Continuing the ongoing series of interviews with creative artists working on various aspects of movie and TV productions, it is my pleasure to welcome Stuart Bentley. In this interview he talks about the evolution of cameras and lights at his disposal, the changing landscape of the art of storytelling, collaborating on set and working on episodic television. The second half of the interview is about Stuart’s work on the recently released “SS-GB”, a five-part BBC drama mini-series set in a 1941 alternative timeline in which Nazi Germany occupies the United Kingdom.

Kirill: Please tell us about yourself and how you started in the industry.

Stuart: I’m Stuart Bentley and I’m a cinematographer. As long as I can remember I was into drawing and painting and generally making pictures. My dad is a really keen photographer so we always had cameras around when I was a kid

When I was around twelve or thirteen I got massively into skateboarding. After a few years, me and my friends started taking photos and filming each other, and it became something that we did every day. That was all happening while at school I was becoming more interested in art and photography. We had a small dark room in our school where I was doing my stills.

Then I went to art college, I did a fine art degree where I did a lot of painting, filming, and all kinds of other disciplines. All through that time I was still very much into skateboarding, and as some of my friends were becoming really good at it, I started to film a bit more seriously. We would travel all over the place, getting paid here and there and making our own skate videos. So I did that when I was younger, day to day, we would be out there all day every day, rain or shine.

At the same time I was studying art and photography. I was shooting, editing and directing short films with my friends, and the more I did that, the more I realized that I liked filmmaking. It wasn’t necessarily just about skateboarding filmmaking, but rather the whole process of it. That’s when I started to veer off the skateboarding path, and got into doing music videos and commercials.

At the same time I was studying art and photography. I was shooting, editing and directing short films with my friends, and the more I did that, the more I realized that I liked filmmaking. It wasn’t necessarily just about skateboarding filmmaking, but rather the whole process of it. That’s when I started to veer off the skateboarding path, and got into doing music videos and commercials.

Eventually I moved to London and went to the National Film School. I was excited about the whole process of lighting and learning about it. I never had an opportunity to work on a film set, and I didn’t really know anybody who worked in film or television. I didn’t really have any understanding of how film sets worked, and it felt like such a hard world to find your feet in. That was in late ’90s, before you could go onto the Internet or Youtube and get some info about it, or get contact information. I remember going to the BBC in Manchester with a VHS showreel, and literally asking at reception “who I do I need to speak with to be a cameraman?!!”[laughs] It felt like a very closed and difficult world to get into.

That is part of the reason why I moved to London and went to the film school. A lot of my skateboarding friends did the same, and they became runners or production assistants or production secretaries or whatever. Right after the film school I started shooting music videos, and online commercials – we all were helping each other. It was such a quick process of shooting one music video after another, and it led onto short films, dramas, and feature films. And that was my way of negotiating it in there [laughs].

Kirill: If you look back over all those years that have passed, how would you describe what happened in the world of technology around cameras?

Stuart: When I started filming back when I was 13, we were shooting on massive VHS cameras, Hi8 or Digital8. My friends dad had a Digital8 camera, and our minds were blown! It was the most amazing thing. Then Sony VX1000 camera came out, and it became the staple of the skateboarding industry for the next 10-15 years. That was it, and that was all anybody knew.

Kirill: Are you talking about the lights themselves, and how the most recent camera models capture the nuance of the light?

Stuart: You can go back ten years or so when the RED camera came out, and that was a real game-changer for me. I was shooting a lot of music videos and online / low budget commercials at the time and, if you could afford it, you could shoot on 16mm or 35mm film, but other than that you were using dodgy adapters to stick a prime lens on something like a video camera. When RED came out, it was a very accessible and cheap way of getting the “35mm look” for a very low budget.

The most exciting thing for me recently is advances in LED lighting. I was recently shooting a film and we had hundreds of sky panels in a studio all rigged up to an iPad. We could do chase sequences, switching between night and day in a push of the button. We could program it all right on that iPad, shooting a car sequence in a studio with LED panels. I find it incredible, and it gives the DP (director of photography) such a huge range of subtle and sophisticated tools to achieve the most fantastic images.

Kirill: As you mentioned that things have plateaued a bit in the camera technology, as an outsider looking in, my impression is that the current advances seem to be focusing on adding even more Ks to the camera resolution – talking about 6K and 8K nowadays. Do you think that there’s a certain limit beyond which your eye doesn’t get anything new that is useful?

Stuart: I’ve never been the kind of person that obsesses over the technicalities of pixel counting. I think that you can see an image that was shot on video with its own texture, quality and beauty. Just become something has a high resolution, to me it doesn’t correlate in any way to the quality or enjoyment of the image.

There are certainly benefits to it though, if you’re doing something heavy in post-production that needs any kind of image manipulation, better resolution can help to qualify what you would call a “good image”.

My approach to looking at cameras, be it 16mm or RED or Alexa, is to see them as tools for the job. Each job is unique. Each job has its own challenges and solutions. You have to pick the best tool for the job, and it’s as simple as that. They all have their own beauty and aesthetic, which you can embrace and manipulate. I don’t think I can say that one of them is better than the others, for me it just doesn’t work like that.

Kirill: As you went through the path of doing music videos and commercials, to working on TV shows and feature films, do you remember anything that was particularly surprising on the bigger productions?

Stuart: I’ve done a lot of short films, and that’s a good way to prepare for what a feature presents to you in terms of the pace and the challenges. It felt like a very natural progression to me. And the same goes for the music videos as well that generally have a very quick pace. When you get to a TV drama, you’re already used to that kind of pace and intensity.

The first TV show that I did was period drama, and that was quite an interesting challenge. I’d not done shot period work before so it was a great opportunity to learn about shooting period drama and trying to deal with all the challenges that entails.

Continue reading »

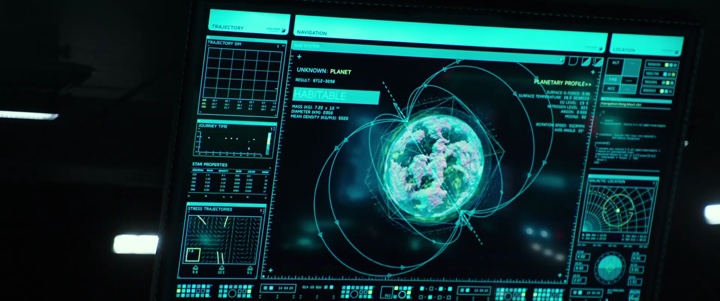

Continuing the ongoing series of interviews on fantasy user interfaces, it’s my delight to welcome Martin Crouch. In this interview we talk about managing dozens of screens on set, creating design systems that scale fluidly across screen configurations, and balancing the realism of our everyday interactions with technology with demands for novelty and screen time scarcity. As we discuss all this and more, Martin goes into the details of his work on “The Matrix” sequels, “I Frankenstein”, “Superman Returns”, “Wolverine”, and the recently released “Alien: Covenant”.

Screens of “Alien: Covenant” by Martin Crouch.

Kirill: Please tell us about yourself and your path so far.

Martin: My name is Martin Crouch and I run a small design studio in Surry Hills, Sydney that specialises in screen graphics for film and television.

Kirill: What drew you into the field of motion graphics, and how has that changed since you’ve started working professionally in this field?

Martin: My training and experience during the ’90s was in print based graphics design, and I had unfortunately spent too long working in advertising, and was looking for a change. Around 1999 I had an opportunity to work on some titles for a local TV show, and had a good experience with that job I decided to reorient my work towards motion graphics.

Martin: My training and experience during the ’90s was in print based graphics design, and I had unfortunately spent too long working in advertising, and was looking for a change. Around 1999 I had an opportunity to work on some titles for a local TV show, and had a good experience with that job I decided to reorient my work towards motion graphics.

I did a Masters Degree at The Australian Film Television and Radio School, concentrating on VFX for film, but even after that was still drawn to motion graphics. Soon after graduating from that course I landed a screen graphics gig on Matrix 2/3 being shot in Sydney at the time, and have concentrated on that kind of the motion graphics ever since. Since then I have designed and animated screen graphics for “Superman Returns”, “The Wolverine”, “I Frankenstein”, “San Andreas”, “Alien: Covenant”, “Pacific Rim: Uprising” and “Aquaman”.

Kirill: Do you have any difficulty introducing yourself to people that you meet at a party as you try to summarize what it is you do for living?

Martin: Early on yes, it was a longer explanation, but more recently there is a greater awareness I think of screen design for film and television, and the inclusion of motion graphics in general – visualising text messages and emails are common place on TV now, so that helped increase the visibility of the work we do. There is a greater range of references to site when explaining it.

Screens of “Alien: Covenant” by Martin Crouch.

Kirill: You split your time between the worlds of feature films and projection. Are these aspects of your work completely separate, or is there some cross-over of ideas and explorations?

Martin: The split was born of necessity, as there weren’t that many large scale screen graphics jobs going locally. For me there was a 5 year gap between Matrix 2/3 and Superman Returns. Some of the people I had worked with on films early on were now working with companies specialising in large scale architectural projection, so I would join them on projects, but usually in a Technical Art Direction position. I mainly dealt with the technical aspect of setting up working templates for C4D and After Effects, and liaising with the companies providing the projectors, and making sure everything lined up from one end of the post production pipeline to the other.

There are obvious overlaps, mainly with the tools we use on both kinds of jobs, but fundamentally it’s a very different kind of work. The projection work can lend itself more to a short film sensibility, you get more time to work with a narrative and engage with an audience. Screen graphics is there to support the story telling, as one part of a much broader range of screen design elements.

Screens of “Alien: Covenant” by Martin Crouch.

Kirill: It feels that with so many screens around us in our daily lives, it’s hard to imagine a film set in the present or near future without screens. How do you tackle the challenge of working on such a production and coming up with new and fresh takes on those interfaces?

Martin: Depending on the film’s setting you draw a lot from the rest of the set decoration for those kind of cues. Anything historical or current will have its own set of rules that govern they way the interfaces work. It’s not always about new and fresh takes, and more about working within a familiar visual language. Of course that’s the starting point, and you try to expand upon it.

Screens of “Alien: Covenant” by Martin Crouch.

Continue reading »

The art and craft of storytelling in feature and episodic productions has been with us for more than a century, and the roots of storytelling in our culture go as far back as humanity has existed. Throughout the interviews I do with creative artists that work on these productions, we talk about the evolution of storytelling from the artistic and technical perspectives, focusing on the today. But what about tomorrow? To help me define and answer that question, it is my delight to welcome Andrew Shulkind.

Andrew is at the forefront of a new generation of storytellers that want to redefine the entire cinematic experience that has been confined, for better or worse, to a hard flat rectangular surface in the movie theater, in our living rooms, and most recently on our mobile devices. Drawing onto his diverse experiences in the realms of augmented and virtual reality, we dive into what the near future holds for both creators and the audiences, tapping into data to understand what works best, the technological challenges on the road ahead, overcoming the inertia of the traditional world, and immersing the viewer in new, exciting and yet-uncharted realms.

Andrew Shulkind comes from a classic background in traditional cinematography and continues to shoot broadcast commercials and films for theatrical exhibition.

Kirill: Please tell us about yourself and your path so far.

Andrew: After film school at NYU, I worked at Panavision, and joined the Cinematographer’s Guild. I moved up the ranks from Camera Assistant and Camera Operator to Remote Head Technician and then Cinematographer. I cut my teeth on a bunch of big studio movies where I moved up quickly as an apprentice under some of the best cinematographers in the business like Janusz Kaminski, Darius Khondji, Emmanuel Lubeszki and Don Burgess.

Looking back I see a much clearer line to the present than it felt at the time. Early on, besides camera assisting, I was helping with color management. Kodak and Panavision had jointly developed a piece of software called the PreVIEW System that allowed cinematographers to virtually emulate nuanced looks to visually communicate to the lab how we wanted the film processed, back when it was all photo-chemical. For 100 years, motion picture film was processed using printer lights, playing with intensity, brightness and density of red, green and blue, and you would influence the look of the daily film processing (called “dailies”) to get the dailies to get you as close as possible what you wanted the final look of the film to be.

This new system allowed us to experiment non-destructively earlier in the process, making the need for a fixed reference for the lab even more important. I became the liaison between the cinematographer and the film laboratory to communicate those choices. As that process moved beyond printer lights to scanning the film for a digital intermediate (DI), it required an even more specific language for delivering the original creative intention through technical means to achieve a digital finish.

All this is to say that we as we’ve moved from photochemical photography to capturing on photosites and finishing digitally to watch a panel of pixels on a screen or mobile device, the business of capture is changing because suddenly we’re photographic more dynamic range than we can display. This reality requires us to decide what information we want to keep, what we’ll throw away, and it becomes as imperative to be able to communicate this abstraction to others how we want this thing to look when it gets delivered.

I’ve always been interested in the intersection of art and technology and each role I’ve had is a different blend of those two fields. In the commercial and music video world, I liked to find efficient ways of working in new emerging technologies and ended up being asked to shoot product tests for new camera, storage, and lighting manufacturers. I do a lot of visual effects heavy stuff and we are always using compositing, and motion control and motion capture, so I spend a lot of time activating emerging technology in the pursuit of dynamic storytelling.

We shot a bunch of early interactive content, including the first piece of content designed for an iPad; we built a tiny stereo 3D camera for shooting live action handheld, I often get to play with LED and plasma lighting and other technologies before they come out because on set we’re always thinking about what we can do to save time and money and tell the story efficiently and differently. And the tools that we have to do that is increasing exponentially by the day.

Then, around four years ago I was doing a commercial that required us to shoot 360° background plates. We needed a professional level of resolution, color gamut, reliability and monitoring. It didn’t exist so I brought together some partners to finance and build it. In so doing, we ended up building a high-res 32K 18-camera 14-bit uncompressed camera that remains the highest quality capture device for shooting 360˚.

We used it on a ton of other projects in this space, but other commercial and film producers and directors and studios that I had worked with in the past started reaching out for 360˚ expertise and so I ended up doing a lot of early 360° VR projects for various companies like Samsung, Google, Nokia, Facebook and others with my camera and others. Then it moved to those folks reaching out to have me consult on how to build or optimize their 360˚ cameras.

Andrew Shulkind inside of a hot air balloon for an automotive project for Chevrolet.

From there it moved into helping agencies, brands, networks, and studios, strategize how they can best use VR/AR content more efficiently and more strategically. All the while, I was still shooting traditional commercials and movies. So immersive consultation morphed into consulting and speaking about overall content plays to shape the future of entertainment content, bridging how traditional media, advertising, sports, esports, live streaming, immersive, and interactive content, and gaming rely on each other as part of a bigger strategic initative.

About two years ago, I was producing a movie property and that macro level of awareness got me thinking about how inefficiently properties are valued with all the data we have at our disposal. So a group of data scientists and I started developing a toolkit to scrape web data and user behavior to understand audience sentiment. You analyze that and start making assumptions on how a product or a property will perform in a market – whether it’s a product, a personality, a film, or a commercial.

I think a lot about algorithms and how well it works for Spotify, how challenging it is for Netflix, and how studios think this kind of technology undermines their secret sauce. In some ways, when Netflix adds a movie to their library, it seems to make it harder for users to find what they want instead of easier. You have new tools and techniques that allow us to tell stories in different ways, but if improperly curated, it becomes a mess. As a storyteller who has spent a career integrating technology in authentic ways, I feel a responsibility to get involved. So that’s what has driven what I’ve been up to this minute.

Continue reading »

Continuing the ongoing series of interviews with creative artists working on various aspects of movie and TV productions, it is my pleasure to welcome Eric Koretz. In this interview he talks about the evolution of digital hardware and software tools at his disposal, the changing landscape of the art of storytelling, working on commercials, minimizing disruptions on set, and how film compares to other art forms. The second half of the interview is about Eric’s work on the recently released “Frank and Lola”, a noir romance of desire, infidelity and jealousy starring Michael Shannon and Imogen Poots.

Kirill: Please tell us about yourself and your path so far.

Eric: My name is Eric Koretz and I’m a cinematographer.

I graduated from the communications design program at Syracuse University. I had a design company in school doing graphic design and motion graphics. I moved to Los Angeles after graduating and continued doing the design work. After a year of doing that I realized that I hated it, and that I wanted to do film. So I shut everything down and started PA’ing on music videos and commercials. That was back around 2001.

I also did a lot of still photography, but at that time I didn’t know that I wanted to be a cinematographer. I didn’t even know what it really was. I was more interested in directing and writing, and that’s how I started. I applied to the American Film Institute for cinematography, because I naively thought that I would just learn the camera work, while keeping to do directing and writing. My portfolio was pretty strange – photography and those hybrid projects.

When I got in, everybody else had so many years of experience and it was a steep learning curve for me. But as it went along, I realized that cinematography was all I wanted to do. AFI was a great experience. I learned a lot there from the classes but also from the guest DP’s that would come in to teach, and also from the other students.

On the sets of “Frank and Lola”. Courtesy of Eric Koretz.

Kirill: Would you say that the industry’s transition to digital opened up the field and democratized it in a sense? It takes not that much money to get a reasonably good equipment these days.

Eric: When I was in college, those 3-chip CCD digital cameras started coming out, and they changed everything. I started using those for my hybrid projects, and they were great. But I still learned film, and I was shooting video and editing on A/B rollers. AfterEffects and Final Cut were just coming out, but that’s what you had before for editing. You would take two video-tape decks, and cut between them by rolling back and forth. That’s what I learned in college before those software packages came out.

I shot film in under-grad, and I also shot film in grad school. That’s when the first big digital cameras started appearing, with the first “Star Wars” prequel using Sony 900. And after graduating AFI that’s when 5D came out. I bought it mostly for stills, and then fell in love with the video aspect of it. And it changed everything, because you could just go out and have this beautiful quality without paying that much money for the more expensive gear. That opened up a whole new world.

I did a lot of 5D cinematography right when it first started off. I was sort of on the forefront of shooting with 5D, and I think it really helped. The normal process when you get out of school is to crew and work your way up, but I was shooting all the time. I did a lot of documentaries and smaller commercial projects, and started to build from there.

Kirill: Do you miss those days, or the physicality of film as medium?

Eric: I was always trying the next new thing in terms of digital. I love the immediacy of digital. I love to be able to manipulate the image and see what you’re doing live on set. I have absolutely no nostalgia for film, and that’s different from a lot of other DPs [directors of photography]. I love what you get with the new digital cameras. I don’t miss film at all.

On the sets of “Frank and Lola”. Courtesy of Eric Koretz.

Kirill: If you look at how the technology is changing in your field, do you think there’s a lot of revolutionary steps ahead of us, or is it more about incremental evolution? Is it close to reach the maximum potential of technology at this particular phase?

Eric: The steps are definitely incrementally smaller. The main camera people are using now is Alexa Mini, which is mostly because of its size and the media that it uses. However it’s an “under-spec’d” camera. The max resolution is 3.4K, but you have to shoot open gate raw to achieve that. People have been using this camera for the last two years, while there are other cameras from RED, Sony and Panasonic that have 4K+ resolution.

It’s really about the color science, and how accurate and natural you get the colors. That’s what I’m mostly interested in seeing improved. Alexa does it beautifully, and all the other companies are improving. That’s why I still use the Alexa. I love the color science.

The push for resolution only matters in terms of how you’re viewing it. Most consumer TVs that are coming out now with decent to best specs are 4K, so it’s only natural for the cameras to progress to be 4K to match that. And the projectors that come out to be used in movie theaters are all 4K. It only makes sense to have the resolution of what your final output is going to be.

Kirill: What about the artistic side of it? Does it mean anything to jump from 4K to 6K, for example?

Eric: Artistically, I don’t think it matters. It’s more about the colors and the color science, to me anyway. I’m not against more resolution. Most DPs don’t like it when you re-frame after the fact, but it gives you the ability to sometimes shoot one size and then crop in or move it around. But it doesn’t really matter to me.

On the sets of “Frank and Lola”. Courtesy of Eric Koretz.

Continue reading »

![]() At the same time I was studying art and photography. I was shooting, editing and directing short films with my friends, and the more I did that, the more I realized that I liked filmmaking. It wasn’t necessarily just about skateboarding filmmaking, but rather the whole process of it. That’s when I started to veer off the skateboarding path, and got into doing music videos and commercials.

At the same time I was studying art and photography. I was shooting, editing and directing short films with my friends, and the more I did that, the more I realized that I liked filmmaking. It wasn’t necessarily just about skateboarding filmmaking, but rather the whole process of it. That’s when I started to veer off the skateboarding path, and got into doing music videos and commercials.![]()

![]()