Continuing the ongoing series of interviews on fantasy user interfaces, it’s a delight to welcome Danny Ho. His path in the industry started almost 30 years ago, at the cusp of the transition from pre-recorded video decks to fully interactive computer generated graphics. Under his leadership, Scarab Digital is a monumental presence in the field of screen graphics (and well beyond), with over a 100 productions under its belt, including more than 1,000 episodes of some of the most memorable television in the last couple of decades, from “The X-Filed” to “Charmed”, from “Sanctuary” to “Siren”, from “Yellowjackets” to “Monarch”, as well as the entire span of the DC television universe in the last 12 years – “Arrow”, “Supergirl”, “Legends of Tomorrow”, “Batwoman”, “The Flash”, and “Superman & Lois”.

In an almost impossible task to fit all of this into one interview, Danny talks about those early days of computer generated graphics and the evolution of hardware and software stacks, challenging his artists to make an impact with their work, how much resolution is too much, the impact of Covid, and the looming emergence of generative AI tools.

Kirill: Please tell us about yourself and the path that took you to where you are today.

Kirill: Please tell us about yourself and the path that took you to where you are today.

Danny: It was back in the 24-frame CRT computer playback days, as practical on-set video playback was already established. There was little post work, and most of it was making real graphics on set, right at the cusp of pre-recorded rendered output from a video deck. You would play linear video, there was no interactivity, and production was used to that. It was done on a three quarter inch or Betacam decks, fully synced to an actual CRT that was synchronized with the film camera.

I got exposed to that through the company that was doing that process on the computer side of it and starting early explorations into interactivity. My buddy was helping someone else do it, and he didn’t mind company. I would go with him to the set and he was, of course, designated to do the work. In between takes I would watch him rush, and try to cable things up, and go to the monitor, and connect to the computer. You’re always under a timeline, and there’s always a struggle of a sort. So of course, I’m not going to sit there and watch him [laughs]. I would go and help him and connect everything until it was all done – and then the actors would work with his stuff.

As I watched and observed, I started thinking that these guys have something here. This is not going to go away. This is going to become more demanding, because we’re natural geeks. We just know how to do this. The old legacy was purely video. They have no idea how to make anything interactive. And sure enough, they landed “The X Files” season two. From there Chris Carter [the creator of the show] became the hottest thing and started doing other shows like “Millennium”, and I ended up working on all those spin-offs for Chris. That was the training grounds for growing this whole thing and taking it to the next level.

Those three quarter inch decks and BetaCam decks were big pieces of equipment, and they had hard cases on them. If you had more than one source, you needed more than one deck, and you have to help carry these things around. I could see the guys who had the market doing video would eventually converge, and you would have a computer that would be able to eventually play video. You could see that coming, even if it wasn’t immediate. It was years away at that point.

I was able to do both. I worked with the video guys and I worked with the computer guys. Back then I did everything as one person – I would coordinate or shoot on set during the day, build graphics at night, then do the whole cycle again the next day. I was burning the candle at both ends. And eventually, as I coordinated projects, you build a network and you solve other people’s problems. So they give you a call and say “Hey, can you help us on our show?” I can say that I was one of the only ones at the time that could do both – I can do the computer and I can do the video playback stuff. The video guys didn’t want to learn the computer side, so they would recommend this fellow who’s well-known in the community. His name is Klaus Melchior and he cornered the market in terms of video.

I knew there would be a certain point where he was going to sail off to the sunset and retire, and sure enough he did. I was happy for him that he was able to retire, he’s an awesome guy. So we picked up the pieces and took the reins for this transition to using computers to play video interactively.

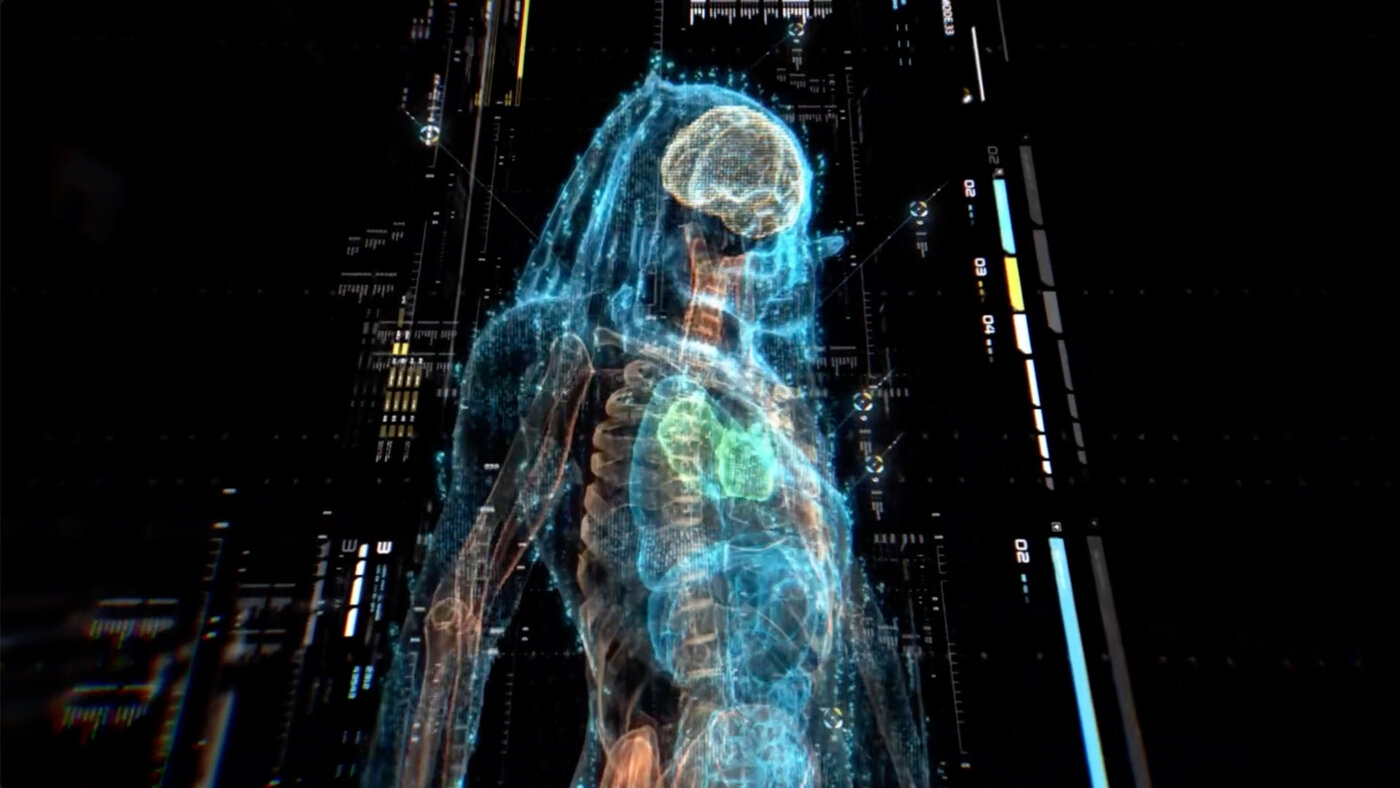

Screen graphics for “The Predator” (2018), courtesy Danny Ho and Scarab Digital.

Kirill: Was there a particular point in time where it felt that computers are powerful enough to take over back then?

Danny: My brother had an internship with Alias Wavefront that later became Maya. I remember visiting him and then he showed me a little trailer, just like we see them every day now, a trailer of a movie. It was playing full real time on an SGI computer, and it was so foreign of a concept to see a video file playing on a computer. It was full resolution and completely smooth. Unbelievable at the time.

It gave me a taste of what the future was going to be on a typical regular computer. It was mind blowing at the time, but of course to us now it’s nothing.

Kirill: How wild is it to look back and remember those days and look at your desk now?

Danny: It’s unbelievable [laughs]. Your phone has more compute power than what the computers were using at the time. If you take the concept that every year you have compute power doubling, it’s pretty staggering.

That’s somewhat of my sweet spot of what I bring to a company. I was able to see where the trends are going, and what the demand might be, and what people might want based on what’s happening now and what’s possible in the future. That is how I’ve grown the business, trying to always stay ahead, looking at what tools might be out there.

There are times I take tools that are completely not meant to do anything related to film or graphics, but they might have to fulfill a purpose for us. We adopt them into the workflow, and we’re always eager to improve and make what seems impossible, possible. Look at the visual effects these days. At one point it couldn’t do plastics and things that look reflective that well. And then later it can do fire and water. It is always progressing. There was a time back then when I was contemplating our company to also do visual effects. Do we do visual effects or do we stay in interactive motion graphics? If you think about what the producer wants, and consider what is doable in VFX. Then you graph VFX against what the producers want vs achievability, they are running almost in parallel, and almost never cross. It’s very difficult to exceed the expectations of a producer for any visual effects. It’s definitely more attainable now, especially when you throw enough money at it.

Screen graphics for “The Flash” Season 8 Episode 19, courtesy Danny Ho and Scarab Digital.

Continue reading »

Continuing the ongoing series of interviews on fantasy user interfaces, it’s my pleasure to welcome Clark Stanton. In this interview he talks about the chaotic nature of productions and how screen graphics fit into supporting the story, differences between working on set and in post production, the pace of episodic productions, and the potential place of generative AI in this creative field. In between these and more, Clark talks about his work on screen graphics for “Chicago MED”, “Free Guy”, “Moonfall”, “Tomorrow War” and “The Peripheral”.

Kirill: Please tell us about yourself and the path that took you to where you are today.

Kirill: Please tell us about yourself and the path that took you to where you are today.

Clark: Hey, I’m Clark Stanton, I’m a creative director and playback graphic supervisor at Twisted Media. I have been creating and facilitating screen graphics for a little less than 11 years. I started after school at a luxury realty company, and moved on to freelance motion design before landing my first full time job at a small production company. I started my career in film and TV after I met Derek Frederickson (who you’ve also interviewed) at a Chicago motion artist meetup where we became friends. A little later on when he got particularly busy, and convinced me to drop my other motion design job and join Twisted Media as his first full time employee. I had no idea what to expect and was incredibly lucky to fall into a dream job.

Kirill: Do you ever think how lucky we are to have been born into this digital world, and not 200 years ago where we would have to plow fields as peasants?

Clark: Absolutely. I’ve been a nerd through and through since I can remember. My brother and I started the first Starcraft club at our junior high. We were always networking computers across the house and playing with technology. We were fortunate enough to have access to some of that pretty early on in our development, and it spawned a love for computers and technology – that helped lead me to where I am in film. Honestly, I can’t even imagine doing anything else.

Kirill: As you joined the field and got a glimpse or two about how the sausage is made, if you will, do you remember being particularly surprised by how things work behind the scenes?

Clark: I always thought that every production had a plan that they were executing, these perfect machines that churned out magic. But the real nature of production is there is plan, but it’s always chaotic. You have all these individuals coming on a new group project, and everyone’s learning how to work with each other well. They’re building the plane in real time, making decisions in real time. Production might be focusing on one area or another because it’s extra complex, and our part in telling the story is usually pretty small in the grand scheme of things. So because we always have the golden parachute of going green and figuring it out later in post. We often get pushed to the edge of that creative decision making.

It’s been interesting to learn how to advocate for yourself, to make sure that the production gives you the answers you need, so that you can solve their problems and move the story along – hopefully in camera. And when that doesn’t work, then it’s always fun jumping into post and learning where the edit went and what actually needs to be there. Sometimes you have a huge elaborate graphic that you built for set, and it gets cut down. Maybe they liked the actors’ reactions, and now they’re changing the edit and trimming down or transforming what was in the original script to make the story more clear, until you’re left with just one of the original ten beats.

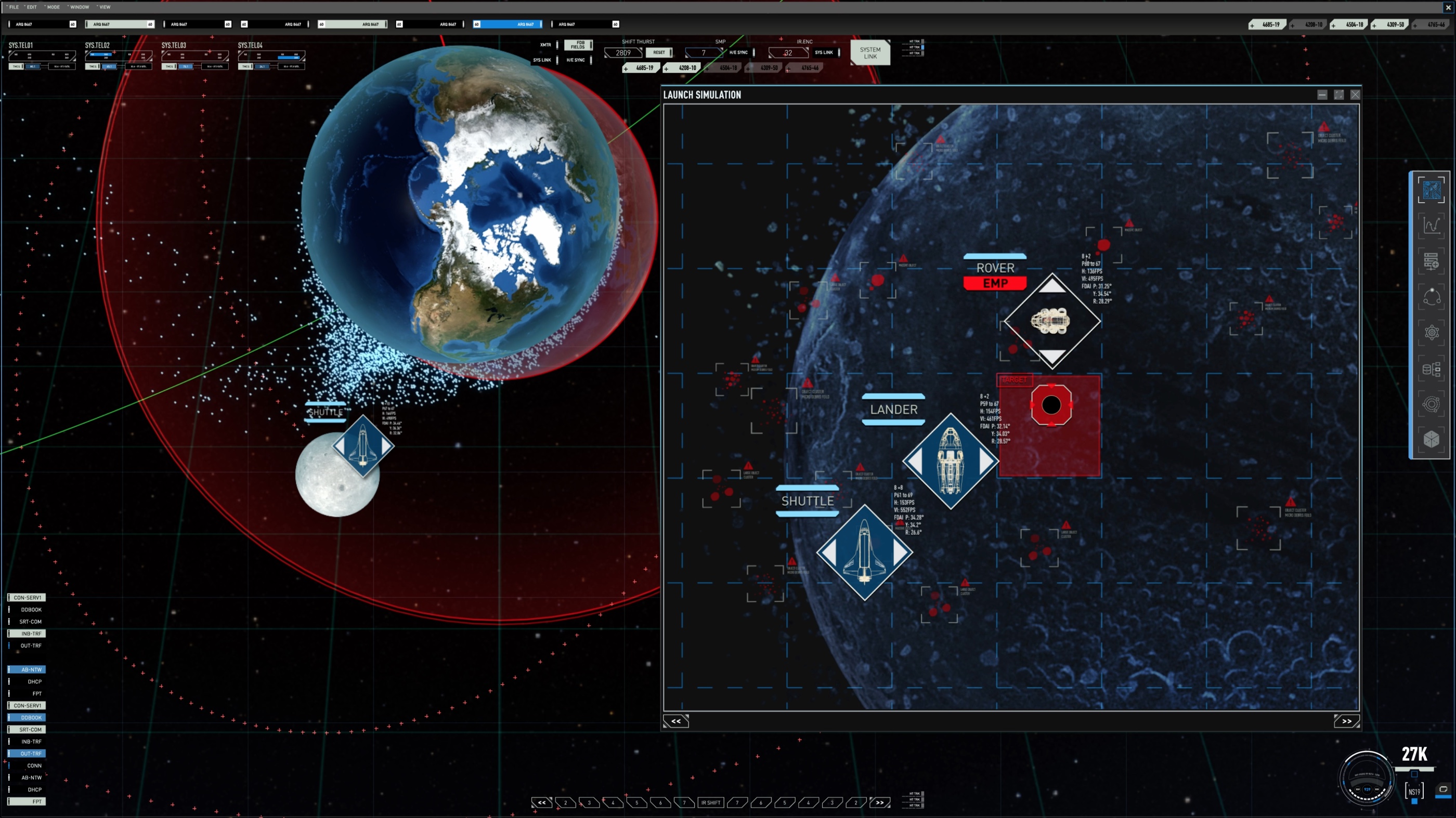

Screen graphics for the loading simulation on “Moonfall” by Clark Stanton.

Kirill: Do you have a preference to work on set versus in post?

Clark: I personally like to build the graphic for set. It’s more fun to play with the dynamic timing. You don’t know how the actor’s going to read their lines, or how much they’re going to pause or emphasize something or play up the drama. Having the reference there for them so that they can point to the screen or read the screen or react to it is much more enjoyable for me.

That said, there’s so much more freedom in post. You know where the edit’s going. You know exactly what you need to see. You usually have a little bit more time on post to get those creative answers and have the attention of the director or the producer. You can play with that part of the story a little bit more precisely.

Kirill: Is there a particular set of skills a person needs in order to not get burned out?

Clark: As a person that’s a workaholic by nature, I think that you need a hobby that isn’t in front of a screen. I’ve always played video games. I’ve always loved creating my own art. This industry has taught me that I need to stand up more and get away from my desk, and that’s my main advice to somebody that is going to try and get into this industry. Make sure that you have a good hobby that you can disconnect with. This industry is feast or famine. You have to take the jobs when they come, sometimes they overlap, and that’s a recipe for burnout.

I personally lift weights, swim or go biking. That has definitely helped me to come back fresh and creative for the next project.

Kirill: There are different names to this industry – playback design, screen graphics, fantasy user interfaces. Do you have a preference on which one best fits what you do?

Clark: Screen design or playback graphics is more how I associate. FUI comes in a lot more when you get into some of the cooler, more post fantasy projects, where you get to explore a holographic HUD in Iron Man or Spider-Man. They’re all applicable. I favor playback, so I tend to lean that way. But if you’re talking to a layman, they might only recognize FUI because of the nature of press coverage for the more recognizable projects.

Kirill: Putting on that layman’s hat, how do you tell me what your job is and why it’s needed? I have my layman’s phone in my pocket and my layman’s computer at home, and those have plenty of user interfaces already on them.

Clark: The easiest way I get it across to people is through cues. If a director wants you to start from the middle of the scene, the actors need to remember where they were, and then continue that scene from the middle. Now, if they have real phones for texting back and forth, you’re interacting with those messages. What happens when it’s a reset? Props has to run in and delete all those text messages, but also to reset the phone time because it’s been 5-10 minutes since the last take. That’s one aspect of it – replayability and manipulation.

The other part is the legal aspect. If you have a villain, Samsung or Apple probably don’t want them to have their product in there for the bad guy. Creating fake interfaces allows you to get around legal clearances.

Screen graphics for the lander cockpit on “Moonfall” by Clark Stanton.

Continue reading »

Continuing the ongoing series of interviews with creative artists working on various aspects of movie and TV productions, it is my pleasure to welcome back Tom Hammock. In this interview, he talks about the scope of blockbuster franchises, building physical sets and things that are still missing in digital worlds, traveling the world to make movies, and the rising of generative AI tools. Between all these and more, Tom dives deep into what went into making “Godzilla vs. Kong” and “Godzilla x Kong”.

Kirill: What happened to you since we spoke earlier last year?

Kirill: What happened to you since we spoke earlier last year?

Tom: Well, we made a movie called “Godzilla x Kong”, which was great. And there’s another one that I just finished with Zach Cregger who directed “Barbarian” in 2022. But really the big thing was Godzilla, and as you can imagine, it took a long time to make that movie.

Kirill: One thing I couldn’t figure out is how to say the name of the movie. Is it “together with Kong”, “against Kong”, something else…

Tom: It’s tricky to figure out. I know they tried a lot of titles, and “Godzilla x Kong” worked in the wrestling sense, in terms of them teaming up. That was always the goal. We knew we wanted to do the “versus” film and then the “team” film.

Kirill: How many previous Godzilla and Kong movies have you watched?

Tom: Adam and I watched pretty close to all of them, genuinely. When we started “Godzilla vs. Kong”, Adam had a little TV in his office, and he scoured the internet for VHS, laser discs, anything he could find. He would play them constantly, and we’d come in and reference scenes. It was an interesting process. I’d say that I’ve seen big chunks of the majority.

Kirill: Are we talking also about the 30-odd Japanese ones?

Tom: He was able to get his hands on pretty much all the Japanese films, and another seven or so King Kong variants from around the world. We put in our time. You see little Easter eggs sprinkled through. Every once in a while, there will be something.

Kirill: Did you know that there was “Godzilla Minus One” happening roughly around the same time?

Tom: We did. It’s similar to when “Godzilla vs. Kong” came out, we had a sister movie, which was “Shin Godzilla”. Toho and Warner Brothers Legendary talk a bit and plan things out, because it’s not just the films. You have the trailers, you have the toy releases, you’re trying to build the excitement. Also, Takashi Yamazaki and Adam Wingard are friends.

On the sets of “Godzilla x Kong”, courtesy of Tom Hammock.

Kirill: How was your experience going from the smaller art department on “X” and “Pearl” to this huge machine?

Tom: It’s a crazy change in scale, but in some ways it’s the same experience. You have your base camp, and you make your way through all the trailers and all the equipment. And at the end of the day, it’s still two people talking in front of a camera, which is the same as “X” and “Pearl”. But in other ways, Godzilla is so different.

On “Godzilla x Kong” we could go to literally an island to build the Monarch base on the beach. We had had the resources to do that, to get that level of in-camera work – which was fantastic and a ton of fun. Budget goes up, but expectations go up too.

Continue reading »

It’s been seven weeks since Mark Coleran has passed away. That morning I opened my Facebook stream to check in on friends’ vacation updates and occasional neighborhood rants, only to be greeted with the short notice that Mark is gone. At the time, Mark was living in Sweden, traveling the country, taking photos of anything and everything that caught his inquisitive eye, and posting daily updates on Facebook and Instagram. He was also working on something secret for Volvo, but he never really talked about it. And now we’ll likely never know.

It’s been seven weeks since Mark Coleran has passed away. That morning I opened my Facebook stream to check in on friends’ vacation updates and occasional neighborhood rants, only to be greeted with the short notice that Mark is gone. At the time, Mark was living in Sweden, traveling the country, taking photos of anything and everything that caught his inquisitive eye, and posting daily updates on Facebook and Instagram. He was also working on something secret for Volvo, but he never really talked about it. And now we’ll likely never know.

Back in 2011 when I started doing interviews on computer interfaces in movies, I did not know his name. And yet, almost every single interview I’ve done in those early years mentioned his name, either as a mentor, or as a source of inspiration. From 1999 until 2006 he worked on every single blockbuster action movie that you can think of, from Bourne to Mission Impossible, from Tomb Raider to The Island, and many more. He was the first to admit that he did not start this field, but he undoubtedly revolutionized its ascendance into what it is today.

As he moved on into the world of “real” design, first with Gridiron Software and his work on the unfortunately short-lived Flow, and then later freelancing on a variety of projects, and as his name kept on popping up in the interviews that I was doing, I finally reached out to him in 2016 to have an interview about his film work, and his transition to be outside of that industry. As fate would have it, we did not move on to fully review and publish it that time.

But I remained hopeful that we would have another chance, and it eventually happened in 2021. One of the best things about Mark is how unreservedly honest he was, even when he knew that it landed him in a good deal of trouble with some of the people he worked with. And the other brilliant thing about him was his pragmatism. Summing up more than two decades of being a professional designer at that point, Mark got straight to the point:

We care about what we do, and it’s easy for us to become obsessively caring about something. We think we own it.

People will hate me for this, but for me it boils down to this. If you’re doing art, you’re doing it for yourself. If you’re doing design, you’re doing it for somebody else. You don’t get to make those decisions. We really do care about this, but you do have to have a very high level of pragmatism, almost down to a cynical level of detaching yourself from it. Somebody’s paying me to do this job, so let’s get the job done. But it’s not mine.

You don’t have to be aloof. I care about what I do. I want it to be good, and I want it to work well and to do what it was meant to do. But I focus more on my craft now than on the individual objects themselves. Did I do this well? Have I learned something new by doing this? Did I save some time by trying a different approach? It’s the craft that I now get the pleasure out of, and not necessarily the end result. It becomes a hard lesson. When I left the work, it was because I did actually care about that. I was getting so annoyed by what I was doing and how it was looking like on screen. We do this work, and then it’s there for a couple of seconds on screen. It doesn’t feel like it’s worth it.

That’s why I went into the world of real software. In that world, every decision you make affects how that thing works. It affects the experience somebody has. It’s continuous as well, as you refine it, iterate on it, and build upon it. And my experience in real software is the same. Nobody cares. Nobody sees what you’ve done. They all complain about the stuff you did badly, but in the end it doesn’t really matter. It’s out there, and it’s being used, and you don’t own it. A hundred other people had their fingers on there, and you did your part, and it’s exactly the same as movies.

I’ve started my professional career as a software engineer back in 1999, right around the same time as Mark did. These days, I find myself in much the same place as Mark when I think about my work. I am given certain tasks to deliver, each task determined by the needs of the product. It is my job to deliver a high quality output that does what it’s supposed to, in service of the product.

I spend most of my time thinking. Contrary to how our field is portrayed in the movies, we don’t furiously type away at the keyboard for hours. We don’t have a grid of high resolution monitors, with multiple dashboard, text editors, terminals and other windows racing against each other with ever more information to be parsed. I think deeply about the task at hand. I spend my time constructing an abstract representation of it in my mind. I hold it, and I look at it from different angles. I think about how the final thing should look like. Not for myself, but for others that will be using it.

I care deeply about delivering a thing that works well. At this point in my career I can say that I know what I’m doing, and that I do it well. We are paid well for it, but it’s not just the money. Being able to hold a complex problem in your mind, to look at it from different angles, to consider possible solutions, and to choose the most promising initial approach is its own reward. Being able to put those ideas into hard code, and to see that code running and doing what you intended it to is its own reward. Taking pride in being good at what you do (removing the mandatory sense of self modesty from it for a second, if you don’t mind) is its own reward. Without all of these, you spend 50 hours a week, 50 weeks a year, a 45 year career – literally half a lifetime – following somebody’s orders to maximize the mythical shareholder revenue. It is absolutely soul crushing.

And at the same time, I used to have this undertone of something that was missing. It’s a bit selfish, but then, we are always at the center of our own world, from the moment we wake up until the moment we drift away into the nightly sleep. Validation and approval. To have others congratulate you on the job well done. To need it to come from the outside. To question yourself and your ideas, your ability to do this well, and the quality of your work – when all you see from others is indifference. I’ve lived with that for years, until about three years ago, when I talked with Mark. My last question for him was on what piece of advice he’d give to his own younger self, and this is what he said:

I would say that nobody else cares about the things that you care about. You like what you do, you love what you do, it’s important to you, but it may not be important to anybody else.

That difference can be the source of a lot of frustration for a lot of designers and creative people. We’re not necessarily doing what we think we’re doing. We’re always doing something for somebody else. And half the time, we’re just going to be doing the thing that they want and not having any input at all. Understand that you’re not as important as you think you are.

It’s a strange thing for me, because there’s this myth that has grown up around me [laughs]. I’m this mythical FUI beast that did that work, but I’m just a person. I’m just a designer. I was working with somebody recently, and they said that they thought I’d be quicker and get this stuff done in a day. But it was two weeks worth of work. So the idea of who you are and what you are can be different to other people as well. Be clear about what you’re doing, who you are, and why you’re doing it.

Understand it’s all just a job. Everybody wants to treat design and creative work like it’s something special, and it is to you. But it is just a job as well. Do not forget that you are just doing something as a job. I’ve worked way too hard and way too long on stuff that nobody cares about it, because I forgot that. It didn’t matter if I done 8 hours a day or 16, but because I did 16, other things suffered. So don’t forget it’s just a job, and you’re not as important as you ever think you are. That’s the one thing I really wish I’d learned a long time ago.

It’s been almost three years. There’s not a week that goes by without me coming back to this passage. It changed the way I see my own work. It changed the way I see the work of others.

I never thought to thank Mark for that interview, beyond the usual appreciation email I sent to him after it was published. I never thought it would be the last time we spoke. I never thought that he would be gone so soon.

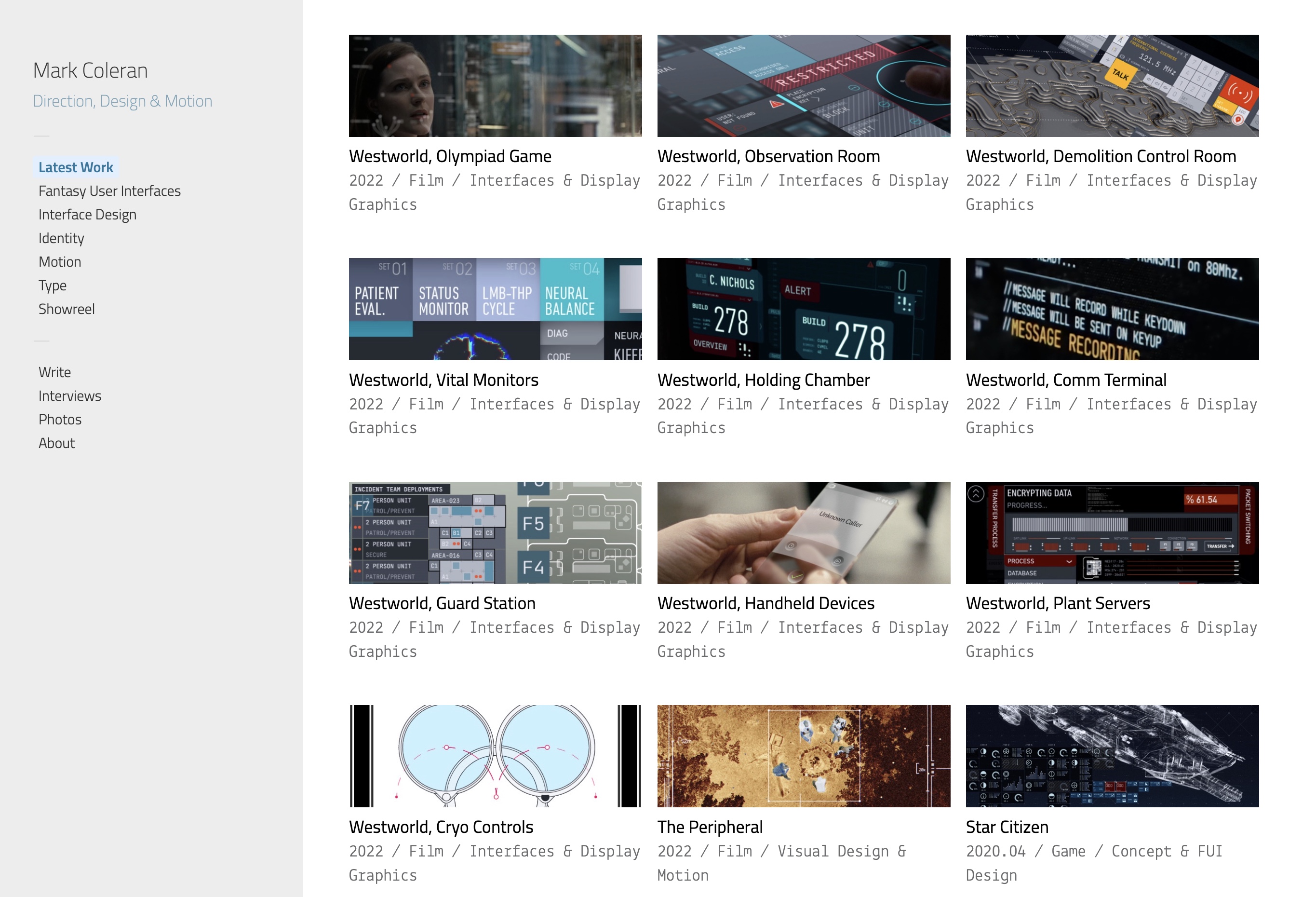

After Mark passed away, I found out that his portfolio site was taken over by some online scammers that are now hosting a casino cashgrab. It pains me that we don’t really have any good way to dispute such a takeover. It pains me that we don’t really have any good way to preserve somebody’s legacy online in the same place they had when they were alive. But I knew immediately that Mark’s legacy needed to be preserved.

I’ve spent these last seven weeks reconstructing Mark’s portfolio from the wonderful Web Archive, and extending it with more of his work that he has done in the last decade or so. Although it was his decision to put some of his later work on Behance and ArtStation, I feel that all of his legacy deserves to be celebrated and commemorated in one place. I can only hope that Mark would agree.

This is where you can find it. It is a reconstruction of his main portfolio, with the following additions:

- All recent work from Behance, including his comeback to the world of fantasy user interfaces in season 4 of Westworld.

- The work that he shared with me for our interview.

- Articles, interviews and presentations going all the way back to 2007. I wish I could have done more here, but a big chunk of those have either been lost forever, or are locked behind conference paywalls. I have a lot more to say here, but this is not the right place for it.

- Photos of Mark from his Facebook friends.

As long as my site is up and running, this tribute to Mark will be accessible online.

Mark, I can’t thank you enough for finding the time back in 2021 to do that interview. I wish I would have reached out after we did it and met you in person. And now that moment is gone forever. All I can feel is a deep appreciation for what you’ve achieved in the last 25 years, and a profound sadness about all the future things that could have been. Rest in peace.

Mark Coleran

14 September 1969 – 14 June 2024

![]() Kirill: Please tell us about yourself and the path that took you to where you are today.

Kirill: Please tell us about yourself and the path that took you to where you are today.![]()

![]()