In the past year or so I’ve been working on a new project. Aurora is a set of libraries for building Compose Desktop apps, taking most of the building blocks from Radiance. I don’t have a firm date yet for when the first release of Aurora will be available, but in the meanwhile I want to talk about something I’ve been playing with over the last few weeks.

Skia is a library that serves as the graphics engine for Chrome, Android, Flutter, Firefox and many other popular platforms. It has also been chosen by Jetbrains as the graphics engine for Compose Desktop. One of the more interesting parts of Skia is SkSL – Skia’s shading language – that allows writing fast and powerful fragment shaders. While shaders are usually associated with rendering complex scenes in video games and CGI effects, in this post I’m going to show how I’m using Skia shaders to render textured backgrounds for desktop apps.

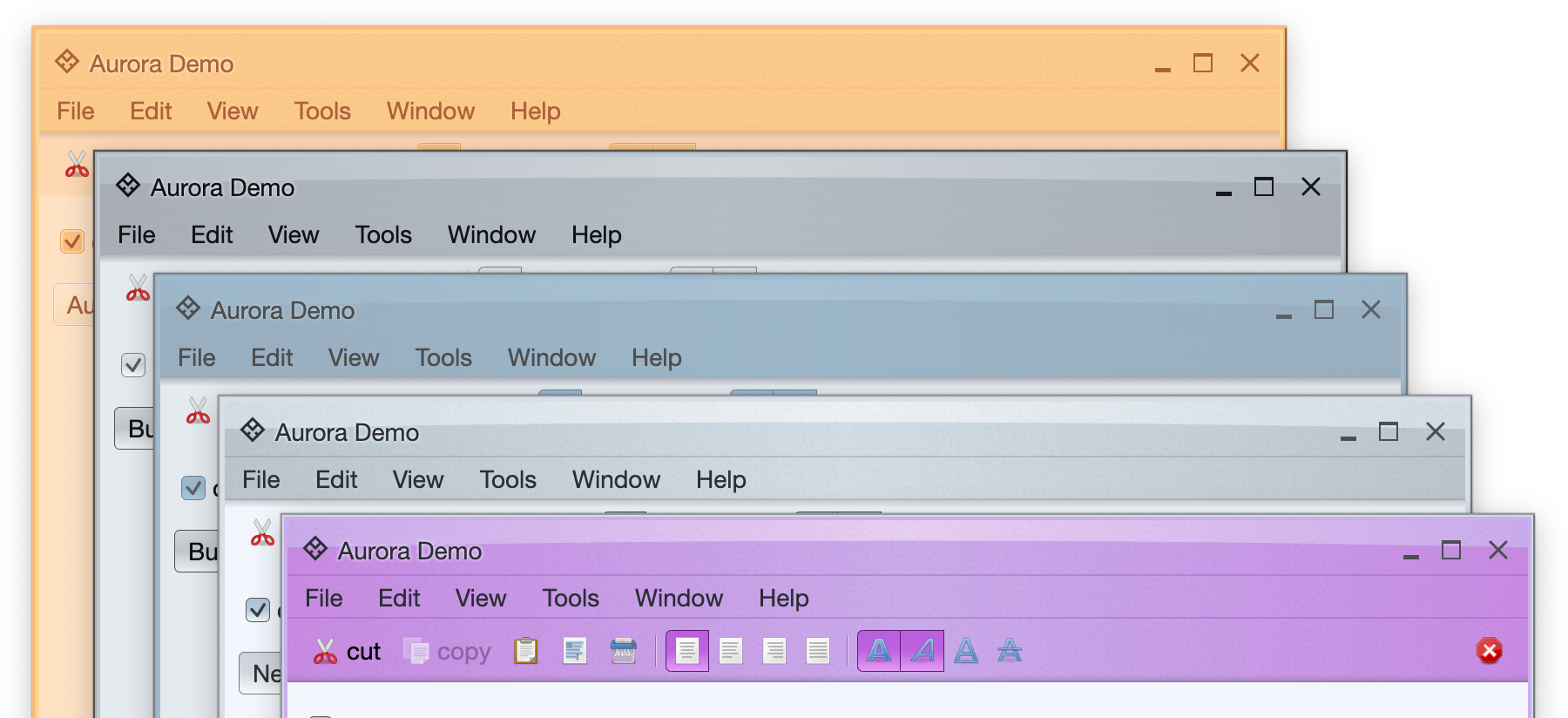

First, let’s start with a few screenshots:

Here we see the top part of a sample demo frame under five different Aurora skins (from top to bottom, Autumn, Business, Business Blue Steel, Nebula, Nebula Amethyst). Autumn features a flat color fill, while other four have a horizontal gradient (darker at the edges, lighter in the middle) overlaid with an curved arc along the top edge. If you look closer, all five also feature something else – a muted texture that spans the whole colored area.

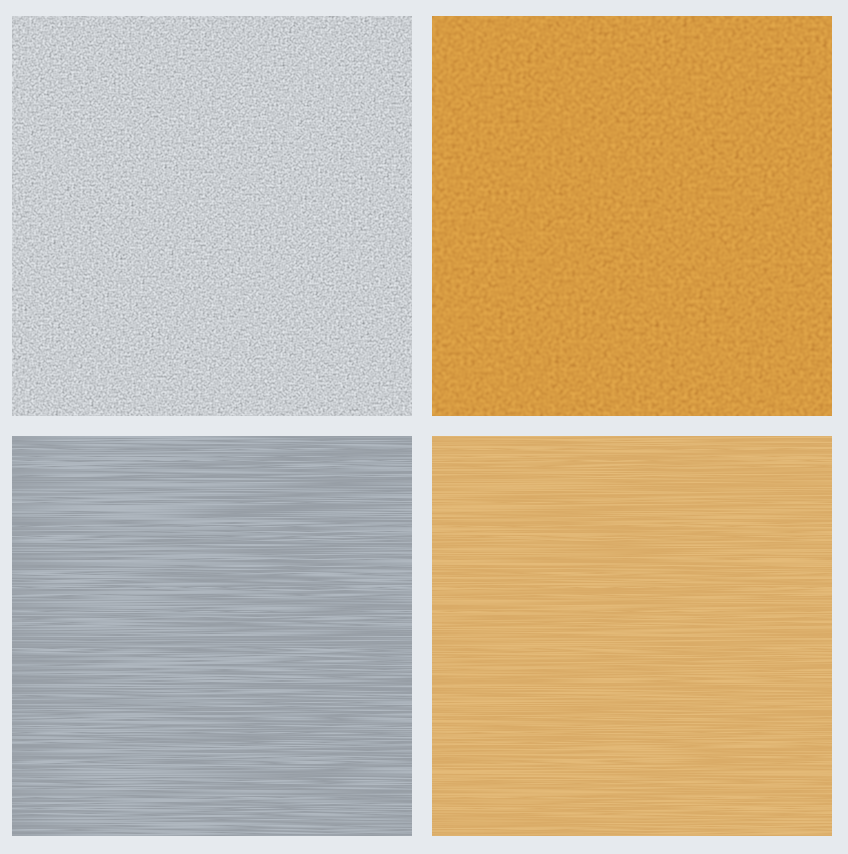

Let’s take a look at another screenshot:

Top row shows a Perlin noise texture, one in greyscale and one in orange. Bottom row shows a brushed metal texture, one in greyscale and one in orange.

Let’s take a look at how to create these textures with Skia shaders in Compose Desktop.

First, we start with Shader.makeFractalNoise that wraps SkPerlinNoiseShader::MakeFractalNoise:

// Fractal noise shader

val noiseShader = Shader.makeFractalNoise(

baseFrequencyX = baseFrequency,

baseFrequencyY = baseFrequency,

numOctaves = 1,

seed = 0.0f,

tiles = emptyArray()

)

Next, we have a custom duotone SkSL shader that computes luma (brightness) of each pixel, and uses that luma to map the original color to a point between two given colors (light and dark):

// Duotone shader

val duotoneDesc = """

uniform shader shaderInput;

uniform vec4 colorLight;

uniform vec4 colorDark;

uniform float alpha;

half4 main(vec2 fragcoord) {

vec4 inputColor = shaderInput.eval(fragcoord);

float luma = dot(inputColor.rgb, vec3(0.299, 0.587, 0.114));

vec4 duotone = mix(colorLight, colorDark, luma);

return vec4(duotone.r * alpha, duotone.g * alpha, duotone.b * alpha, alpha);

}

"""

This shader gets four inputs. The first is another shader (which will be the fractal noise that we’ve created earlier). The next two are two colors, and the last one is alpha (for applying partial translucency).

Now we create a byte buffer to pass our colors and alpha to this shader:

val duotoneDataBuffer = ByteBuffer.allocate(36).order(ByteOrder.LITTLE_ENDIAN)

// RGBA colorLight

duotoneDataBuffer.putFloat(0, colorLight.red)

duotoneDataBuffer.putFloat(4, colorLight.green)

duotoneDataBuffer.putFloat(8, colorLight.blue)

duotoneDataBuffer.putFloat(12, colorLight.alpha)

// RGBA colorDark

duotoneDataBuffer.putFloat(16, colorDark.red)

duotoneDataBuffer.putFloat(20, colorDark.green)

duotoneDataBuffer.putFloat(24, colorDark.blue)

duotoneDataBuffer.putFloat(28, colorDark.alpha)

// Alpha

duotoneDataBuffer.putFloat(32, alpha)

And create our duotone shader with RuntimeEffect.makeForShader (a wrapper for SkRuntimeEffect::MakeForShader) and RuntimeEffect.makeShader (a wrapper for SkRuntimeEffect::makeShader):

val duotoneEffect = RuntimeEffect.makeForShader(duotoneDesc)

val duotoneShader = duotoneEffect.makeShader(

uniforms = Data.makeFromBytes(duotoneDataBuffer.array()),

children = arrayOf(noiseShader),

localMatrix = null,

isOpaque = false

)

With this shader, we have two options to fill the background of a Compose element. The first one is to wrap Skia’s shader in Compose’s ShaderBrush and use drawBehind modifier:

val brush = ShaderBrush(duotoneShader)

Box(modifier = Modifier.fillMaxSize().drawBehind {

drawRect(

brush = brush, topLeft = Offset(100f, 65f), size = Size(400f, 400f)

)

})

The second option is to create a local Painter object, use DrawScope.drawIntoCanvas block in the overriden DrawScope.onDraw, get the native canvas with Canvas.nativeCanvas and call drawPaint on the native (Skia) canvas directly with the Skia shader we created:

val shaderPaint = Paint()

shaderPaint.setShader(duotoneShader)

Box(modifier = Modifier.fillMaxSize().paint(painter = object : Painter() {

override val intrinsicSize: Size

get() = Size.Unspecified

override fun DrawScope.onDraw() {

this.drawIntoCanvas {

val nativeCanvas = it.nativeCanvas

nativeCanvas.translate(100f, 65f)

nativeCanvas.clipRect(Rect.makeWH(400f, 400f))

nativeCanvas.drawPaint(shaderPaint)

}

}

}))

What about the brushed metal texture? In Aurora it is generated by applying modulated sine / cosine waves on top of the Perlin noise shader. The relevant snippet is:

// Brushed metal shader

val brushedMetalDesc = """

uniform shader shaderInput;

half4 main(vec2 fragcoord) {

vec4 inputColor = shaderInput.eval(vec2(0, fragcoord.y));

// Compute the luma at the first pixel in this row

float luma = dot(inputColor.rgb, vec3(0.299, 0.587, 0.114));

// Apply modulation to stretch and shift the texture for the brushed metal look

float modulated = abs(cos((0.004 + 0.02 * luma) * (fragcoord.x + 200) + 0.26 * luma)

* sin((0.06 - 0.25 * luma) * (fragcoord.x + 85) + 0.75 * luma));

// Map 0.0-1.0 range to inverse 0.15-0.3

float modulated2 = 0.3 - modulated / 6.5;

half4 result = half4(modulated2, modulated2, modulated2, 1.0);

return result;

}

"""

val brushedMetalEffect = RuntimeEffect.makeForShader(brushedMetalDesc)

val brushedMetalShader = brushedMetalEffect.makeShader(

uniforms = null,

children = arrayOf(noiseShader),

localMatrix = null,

isOpaque = false

)

And then passing the blur shader as the input to the duotone shader:

val duotoneEffect = RuntimeEffect.makeForShader(duotoneDesc)

val duotoneShader = duotoneEffect.makeShader(

uniforms = Data.makeFromBytes(duotoneDataBuffer.array()),

children = arrayOf(brushedMetalShader),

localMatrix = null,

isOpaque = false

)

The full pipeline for generating these two Aurora textured shaders is here, and the rendering of textures is done here.

What if we want our shaders to be dynamic? First let’s see a couple of videos:

The full code for these two demos can be found here and here.

The core setup is the same – use Runtime.makeForShader to compile the SkSL shader snippet, pass parameters with RuntimeEffect.makeShader, and then use either ShaderBrush + drawBehind or Painter + DrawScope.drawIntoCanvas + Canvas.nativeCanvas + Canvas.drawPaint. The additional setup involved is around dynamically changing one or more shader attributes based on time (and maybe other parameters) and using built-in Compose reactive flow to update the pixels in real time.

First, we set up our variables:

val runtimeEffect = RuntimeEffect.makeForShader(sksl)

val shaderPaint = remember { Paint() }

val byteBuffer = remember { ByteBuffer.allocate(4).order(ByteOrder.LITTLE_ENDIAN) }

var timeUniform by remember { mutableStateOf(0.0f) }

var previousNanos by remember { mutableStateOf(0L) }

Then we update our shader with the time-based parameter:

val timeBits = byteBuffer.clear().putFloat(timeUniform).array()

val shader = runtimeEffect.makeShader(

uniforms = Data.makeFromBytes(timeBits),

children = null,

localMatrix = null,

isOpaque = false

)

shaderPaint.setShader(shader)

Then we have our draw logic

val brush = ShaderBrush(shader)

Box(modifier = Modifier.fillMaxSize().drawBehind {

drawRect(

brush = brush, topLeft = Offset(100f, 65f), size = Size(400f, 400f)

)

})

And finally, a Compose effect that syncs our updates with the clock and updates the time-based parameter:

LaunchedEffect(null) {

while (true) {

withFrameNanos { frameTimeNanos ->

val nanosPassed = frameTimeNanos - previousNanos

val delta = nanosPassed / 100000000f

if (previousNanos > 0.0f) {

timeUniform -= delta

}

previousNanos = frameTimeNanos

}

}

}

Now, on every clock frame we update the timeUniform variable, and then pass that newly updated value into the shader. Compose detects that a variable used in our top-level composable has changed, recomposes it and redraws the content – essentially asking our shader to redraw the relevant area based on the new value.

Stay tuned for more news on Aurora as it is getting closer to its first official release!

Notes:

- Multiple texture reads are expensive, and you might want to force such paths to draw the texture to an

SkSurface and read its pixels from an SkImage.

- If your shader does not need to create an exact, pixel-perfect replica of the target visuals, consider sacrificing some of the finer visual details for performance. For example, a large horizontal blur that reads 20 pixels on each “side” as part of the convolution (41 reads for every pixel) can be replaced by double or triple invocation of a smaller convolution matrix, or downscaling the original image, applying a smaller blur and upscaling the result.

- Performance is important as your shader (or shader chain) runs on every pixel. It can be a high-resolution display (lots of pixels to process), a low-end GPU, a CPU-bound pipeline (no GPU), or any combination thereof.

Continuing the ongoing series of interviews on fantasy user interfaces, it’s my pleasure to welcome Rhys Yorke. In this interview he talks about concept design, keeping up with advances in consumer technology and viewers’ expectations, breaking away from the traditional rectangles of pixels, the state of design software tools at his disposal, and his take on the role of technology in our daily lives. In between these and more, Rhys talks about his work on screen graphics for “The Expanse”, its warring factions and the opportunities he had to work on a variety of interfaces for different ships.

Kirill: Please tell us about yourself and the path that took you to where you are today.

Kirill: Please tell us about yourself and the path that took you to where you are today.

Rhys: My background is pretty varied. I was in the military, I’ve worked as a computer technician, I’ve worked as a programmer, I’ve worked as a comic book artist, I’ve worked in video games, I’ve done front end web development, I’ve done design for web and mobile, I’ve worked in animation, and now film and TV.

It’s been a long winding road, and I find it interesting. I continue to draw on a lot of those varied experiences in video games and comic books, but also from the military as I’ve worked on “G.I. Joe” and now “The Expanse” when we’re doing large ship battles. It’s an interesting, and it’s a bit weird to think of how I got where I am now. It wasn’t something necessarily planned, but I just adapted to the times.

Kirill: Do you think that our generation was lucky enough to have this opportunity to experience the beginning of the digital age, to have access to these digital tools that were not available before? I don’t even know what I’d be doing if I was born 300 years ago.

Rhys: My first computer was Commodore 64. My dad brought that home when I was eight years old. He handed me the manual and walked away, and I hooked it up and started typing the programs in Basic. Certainly it’s not like today when my son started using an iPhone when he was two and could figure it out, but at the same time it’s not something that we shied away from.

I feel like we probably are unique in that we’ve had the opportunity to see what interfacing with machines and devices were like prior to the digital age, as well as deep into the digital age where we currently are. You look at rotary phones and even television sets, and how vastly different is the way we interact with them. We’ve been fortunate enough to see how that’s evolved. It does put us in a unique situation.

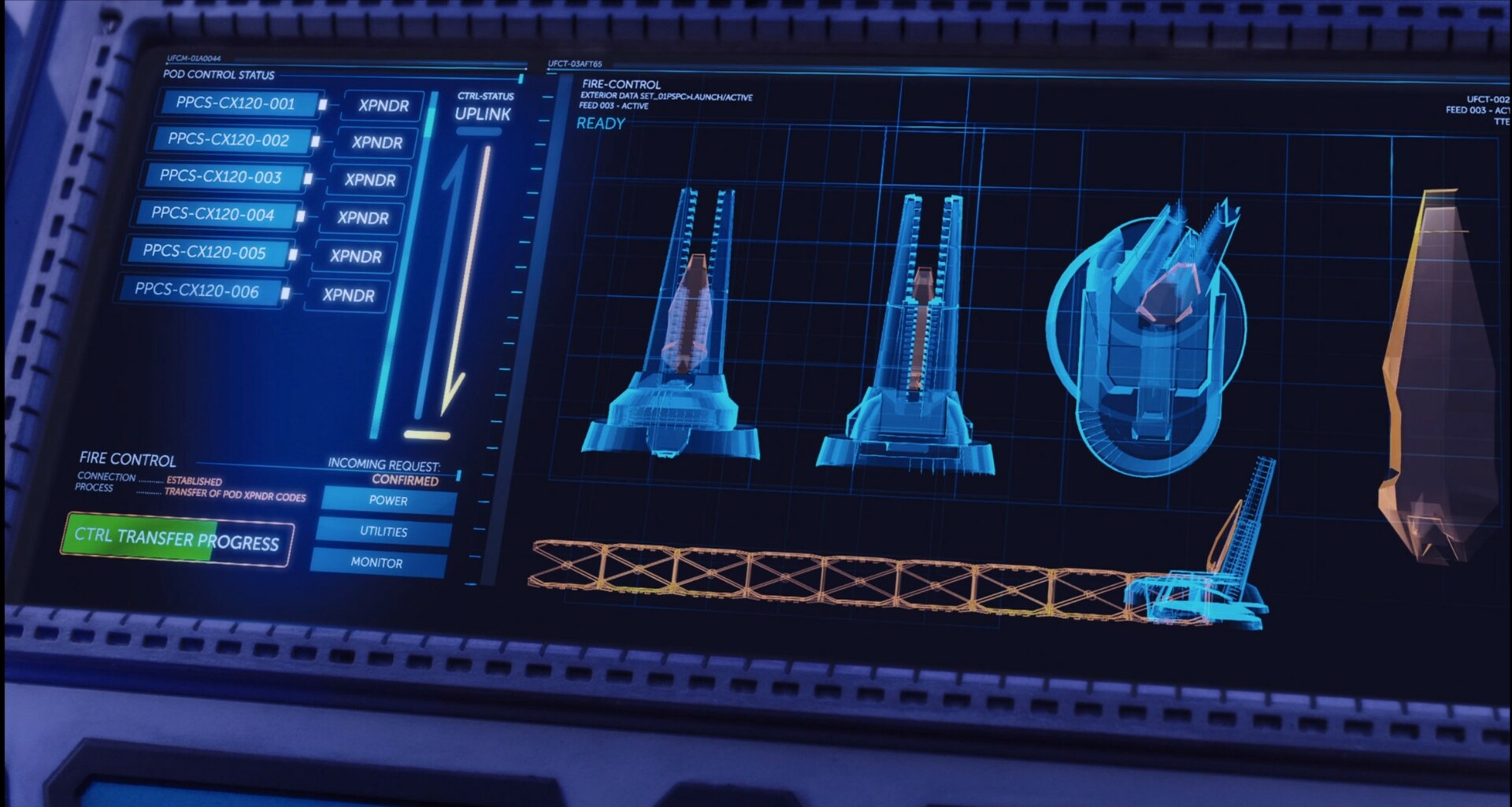

Screen graphics of the Agatha King, “The Expanse”, by Rhys Yorke

Kirill: If I look at your web presence on your website and Instagram, you say you are a concept artist. When you meet somebody at a party, how difficult or easy is it to explain what it is?

Rhys: I even have that trouble of explaining what a concept artist does with my family too. I refer to it sometimes more as concept design and boil it down to as I design things. I’ll say that for instance on “The Expanse” I’ll design the interfaces that the actors use that appear on the ships. Or that I’ll design environments or props that appear in a show. People seem to understand more when you talk about what a designer does, as opposed to the title of a concept artist.

Unless somebody is into video games or specifically into the arts field, concept artist is still a title that is a bit of a mystery for most people.

Kirill: It also looks like you do not limit yourself, if you will, to one specific area. Is that something that keeps you from getting too bored with one area of digital design?

Rhys: I find it’s a challenge and a benefit as well when people look at my portfolio. I have things ranging from cartoony to highly realistic, rendered environments. I do enjoy a balance of that.

I enjoy the freedom of what the stylized art allows. Sometimes I feel that you have the opportunity to be a little bit more creative and to take a few more risks. And on the other hand, the realistic stuff poses a large technical hurdle to overcome. From the technical standpoint, it’s challenging to create things that look like they should exist in the real world. And it’s a different challenge than it would be to create something that’s completely stylized, something that requires the viewer to suspend their disbelief.

These experiences feed into each other. I’m working in animation, and then I’ll take that experience and apply it to the stuff on “The Expanse”. I do enjoy not being stuck into a particular area, so I try to adapt. If someone will ask “What’s your own style?” I’ll say that it’s a bit fluid.

Screen graphics of the Agatha King, “The Expanse”, by Rhys Yorke

Continue reading »

Continuing the ongoing series of interviews with creative artists working on various aspects of movie and TV productions, it is my pleasure to welcome Jeriana San Juan. In this interview she talks about working at the intersection of Hollywood and fashion, differences and similarities between fashion design and costume design, doing research in the digital world, and keeping up with the ever-increasing demands of productions and viewers’ expectations. Around these topics and more, Jeriana dives into her work on the recently released “Halston”.

Jeriana San Juan

Kirill: Please tell us about yourself and the path that took you to where you are today.

Jeriana: My name is Jeriana San Juan, and my entry into this business began when I was very young. I was dazzled by movies that I would watch as a child. I watched a lot of older movies and Hollywood classics. It was the likes of “American in Paris” and “The Red Shoes”, and other musicals from 1940s and 50s. That was the beginning into feeling immersed and absorbed into fantasy, and I wanted to be a part of that.

I loved in particular the costumes, and how they helped tell the story, or how they helped the women look more glamorous, or created a whole story within the story. Those were the things I was attracted to.

From a young age I was raised by my grandmother, and she was a seamstress and a dressmaker. She saw that I loved the magic of what I was watching on screen, and also that I loved clothes myself. I loved fashion, magazines and stores, and she helped initiate that education for me. She would show me how to create clothes from fabric and how to start manifesting things that were in my imagination. So I credit her with that.

But I didn’t know it could be a career [laughs], to specifically costume design. I thought I wanted to be a fashion designer, because I knew that could be a real job that I could have when I grew up. And as I grew up, I learned that my impulses were more of a costume designer than a fashion designer, and so I moved into that arena later on in my career.

Kirill: Where do you draw the line between the two? Is there such a line between being a costume designer and a fashion designer?

Kirill: Where do you draw the line between the two? Is there such a line between being a costume designer and a fashion designer?

Jeriana: There are two different motivations with costume design and fashion design. Fashion design, to me, can be complete storytelling, but you make up the story as you design it. Costume design is storytelling with the motivation of a specific character, a specific point of view, and a specific story to tell.

My impulses in clothing are through more character-driven costume design and story-driven costume design. That’s my inclination. I feel that there are some bones in me that very much still are the bones of a fashion designer, and to me it’s not completely mutually exclusive. Those two mindsets can exist in one person.

I look back at those old 1950s movies that were designed by William Travilla and Edith Head and so many other great names, and those Hollywood costume designers also had fashion lines. Adrian had a boutique in Los Angeles and people would go there to look like movie stars, and he also designed movies. So in my brain, I’ve always felt like there’s a duality in my creativity that can lend itself to both angles.

Kirill: You are at an intersection of two rather glamorous fields, Hollywood and fashion, and yet probably there’s a lot of “unglamorous” parts of your work day. Was it any surprise to you when you started working in the field and saw how much sweat and tears goes into it?

Jeriana: Never. I come from a family of immigrants, and I’ve seen every person in my family work very hard. I never assumed anything in this life would be given to me free of charge. That’s the work ethic that I was raised with, so to me the hard work was never an issue because I’m always prepared to work hard.

Yes, it’s a very unglamorous life and career. Day to day is not glamorous at all. It’s running around, it’s 24/7 emails and phone calls, it’s rolling your sleeves up and figuring out the underside of a dress. It’s very tactile. I don’t sit in a chair and point to people what to do. It’s very much hands-on, and that never scared me at all. It excites me.

Costume design of “Halston” by Jeriana San Juan. Courtesy Netflix.

Continue reading »

Continuing the ongoing series of interviews with creative artists working on various aspects of movie and TV productions, it is my pleasure to welcome Maria Rusche. In this interview she talks about teaching cinematography to the next generation of storytellers (spoiler alert, they love film), keeping up with the technical advances, affecting social change through her stories, and the future of storytelling in post-Corona world. Around these topics and more, Maria dives into her work on the upcoming “Dating and New York”.

Maria Rusche behind the scenes.

Kirill: Please tell us about yourself and the path that took you to where you are today.

Maria: When I went to film school, I thought that maybe I wanted to be an editor. I have a cousin who worked as an editor on big comedies, and I thought that that was the part of the storytelling that I wanted to be a part of – crafting of the arc. But then I got into film school and started to learn more about how movies are actually made. I figured out what the job of the cinematographer is, which is to work with the director and the production designer to create a visual language to tell the story, and create this visual world – but also work with a team of people to actualize that vision.

That role really made sense to me, as someone who grew up playing a lot of team sports. It’s a leadership position, but really it’s about working with and delegating to a team, and collaborating with the team. That was an area of the storytelling that I fit into really well. So I got into cinematography when I was in school, and I never looked back.

Kirill: Do you think this field does not work well for people who don’t collaborate well with others? Perhaps people that have strong ideas that they are not willing to compromise on?

Maria: There can be a bit of a stereotype of this auteur who rules with an iron fist, and has their vision and they won’t compromise. But I’m not sure how true that actually is.

The best directors and cinematographers can understand what the vision is that they’re trying to achieve, and they’re able to encourage the people around them to contribute their own ideas. And then they’re able to filter what works well for the project and what might not work well so that there’s a cohesiveness across the project. There’s absolutely no way that one person can execute everything, and I mean that literally. They’re not moving the lights around, they’re not moving the camera themselves. They need people to work with them, and if you can’t work with the team, I’m not sure how great of a product you can ultimately make.

Cinematography of “Milkwater” by Maria Rusche.

Kirill: There’s so much great storytelling that has been happening in the last few years, especially on streaming services. Do you feel that there’s more space for storytellers of different backgrounds to have their voices heard?

Maria: I’m definitely excited by the democratization of voices getting opportunities. There’s a lot of streaming services that are starting to produce content, or at least give a platform for a wider variety of content to be seen. Some people worry that it’s too much content, but I think it’s still true that the good stuff floats to the top. We are seeing a wider variety of storytelling opportunities for people who didn’t traditionally get opportunities, and by opportunities I mean financing, compared to a few years ago.

I feel that there’s still a gatekeeping aspect of it. It’s still these streaming services or production companies that are choosing who gets to tell those stories, and what stories they deem are authentic enough or palatable enough. The “diverse” stories that we’re getting are still the ones that streaming services deem palatable or appealing to an audience. I would say I’m excited, but with that caveat.

Kirill: Is there a space for crowd-funded initiatives that are so popular in the gaming world, or in the world of gadgets – on platform like Kickstarter, or are these productions a little bit too expensive for that?

Maria: It’s a little bit expensive. You are seeing some crowd-funded independent movies. You can make a movie on a smaller budget compared to 20 years ago, and maybe those movies are serving as a way for a new director to get their foot in the door and get a little bit of attention. But most of those independent movies still end up being made by people with some connections to financiers in some way, or at least an ability to call a few people and scrape together a couple hundred thousand dollars to make their movie. That model doesn’t really help those who don’t have any access to wealthy donors.

I have not seen a true crowd-funded movie from someone who has gotten a hundred thousand people to give two dollars each. There’s still some issues there.

Cinematography of “Might” by Maria Rusche.

Continue reading »

![]()

![]()