned in passing, and we kind of stopped them on the call, and they started elaborating on it, and that’s when we were asked to pitch on that. We developed a bunch of style frames and a motion test for that, and they were very receptive to one of the designs that I did for the cell phone, and that ended up turning into the coffee table as well as the graphics package for the Monaco race, a vintage-style expo logo, and a bunch of monitors throughout the entire film. It was this one element that turned into over 100 shots that we worked on. For that to be my first foray into the movie graphic business, it was really exciting for everyone at the studio and myself.

Touch screen glass coffee table for Iron Man 2. Courtesy of John Koltai.

Continue reading »

Continuing the ongoing series of interviews with creative artists working on various aspects of movie and TV productions, today I’m pleased to welcome Fainche MacCarthy. In this interview Fainche talks about the art and craft of set decoration, approaching the script, researching the specific era and recreating its look, the shooting schedule, working with VFX department on digital set extensions, the evolving collaboration between physical and digital aspects of modern movie productions, and her work on the recently released movie “Snow White and the Huntsman“.

Kirill: Please tell us about yourself and your journey so far.

Kirill: Please tell us about yourself and your journey so far.

Fainche: I was introduced to an art director at Warner Bros through a mutual friend while I was in school. Within one meeting with her, I knew that I wanted to work in movies. There was something about her, and the way movies were made, and how exciting they were. She was incredibly forthcoming with names and numbers of people and I persisted until someone hired me. My first job was as an art coordinator but I also did many of the plans, elevations and site plans as well as running out for paint, etc. I worked my way up, met a few people, started working on TV shows, and then went out on my own and started decorating. When you’re decorating, you have the final layer on the set. Once all the walls and floors are put down, you walk into this empty space which is so exciting. You start to bring life to the space. I was very drawn to that.

I started at the bottom, doing informercials, music videos, commercials and then films. The first proper film was “Alpha Dog”, and then I jumped from big-budget films, to small budget, to medium budgets. So for me it was a mix all size productions.

Kirill: When do you usually join the production?

Fainche: I’ve had good fortune to work with the same people for the past 15 years, and I’ve developed prior relationships with them. They usually bring me in quite early. The production designer will start with the director, maybe a couple of months before I will. They’ll start putting together the looks for the movie, and I’ll join and start budgeting and putting together my research. The research that I do is very detailed and extensive, and as I’m collecting all the information about the time period – “Snow White”, for example, was 12th century – I begin to put together a very real world for the film.

Kirill: How does the usual film script go? Does it delve deep into the details of each set, or is it on a much higher level?

Fainche: Scripts are usually around 100-110 pages, or maybe 120 for a longer movie. The writer can’t really go into heavy description, because that would take up too much space. They would give an impression – like walking into the king’s bedroom – and then you come up with your own research, facts and what actually existed in that time period. The look and the specific design of each room would come from the decorator. However, if there’s something pertinent to the film – he picks up his cup from the side table and takes a drink – you know that you need to supply that cup.

On the set of King Magnus / Ravenna wedding with green screen – built on stage at Pinewood. Courtesy of Fainche MacCarthy.

Kirill: And you want to stay true to the specific era, no matter how far back it goes.

Fainche: Definitely. We did “Super 8” which was set in June 1979. There wasn’t a single thing on the set going beyond that time. Everything we made was before June 1979 – magazines, artwork, paperwork, furniture, rugs, fabrics. It’s not necessarily that camera picks up on everything, but when the crew and the director walk into the set, you don’t want anyone to find any mistakes in your work. The research that we did for “Super 8” was so extensive, as everything was so different from what we have now – consumer products, the way that we looked, the information that we had.

Any time you can do research and really bring the director and the crew as they walk into the set back into that time period, it’s really exciting. And it’s exciting for the actors as well, as they walk in and can get into the character, with every detail around them. You give everyone an opportunity to tell the story and it feels real, it’s grounded in something physical.

On the set of King Magnus bedroom – built on stage at Pinewood. Courtesy of Fainche MacCarthy.

Continue reading »

![]() Kirill: Please tell us about yourself and your path so far.

Kirill: Please tell us about yourself and your path so far.![]()

![]()