Continuing the ongoing series of interviews with creative artists working on various aspects of movie and TV productions, it is my pleasure to welcome Adam Reamer. In this interview, he talks about the roots of the horror genre, building worlds to support the story, the rise of generative AI tools, and career development. Between all these and more, Adam talks about his earlier work on “Grimm” and “Insidious: The Red Door”, and dives deep into what went into making “Immaculate”.

Kirill : Please tell us about yourself and the path that took you to where you are today.

Kirill : Please tell us about yourself and the path that took you to where you are today.

Adam: My name is Adam Reamer, and I’m a production designer. I didn’t start early on a path intending to pursue film, but I do feel like a lot of the turns I took along the way did lead me there – in terms of developing a sensibility and a skill set that has been useful to me in the film industry.

I was interested in visual arts from a very young age. I was always crafting, building, making things with my hands, whether it was Lego toys or anything in the physical world of making. I got my degree at Penn State in architecture. When I moved to New York after graduation, it was shortly after 9/11, and the building and architecture economy had crashed. It wasn’t possible to find jobs for new graduates in the field, so I answered an ad in The New York Times for a set carpenter.

I wound up with a company called Readyset. I worked there as a set builder and scenic painter for many years, and eventually I took over management and design at that shop. We served the still photography industry, but also to events and retail display and trade shows – a lot of environmental design. That was my first introduction to scenic design more broadly.

When I left New York, I got into design-build architecture with a guy I met out here in Portland, Oregon. We were designing and building remodels and some new houses for a couple of years. As I was doing that, there was a TNT television show “Leverage” that came to Portland, and they needed a set designer, which in the industry is a draftsman of construction documents for set building. I got that job through a friend of a friend, and then I fell in love with the work. That started my career.

I moved up through assistant art director and art director, and I ended up on a series called Grimm, which was a fantasy / police procedural. I art directed that for about 4 years, and then I was bumped to production design. That was my first credit in the role, and what allowed me to get representation, and start pursuing feature film and projects outside of the Portland area.

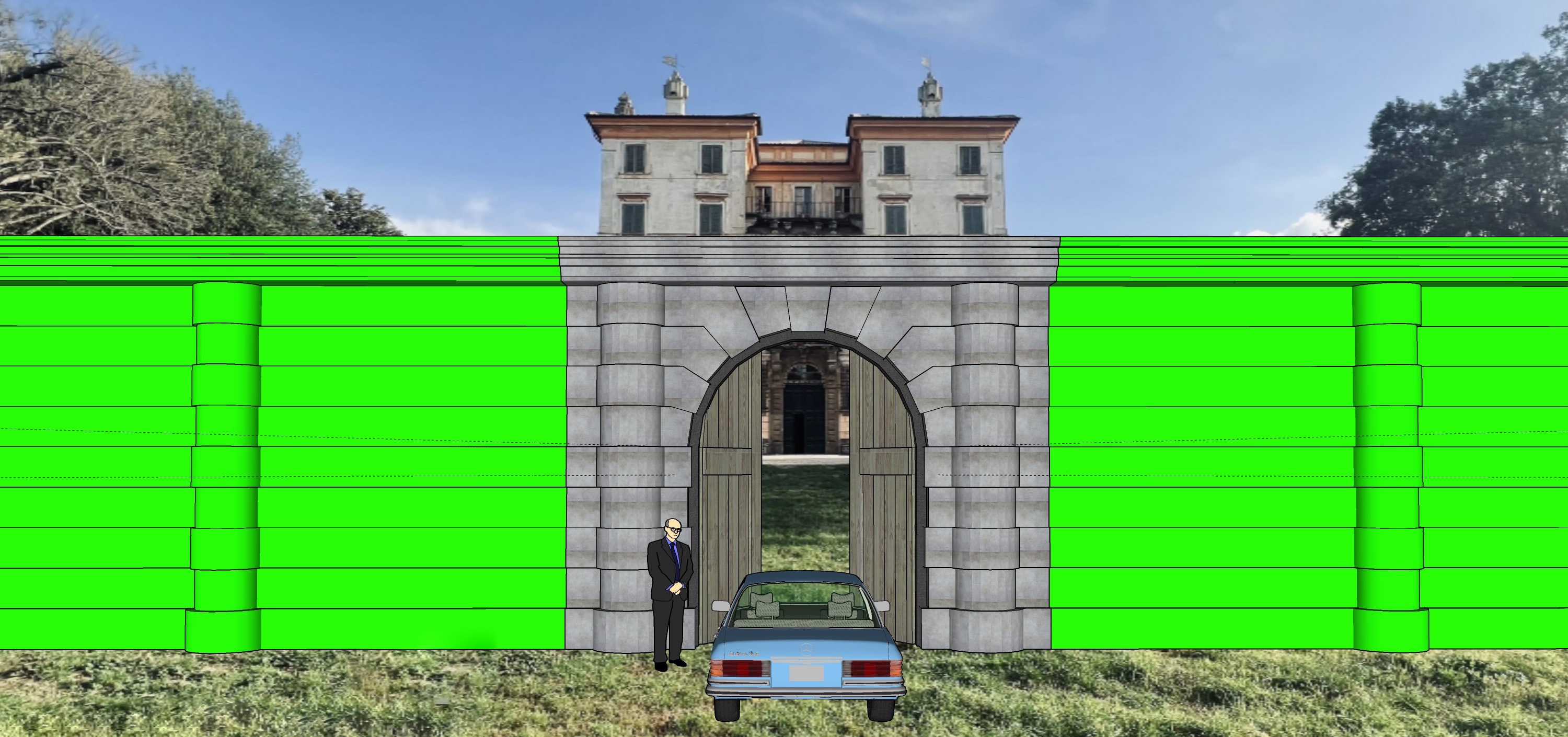

External walls of Villa Parisi (principal location for the convent) as reference for the gate build. Courtesy of Adam Reamer.

Kirill: Do you remember if there was anything surprising when you joined the industry and you saw how it looks like from the inside? Hollywood likes to present itself as this glamorous industry, with red carpets and beautiful people and parties, but that’s probably for the top 1% of the top 1%.

Adam: I was immediately surprised that the people making television weren’t like the people on television. It’s such an obvious thing if you think about it, but back then as soon as I started doing the show, that’s what I saw – people being the nuts and bolts of the industry. It’s all different kinds of people, from creatives to accountants to people that drive trucks. It’s not all glamorous people. It’s a wide variety of personalities and backgrounds that come together. That was a bit surprising.

Blocking diagram for the construction of the convent gate on location of Villa Parisi. Courtesy of Adam Reamer.

Kirill: It’s always been an industry that has had its ups and downs as the business around it changes, but it’s also always at the forefront of technology changes. If you look at your first 15 years in it, what stands out for you in terms of changing technology in your craft?

Adam: I came into television at the time when people were first starting to make the full transition to shooting digital. I wasn’t in the feature world at that time and I don’t know where they were, but I think that they probably followed a little later. Initially, the big motivation for the digital for some television productions was affordability, and economy of speed and production, and turning around dailies and content. I wasn’t part of the industry before that shift started.

I will say that in the 15 years that I’ve been doing it, we’ve seen the industry change dramatically around streaming services not only offering content, but then starting to create their own content. We’ve seen the gradual shift away from the traditional studio TV model of doing episodic series with 22 episodes, which is rare now. That’s what we were doing on “Grimm” even 8 years ago with NBC, and now most of it is moving to streaming models with shorter production runs, and different production strategies like block shooting. It’s less related to the technology of the actual filmmaking, and more about the distribution format.

The contemporary modes of the VFX production were already pretty well established by the time I started. I’ve seen that grow and become more technically simplified in ways, and it’s much easier to shoot for VFX production than it was 15 years ago. The technology is so much better in terms of how it can do isolation and animation, and everything is way more streamlined as a process. It’s nice, because it offers you the opportunity to use that tool without it being egregious in terms of budget.

The built part of the convent gate on location of Villa Parisi. Courtesy of Adam Reamer.

Continue reading »

Continuing the ongoing series of interviews on fantasy user interfaces, it’s a delight to welcome Danny Ho. His path in the industry started almost 30 years ago, at the cusp of the transition from pre-recorded video decks to fully interactive computer generated graphics. Under his leadership, Scarab Digital is a monumental presence in the field of screen graphics (and well beyond), with over a 100 productions under its belt, including more than 1,000 episodes of some of the most memorable television in the last couple of decades, from “The X-Filed” to “Charmed”, from “Sanctuary” to “Siren”, from “Yellowjackets” to “Monarch”, as well as the entire span of the DC television universe in the last 12 years – “Arrow”, “Supergirl”, “Legends of Tomorrow”, “Batwoman”, “The Flash”, and “Superman & Lois”.

In an almost impossible task to fit all of this into one interview, Danny talks about those early days of computer generated graphics and the evolution of hardware and software stacks, challenging his artists to make an impact with their work, how much resolution is too much, the impact of Covid, and the looming emergence of generative AI tools.

Kirill: Please tell us about yourself and the path that took you to where you are today.

Kirill: Please tell us about yourself and the path that took you to where you are today.

Danny: It was back in the 24-frame CRT computer playback days, as practical on-set video playback was already established. There was little post work, and most of it was making real graphics on set, right at the cusp of pre-recorded rendered output from a video deck. You would play linear video, there was no interactivity, and production was used to that. It was done on a three quarter inch or Betacam decks, fully synced to an actual CRT that was synchronized with the film camera.

I got exposed to that through the company that was doing that process on the computer side of it and starting early explorations into interactivity. My buddy was helping someone else do it, and he didn’t mind company. I would go with him to the set and he was, of course, designated to do the work. In between takes I would watch him rush, and try to cable things up, and go to the monitor, and connect to the computer. You’re always under a timeline, and there’s always a struggle of a sort. So of course, I’m not going to sit there and watch him [laughs]. I would go and help him and connect everything until it was all done – and then the actors would work with his stuff.

As I watched and observed, I started thinking that these guys have something here. This is not going to go away. This is going to become more demanding, because we’re natural geeks. We just know how to do this. The old legacy was purely video. They have no idea how to make anything interactive. And sure enough, they landed “The X Files” season two. From there Chris Carter [the creator of the show] became the hottest thing and started doing other shows like “Millennium”, and I ended up working on all those spin-offs for Chris. That was the training grounds for growing this whole thing and taking it to the next level.

Those three quarter inch decks and BetaCam decks were big pieces of equipment, and they had hard cases on them. If you had more than one source, you needed more than one deck, and you have to help carry these things around. I could see the guys who had the market doing video would eventually converge, and you would have a computer that would be able to eventually play video. You could see that coming, even if it wasn’t immediate. It was years away at that point.

I was able to do both. I worked with the video guys and I worked with the computer guys. Back then I did everything as one person – I would coordinate or shoot on set during the day, build graphics at night, then do the whole cycle again the next day. I was burning the candle at both ends. And eventually, as I coordinated projects, you build a network and you solve other people’s problems. So they give you a call and say “Hey, can you help us on our show?” I can say that I was one of the only ones at the time that could do both – I can do the computer and I can do the video playback stuff. The video guys didn’t want to learn the computer side, so they would recommend this fellow who’s well-known in the community. His name is Klaus Melchior and he cornered the market in terms of video.

I knew there would be a certain point where he was going to sail off to the sunset and retire, and sure enough he did. I was happy for him that he was able to retire, he’s an awesome guy. So we picked up the pieces and took the reins for this transition to using computers to play video interactively.

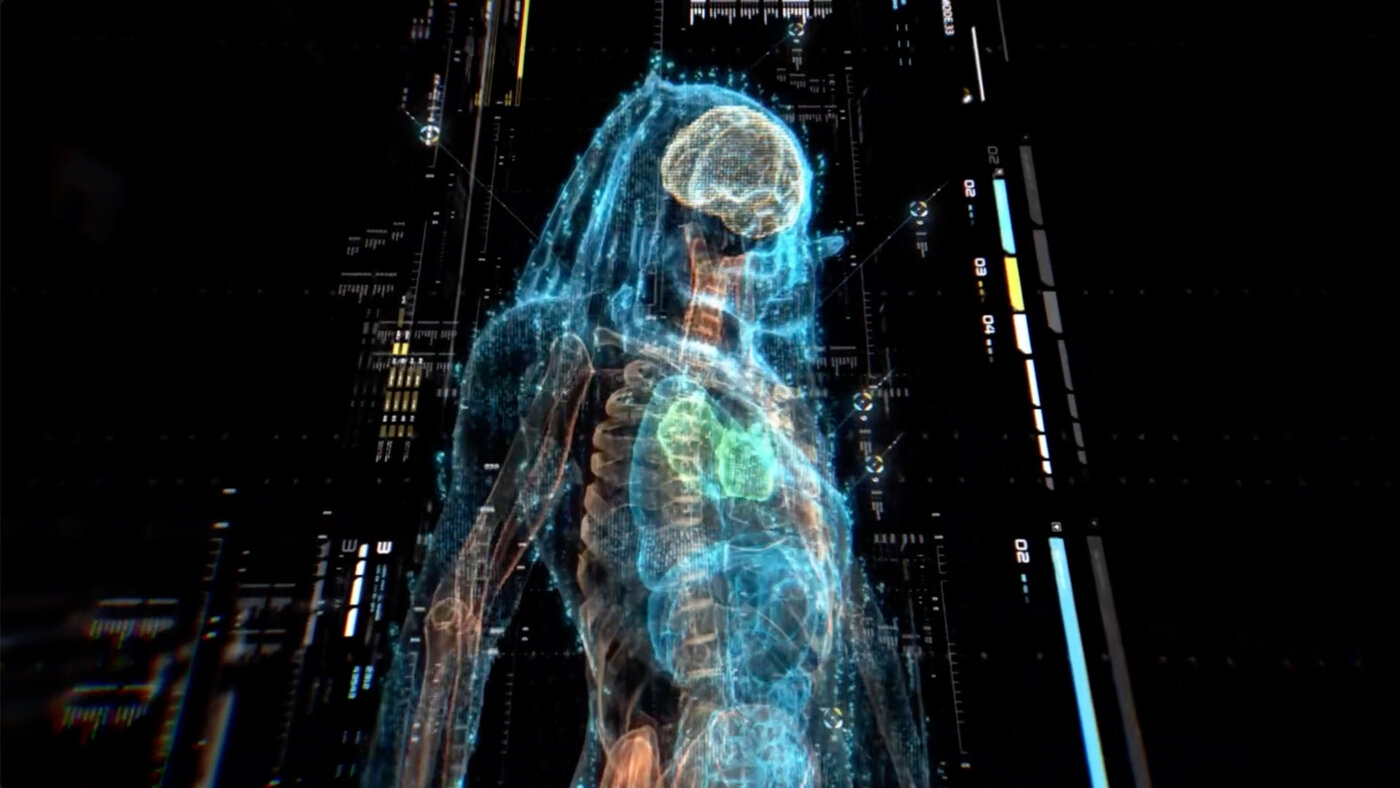

Screen graphics for “The Predator” (2018), courtesy Danny Ho and Scarab Digital.

Kirill: Was there a particular point in time where it felt that computers are powerful enough to take over back then?

Danny: My brother had an internship with Alias Wavefront that later became Maya. I remember visiting him and then he showed me a little trailer, just like we see them every day now, a trailer of a movie. It was playing full real time on an SGI computer, and it was so foreign of a concept to see a video file playing on a computer. It was full resolution and completely smooth. Unbelievable at the time.

It gave me a taste of what the future was going to be on a typical regular computer. It was mind blowing at the time, but of course to us now it’s nothing.

Kirill: How wild is it to look back and remember those days and look at your desk now?

Danny: It’s unbelievable [laughs]. Your phone has more compute power than what the computers were using at the time. If you take the concept that every year you have compute power doubling, it’s pretty staggering.

That’s somewhat of my sweet spot of what I bring to a company. I was able to see where the trends are going, and what the demand might be, and what people might want based on what’s happening now and what’s possible in the future. That is how I’ve grown the business, trying to always stay ahead, looking at what tools might be out there.

There are times I take tools that are completely not meant to do anything related to film or graphics, but they might have to fulfill a purpose for us. We adopt them into the workflow, and we’re always eager to improve and make what seems impossible, possible. Look at the visual effects these days. At one point it couldn’t do plastics and things that look reflective that well. And then later it can do fire and water. It is always progressing. There was a time back then when I was contemplating our company to also do visual effects. Do we do visual effects or do we stay in interactive motion graphics? If you think about what the producer wants, and consider what is doable in VFX. Then you graph VFX against what the producers want vs achievability, they are running almost in parallel, and almost never cross. It’s very difficult to exceed the expectations of a producer for any visual effects. It’s definitely more attainable now, especially when you throw enough money at it.

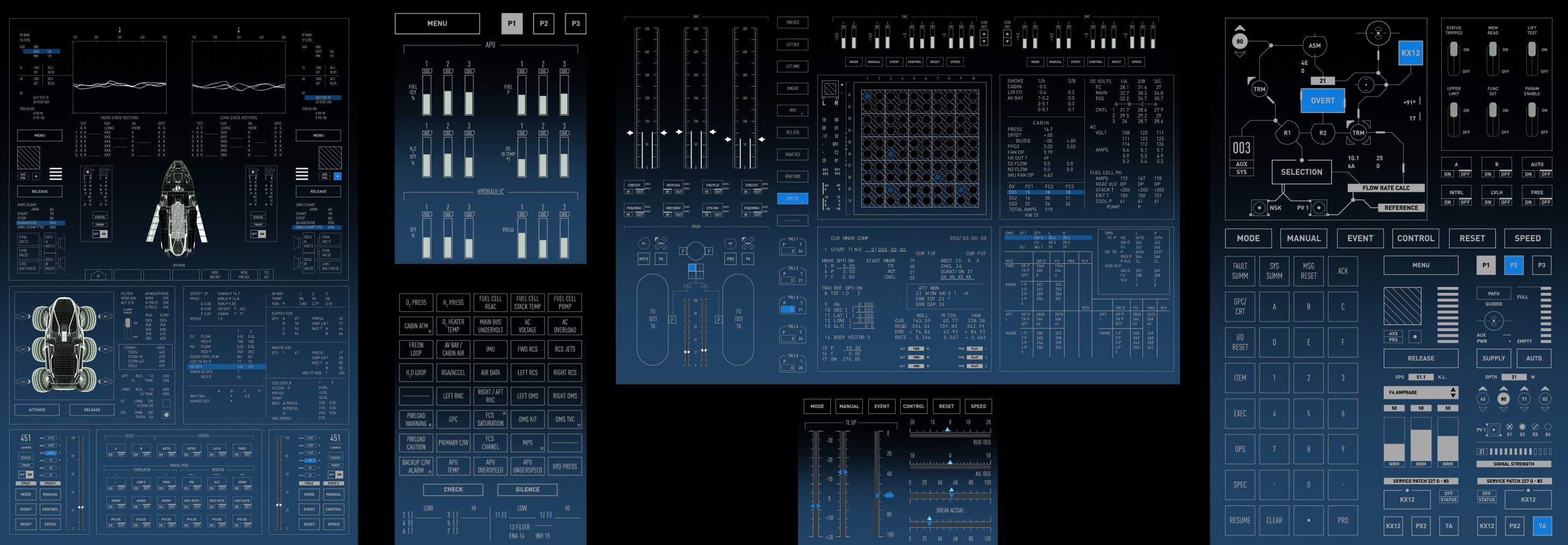

Screen graphics for “The Flash” Season 8 Episode 19, courtesy Danny Ho and Scarab Digital.

Continue reading »

Continuing the ongoing series of interviews on fantasy user interfaces, it’s my pleasure to welcome Clark Stanton. In this interview he talks about the chaotic nature of productions and how screen graphics fit into supporting the story, differences between working on set and in post production, the pace of episodic productions, and the potential place of generative AI in this creative field. In between these and more, Clark talks about his work on screen graphics for “Chicago MED”, “Free Guy”, “Moonfall”, “Tomorrow War” and “The Peripheral”.

Kirill: Please tell us about yourself and the path that took you to where you are today.

Kirill: Please tell us about yourself and the path that took you to where you are today.

Clark: Hey, I’m Clark Stanton, I’m a creative director and playback graphic supervisor at Twisted Media. I have been creating and facilitating screen graphics for a little less than 11 years. I started after school at a luxury realty company, and moved on to freelance motion design before landing my first full time job at a small production company. I started my career in film and TV after I met Derek Frederickson (who you’ve also interviewed) at a Chicago motion artist meetup where we became friends. A little later on when he got particularly busy, and convinced me to drop my other motion design job and join Twisted Media as his first full time employee. I had no idea what to expect and was incredibly lucky to fall into a dream job.

Kirill: Do you ever think how lucky we are to have been born into this digital world, and not 200 years ago where we would have to plow fields as peasants?

Clark: Absolutely. I’ve been a nerd through and through since I can remember. My brother and I started the first Starcraft club at our junior high. We were always networking computers across the house and playing with technology. We were fortunate enough to have access to some of that pretty early on in our development, and it spawned a love for computers and technology – that helped lead me to where I am in film. Honestly, I can’t even imagine doing anything else.

Kirill: As you joined the field and got a glimpse or two about how the sausage is made, if you will, do you remember being particularly surprised by how things work behind the scenes?

Clark: I always thought that every production had a plan that they were executing, these perfect machines that churned out magic. But the real nature of production is there is plan, but it’s always chaotic. You have all these individuals coming on a new group project, and everyone’s learning how to work with each other well. They’re building the plane in real time, making decisions in real time. Production might be focusing on one area or another because it’s extra complex, and our part in telling the story is usually pretty small in the grand scheme of things. So because we always have the golden parachute of going green and figuring it out later in post. We often get pushed to the edge of that creative decision making.

It’s been interesting to learn how to advocate for yourself, to make sure that the production gives you the answers you need, so that you can solve their problems and move the story along – hopefully in camera. And when that doesn’t work, then it’s always fun jumping into post and learning where the edit went and what actually needs to be there. Sometimes you have a huge elaborate graphic that you built for set, and it gets cut down. Maybe they liked the actors’ reactions, and now they’re changing the edit and trimming down or transforming what was in the original script to make the story more clear, until you’re left with just one of the original ten beats.

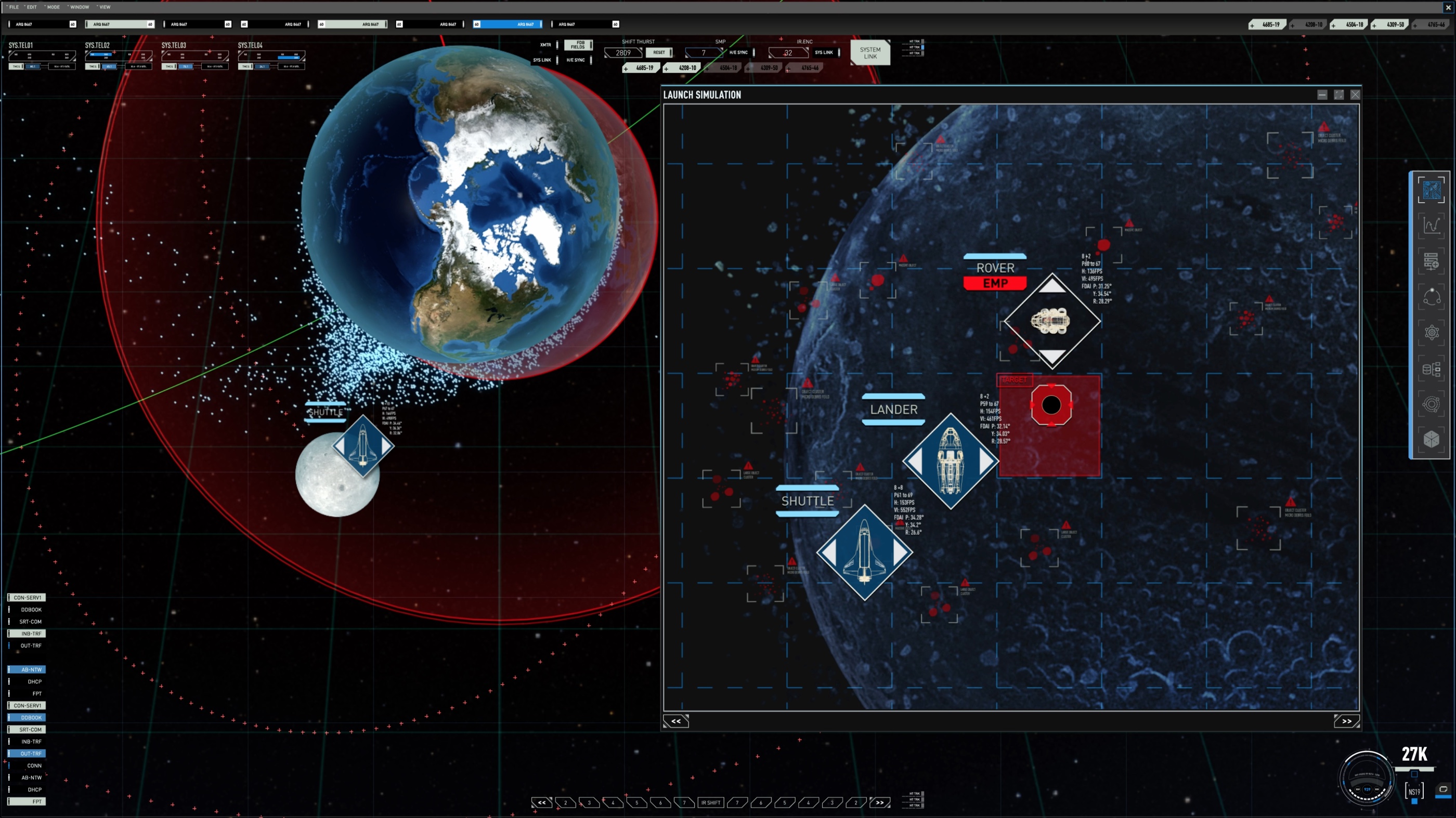

Screen graphics for the loading simulation on “Moonfall” by Clark Stanton.

Kirill: Do you have a preference to work on set versus in post?

Clark: I personally like to build the graphic for set. It’s more fun to play with the dynamic timing. You don’t know how the actor’s going to read their lines, or how much they’re going to pause or emphasize something or play up the drama. Having the reference there for them so that they can point to the screen or read the screen or react to it is much more enjoyable for me.

That said, there’s so much more freedom in post. You know where the edit’s going. You know exactly what you need to see. You usually have a little bit more time on post to get those creative answers and have the attention of the director or the producer. You can play with that part of the story a little bit more precisely.

Kirill: Is there a particular set of skills a person needs in order to not get burned out?

Clark: As a person that’s a workaholic by nature, I think that you need a hobby that isn’t in front of a screen. I’ve always played video games. I’ve always loved creating my own art. This industry has taught me that I need to stand up more and get away from my desk, and that’s my main advice to somebody that is going to try and get into this industry. Make sure that you have a good hobby that you can disconnect with. This industry is feast or famine. You have to take the jobs when they come, sometimes they overlap, and that’s a recipe for burnout.

I personally lift weights, swim or go biking. That has definitely helped me to come back fresh and creative for the next project.

Kirill: There are different names to this industry – playback design, screen graphics, fantasy user interfaces. Do you have a preference on which one best fits what you do?

Clark: Screen design or playback graphics is more how I associate. FUI comes in a lot more when you get into some of the cooler, more post fantasy projects, where you get to explore a holographic HUD in Iron Man or Spider-Man. They’re all applicable. I favor playback, so I tend to lean that way. But if you’re talking to a layman, they might only recognize FUI because of the nature of press coverage for the more recognizable projects.

Kirill: Putting on that layman’s hat, how do you tell me what your job is and why it’s needed? I have my layman’s phone in my pocket and my layman’s computer at home, and those have plenty of user interfaces already on them.

Clark: The easiest way I get it across to people is through cues. If a director wants you to start from the middle of the scene, the actors need to remember where they were, and then continue that scene from the middle. Now, if they have real phones for texting back and forth, you’re interacting with those messages. What happens when it’s a reset? Props has to run in and delete all those text messages, but also to reset the phone time because it’s been 5-10 minutes since the last take. That’s one aspect of it – replayability and manipulation.

The other part is the legal aspect. If you have a villain, Samsung or Apple probably don’t want them to have their product in there for the bad guy. Creating fake interfaces allows you to get around legal clearances.

Screen graphics for the lander cockpit on “Moonfall” by Clark Stanton.

Continue reading »

Continuing the ongoing series of interviews with creative artists working on various aspects of movie and TV productions, it is my pleasure to welcome back Tom Hammock. In this interview, he talks about the scope of blockbuster franchises, building physical sets and things that are still missing in digital worlds, traveling the world to make movies, and the rising of generative AI tools. Between all these and more, Tom dives deep into what went into making “Godzilla vs. Kong” and “Godzilla x Kong”.

Kirill: What happened to you since we spoke earlier last year?

Kirill: What happened to you since we spoke earlier last year?

Tom: Well, we made a movie called “Godzilla x Kong”, which was great. And there’s another one that I just finished with Zach Cregger who directed “Barbarian” in 2022. But really the big thing was Godzilla, and as you can imagine, it took a long time to make that movie.

Kirill: One thing I couldn’t figure out is how to say the name of the movie. Is it “together with Kong”, “against Kong”, something else…

Tom: It’s tricky to figure out. I know they tried a lot of titles, and “Godzilla x Kong” worked in the wrestling sense, in terms of them teaming up. That was always the goal. We knew we wanted to do the “versus” film and then the “team” film.

Kirill: How many previous Godzilla and Kong movies have you watched?

Tom: Adam and I watched pretty close to all of them, genuinely. When we started “Godzilla vs. Kong”, Adam had a little TV in his office, and he scoured the internet for VHS, laser discs, anything he could find. He would play them constantly, and we’d come in and reference scenes. It was an interesting process. I’d say that I’ve seen big chunks of the majority.

Kirill: Are we talking also about the 30-odd Japanese ones?

Tom: He was able to get his hands on pretty much all the Japanese films, and another seven or so King Kong variants from around the world. We put in our time. You see little Easter eggs sprinkled through. Every once in a while, there will be something.

Kirill: Did you know that there was “Godzilla Minus One” happening roughly around the same time?

Tom: We did. It’s similar to when “Godzilla vs. Kong” came out, we had a sister movie, which was “Shin Godzilla”. Toho and Warner Brothers Legendary talk a bit and plan things out, because it’s not just the films. You have the trailers, you have the toy releases, you’re trying to build the excitement. Also, Takashi Yamazaki and Adam Wingard are friends.

On the sets of “Godzilla x Kong”, courtesy of Tom Hammock.

Kirill: How was your experience going from the smaller art department on “X” and “Pearl” to this huge machine?

Tom: It’s a crazy change in scale, but in some ways it’s the same experience. You have your base camp, and you make your way through all the trailers and all the equipment. And at the end of the day, it’s still two people talking in front of a camera, which is the same as “X” and “Pearl”. But in other ways, Godzilla is so different.

On “Godzilla x Kong” we could go to literally an island to build the Monarch base on the beach. We had had the resources to do that, to get that level of in-camera work – which was fantastic and a ton of fun. Budget goes up, but expectations go up too.

Continue reading »

![]() Kirill : Please tell us about yourself and the path that took you to where you are today.

Kirill : Please tell us about yourself and the path that took you to where you are today.![]()

![]()

![]()