The Band Perry’s “If I Die Young”, LeAnn Rimes’ “Probably Wouldn’t Be This Way” and The Secret Sisters’ “Tennessee Me” are some of my favorite music videos in the last few months, and imagine my delight to find that they were all directed by the same man – David McClister. I’m very honored that David has found time in his busy schedule to answer a few questions I had about the art and craft of directing music videos, and to delve deeper into the particulars of some of the videos in his portfolio.

Kirill: You’re a photographer and a music video director. Tell us a little bit about your background.

David: I studied English and Art History in college. We didn’t have a film program there, so it was the closest I could come to actually studying film. Both disciplines have served as great backgrounds for film making and music videos – the English background for writing treatments, and the Art History background for concepts and inspiration. I started out as a film maker first, then at my wife’s encouragement, I began approaching some of the artists that I wanted to work with that couldn’t afford to do music videos. That’s when I picked up a still camera and started shooting stills and fell in love with it, especially the spontaneity and level of intimacy you have with the artist. I’ve been doing both mediums for about 10-12 years now.

Kirill: Let’s talk about the creative process behind music videos. What is your interaction with the performer to define the story and the look?

David: Each project is different. In a typical process, the director will be sent the song, along with an idea how much money they have to spend, and often an idea where they want to shoot – depending on their touring schedule, where the artist lives and so forth. Sometimes they’ll have an idea of the creative direction – do they want a performance-driven piece, a narrative-driven piece, or something totally different from what they’ve done before. So a lot of times they’ll give you a bit of an idea of where they’re thinking they want to go with it.

On my side, what I typically do is download the song and go to a very quiet, often dark place, put on the headphones and listen to it, keeping in the very back of my mind what they think they might want to do. The record label, the artist, the management may have ideas on where they think they want to go with this particular video project, but you never know where the music is going to take you creatively. Once you have the idea, that’s part one. The second part is to write a treatment, and that can take very little time, or it can take days. Sometimes it’s very easy to put into words exactly what you’re thinking, and sometimes it’s a little bit harder to describe your visions.

Kirill: Is a treatment some kind of a story board with sketches of different scenes?

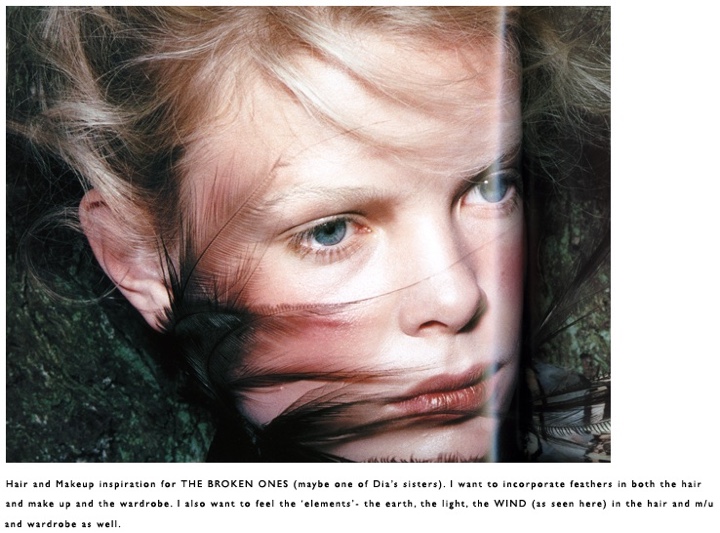

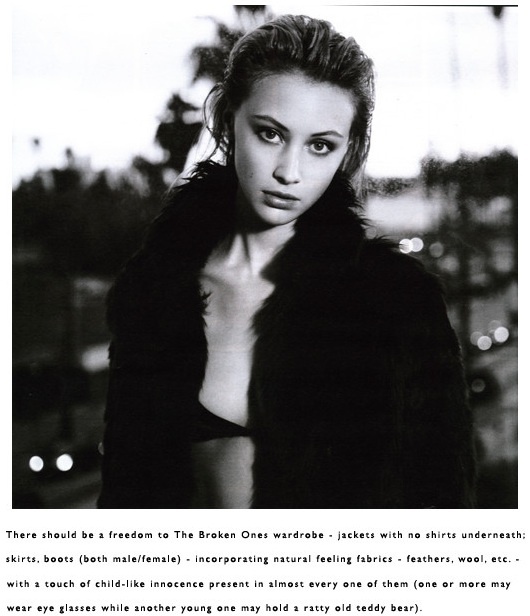

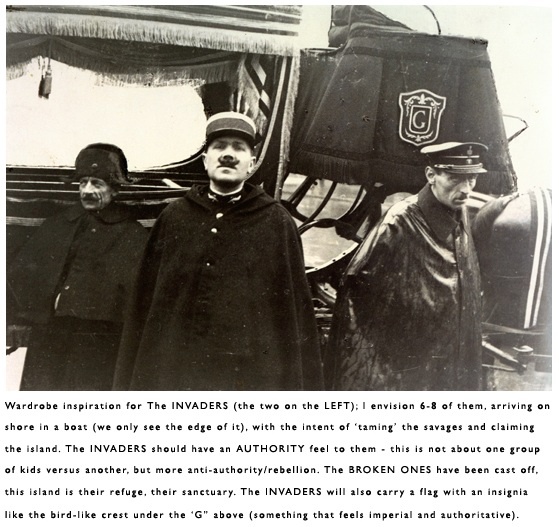

David: It’s very open to how a director wants to present it. I think the more visual the presentation, the better. You have to keep in mind that not everyone that is going to be looking at the treatment is a visual person – so you should try to be as specific and visual as you can to show them what you’re thinking, from hair and makeup to production design to photography to wardrobe to props. It could be anything that is key to your idea.

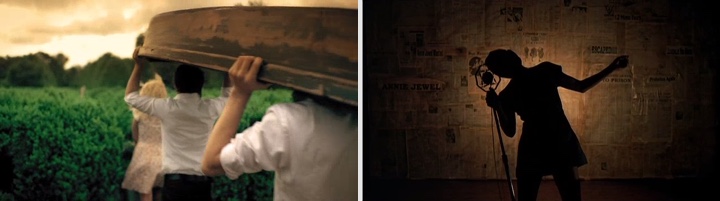

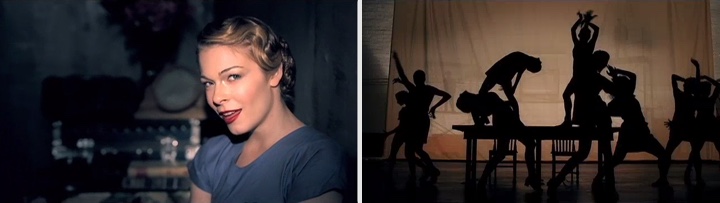

Top – treatment proposal for Dia Frampton‘s “The Broken Ones”. Bottom – still from the final video.

Typically it’s one to three pages of text, and then some visuals to go with it, and hopefully that gives them a strong idea of what you’re seeing in your head. The video that I just shot last week in Los Angeles is for a song that I fell in love with, from an artist named Dia Frampton from the last season of “The Voice”. When soliciting treatments for her song, Dia shared several links to past videos that she really loved that she wanted all the directors to have a look at. The record label and management also had some notes on what they thought they wanted to do with the video. But I felt so inspired by the particular song and so strong about the idea that came up with, that I went with that. It was totally not what they said they were looking for, but I got the job.

I guess the lesson I’m trying to make is that if you’re passionate about your idea, you pursue it. You go for it, and hopefully that passion comes across in your presentation.

Kirill: You worked with LeAnn Rimes and The Band Perry on multiple videos. Do they get more open to your ideas and trust your direction more after the first collaborations?

David: Definitely. The comfort level grows, the confidence level grows, and I think there becomes sort of a shorthand between you and the artist. You tend to really know each other, to know each other’s likes and dislikes. The process becomes very unspoken, the same as when you work with the DP [director of photography] or production designer on several jobs. Plus, the more you work with the artist, the more you see the potential, their strengths and weaknesses, and what you can do to take them to a different level. You see things on set – production-wise or performance-wise – and you think that this will be great to explore later on in another video down the road. And of course you’re always sharing ideas, even when you’re not working on a job together.

And to the credit of both artists that you’ve mentioned, LeAnn and The Band Perry, they’re constantly trying to reinvent themselves, to push themselves to do concepts they haven’t done before, to show new sides to their fans, to keep it fresh and to continually challenge themselves. They’re not only doing it musically in the studio, but they’re also challenging themselves visually, to try things that might be a little bit outside their comfort zone.

Kirill: How big is a typical production in terms of your crew?

David: It depends, obviously, on the budget and, kind of hand in hand, on the idea behind it. The bigger the budget, the bigger the artist, the more people there are involved, and there will also be a lot of media there covering the video itself, so it can become a pretty huge event. I did a video a couple of months ago that was very low budget for a song I really loved, and it was more of a photoshoot, with less than ten people on the set. And the one last week with Dia, because of the excitement about the project and “The Voice” we had around 40 people with cast, crew and all the extras.

Kirill: How much time do you have to shoot a video?

David: It’s hard to get multiple days for shoots anymore. Typically they’re almost always single day shoots, and you’ve got an average range of 12-14 hours to shoot it. Depending on the idea and budget we can have a single camera or multiple cameras. Oftentimes I’ll employ multiple cameras if I can pull it off, just to get more coverage and to keep the day moving, and to get as much variety as possible. To me, you want all the images to be beautiful, but you want a great variety to keep the audience interested for the full three or four minutes. You need to be consistently showing something new, some new information. I don’t think you can show the audience everything in the first 30-45 seconds and expect them to be as engaged three minutes later. You need to be consistently creating something new for them to look at.

Kirill: And how long is the post-production stage?

David: Part of that depends on the format you are shooting – if it’s film, you probably didn’t shoot more than a couple of hours of footage – so 2-3 days possibly on the first cut. If it’s digital, you might have shot several hours of footage, which is obviously a lot more for the editor to look through. In that case it might be a week before you have a first cut ready to show everyone.

Kirill: There’s a lot of attention to details in your videos. Does this go back to capturing the viewer’s interest and have them go back to watching the video again and again?

David: I think that’s the key. As the director you have to keep in mind that the fans, even the casual ones, are going to watch that video numerous times. To maintain that attention, to keep their attention and focus you need to have a lot of depth, a lot of layers to your video, and to pay a lot of attention to the details throughout. It goes beyond the props, the framing and the editing. It needs to be multi-layered, and hopefully each time they watch it, even many views later, they’re picking up little details that they didn’t pick up on in previous viewings.

Kirill: And on the other hand, there’s a certain fleeting aspect to a music video. In a few weeks there’s the next song, the next album, and people don’t go to a music store to buy a DVD with that video.

David: I don’t think it’s as fleeting you might believe. What amazes me is I will still get comments from an artist or someone about a video that was done years ago that made a strong impression on them. I think videos, even though they tend to come and go fairly quickly on broadcast, have a lasting impact on the audience. I know that when I listen to certain songs, on the radio or in my home, I find myself watching the video in my head – but then I’m a director, so maybe it’s part of it. But I think in general it stays with people even more than photography, which is an image that you can hold in your hand – unlike video – but there’s something about video that connects with an audience that really makes a lasting impression, something that people think about years later that stills have a hard time competing with.

Top – treatment proposal for Dia Frampton‘s “The Broken Ones”. Bottom – still from the final video.

Kirill: With music programming practically disappearing from MTV and VH1, once mammoth conduits of music videos, a large swath of the audience gets new videos from YouTube and other streaming sites. Do you still plan and construct your sets for high-definition, high-quality capturing?

David: Well, I grew up when MTV was still playing videos, and that’s how I discovered so many artists. FM Radio wasn’t the answer either, so the only way I could discover new music was on MTV. So it is sad that it has changed. There were so many incredible videos that came about because of that.

With the Internet, YouTube, iTunes, being able to download videos – it’s a new dawn. I think people are very much into music videos again, and they have been for several years now. There was definitely a period after MTV and VH1 changed their programming to be all content, and before Internet took hold and the music business knew how to use it, that there was a real down period with music video. But it’s back, there’s a real buzz about it. Unfortunately most people only see it on a small screen. I still prepare my shoots as if they’re going to be on a big screen.

Probably the main difference with videos now comes from shooting primarily with digital cameras. The more we see the digital formats, which have different look than 35mm or 16mm film, we as an audience become more accustomed to that look. I’m not saying it’s a good or bad thing, it just is what it is. It’s just the nature of an evolving medium.

Top – treatment proposal for Dia Frampton‘s “The Broken Ones”. Bottom – still from the final video.

Kirill: What happened after that down period? Do you see bigger budgets, do you see artists pushing to shoot more videos from a single album?

David: I don’t know that it has changed that much. The music business has been through a difficult time over the last several years. As far as the music videos and photo shoots, the budgets aren’t where they used to be. But the creativity level has not changed, and it’s more challenging now with limited budgets.

Kirill: There’s an almost cinematic quality to your videos, with so much attention to focus, framing and lighting. It feels like I’m watching a small movie. Is this something that you insist on doing when you’re negotiating with the artist and the label?

David: At a certain point you have a body of work and a style that the artist, the management and the record label all know. When they come to you, they kind of know what they’re going to get, in a sense. My approach is pretty consistent in all the things you’ve mentioned, and this is just how I see things.

Kirill: There’s a certain style to shoot a video where the song takes an almost back stage to whatever story is shown, and the main attention is kept on the actors playing out that story. All your videos place main emphasis on the performer. Is that a conscious choice?

David: I never really thought about it. I think it’s incredibly poweful and cinematic when you have an artist giving a very strong, emotional and honest performance. There’s something about it that resonates with the audience, and if you have an artist that can really pull it off and the right song, there’s no need to cut away from that.

Kirill: Has it ever happened that a certain look or a set that you’ve created for a video affected the tour stage setup later?

David: Yes, I’ve been told that. I know that it’s happened with LeAnn, and it’s happened with The Band Perry too. They’ve been so happy with the choreography and the set, that they took it to award shows and on the road. It’s very rewarding that your work is being carried over to that level.

Kirill: Let’s go back to keeping the audience interested throughout the entire length of the video. Oftentimes you present us a story that happens in the background, cutting back and forth between figments of it, presenting a puzzle of a sorts. Do you feel constricted by this very short time frame, and by not being able to actually put that story into a spoken word?

David: Actually I feel the opposite, I feel like I have a lot of freedom. If you talk about a puzzle, I try to make most of my videos to be like a film, to have a conflict, to have a narrative arc, to have a payoff at the end. Hopefully, for the audience, the resolution is not the one you expect. For example, with Lady Antebellum “Need You Now” video, most people expected to see the two lead singers get together, but they ended up with two different people at the party at the end of the video. I wanted it to have a bit of a twist, something unexpected.

Kirill: While this video was a more literal interpretation of the lyrics, LeAnn’s “Nothin Better To Do” is a more loose version that captures the mood of the song, but takes it to a more open-ended visual journey.

David: Being literal is pretty boring, it gets very old to show exactly what the singer is saying on record. Obviously there are times when a song demands it, but in most cases I find it boring, and hope to reinterpret it in a different way. It can be the setting, the characters, the time period, the look of the film – and hopefully something that when you listen to the song as a fan, you thought it was going to be one way, and when you see it, you’re pleasantly surprised that it’s something that you hadn’t expected, and you enjoy it and have fun with it.

The particular video you’ve mentioned was a lot of fun. It’s actually a character that LeAnn had in mind when she wrote the song, a distant family member. And so we were able to take that as our inspiration and build around it, and it was a very long shoot, about 18-20 hours in a single day. It’s still performance-driven, an homage of sorts to the great director and choreographer Bob Fosse, and very much like a movie.

Kirill: Let’s talk about “Tennessee Me”. It has a lot of jumps, camera shifts, focus shifts, and feels like an unearthed home-edited piece stitched together from multiple reels.

David: We did almost all of it in camera. We shot on a 35mm camera (An Arri 435), and we tried pretty much everything you can possibly imagine with it. We changed camera speeds in camera while we were shooting, we would go forward and backward at times – and that’s how you get the double exposures. They were not layered in post, but rather in camera. And the overall effect, as you said, is that I wanted it to feel like a found film, an amateur film in the way it was photographed by a friend of family member many years ago, left in the attic and then found years later and played on a home projector. That was the intention of it, and that’s how we photographed it.

I liked that they allowed us to keep some scenes out of sync, where the voice didn’t match up perfectly with the picture. There were several instances where that happened, and always by the end of the shot it’s back in sync, but there are moments when it’s out of sync, lending itself to the amateur home film feel, like it was cut and spliced together on an old film splicer.

Kirill: And you can do this only once

David: In a way yes. You can definitely take some of the things that you learned and apply them to other jobs, but you don’t want to repeat yourself and do exactly the same thing. The original inspiration for the look was going to be toned black and white ambrotypes. Then, as we were shooting it, the girls looked so amazing in color that I changed my mind and we ended up toning the color film to a bit more of a hand tinted look. I have had the good fortune to work with a colorist in San Francisco named Chris Martin who has worked his magic on many of my transfers.

Although I couldn’t be there, I sent him several references and we talked on the phone about the shoot, the concept and the overall feel I was going for. He ended up transferring it about six different ways. The intent was that different sections of the ‘found’ film would have aged differently over time, and then been spliced together to make the film.

Kirill: And then you have “Hey Mama” by Mat Kearney where it looks like you just grabbed the camera and started following the guy on the street.

David: It was sort of an homage to a collection of documentary photographers that greatly inspired me over the years, Danny Lyon, Robert Frank, Bruce Davidson, Susan Meiselas – all phenomenal shooters. We shot it in New Orleans on 16mm black and white over the course of two long days using all natural light. Some of the people were cast, and others were just pulled off the street for a few minutes. I can’t say enough about how great it was to shoot in New Orleans and how wonderful everyone was to us while we were down there. I think the idea worked really well with that song, and Mat did a tremendous job.

Kirill: Film camera, all natural lighting, constricted time limits. Did you actually have time to look at the raw footage and make some adjustments or corrections?

David: No, as it was film, there was no way to go back and look at what we had shot. We actually didn’t have a monitor to look at either, but I had a good feel after each scene about exactly what I had. I had a very detailed shot list, and kept a mental note of what we were getting.

Kirill: And then, as an almost diametrical opposite, “And It Feels Like” from LeAnn Rimes with explosion of color, wide swaths of pinks and magentas, soft focused crystal chandeliers and richly decorated interiors.

David: We shot it in 35mm anamorphic, and I remember I was drawing inspiration from films of Stanley Kubrick, specifically Eyes Wide Shut. Norman Bonney was the director of photography and he did an amazing job. I told him during prep that I really wanted to push it color-wise, to be really bold. I wanted each room to have a different color, a powerful color wash. So I gave each room in the house a very dominant color theme, from the performance room where it’s all pinks and purples, to the study where they’re having pre dinner cocktails which was heavy yellow, to the dining room that was heavy red where things don’t go as she expects them to go when her ex lover shows up to the party with someone else on his arm. The colors were set to enhance the emotion of the scene, and I think it works very well.

You go in with a very concrete set of ideas when you write the treatment, but it’s a very fluid process. You’re consistently changing throughout the process – the pre-production, the day of the shooting itself, post – you see what works, what doesn’t work and have new ideas that continually come up during the process.

In the treatment for that specific video I did not say that I was going to have such a heavy color wash. The pitch was all about the narrative storyline. Once I saw the location, and the more I looked at it, it just sort of happened.

Kirill: Does it happen that you watch a music video done by somebody else and think to yourself that you would’ve done it in a completely different way?

David: No, I never think that. I don’t watch a lot of other videos. I tend to draw inspiration from films, photography, painting and so forth.

Kirill: Do you see yourself branching off into longer formats, documentaries, short movies or full-length features?

David: Definitely. I just finished a short film about six weeks ago that I’m very excited about. I’ll be submitting it to festivals in the coming months and have several more shorts that I’m prepping to shoot in 2012. I think every music video director has feature film aspirations, and I’m certainly no different.

And here I’d like to thank David McClister once again for his great work, and for this wonderful opportunity to glimpse into the world of directing music videos.

What happens to a movie after it is made? How do you preserve a piece of cinematographic history for decades to come? After talking to a variety of creative artists – cinematographers, production designers, art directors and others – it’s time to take a deeper look at the distribution, exhibition, projection and archival side of things. Kyle Westphal is the Chief Projectionist at the Dryden Theatre, George Eastman House and the co-founder and Vice President of the Northwest Chicago Film Society. Kyle has graciously agreed to share his thoughts on the history, present and the future if his craft. In this conversation he talks about the transition to digital projection, finer points of physical and digital archival, the long tail of streaming services and the effects it has on film restoration,and the tumultuous transformation happening in the movie industry in the last decade.

Kirill: Tell us about your background and what drew you into the profession.

Kyle’s headshot courtesy of R.F. Hall

Kyle’s headshot courtesy of R.F. HallKyle: I’d been interested in film since my early teenage years, and while at that point I wasn’t sure what the outlet would be–making films, being a critic or something else–my options were fairly limited. I lived in Sacramento, which had little industry presence and no cinematheques. My interest at that point, by necessity, was film as text, film as a conveyor of tone, plot, irony and style.

It was not until I was at the University of Chicago that I discovered other, essentially material, ways of relating to film. I became involved with the Documentary Film Group at the University, which has been around since 1941 and is the longest continuously-operating film society in the US. It’s a repertory house which also does second run new releases on the weekends, catering to a broad and diverse college audience. They showed eight movies a week, some of them multiple times, and there was the possibility of becoming an apprentice projectionist for an academic quarter. The projectionist showed us everything – inspecting, threading, running the machine.

After apprenticing for a year and becoming a projectionist, I took on other responsibilities at a few different places around the town. I was becoming interested in the idea that there is more to film than an abstract notion, that it exists as a physical thing, a 35mm motion picture print, and there are a lot of skills and craft involved on that side. The people who work in the depot that send you the print, the courier who ships the print, the curator who books the print for your venue, the inspector, the projectionist–it made me feel connected to film in a way that I didn’t know was possible.

When I decided that I wanted to do this professionally, I felt that I understood fairly well what happens when you get the print and it hits the screen. But the other part–how the print was made in the first place, how you take a negative and make the print from it, how you take disparate nitrate materials and restore fragments of a film to something that resembles the original–seemed the next logical step. And so I came to the George Eastman House and its L. Jeffrey Selznick School of Film Preservation, where you attend lectures on these topics and apprentice the various aspects of an archival institution–cataloging, curation, preservation, projection.

Kirill: You went well beyond taking a print and projecting it in the theater.

Kyle: To an extent, it is still technical. You have to understand what materials you’re working with, what is technically possible in terms of restoring and preserving them. If you’re dealing with analog material in the conventional photo-chemical route–sending a negative to the lab to do the fine grain, dupe negative and print–you have to understand what the lab specializes in, their equipment, and human talent. If you’re talking about digital material, then you’re asking how we can scan the material–a telecine or something higher resolution–and play with it digitally to correct color and density.

It’s also political and cultural. It’s not simply a matter of money falling from the sky, and archives being able to point at a can in their vaults and say, “This is what we’re going to preserve today.” You write grants, maintain a public presence, and make arguments for what is valuable about your collection. You have to have some sense about why these things are culturally important, make those arguments, and have both discretion and discrimination to make a bid for what’s important.

Kirill: What is the level of public interest in repertory theaters?

Kyle: I don’t know if you can talk of there ever being the golden age of repertory programming. In terms of sheer numbers of people having access to and seeing these films, you can say that the 1970s were the “golden age.” There were film societies on every college campus in America, and there were a lot of people showing second run and repertory movies in 16mm prints. It was a widely disseminated and readily available medium, well beyond the college campuses, actually–in churches, union halls, community centers.

On the other hand, you can say that they were dealing with a substandard format, and one that falls outside the modern definition of repertory cinema–brand-new 35mm prints on a big screen with professional equipment. And to play devil’s advocate again, the distribution and demand arising from film societies resulted in a wider circulation of 16mm material. There were things that you could get a 16mm in 1975, and you can’t get a 35mm print, DVD or Blu-ray today. Standards have never been higher, there’s never been more conciousness; studios have never supported 35mm and restoration to the extent they do today, but that does not translate directly into broad availability and range.

When you run a theater, you always wish that the attendance was higher. But if you’re asking whether there is still an enthusiastic audience for repertory, I would say yes. Actually, this whole matter of film and there being a physical thing in front of you–the film strip and light going through opaque emulsion, and the understanding that what you’re seeing is not a result of zeroes and ones, but rather light interacting with physical film–there’s a lot of potential for it to be an experience, a particularly appealing aesthetic, especially in the age when most media consumption is through some digital intermediary.

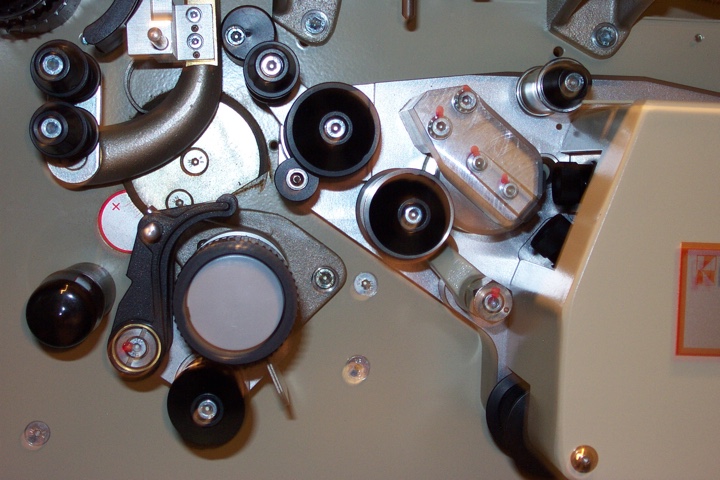

The Eastman 25–a robust, exhibition-grade 16mm projector.

Kirill: What are your thoughts about the transition to digital?

Kyle: It’s a different way of making images, and I don’t want to judge which is doing a better job. And all the talk about high-definition–2K cameras or Blu-ray with 1080 lines of resolution–it’s high definition in relation to standard broadcast and DVD. It’s certainly not higher definition than film.

Grain is not an artifact in film, grain is the film, grain is the image, grain is the way that we’re able to understand what it is we’re seeing. I wish everyone could have the experience of seeing a print made direct off a camera negative with no intermediaries, to see how film stocks of 80 years ago are incredibly luscious and detailed, and have a certain physicality that digital lacks.

This is not to say that digital doesn’t have a place. When you’re shooting in low light, or you’re going for a certain kind of realism or naturalism, without the intervention of so many lights, digital does something. You look at “Public Enemies” or any other recent Michael Mann film, and there’s an aesthetic that is not trying to imitate film, but rather trying to chart a new way that the characters move, a way that cuts make you feel, a way that landscapes have certain solidity – a way that is very distinct from film.

They are different systems with different advantages. I would hate for film to go away. When you look at the history of the 20th century, it’s the history of film, it’s the history of not only narrative films, but all the ways that people expressed themselves–whether it be home movies, industrial or sponsored films, newsreels, television footage shot on 16mm. There’s a beautiful idea that a century has a medium tied to it, but then there’s obsolescence in film as we’re in 21st century.

Film, of course, does have a role in the 21st century. If you’re talking about archival concerns, digital is not a proven thing. The idea that I can have a negative on modern polyester stock, put it in a can in a climate-controlled vault with minimal fluctuations in humidity and temperature, and I can reasonably expect that if I take this film out of a can in ten or twenty years, it’s going to be stable. But for anyone who has tried to recover information from an old hard drive or an old floppy disk, the very idea of archiving things digitally–even though it is inherently unstable and its features are often dictated by consumer demand rather than long-term storage concerns–is a troubling thing. There’s a place for film because we understand what it is and what it does well. There may be a time when digital is better, but at the moment you’re always looking at migration, compatibility and proprietary file formats–things that are obstacles to long-term access in a way that should not be taken lightly.

Kirill: So you’re talking about all aspects of film, shooting, projecting, and archiving?

Kyle: It’s a complicated question. There are certain reasons why a cinematographer would want to shoot digital, and I don’t begrudge them needing and liking those tools. I don’t take a line in the sand that I won’t see a film shot digitally, but I’ll be honest and say that they don’t move me as much. We sponsored a Home Movie Day last week, where people bring old super-8 or 16mm old movies that they shot, which is not the same as Hi-8 or VHS tapes. There’s a different quality to the image, a different physicality to the image being on film. I will admit that this has an emotional pull on me that video does not, or does not yet.

At the same time, who am I to say that people shouldn’t shoot on digital? Who am I to say that post-production technicians shouldn’t avail themselves of digital workflows or digital intermediates that are simply facts in the industry? In that sense, projectionists can’t stand in front of the tide of progress. But if you talk to cinematographers, most of them will also say that they want to have film as an option for a particular ‘film look’ that’s valuable, a look that is more valuable than what market forces might appear to make it.

In terms of projection, I am more staunchly in favor of film projection simply because digital projection is not very well understood. We’ve been going through a very chaotic transition over the few past years, especially since “Avatar.”

The studios have been pushing exhibitors to convert to digital projection, and there’s a level at which this is good, the level where previously digital projection had no standards. If you were running a film festival or a cinematheque, and you were dealing with independent filmmakers, this was a real problem. This has been a long saga and someone has always been on the short end. There was decades-long period of time where if you wanted your film to be seen and distributed, you had to make a 35mm print. You might have shot on 16mm, you might have shot on super-8 or on video, and the expense of going to a 35mm duplicate negative or internegative, and making a release print was a substantial barrier.

But the tide turning in the last decade placed the responsibility on exhibitors to meet the need of filmmakers. If you’re running a film festival, especially a regional one that is not industry-affiliated, truly dealing one-on-one with independent film makers, you’ll get requests to show it on DVD, on Blu-ray, on DVCAM, on BetaSP, on DigiBeta, on HDCam, from a hard drive, from a MacBook–I’ve dealt with all of these. And to some extent it was very chaotic and unsustainable: film was too expensive for filmmakers, but getting all the technical capabilities was too expensive for all but the wealthiest venues. There was this unproductive standstill.

There’s an extent to which DCP (Digital Cinema Package), which is what all the studios have signed on to and pushed, is good. You’re not dealing with different people who’re saying, “I have a tape,” “I have a disc,” “I have something I’ve burned on my computer, take it, it won’t skip” and that’s good. The problem is in how it was implemented as a closed system, and in a way that has not been talked about enough. If you ask the person on the street “What are you seeing when you go to a movie theater?,” most of them assume it’s already digital. Most would genuinely think that you go into the projection booth and you put a DVD on screen, using the same kind of consumer products that they are familiar with.

The fact of the matter is that film is great because it’s a very open standard. If your film is manufactured with non-standard perforation, you’re out of luck, but 35mm has been an international standard going back decades. I can send a print to China, someone in Argentina can send a print to me, it can go to Africa, to Europe, to all corners of the United States, and it’s standard. I can put it in a projector, and while there might be some quirks in the lab processing and there might be some sound system that is more prevalent in one country than another, by and large if you give me a 35mm print in good condition, I can project it. I can project it as many times as I want, and I can project it whenever I want. I can go into the projection booth at 4 am, and if it’s my inclination to thread up a print and watch it just for myself, I can.

This is not the case with digital. It’s not our technology, it’s something very closed. It doesn’t necessarily have to be, as you can make and distribute DCP in an unencrypted way that doesn’t need keys. Right now the studios send you a hard drive and it uploads to a local server in your multiplex theater, where you have a repository of files from different hard drives, and eventually they get wiped off and you send back the hard drive. The idea is later to do all this via a satellite network, eliminating the physical intermediary of a hard drive. And to play these files you need keys from the studio or distributor. A key can be as simple as accessing the file, or as extreme as telling you how many times you can show the file and when you can show it. It can say that your projector is going to shut down after a certain time code, it’s a kind of digital rights management (DRM) on steroids.

From the archival perspective this is not very good. We can acquire a print. We can put that print in a can on a shelf, we can pull it out ten years later and it was more or less the same way as we left it and we can thread it up. We can catalogue it and do all the things to maintain the collection. If you send me a hard drive and I put it on a shelf, but I don’t have the key to open it, or the key that I have only allows access until December 31, 2012, then it’s a bunch of chips after that and it doesn’t mean anything.

There have been horror stories at film festivals recently of server errors, files not being played back properly, files not being able to be accessed even though the studio gave you a key – well, there might be a problem with the key, or a server problem on their end. And all of a sudden instead of being able to take the film and have a very physical relationship with it, being able to wind through it and evaluate what’s wrong with it and what needs to be done to make it go through a projector safely, now you have to call up the IT division of the studio. And maybe you’re doing the screening on the weekend and there’s no one at the IT division, or you’re one out of two-hundred calls, or they’ve outsourced to a third-party company that doesn’t understand your relationship with this distributor and how important it is that you really need to get this key to open the file for your very important festival screening.

There’s a significant way in which transitioning to digital in terms of exhibition is a substantial reduction of freedom for the exhibitor as a whole, not just the projectionist.

Another view of the Eastman 25 16mm projector.

Kirill: Does this also marginalize the craft of operating a film projector?

Kyle: There is a level of craft that is invisible and not appreciated. The old adage says that you never know about the projectionist until something goes wrong, you’re not conscious that there’s someone in the booth and that there’s labor going on, unless the film breaks. In the archival field, we say that film is human-eye readable. Let’s say in 200 years from now there’s no one alive who’s ever threaded up a projector. They can still open up a can and wind through a reel of film, and they can see that there’s data there. What if you dust off a hard drive 200 years from now and there’s some proprietary format–what can you do with that?

In a way, the problems aren’t localized. I’m winding through the film and I see a bad splice that needs to be corrected, or an area with a scratch, or a point with some adhesive on the film. When I’m projecting that film that I’ve wound through, I can look at the screen and see the manifestation of that thing that I noted earlier. A server error or a data blip doesn’t have that relationship. You can listen to a vinyl record, and you look at it and see a scratch, and later hear the artifact of that during the playback. This is not to say that all films and records should be scratched, or should have some mark that says that a human being touched it – it’s great to see a film in perfect condition.

But there’s a way to understand what is in front of us. I have a bad print, but it’s the only print in the United States of a title, and I’ve got it from a private collector, or our archive happens to have the only copy. It’s not the best copy, it’s faded, it’s splicey, but it’s all that there is. I can go up in front of the audience and say that there’s this physical artifact with extraordinary material history, and you’re going to see the reflection of that on the screen, some fading, points where the image jumps – because it was used. And the fact of the matter is that a digital file doesn’t have that kind of trail, and the problems that arise with digital are not human problems. They are human problems on the level that we need to build a better server and a better IT network. But on the level of, How did a person handle this, How did they treat it and to what extent is what we see now an accumulation of everyone that ever touched it, that is not the case.

Kirill: As more films are done completely in digital, and studios release the back catalogues in Blu-ray format, do you see archives transitioning to purely digital format in the future?

Kyle: It’s an interesting question, because even though movies are done digitally, studios are still doing film for protection. They’re still doing separation masters of a color film. Color negative, although it’s better than it used to be, still has fading characteristics that black-and-white negatives don’t have. And to protect these color assets–which is what they are to the studios–they do separations along the color spectrum. And that is still being done on film, as there is understanding that at some point there might be a robust, migration-proof, hard drive crash-proof way of archiving digitally, but for the moment film is not proprietary. Film does not require you to renew your license.

I don’t want to come off as saying that digital is all bad. There are so many ways in which digital is important, let’s be honest. If I want the work of this archive, or any archive, to be shared, if the studio wants its work to be disseminated, being able to show it as a 35mm print is very specialized thing now. If we’re spending all of this money to make a print, and it goes out, we don’t want to send it to a multiplex where it’s going to be all spliced together and put on a platter system and projected without there being anyone overseeing the machine. There’s a relative handful of venues that have the ability and that care enough to treat prints well.

If we don’t make films available digitally, the broad majority of people won’t be able to see them. They won’t be able to go to a brick-and-mortar store or an online store and purchase a DVD or Blu-ray version. Let’s face it–there are a lot of people who don’t live in a town that has a cinematheque, that don’t live in a place where someone finds out about a new print struck by the Library of Congress or the George Eastman House and says “I must show it.” If the only way a person can see something is through a digital copy, I don’t say that this person has to be a purist and see it on film. And at the same time, there’s a level on which the DVD and Blu-ray market opened up studio catalogues, spurring a great deal of preservation. There’s been more preservation in the last decade than in any decade before it. It happened because these assets became exploitable again, because we got into higher resolution formats.

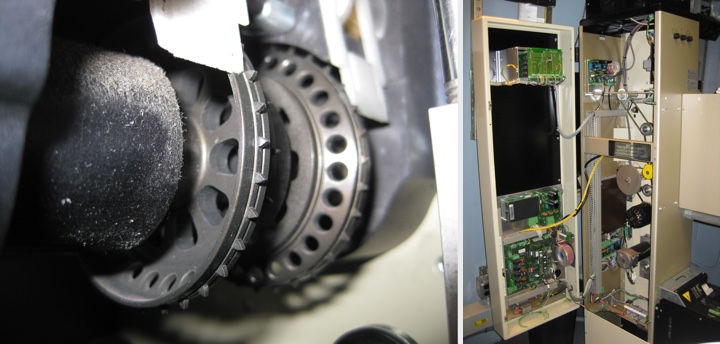

Intermittent sprocket on the Century C 35mm projector.

Kirill: Are you talking about taking existing material and providing it in digital format, or going all the way back to restore material that was not publicly available before?

Kyle: You might have a film without a surviving original camera negative. You might have a mediocre dupe negative. Or perhaps two dupe negatives where one is missing a scene, and you have to go to print to get a scene or talk to another archive to get material and recombine it. Or you might have a nitrate negative that is starting to decompose and you have to transfer that information to another film stock as polyester protection material so it will endure.

And in all cases the gold standard is film, the gold standard where you’re not losing data, where you’re not working with proprietary formats. It was the case that in 1980s as VHS was coming into its own that the studio could take any print that they had off the shelf, do a quick and dirty transfer, and put it on VHS. There was a clamoring for content on VHS, and the quality of the material you selected for transfer did not matter–a print, a negative or something else. And for the most part there wasn’t any critical thought towards, What is the ideal element, What is the best surviving material on this film.

As consumer formats matured, and you had more high-resolution format such as DVD and Blu-ray, just taking any old transfer off the shelf wasn’t standard operating procedure anymore. In many cases, ironically, the only way to get digital assets and put them on a disc in a box that you can buy at Target, Best Buy or Amazon–to do it efficiently and correctly, to yield the best image that is sufficient for those formats–is to go back to the film elements, to go back and do the full photo-chemical restoration job, to go back and set right the mistakes of the past.

Kirill: Because it has the full level of details?

Kyle: Exactly. Because by definition you cannot improve upon the camera negative. That’s literally the emulsion that was exposed when the film went through the camera gate. You can’t get anything better than that, and it’s often the case that preservation material from forty years ago– stuff that was film-to-film transfer, the only way to do preservation back then–might have used a lab with different set of lenses, or a less sophisticated printer. There are modern techniques that can yield better preservation material. So even though you may already have a preservation negative, it makes sense to go back to the earliest, most original element.

It makes sense to go back and say “Can we do a better job, can we make a better transfer” with the view that we’re going to have, on the one hand, better protection material on film, and on the other hand, a better-looking digital asset for consumption by a mass audience.

Kirill: Is the growing back catalogue a by-product of the ongoing restoration process?

Kyle: One is not really the by-product of another. They’re working together. The studios could not do film preservation to the extent they have if there wasn’t a bottom line reason to do it. They’re for-profit corporations, and ultimately if it makes sense to return to the camera negative of “The Wizard of Oz” because you have to put out a Blu-ray of it, and the existing transfer is good but you can improve it with modern technology, then you do that and you also create a film backup. But at the same time these things are incredibly intertwined.

You need the consumer formats to be able to fund these preservation efforts, but you also cannot have your lucrative consumer formats unless you’re really taking care of your assets and unless you’re doing the right thing by them, unless you’re constantly revisiting them and asking “Can we improve this?”

And luckily, it’s not as if the only things being restored are the things that you see on DVD. DVD has reached a point where it’s matured, where the back catalogue releases are not quite as steady as they once were because we’re dealing with films that are in many cases not A-list catalogue titles. I think a lot of them are better in terms of what they mean to me as a film goer, in terms of what I cherish about film history. There are still plenty of films–thousands of films–that are not available on DVD and Blu-ray, but in terms of the titles that are available and are revisited, that are the evergreens for the studios, where they can release a copy of “The Ten Commandments” or “Gone With the Wind” or “The Searchers” or “Star Wars” over and over again.

That is also able to fund more marginal titles, to fund the things that studio recognizes that they have an obligation to preserve. They’ve made this. As a cultural entity, and as a corporate entity, this is an asset that can wait in the vault for future exploitation. If they spend $20K now, they can exploit it for another 100 years even if they decide not to exploit it tomorrow.

On left – intermittent sprocket on the Kinoton FP38E 35mm/16mm projector. On right – the electronically-regulated interior of the Kinoton FP38E 35mm/16mm projector.

Kirill: Does this long tail feed back into repertory theaters where people expect to discover and rediscover movies?

Kyle: Yes, and a lot of repertory programming is possible because of restoration efforts and these efforts are part of this long tail. At the same time, I will say that repertory tends to be the poor stepchild, not through the fault of anyone really, but simply because if you’re taking about doing a high quality scan of an original negative in 2K, 4K, 6K or 8K, you want to return to the most original element, to the original camera negative if possible, or the closest thing and to make a new preservation negative. Video transfers are done from camera negatives or interpositives, not prints.

In terms of actually making a print, a print has a very limited life. A studio can restore a title, or an archive can restore a title, and the ultimate goal is a new polyester protection negative. The new negative becomes the element used for all future needs, including scanning and transfer. If you’re following best practices, you make a print from your negative. That’s the best way to check your negative–see if it needs further correction, whether a decent print can be made from it at all. But actually making that print–what’s it worth? Its only real use is as an exhibition medium and there are only a handful of venues interested in exhibiting it. You’ve done your due diligence, you’ve made preservation material and a digital asset that can be used for future exploitation, and you’re going over budget at your studio and you’re saying, “Do we want to spend thousands of dollars to make a print that five people are going to show, that’s going to sit in the vault and never going to be seen?” In some ways, prints are the most neglected part.

You’re making a new print, and that’s great, but the only way you’re going to earn your investment back is by showing it or by renting it out over and over again. Frankly, you will most likely have a print that’s ruined and damaged before you can make your investment back. You’re not talking about a wide release, but something that’s going to art houses, something that’s not playing continuously but is just a one night stand at a venue in Chicago or St Louis. It passes through 40 different projection booths by the time you make your money back. You very well might not make your money back as it could be damaged the third time someone shows it.

Fortunately from the archival point of view, we’re not so bottomline-oriented. Politically, as an institution, we feel there’s a value in making these new prints. We’re not saying, “We’re not going to make a print or preservation because we expect that only five people will want to borrow the print”. We have a different mandate and different goals, and our funding stream is different, and so we’re lucky enough to do that.

Kirill: Do you see the studios experimenting in exposing the long tail of the content through Internet streaming services such as Netflix or Amazon, hoping to return their investment in 10-15 years?

Kyle: Certainly the studios are very interested in streaming and VOD (Video on Demand) right now, and certainly other institutions like archives are interested in streaming content that can be made available through these new platforms. Theatrical revenue is declining, home video is declining and there has to be a new way to make this equation work. There are things that unceremoniously went up on Netflix instant viewing that have never been available on home video, that are very difficult to obtain as a 35mm or 16mm print.

But the fact of the matter is that streaming has its limitations. Because of the bandwidth that most people are using, because of the quality of connection that most people have, streaming is right now at a point where the quality of your source is not so paramount, and whereas a studio will have to go back to the camera negative or the earliest surviving material to master a decent Blu-ray, it’s not at all uncommon to pull off the transfer from the shelf done twenty or thirty years ago to meet the streaming demands. Most likely the compression and the rest of artifacting that’s inherent in streaming right now due to the current IT network make it not so important. If the studio can just pull out a tape that was mastered twenty years ago, that isn’t especially helping preservation. It’s good for cinephiles who are rabid to see this film and don’t care about the quality, and in a way don’t care if what they’re doing is sustainable…

If the studio is getting revenue from streaming, that’s great, but that doesn’t send the same message as all the people coming in to see a print, deciding to take time out of their day to pay admission and to come into a theater, and this theater is telling us that they want to bring the print back and show it again. It doesn’t have the same ripple effect of positive action and encouragement right now, but it doesn’t mean that it won’t ever have that effect as streaming becomes more sophisticated.

As bandwidth becomes less of an issue and high-speed Internet becomes standardized in a way that it’s not now, and the standards for streaming go up, maybe it will be the case where people will say, “This copy is unacceptable,” and people will have to go back and do preservation and restoration so that they have a decent copy to stream. So long as the material is looked after in a way that allows the people who own it understand that there is value in it, that there is demand for it, that it is sensible to work on it, preserve it and conserve it, ultimately that’s good. I would prefer, of course, for it to be seen on film because that’s how it was seen, and if you’re watching the film on your laptop, it could be an HD copy of it, but it’s still your laptop, it’s still not the same as being somewhere and having this physical thing going in front of beam of light. It’s just fundamentally, aesthetically, materially different.

Kirill: My impression is that the rise of VHS in the 1980s marked the end of the movie theaters “owning” the experience of watching movies. The advent of DVD and Blu-ray is now combined with the push from TV manufacturers that try to lure the consumer back into his living room with widescreen, high definition and 3D experiences. Do you see the movie creators, exhibitiors, and projectionists “fighting back” to get the movie goers back into the theaters?

Kyle: There’s not one argument, there’s not one silver bullet – there are people who say, “Yes, i like seeing a film with an audience but at the same time i don’t like seeing it when the audience spilled their cola all over the floor and there’s a screaming child, and it’s a better experience when I’m watching it at home on my HDTV through my Blu-ray”.

Earlier I brought up the issue of vinyl and how that’s had something of a resurgence. The same thing is possible with film. I think there is a hunger, especially among my generation, for this physical media. It might not be all that apparent until it’s almost gone, which is to say that we might not appreciate it until everything is essentially just a file in the cloud. But as you can see, we’re living in the age of iTunes and concurrently there are people who are now fanatical about vinyl. If you told me ten years ago that there’s going to be a new record store, and it’s going to open up and it will mostly sell vinyl, and people will pay more for vinyl than they ever did for a CD, and there’ll be this real aficionado appreciation of “I’m getting something and it’s not just a file on my iPod, or a file in my cloud or a file in my Ultraviolet locker, but I have this thing in front of me.” I think that that appetite can certainly be there with film, but I also think that at the same time it’s not a one-pronged thing.

The audience thing is important, and I think that there is a longing for community that shouldn’t be discounted. Programmers and theater managers and projectionists who are, most probably, the most staunchly pro-film people in the country just by the basis of their job, have to interface with video every day. They have to preview films on a DVD copy, decide whether to show it. I’m not opposed to the home media–it’s convenient, it represents certain advantages over seeing something communally. But at the same time I think there is the sense that people do want to go see something, that they do want to experience it with other people in a communal space.

And there is something romantic about movies not just as celluloid and not just as an experience, but as a totality. This is to say that if the revenue was really in streaming, or the revenue was really in home video, and the studios were able to totally cut out the theatrical and just say that everything is going to go direct-to-video because we can control this more, or this is just a more profitable way of doing it, then this would happen. We’ve had home video for decades now, and how prestigious are direct-to-video releases? There’s still a media consciousness about something “opening in theaters next week,” and there’s a level at which it’s news, and it’s reviewed online and in newspapers and on television, and there’s a new movie opening and this is a cultural event in a way that is very difficult to imagine when you say, “We have assembled this great cast, and we have this great director and starting tomorrow you can stream it.” It’s not a cultural thing in the same way, and that’s important.

A modern reverse scan Dolby Digital sound head on the Kinoton FP38E 35mm/16mm projector.

Kirill: What are your thoughts on the avalanche of 3D productions that came after the enormous box office success of “Avatar”?

Kyle: As someone who is happy to spend a day watching silent black-and-white films that are definitely 2D and lack a lot of other things if you’re just going by that kind of metric, I don’t want to say that cinema was missing something before 3D. There’s an extraordinary film made by Peter Kubelka called “Arnulf Rainer” that is the purest film you can imagine. The only components of it are black frames and white frames, and the only sound is either the black of no sound or the white noise of the soundtrack, and the film is about the infinite variations of these, and how it can create rhythm and how it can be moving. And that’s an extraordinary film, and there are plenty of extraordinary films that are black-and-white, there are plenty of extraordinary films in color, there are plenty of ones that don’t have sound, and it’s a different kind of medium.

At the same time I’m reluctant to say that 3D adds nothing. Have I ever seen 3D that made me think, “My God, I can never go back to watching a 2D film” or “This experience is essential in 3D”? I haven’t, but that’s not to say that it won’t come along. But new technology doesn’t make old experiences obsolete or emotionally invalid.

In terms of the 3D craze, one thing that does need to be understood is the extent to which 3D is the major justification to the conversion to digital projection. From an exhibitor’s point of view, what are the advantages that you gain with digital? You don’t have to deal with prints, you don’t have to pay a projectionist – but frankly they make up such a minor portion of a theater’s balance sheet, that these savings in no way exceed the cost of going digital.

Kirill: I’ve heard the figure of one million dollars that the studios are saving on average by doing digital projection.

Kyle: This is what I’m getting at. It makes sense for the studios. If suddenly you don’t have to make 3,000 prints of something and just duplicate a hard drive – and eventually beam it from a huge server via satellite – this is a significant savings for the studios. But is there something in digital projection that makes sense for an exhibitor to spend $60-100K per screen? Is the audience going to increase that much, and is the expense going to be counterbalanced? The answer is frankly no, that a lot of people don’t really care whether your film is projected on film or digitally.

But then you start saying that this is only available in digital 3D. And look at all the money “Avatar” made in digital 3D. Just think: when you have the next “Avatar,” do you want to be the theater that converted to digital and has a full house, or do you want to be the one showing it in 2D on 35mm to an empty house? So in a lot of ways 3D has that function of legitimizing digital and also making it necessary for exhibitors.

Of course, who knows whether there will be another “Avatar,” who knows whether the next huge blockbuster will be 3D? The studios obviously would like it to be. The equipment manufacturers would like it to be in 3D. But is audience interest in 3D sustainable? I’m sure we both read figures about how the share of screens that make up the film gross in 3D is declining, which is to say people are still going to see the film, but are opting to spend less money and not wear the glasses. That’s a scenario that’s very bad for the 3D equipment manufacturers and the studios.

Kirill: Doesn’t that go against your point that exhibitors are not going to maintain multiple variants of the projection equipment?

Kyle: Let’s talk about this from a few points of view. Logistically speaking, the very worst scenario if you have to make prints is to have 1,500 play dates that are prints and 1,500 play dates that are digital. If all 3,000 were film or all 3,000 were digital, you can have an economy of scale. You still have an economy of scale at the level of the major production, but on the distribution side you have to keep two production lines up and running that aren’t really compatible.

And that’s not a good solution, if the equilibrium is 50% prints and 50% digital, then you have a system that is not efficient at all, and which is probably more expensive than what was there in the first place with 35mm. And to assure that there is full or reasonably full conversion, the studios have instituted the Virtual Print Fee where the studios grant you a credit that helps you upgrade and there’s a discount on future bookings. And often there’s a stipulation tied up that you discard your film equipment, that your 35mm projector that might have been in your theater for thirty or forty years is disassembled, is thrown in the dumpster and made inoperable.

So when your digital projector breaks, you can’t go back and say that it would be better from your point of view to just go back to film. Five years down the line no one wants to be dealing with film, no one wants the possibility that people will be able to say, “You know what, this is something that we shouldn’t have discarded”. There has to be a complete ideological and mechanical transformation for the conversion to make sense.

Kirill: How far along is the digital conversion across the large exhibitors, and how reliable has the new equipment proven out to be so far?

Kyle: The digital transition has sped up in the last two years largely because there was a period when standards were not in place, when equipment was not reliable and largely because financing was not worked out. The last decade was filled with proclamations that film will be dead next year, all theaters will be digital next year – I remember this going back to 2001 or so. And it never quite happened that quickly, because the exhibitors looked at it and said, “If we’re going to spend $100,000 per screen, what are we getting out of it, and is there any conceivable reason why we should do this, and where is our cashflow going to come from?”

It has been a long time coming, it’s been slow and the momentum is building. The conversion figures are changing every week, and I would say that right now it’s approximately 50%, and you’re never going to get a 100% compliance. There are some regional chains, some independent houses, some art houses that are simply not capitalized sufficiently to be able to convert. If the customer base for a print is so small, your costs are going to go up and it essentially becomes a niche, not cost-efficient product.

And there will be a day–no one knows when–when as a distributor you stand on a financially better footing by writing off exhibitors who aren’t able to afford to convert. Most likely if they can’t afford to convert to digital, they don’t have very many admissions, they’re in a very low population area, and ultimately your returns for “Fast Five” or “Captain America” don’t hinge on a theater in South Dakota shutting down or not–they’re a rounding error, more or less. And so necessarily there will be a point before 100% conversion where it’s simply decided that these film exhibitors are a drag on the economy of film distribution–and that will be a day of transition, to put it euphemistically.

In terms of the reliability of digital equipment, the problem from my point of view is that we’re really operating in uncharted waters. Up in the Dryden booth where I work, we have projectors that were built in 1937. They’ve been installed and running continuously since 1951, they’re Century Model Cs. There’s a level at which, for most of the cinema’s life, projection equipment was heavy industrial stuff with a very long lifespan, relatively simple maintenance regimes and a wide availability of spare parts. These machines kept on going and could be used for decades. A theater would close and its assets would be resold to another theater or another chain, refurbished, retrofitted, reused–for years and years and years.

And quite simply, digital technology has not proven to have that kind of longevity. How many laptops have you had in the last decade? How many times have you gotten a new drive? How many ways have you stored your files? And there’s a sense in which this equilibrium cannot exist because the economics of technology as we experience them now are about upgrading, getting more memory, getting a more robust operating system, over and over again. This is by design. You use your laptop for 3 years and then you’re embarrassed to even have it, you have to upgrade.

Kirill: Are you talking about home machines or the projection equipment at big houses?

Kyle: I’m saying that the whole paradigm has shifted, a convergence. Industry is using consumer equipment with minimal modification. If you take out home use of computer electronics and you just look at business use, your time span is a bit longer, but businesses are always upgrading their networks, they’re always getting new machines, they always have to get something else to be able to run new software and to be able to take advantage of it. And the idea that someone can make a digital projector that will still be working in 60 years, that will have a stable platform, stable file format, stable compatibility, and that we’re not going to say that we will find a new codec, a new way to compress the data more efficiently, a better colorspace…

Technology is going to go there, and quite simply 35mm was lucky to have all of the developments on the level of emulsions, film stocks, laboratory practice and auxiliary equipment. But ultimately you send a print to a theater, and I can take a nitrate print from 100 years ago, and assuming it’s in good shape, I can put it on our projector. I can take an acetate print from 50 years ago, and if it’s in good shape and I’ve repaired it, I can put it on the projector. I can take a modern print and put it on the projector. I can avail myself of these technological advancements using equipment that needs very few upgrades and a very limited maintenance regime. It is heavily backwards-compatible.

Our experience with computers and modern consumer electronics, whether we’re using them at home or business simply contradicts this idea that we can have this kind of industrial strength technology that lasts without a constant stream of upgrades.

Kirill: So effectively your doomsday scenario from the archival perspective is not being able to take a digital file in 50 years from now and be able to find a projection system to play it.

Kyle: Not even a projection system. If want to edit it, if you want to find a way to stream it through whatever system you’ve set up in 50 years from now–how are you going to be able to read that file, and do you know that you can read that file? Has the hard drive been corrupted, how many backup copies do you have, are you migrating the data? When a whole company’s identity and profit system is based on the idea that we’re developing a file format, and it’s going to work with our tapes or the software we have, and we’re going to have a proprietary format – what if that company goes under? What if you upgrade to a different operating system that is not compatible?

There’s an extent to which archivally we really cannot know whether these zeroes and ones are going to be read in the same way. We can take precautions, we can use open source, we can steer away from proprietary formats, we can try to be stable in what we do. But if you talk to people in post-production, you’re talking about bits and pieces taken from various software systems where you might edit sound using this program, we might do color correction using that program–and we might have digital data in all of these ways that are disparate and might not be compatible, or might make sense with the machine we have right now. But if we try to plug it in later, or try to take stuff off the hard drive, we might not be able to do this, and probably won’t be able to do this.

The real test of this is people thinking about their own relation to technology over the last decade. Can you look at those things that you’ve saved on a floppy disk or a zip disk? Can you look at those things that you’ve typed in Microsoft Works? Can you access these files, can you access your hard drive from three hard drives ago? And if the answer is no, that should give us pause.

Kirill: It’s interesting that you’re talking beyond the fleeting moment of the latest movie releases, and are thinking about how we’re going to watch “Avatar” a 100 years from now.

Kyle: If the most sensible way, economically, is to screen “Avatar” digitally, and if it really, truly makes sense for exhibitor, distributor, and the producer, if that’s where the industry is going, I’m not going to picket at AMC and say, “You must show film, you must not show digital.” Digital technology has a place today because that’s what people are interested in, that’s what the producers are excited about. The idea that you can do digital 3D stimulates James Cameron, stimulates a lot of film goers and stimulates a lot of studio executives.

I don’t object to that. But if we’re talking about the posterity of this, if we’re talking about being guardians of this culture and keeping it, we need to think longer term and we need to think, Will this great (or mediocre) technology today be a workable technology tomorrow? And we also have to be honest with ourselves to say that we don’t know all the time.

So in many ways the most sensible thing for digital media is to keep digital backup, to keep your data as data, but also have some kind of physical backup, to have it on film, to have it on tape, to have it on these proven analog mediums that we understand and that are relatively stable from the point of the view of access.

On left – the heavily mechanical (and greasy!) interior of a Century C 35mm projector. On right – flammable nitrate films can be projected on the Century C 35mm projector with proper enclosures.

And here I’d like to thank Rebecca Hall at Northwest Chicago Film Society for helping me get in touch with Kyle, and of course Kyle Westphal for the incredibly detailed look at the effects of digital conversion on cinema exhibition and projection. Kyle’s headshot is courtesy of R.F. Hall, and all the rest of the images were graciously provided by Kyle.

“Midnight in Paris” is the latest production written and directed by Woody Allen. A young couple, portrayed by Owen Wilson and Rachel McAdams, travels to Paris on the eve of their wedding. As Owen’s character falls in love with the city, the movie takes an unexpected turn, exploring a nostalgic – and at times over-idealized – fantasy that a life different from ours would be much better. The opening sequence of the movie, with the camera lingering lazily on stunning Parisian vistas, sets the visual tone for the entire movie, with fantastic performances from a star-studded cast.

Anne Seibel is responsible for the flawlessly executed production design of the movie. Over the last couple of decades she has worked on numerous productions, from “Marie Antoinette” to “Munich”, from “Swordfish” to “The Happening”. I am quite delighted that Anne has agreed to answer a few questions I had about her work on the movie and her craft in general.

Kirill: Can you tell us a little bit about yourself and your background?

Kirill: Can you tell us a little bit about yourself and your background?

Anne: I studied in an architecture school, and I always liked doing art props for dance shows and family productions. My family was not in the movie business, but rather in science and medicine, and I went to study architecture. One day a friend of my parents offered to take me to a movie set, and I was very curious to see what happens during the shoot. There I realized there was an entire team of people doing what I was doing at home – making the sets – and it attracted me. I realized that with my background in architecture I can be part of such a team.

After finishing the school I had a chance encounter with someone working in the movie business, and when he asked me what I wanted to do, I told him that I wanted to do sets for movies. He offered me a job to draw a few sets for the fund-raising presentation. After working there and meeting a few people I have decided to call ten best designers in France to get an assistant position.

And then one day, I met a big designer named Serge Douy at the bar and he told me that he has a small job to mirror an english crew coming to Paris to film a movie, and he needs someone who speaks english. I asked which movie was that, and he said that it’s a James Bond movie – and I screamed inside my head.

Kirill: And that was “A View to a Kill” in 1985?

Anne: Exactly. That was my opportunity to start working on english-speaking american productions. I made friends with set decorator Jille Azis whom I was mirroring, and I went with her to her next movie, “The Living Daylights” which was shot in Morocco with a french speaking crew. From there I continued working first as an assistant art director, and later as an art director, on additional productions that came to France. I also did french movies as additional education with great designers, most of whom are now gone. And as time went, I learned my skill from great production designers that I worked with.

Kirill: What are your impressions working on american movies shot in Europe?

Anne: Sometimes I am hired as an art director to recreate the Paris parts of the movie outside France itself, in Budapest or Prague, for example. This happened on “G.I. Joe” with Ed Verreaux and “Munich” with Rick Carter. On other movies, such as “Rush Hour” or other scenes in “Munich” I work in France. Even “Marie Antoinette” is an american movie, even though it is about french history. I worked with K.K. Barrett as a supervising art director, and it goes very deep into the local history and culture, which might be difficult for an American to understand in detail – same as it would be difficult for me to research and recreate New York or London, more difficult because it’s not in my blood.

We were doing “Munich” with the production designer Rick Carter in Paris, and for financial reasons some parts were shot later in Budapest. At first I thought that I would not be doing those parts, but he called me and asked me to join him in Budapest to continue the work, and it was fantastic.

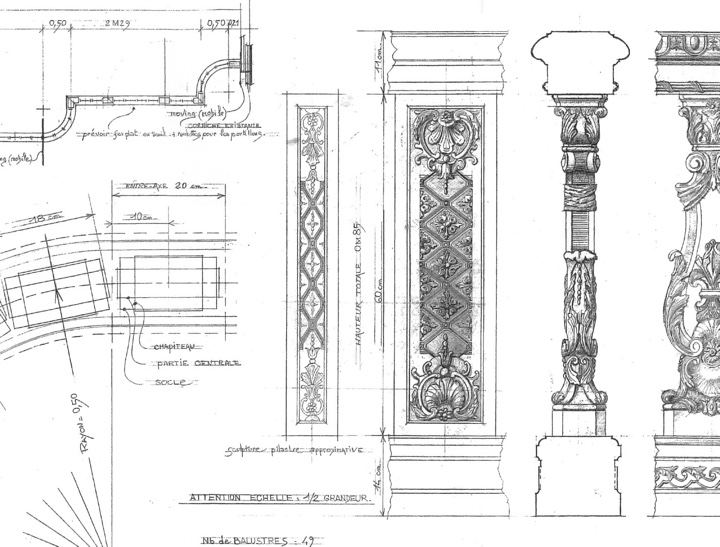

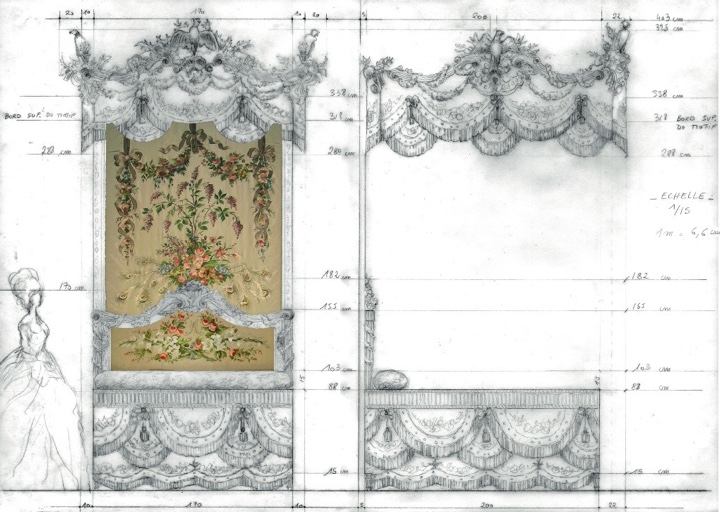

Marie Antoinette, detailed bedroom plan. Click to see fullsize image.

Marie Antoinette, detailed bedroom drawing.

Marie Antoinette, bedroom location before decoration.

Marie Antoinette, bedroom location after decoration.

Marie Antoinette, final stills.

Kirill: I was just recently watching “Marie Antoinette” again, and it is so unbelievably rich in color, texture and incredibly lush set decorations. How did it go on your side?

Anne: It’s one of my best memories. It was such a nice and warm vibe working with Sofia Coppola. I did a lot of research, and had a real thrill doing all the construction. It was such a pleasure to go into the smallest details reproducing Versailles, to see how it was done – a really good way of learning history, better than at school. It was fantastic to go to Versailles, to meet the people who maintain the gardens and to talk with historians. I met this completely mad woman who is collecting everything about Marie Antoinette, and it was really incredible to see some of the pieces. It’s a really interesting part of our job to do the research, to put yourself in a different period.

We also spent a lot of time on small details. For example, we made extensive camera tests to find the right color of the gold. We didn’t want it to be too pink or too green, and you might not have noticed it, but it does not feel cold. We looked very carefully at colors and fabrics, and how they reproduced on the screen.

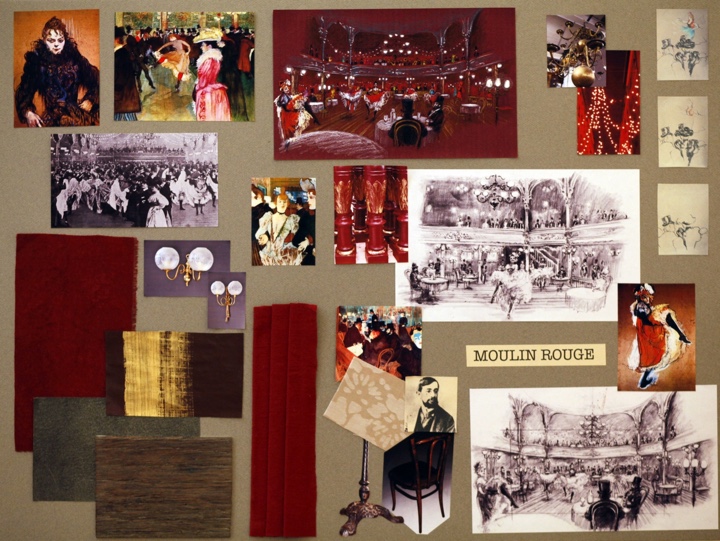

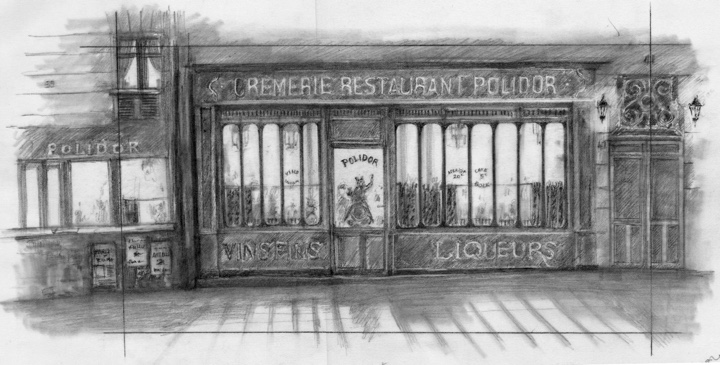

Kirill: This brings me to your latest movie, “Midnight In Paris”. It also has a very stylish look from the very first opening sequence. As the production designer of this movie, what was the initial exploration stage between you, the cinematographer and the director?

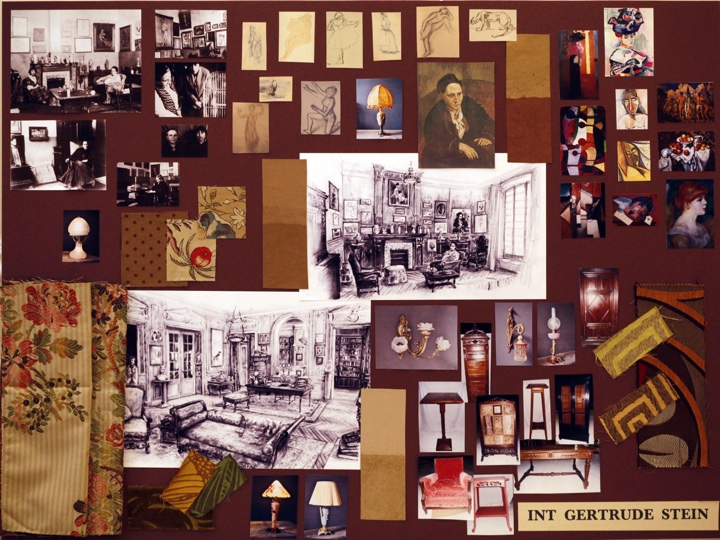

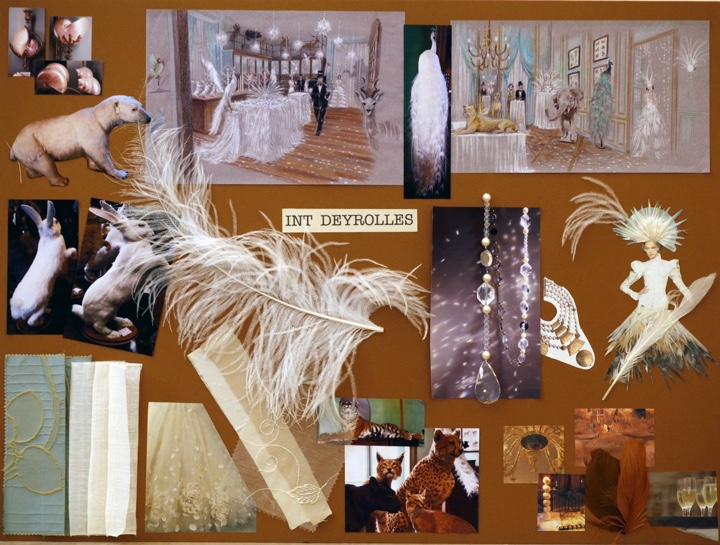

Anne: Woody Allen movies are different. The very first thing they told me during the interview – no construction, as Woody does not spend more the 10 million dollars per movie. With such a small budget for art department it was a challenge to do this movie in France. As soon as casting was over and I started working on it, I spent a lot of time researching the period. It was about two months before the shooting started, watching films, reading books and other materials.

I had very little discussion with Woody Allen. I saw him for an hour in New York, and about half an hour in Cannes after I’ve already looked at different locations that I could transform and adjust for the different periods of the movie. The contemporary period was the simplest, even when we tried to achieve a certain look with the cinematographer Darius Khondji. When I first met Darius, I gave him all my research to get on the same level. We worked closely, particularly on the colors and light of the period – brown, maroon and beige – and brighter colors for contemporary, to give a sense of passing from one period to another. And we had these great conversations about colors that I wanted to use, and how it fit into the look that he was targetting. We also talked a lot about the lighting and the practicals that we equiped in a certain way to affect the mood. I had another DoP (director of photography) calling me and asking how we managed to achieve this unity of lighting – and it’s because we worked together from the beginning on colors, texture of the shade, vibration of the bulbs and dim of the lights.