Continuing the ongoing series of interviews with creative artists working on various aspects of movie and TV productions, it is my pleasure to welcome Imanol Nabea AEC. In this interview, he talks about the transition of the industry from film to digital, working through the global pandemic, the potential impact of generative AI on the industry, and the variety of screens in our lives. Around these and more, Imanol dives deep into his work on the two seasons of the fan-favorite “Warrior Nun”.

Kirill: Please tell us about yourself and the path that took you to where you are today.

Imanol: I was born in Spain in 1971, when I finished high school I went to an engineering college. I always wanted to become a photographer, but I never thought about working in the movie industry because I didn’t know anyone in that world. At some point I quit the engineering school and started at an image and sound program in a technical public school. That was around 1992, I started shooting short movies with some friends, and there was going to be a movie in my hometown Bilbao, and a friend of mine told me that they needed a video technician to work with the Hi8 recorder of that time. I did two movies as a video technician, and after that about 10 years as a camera second assistant, 13 years as a focus puller, shooting second units as a camera camera operator – and always thinking about being a director of photography. I did short movies, I did a lot of photography for myself, and that’s my background. I never thought about working in this industry, but suddenly I was there, and I was fascinated by it. I love it.

Kirill: How was the transition from film to digital? Do you feel that something has been lost during that transition?

Imanol: I don’t remember exactly when it was. At that time I was pulling focus and I lived it as a soft transition, but I was having conversations with colleagues in the industry talking about this transition, and I remember saying that it was not going to happen, that things would continue as they were with film. Film wasn’t going to die. I guess I couldn’t – or didn’t want to – see the reality.

Film has such a beautiful texture, and I couldn’t see how digital was going to take over. Sometimes I watch a movie, and I see something that is there, and you can’t put your finger on it, but whenever you look at how it is shot, you realize it is shot on film. I still think that film has something that digital doesn’t have, and not just the texture. You see highlights, you see how different colors interact with each other.

But then there’s the other side of it. I worked as a focus puller on about 50 movies, and every day I would be waiting to hear from the film lab to see if there was anything out of focus or too soft. As a focus puller I could sleep much better with digital than with film.

Things are so much faster with digital. You have to shoot much faster. You don’t have those breaks you had when you were reloading the magazines or checking the gate. The timing is different. In a way, the set has changed. Everybody can see what you are shooting, from the director and yourself to other people that have access to the monitors. Now everybody can instantly form an opinion, which is not necessarily a bad thing. It is just how it is.

The set is not as silent as it used to be. Negative costs money, and each take was money spent, so everybody kept quiet once the camera started rolling. Right now there is a sense that digital is free, that you can keep on shooting and shooting. It costs money, but the economics are different. Every roll of film was money, and once you use it, you can’t overwrite anything on it. There was a mutual respect from everyone on the set.

So that’s the two biggest things that have changed – the texture and the way of working. Focus pullers today can do their job sitting in a room watching a monitor – and that was simply impossible back in my time. It has changed, not for better or worse, but simply different. At the end, the basics of the light are still the same, but you have to adapt to how the set works now.

Kirill: When you meet somebody outside of your industry, and they ask you what do you do for a living, how do you convey the complexity of the different roles you play on the set?

Imanol: I would say I translate the script into images playing with my tools – which are the light and the camera, and that also I am the director’s right hand, or at least I try to be. I help a director to tell the story. I talk with all the departments that are involved in what appears in the frame because all of us create the visual image of the film.

For me it’s crucially important to understand where the director wants to go with the story, what he wants to tell with the camera and the light. Every director has a different way of facing a story, and part of my work is to adapt myself to that, and I love it because it makes me improve and learn from different points of view.

Continue reading »

Continuing the ongoing series of interviews with creative artists working on various aspects of movie and TV productions, it is my pleasure to welcome back Owen McPolin. In this interview, he talks about changes in technology and lighting, the impact of Covid on the industry in the last few years, the potential impact of generative AI on the industry, and what advice he would give to his younger self. Between all these and more, Owen dives deep into his work on the first two seasons of the gorgeous adaptation of a seminal sci-fi classic “Foundation”.

Owen McPolin on location in Fuertaventura for Beggars Lament sequence in “Oonan’s World” episode. Courtesy of Owen McPolin.

Kirill: Since we last talked back in 2014, what changes have you seen in your field since then, perhaps around the evolution of cameras and lights, or maybe where these stories are told?

Owen: The biggest thing that has changed has been the type of lighting we have used in the last number of years. Everything has transitioned to LED lights. It’s great for the environment, it’s more reliable, it’s more accurate compared to the conventional tungsten and HMI lights. I now have the ability to cue lighting and to build entire cues of lighting far more easily. Now, not only you can change a whole array of lighting systems and bring them to bear on a scene, but you can also change colors and contrast, you can move the heads, and they can all be controlled centrally from a desk. We used to be able to control dimming, but now we have so much more expansion of control, and that has affected me and my work.

Back in 2019 I did a job in Budapest for Netflix on the show “Shadow and Bone”, and we had a fantastic local gaffer called Krisztián Paluch. He has a team of expert and experienced board operators in the newer LED systems. One day we found ourselves in a scene where a number of characters had come into a forest environment, and the director of the episode wanted to rehearse the action in this large denouement scene in one. So together, Christian and I, we had developed eight or nine large cues to take place over. That sequence took about 15 minutes of screen time after it was all cut together, and when we were done with it, he told me that it had more cues in it than any of the “Blade Runner 2049” sequences that he worked on with Roger Deakins.

I told him that we would have never have been able to do that a few years ago, and he agreed. He had a small remote control queuing system handheld device, and he used that to trigger the cues as he stood beside me and the director on the set, relaying straight back to the Wi-Fi system on the dimmer board operator. Some of the cues were needed to be so accurate that Krisztián needed to stand in front of the performance as they went, because there was a slight lag in some of the transmission back to the monitors. and you’d miss it.

We needed to generate a large amount of light around Alina Starkov’s character, and to maintain that ability of hers while the antihero came in who generated a lot of darkness. The whole queue is a ripple of darkness that runs over the set. And there was also gunfire and other elements, a lot of complicated cues all in one sequence. That was a real eye-opener for me. In a way my job is more difficult, but in another way, far easier. I can check with the director on what they want to happen in a scene, and build cues without feeling that it might be unreliable. It has opened up confidence to do sequences that, just a number of years ago, I would have thought to have been out my reach artistically, creatively, and technically.

As far as cameras go, there’s always new models coming out. You have more megapixels and larger resolution. Now 4K is the base level, and they’re talking about higher resolution cameras, and larger exposure latitudes within those new sensors. New Sony models have hyper-accurate ISO depths of 26,000 ASA, which is mind-boggling. This new sensor technology hasn’t washed over the dramas that I’ve been doing at the moment, but I expect that to happen soon.

There is obviously AI on the horizon. We might not necessarily see eradication of certain processes on the set, but certain efficiencies are expected. There are emerging AI systems for storyboard renderings. There will be machine learning for lighting systems, and that’s going to make a big difference. And then you can start thinking about artificial general intelligence (AGI) for the creation of sequences within a show. That can make a huge difference in pre-vis where VFX and real-time capture come to planning. Say, a director wants to pre-vis a space battle sequence. Today it takes a VFX house a lot of man hours, and there’s a lot of revisions to every such sequence again and again. With AGI you might form that storyboard much quicker, and then tweak it as well.

Continue reading »

Continuing the ongoing series of interviews with creative artists working on various aspects of movie and TV productions, it is my pleasure to welcome back Patrice Vermette. In this interview, he talks about productions that he’s been working on since we first talked in 2016, making it through the global pandemic, and the potential impact of generative AI on the industry. Around these and more, Patrice dives deep into his work on the magnificent “Dune: Part One” and “Dune: Part Two” that are reshaping the landscape of cinematic sci-fi storytelling.

Patrice Vermette on the set of “Dune”, courtesy of Warner Bros Entertainment Inc

Kirill: Welcome back, Patrice. We spoke back in 2016 about your work on “Sicario”. How were these last eight years for you?

Patrice: 2016 was the year that “Arrival” was released. The movie was a success, earning 8 Academy Award nominations including 1 win for sound and provided me my second Oscar nomination.

Between then and now, I also had the opportunity to work with different directors. Nash Edgerton on “Gringo”, Hany Abu-Assad on “The Mountain Between Us”, and Adam McKay on “Vice”. It’s great working with different people. It gives you a different perspective about film making and it puts you outside of your comfort zone – which is great.

In early February 2018 Denis asked me if I’d be interested in working on “Dune” with him. We embarked on this amazing year and a half journey.

Shortly after, I was given the opportunity to collaborate with Alejandro G. Iñárritu on “Bardo”, but when we were only three weeks from the camera to roll, the pandemic hit, and we were sent home. It was quite heartbreaking, but it was obviously nothing compared to what was going on in the world.

The world had changed overnight. It was a question of reinventing ourselves, learning new technologies, trying to understand how we could go about doing our work. I was already accustomed of doing distant work during soft prep but this time it was a question of being able to manage it for a greater period. During the pandemic, I was extremely fortunate to be able to work on the development of different projects while staying home with my family. “Tron: Ares” was one of them. I met Garth Davis through this experience. We had a lot of fun, but unfortunately, it did not go further than three months.

After the Tron adventure, Garth Davis asked me if I would be interested in continuing our working relationship on a smaller project which was “Foe”. A beautiful film shot in Australia. Soon after the release of Done Part 1, Part 2 was greenlit and I was off on a new journey, reuniting with Denis Villeneuve.

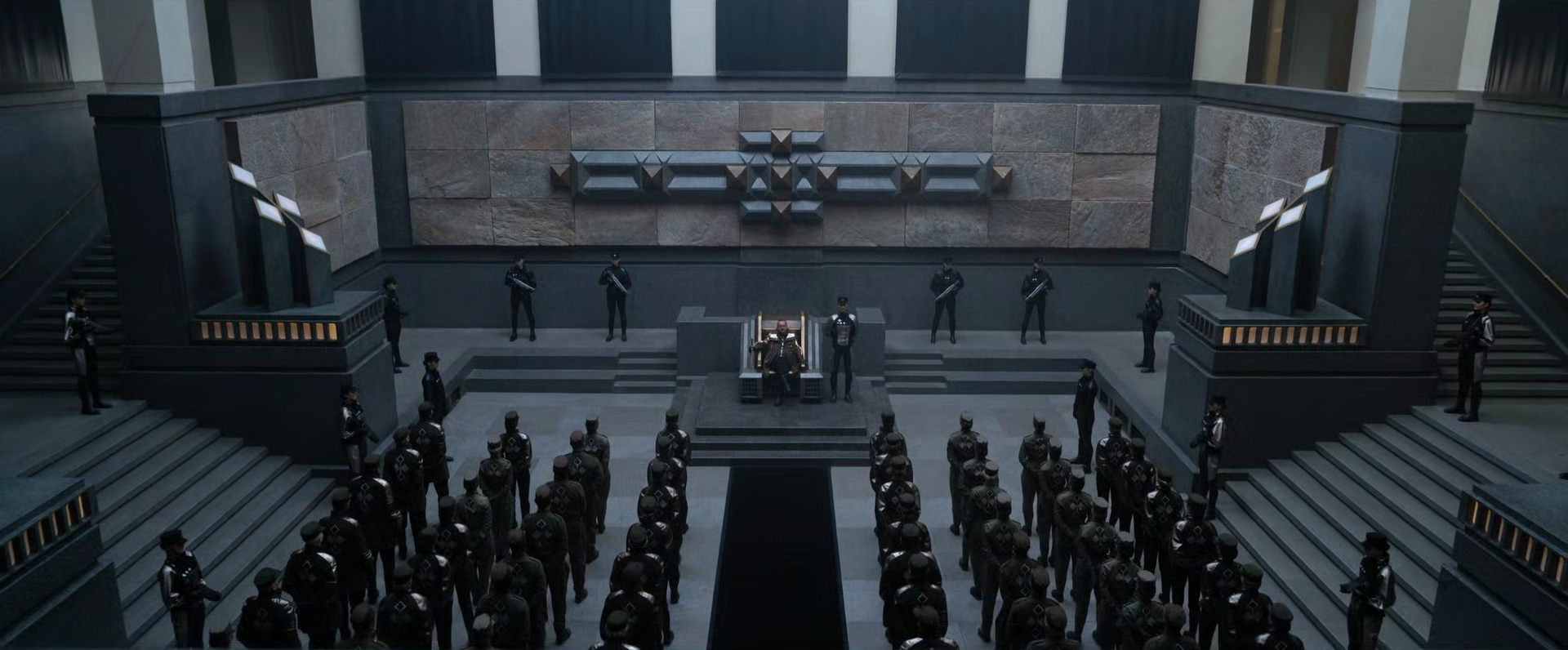

Production design of “Dune” by Patrice Vermette, courtesy of Warner Bros Entertainment Inc

Kirill: There’s so much material that is packed even into the first book of the “Dune” series, and for a long time the series has been considered unadaptable to the screen, or perhaps uncontainable in a sense that there’s so much in there. How do you choose which parts to focus on and which parts may be less important in this adaptation?

Patrice: The book “Dune” was a fantasy project of Denis Villeneuve. He had read the book when he was 13, and had done some storyboards with his best friend when he was 15. So we approached “Dune” with his vision of the book.

From the get-go it was obvious that there’s too much in the book to fit in one movie and Denis took the decision to split the book in two movies quite some time before I got involved in the project. It’s really Denis’ cinematic adaptation. He worked with the scriptwriters on distilling the elements from the book to make it easier to understand for the viewer. Some elements needed to remain in the book. That was all Denis, the scriptwriters, and the producers.

When I started working on the film, I started by reading the book again. I had first read it when I was a teenager as it was quite popular back then. I understood the responsibility I had towards the material but also towards Denis as it is such an important book to him. I wanted to go back to the source, and by doing so, I took notes and found some interesting elements that gave me clues on how I should approach the design.

Those clues are not necessarily mentioned in the script, but it’s there in the book. Frank Herbert doesn’t give all the answers. Even though you have the lexicon with all the terms used in the book, it doesn’t go much into details. As an example, it describes ornithopters as ships with wings that flap like birds. You really need to go through the book and distill the little clues before approaching how the things should look and be designed.

Everything in the design of the film is a reaction, a conversation with the natural elements of the planet, the economics of the planet, how those people live. It’s what makes up a culture and how I approached it. For Denis and I, design for design cannot exist. Design needs to support storytelling, inform us of the past as well as the future. Working with him is such a pleasurable experience because we have a shorthand. There’s no hurdles. We move forward all the time, and that allows us to go deeper into the details.

Production design of “Dune” by Patrice Vermette, courtesy of Warner Bros Entertainment Inc

Continue reading »

Continuing the ongoing series of interviews with creative artists working on various aspects of movie and TV productions, it is my pleasure to welcome Bárbara Pérez-Solero. In this interview, she talks about the transition of the industry to digital tools over the years, working through the global pandemic, the potential impact of generative AI on the industry, and finding inspiration for her work. Around these and more, Bárbara dives deep into her work on the two seasons of the fan-favorite “Warrior Nun”.

Kirill: Please tell us about yourself and how you started in the industry.

Kirill: Please tell us about yourself and how you started in the industry.

Barbara: It was not a purpose in my life. I come from a very creative family. My grandfather was a renaissance man and a pioneer in the advertising industry. He painted, wrote for newspapers, wrote poetry, played violin and piano, and he was designing all these incredible ads back in the ’30s. My father followed his path and he had his own advertising agency. So I was always surrounded by creativity.

I loved to paint since I was very little, and when I grew up, I wanted to study fine arts. I worked in contemporary art for a few years; I had a friend who was a movie producer, and she invited me to a shooting. She told me that I had everything that was required to do that job. I love literature and I love storytelling, and I did love cinema too. So I went to that shooting, and completely fell in love since the first moment. And I’ve been doing it for the last 32 years [laughs].

Kirill: If you look at how things were back 30 years ago and how things are now, what would be immediately recognizable in the art department and what would be significantly different?

Barbara: It’s all about technology. When I started, we didn’t even have cell phones. You were calling your boss from a public phone down the street, and all the phones were broken, and you were constantly out of coins [laughs]. It was a complete nightmare. You took pictures, and it took more than a week to develop them. And then it was down to one day, and then it was only two hours! The process was much slower than now. Nowadays it’s a fast world, and you have to react fast. You never have enough time even on the big projects.

We used to shoot on 35mm and film was expensive. You didn’t shoot as much because of the cost. Now you can be shooting for hours and hours, and it costs almost nothing in comparison.

We didn’t have any computers. Everything was drawn by hand, and then redrawn by hand to incorporate changes. Everything took a lot more time. Now I can be riding in a van, and sending images to my art director with concept design or whatever, and you’re moving and designing at the same time as you’re scouting.

Set builds on “Warrior Nun”, courtesy of Bárbara Pérez-Solero.

Kirill: Is there anything missing when the new generation comes in and it’s fully digital, using a stylus and a tablet without having learned how to put pencil to paper?

Barbara: I wonder about this every day. I’m turning 59 this month, and I did embrace digital when it came along. You have to embrace new technology, because it gets complicated if you don’t. It’s been years since I’ve done a concept drawing on paper myself.

I see young directors that are starting to turn their backs to technology. They don’t want WhatsApp, they don’t want that immediate exchange when they are in the field. But on the other hand, it’s useless to push back against technology. We cannot stay as we were forever, with that drawing table and paper. I wish we could. I’m nostalgic like everyone. Even the young people come around to loving it, but it’s not possible anymore. Technology is incredible. To be able to draw something this fast, and to share it with other people in that moment, and to have a conversation – that allows you to find the answer you’re looking for. You can work with your carpenter or your painter right there in that moment.

On the other hand, it is happening so fast now. That’s the worst side of it. You almost don’t have any time to think about anything. I used to smoke a lot, and it used to be that after I finished a set, I would go outside, light a cigarette or two, and take a moment for myself to think about how it feels, what went right and what went wrong. There’s no time for this anymore.

I see so many talented young people. I try not to complain, because I don’t want to feel like a grandma [laughs].

Set builds on “Warrior Nun”, courtesy of Bárbara Pérez-Solero.

Continue reading »

![]()

![]()