Continuing the ongoing series of interviews on fantasy user interfaces, it gives me great pleasure to welcome Karen Sori. As the graphic designer on the recently released “The Circle”, her work brought together the physical and the digital worlds of the story. In this interview we talk what graphic design for film is, how it can be both pervasive and invisible, working on productions of different scopes and being constantly challenged to find solutions to new problems.

As we transition to talk about “The Circle”, we start with designing the physical spaces of that world, and creating a design system that defines the company’s identity. Diving deeper into the digital part of it, and screen graphics in particular, Karen talks about choosing the red color for the logo and the main interfaces to convey the sinister undercurrents of that company’s technology both internally and externally, the visual aesthetics of the interfaces and the decisions made to reduce the traditionally negative connotations associated with the red color, and taking interface elements out of the rectangular confines of the screen and into the physical space around the main character.

Kirill: Please tell us about yourself and your path so far.

Karen: My name is Karen Sori, and I’m a graphic designer for film and TV.

I grew up with the love of movies very much present in my household. My father enjoyed them immensely and always made it a point to share everything he had watched growing up. So many of his memories of watching movies are tied to when he and my mother were traveling in South America as immigrants. It is a remarkable thing that movies can inspire joy and transcend any age, gender, culture, and circumstance of their audience.

After moving to the States from Sao Paulo in grade school, I remember one of my first outings with my newly acquainted cousins was a trip to Disneyland. I didn’t yet understand or speak English at the time so observing the visual feast before me was incredibly surreal. I was old enough to know that it wasn’t real but observing the buildings, the playfulness of scale, the whimsy of the characters– the delight of fantasy really stuck with me.

All through school, I was fortunate that my parents put great value in pursuing a career and life in something one loved. Never was there a moment when they made me feel I had to compromise the pursuit and expression of creativity for something traditional for the sake of convention. So I set my sights on becoming an Imagineer for Disney and the vehicle in which to get there would be an education in architecture.

Through my time in school, I made it a point to experience working at various architecture firms to help inform and better shape an understanding of what professionally practicing meant. And as much as I loved my education and found so much appreciation for a whole new aspect of the world around me, by my thesis year I knew I wanted to shift gears upon graduation and find a career that captured the spirit of world-building like Imagineering and the technicality of spatial design.

I’ve always been a planner so breaking from my own set road seemed terrifying. Ironically enough my father was the one to encourage me to not be bound by expectations (even my own) and to pursue something meaningful and lasting. So I took a chance and made a deal with my parents. For one year I would try and get my foot in the door in the film industry. And if it didn’t pan out into anything real, I would happily return to architecture knowing I had at least tried.

But where to begin? I didn’t know anyone or anything about the industry. I needed to research and get educated on what this world was really like. What is it that art departments do exactly? So I sat down and made a list of every movie I ever enjoyed and thought was visually compelling. I signed up for a month free trial of IMDb Pro (college graduates, especially middle of a recession, aren’t rolling in money unfortunately) and started digging. I looked for production designers, art directors, set designers – anybody that I could contact and would be willing to have an open dialogue with. I had an Excel sheet with all the names, when I’d emailed them, when they called back, so on and so forth. I did my best to not be a huge bother, but persistent enough to express my commitment and curiosity. It was surprising that a number of people actually responded with such sincerity and earnestness.

It was around eight months in when Beth Mickle who designed “Drive” was prepping to do Ryan Gosling’s first directorial movie “Lost River” that my first opportunity to be on a real art department came. I jumped at the chance. I packed my bags and bought a one-way ticket to Detroit.

Looking back, it was the perfect project to get me acquainted with film-making. It felt like summer camp. It was a small crew with a really small budget but wonderfully kind people that wanted to make Ryan’s vision happen. I started out as an art PA (production assistant) like anyone else and worked my way from project to project. Through the ups and downs of the business, I learned and absorbed as much as possible from every job and every person I met.

If there’s one thing I realized in all of this is that opportunities come from anywhere, and from people you may have met for the briefest of moments. There is no reason or rhyme as to when and how things unfold in this industry. So be kind, commit hard work and dedication to your craft, and be grateful you get to do what you love everyday. I am only here because of all those who came before me, opened doors and gave me a chance.

Kirill: When you said that your first experience with doing movies was magical, what about the daily pressure and grind on the set?

Karen: The crazy long hours and the all-nighters didn’t really bother me to be honest because I came from architecture where the hours and expectations were even more insane. I guess my view on “normal working hours” was already distorted to begin with.

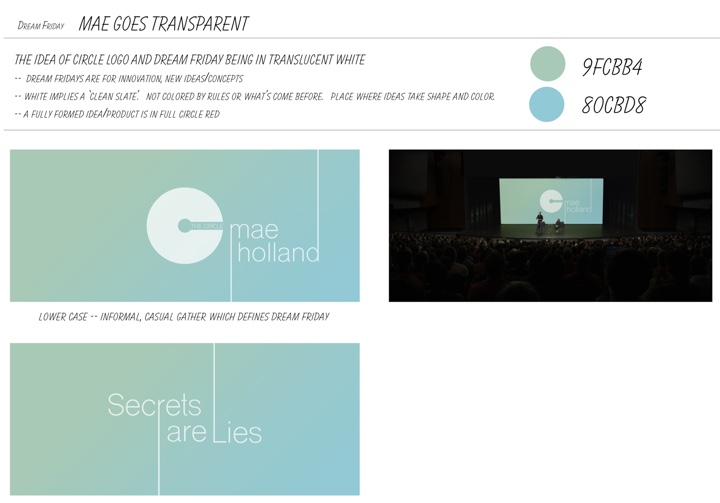

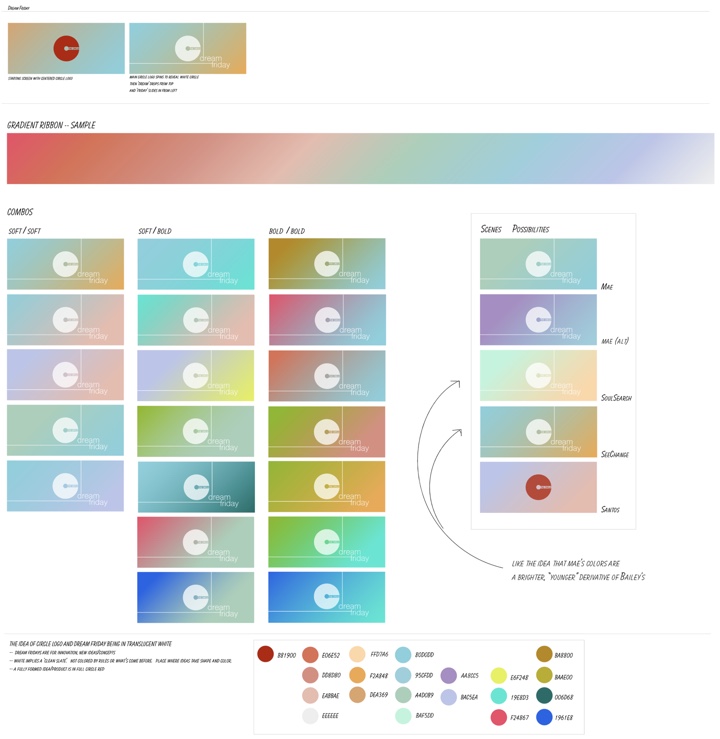

Graphic design for going “transparent” segment. Courtesy of Karen Sori and STX Entertainment.

Kirill: What is graphic design for film? What do you say when people ask what you do for living?

Karen: I get asked that all the time. First thing people think of is that I design movie posters.

I usually preface everything by saying that any time you watch a movie, never does a crew just roll into a space, be it a mansion, a park or a museum, and shoot what is there as is. Everything that you see is considered, curated, designed, created, and carefully placed with reason and intent. Graphic design is in support of that very process.

I can design something as small as a book cover or as large as a 300-foot long mural on a municipal wall along the train tracks in Chicago. It’s making something real out of nothing. That’s the best way I explain it to people. I don’t know if it necessarily sticks [laughs], but that’s how I see it.

Kirill: If we’re talking about productions that take place in the modern time, we all are used to seeing so many different spaces in our everyday lives. Do you think people underestimate how much thinking goes into creating those spaces for film?

Karen: Absolutely. Let’s say you’re watching a drama, and you’re in a cafe. People don’t ever think about the fact that all the menus, the signs on the menus, the logo on the barista’s shirt, are all things that are created specifically for that show.

There’s also this entirely unseen side to all of this – legal clearances. Anything I make has to go through a legal department to clear names, phrases, designs etc. It’s a whole process that is not ever evident when you’re watching a movie. People are always shocked when I tell them that that rather small, almost insignificant logo in the background took a great deal of time to create and be approved for legal use.

Design process for the graphics of Dream Fridays. Courtesy of Karen Sori and STX Entertainment.

Continue reading »

Continuing the ongoing series of interviews on fantasy user interfaces, it gives me great pleasure to welcome Carly Cerquone. In this interview we talk about how much (or little) time screen graphics get in feature films, designing elements to be seen by camera, fantasy user interfaces as a storytelling device, and how she approaches the task of creating interfaces that target specific characters. As we discuss all this and more, we dive deeper into Carly’s work on the recently released “The Fate of the Furious” and “Spider-Man: Homecoming”.

Kirill: Please tell us about yourself and your path so far.

Carly: Growing up, I don’t think I could have ever considered myself “bored”. I spent most of my free time playing sports, watching movies, drawing, painting, and participating in a variety of extracurricular activities. While I enjoyed the fine-arts very much, I was also attracted to science, math, and technology. In middle and high school I enrolled in as many art and AP classes as my schedule would allow, and by my junior year I made the decision to pursue a career as an artist in the film industry.

After a lengthy search and application process, I was accepted into the Motion Picture Science program at the Rochester Institute of Technology. In addition to my coursework, I held jobs as a motion graphics designer, and a live graphics operator for Sportszone Live, our broadcast channel.

The summer of my sophomore year I was offered an internship at Cantina Creative. That year, I spent the two months in Los Angeles and earned my first feature film credit on Need for Speed. I returned the following summer for a second internship, and accepted a full-time position with Cantina immediately after graduation.

I’d be remiss if I didn’t credit my parents. I’m not sure where I’d be if it weren’t for their unwavering guidance and support. They’ve encouraged me in every aspect of my life and I consider myself extremely lucky to have them in my corner.

Screen graphics for “The Fate of the Furious”. Courtesy of Carly Cerquone.

Kirill: You’ve graduated the Motion Picture Science program at RIT. What is special about that program, and what are the challenges that the education system needs to meet in the world that is undergoing such dramatic changes in consumer technology?

Carly: Motion Picture Science (MPS) is a truly unique program. It provides a science and engineering based education in the fundamental imaging technologies used for the motion picture industry. It straddles two colleges – the College of Imaging Arts and Sciences, and the College of Science, and joins a core curriculum in practical filmmaking and imaging science. When I enrolled, MPS had just entered its 5th year of existence, and is still the only program of its kind in the country.

I don’t think it’s realistic to expect the education system to keep up with technology by way of lesson plans or curriculum updates. It’s definitely important for students to be knowledgeable of current industry standards and practices, but that alone won’t be enough to carry them through their careers. I’ve met artists that have graduated from rigorous design programs, others that are completely self-taught, and others still that are educated in an entirely different field! The one thing that each of these individuals have had in common is a drive to learn and continue learning at every opportunity. If an institution can provide their students with the tools and motivation to learn outside of the classroom, they will have created an education to last a lifetime. Students who are fortunate enough to graduate with their appetite for knowledge intact, and the ability to gain it on their own will be able to adapt no matter how frequently the technology changes.

Kirill: There are so many screens in our lives, and so much software that we interact with every day. When you talk with people about what you do for a living, do you think they are surprised to hear that everything has to be explicitly designed?

Carly: Absolutely! Most people know that holograms and other obviously-futuristic elements are created in a studio. They’re often surprised to find out that even the most basic phone screen and computer monitors have been designed, animated, and replaced by an artist.

Kirill: What are your thoughts on the amount of time screen graphics get in feature films? How does it feel to see your work appear and then be gone in almost the blink of an eye?

Carly: Hahaha, well when it’s worded like that it doesn’t feel great! But in all honesty, I don’t mind. Screen graphics exist to support the story. Sometimes their only function is to add to the tone of the film. Other times, they are needed to deliver important information to the audience. As long as my work is visible long enough to perform its intended function, I am happy. I can indulge in the intricacies of the design and animation in the showreels.

Screen graphics for “The Fate of the Furious”. Courtesy of Carly Cerquone.

Continue reading »

Continuing the ongoing series of interviews on fantasy user interfaces, it gives me great pleasure to welcome Khairul “Keko” Ahmed whose work spanned, so far, the worlds of video games, feature film and automotive interfaces. In this interview we talk about what goes into creating video game cinematic sequences, how it compares to working on hero and background screens in the feature world, designing with purpose and supporting the main story, creating design systems that span dozens of screens, and the challenges of car dashboard interfaces, from longer development times to making them informative and immersive. Khairul’s work in feature film was part of “Captain America: Civil War” and “Avengers: Age of Ultron”, and as we got through the topics, we dive deeper into his work on “Batman v Superman: Dawn of Justice”.

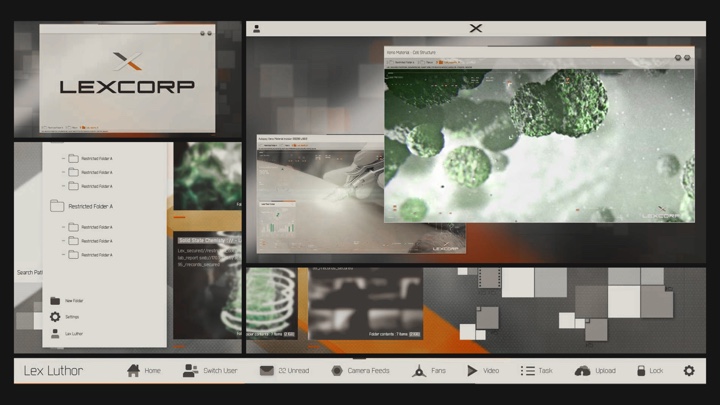

LexOS screen graphics on “Batman v Superman: Dawn of Justice”. Courtesy of Khairul Ahmed.

Kirill: Please tell us about yourself and your path so far.

Khairul (Keko): I am a designer, art director and photographer, gravitationally driven by the need to explore the unknown. I guess that’s what drove me to where I am today!

Believe it or not I was actually on the path of the sciences which I failed completely. Till this day I reflect on that as the best thing that could have happened to me, as this ignited my passion for the things I love doing now.

Within this moment I discovered “Data Flow”, a graphic design book on visualizing informational data, and fascinated by its contents I was lead onto studying traditional Graphic Design at the University of the Arts London. It’s known for its exceptional Graphic Design degree course, and I felt I was at the heart of pursuing my dreams.

On the path of discovering my passion, it was actually the periodic table sequence from the film Iron Man 2 which hit the mark completely. In a full state of visual brainfreeze I was ultimately taken away by the whole FUI experience. This was the first time I fully felt immersed by the use of visual graphics on that level. I think for me this became the pinnacle of understanding FUI, as my obsession for the graphics itself and the need to know the process led me down the rabbit hole.

On the path of discovering my passion, it was actually the periodic table sequence from the film Iron Man 2 which hit the mark completely. In a full state of visual brainfreeze I was ultimately taken away by the whole FUI experience. This was the first time I fully felt immersed by the use of visual graphics on that level. I think for me this became the pinnacle of understanding FUI, as my obsession for the graphics itself and the need to know the process led me down the rabbit hole.

I kid you not – I spent uncountable hours revising the footage, tracing elements trying to imitate the designs and even looking up the artists involved to find some way to reach out to them. Pretty psycho right? Though I’d like to think I was simply super passionate! Funny enough, this hunger led me onto emailing Prologue, the studio behind it all.

Simon Clowes one of the Creative Directors at Prologue at the time was kind enough to reply to my fanboy email which resulted in a dream come true moment! a phone call that changed everything. Completely speechless I was asked if I’d be interested in joining the team as a design intern.

Within my first week of being at Prologue I broke all the rules of being an intern. I was on a mission by the end of the day, to learn everything I dreamt of knowing when revising those Iron Man 2 sequence and to ask all the questions I could possibly ask! Frankly, I wasn’t discreet about it either.

Straight off the bat I introduced myself to the creatives involved with the Iron Man 2 sequence, literally telling them I loved what they do. This sudden exchange allowed me to connect to the artists beyond the level of just looking at their work. I must say it was a great pleasure and privilege to have been able to connect to such amazing creatives such as Simon Clowes, Alasdair Wilson, Ilya Abulhanov, Taka Sato, Paul Mitchell, Manija Emran and Danny Yount. Having spoken to them directly, not only was I able to get a deeper insight into their thoughts, processes and ideas, I was actually being taught by some of the best in the industry.

Besides learning from the best in the industry of FUI, it was actually a car ride with Simon Clowes which rooted me as a core designer today! He asked me right then and there “what do you love doing and what would you want?” Till this day I am so grateful for that question, as what happened after made me pursue the next stages of my life very differently.

It’s moments like this that I feel are so important in life, as it takes you a step back and makes you think about how far you’ve come and where you see yourself going, as you can remind yourself of your goals.

So Mr Simon Clowes if you’re reading this – Thank you!

Prologue pretty much grounded my career! I adopted and developed my aesthetic into a distinctive style that combines my love of title designs / typography and cinematography. Using all the knowledge I had gained, I graduated from University of the Arts London with an Honours in Graphic and Media Design. Shortly after joined the design team at Spov via the recommendation of Alasdair Wilson.

I was immediately immersed into the world of creating high level, advanced screen graphics for featured games such as the Call of Duty series. Designing at such an advanced level with a sharp eye for intricate detail, I am proud to say I’ve crashed a few Ae files in my time. Within this time frame I was inspired by the works of GMUNK, Yugen Blake, Ash Thorp and Jayse Hansen. Seeing their exceptional level of work displayed in the film realm reminded me of my passion for working within films. This was a turning point at which I decided it was time I focused on working on a feature film.

With my goal in sight, I literally was on a mission and nothing could stop me. Without any hesitation (crazy to say) I booked a flight out to New York in the search of reaching my goals.

Honestly, I can’t thank the guys at Perception enough for taking that interview. I met with the infamous John Lepore and Danny Gonzalez, who both instantaneously inspired me about the work I wanted to do and was dreaming of once again!

To give a little background, Perception was doing everything I wanted in terms of FUI for films, whilst also applying their knowledge into creating real world UI. This was a very unique and new direction for me, as I was yet to experience that realm. Landing an opportunity with Perception was literally a life changing experience as this was my breaking point.

Having the talents of John Lepore, Russ Gautier and Doug Appleton mentoring me really changed my perspective in the UI world. They basically taught me one of the most important factors behind Ui design which was “ask yourself why each elements needs to be in frame”. As you know this is very important as a lot of UI tends to get dismissed as beautiful background blur. Perception really focused on giving elements importances to their roles. Story first!

Honestly I could tell you endless amounts of stories about how John Lepore would come behind my screen and fire a million questions with regards to the roles and my choices of UI elements. Moments like that have shaped me into clarifying my design choices, plus adding hierarchy in accordance to the level of importance to the narrative. Johnny was teaching me the rules of graphic design once again, re-rooting me back to my backbone. I feel we all need that from time to time to understand why we are making things in the first place.

Screen graphics on “Call of Duty”. Courtesy of Khairul Ahmed.

Kirill: Back at Spov when you worked on video games, did you do in-game graphics or the cinematic sequences between stages?

Khairul (Keko): It was a mixture of both, depending on the particular project. For instance, on the Call of Duty series nine times out of ten it would mostly likely be cinematic sequences. They are all carefully scripted with a narrative possibly following a chain of events, needing some level of graphic UI to suggest what lies ahead.

Thus my role would be designing elements for mission briefings, highlighting key objectives, schematics of buildings etc. At times I also took part in the early stages of enhancing the multiplayer experience for the Call of Duty series. This role required me to challenge the realm of current gaming experiences and push the boundaries of elements such as simple HUDs, weapon loadouts, maps and so forth.

It would even go down to creating a style guide that could be implemented into the game itself. This was actually the case for Batman: Arkham Knight. The original piece that is on my site is actually part of a pitch, which then allowed Spov to continue their work on the actual game. What we submitted was in fact a teaser suggesting Bruce Wayne booting up the batcave. Rocksteady Studios fell in love with the visual language and aesthetics so much that they felt each element was tailored to the look and feel of Batman. Thus they went full steam ahead to implementing the same stylistic approach in the game.

Screen graphics on “Batman Arkham Knight”. Courtesy of Khairul Ahmed.

Continue reading »

As usual, DragonCon comes to Atlanta over the Labor Day weekend. These are my personal highlights from the opening parade this year.

![]()

![]()

![]()