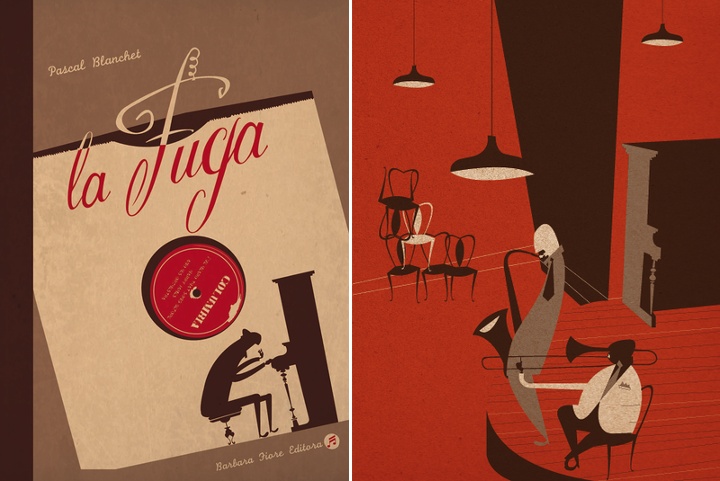

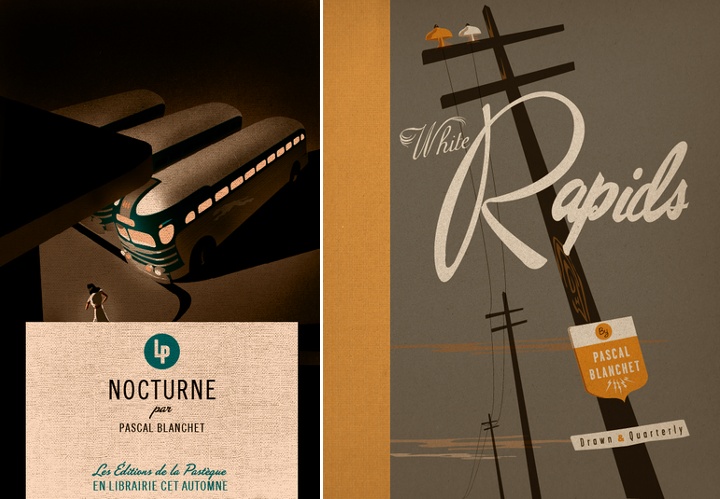

Light and shadows. Rough angles and streamlined curves. Misleadingly simple color palettes and explosively dynamic body language. Browsing the portfolio of Pascal Blanchet takes you decades back into the roaring era of Art Deco and does not let you go. I am absolutely thrilled to have the privilege to Pascal and ask him a few questions about his art and craft.

Kirill: Tell us about yourself and how you started in the field.

Kirill: Tell us about yourself and how you started in the field.

Pascal: I’m a self-taught illustrator. I’m 33, living in Trois-Rivières, a charming old small town right between Montréal and Québec city.

When in my early 20s I moved to Montréal to try finding jobs as an illustrator and I failed. It was a really rough time. I finally tried to send my portfolio to some NYC illustration reps and signed with Jacqueline Dedell agency. The first jobs came really quickly from the San Francisco magazine and Penguin Books. It was a big surprise for me!

Kirill: What drove you to be a freelancer?

Pascal: I always had a serious problem with authority. School and student jobs were a nightmare (for both the bosses and I)

so I guess it was only natural for me to end up as a freelancer.

Kirill: What informs and shapes your taste and style?

Pascal: My first contact with illustration was when I was a kid with the old 78rpm records sleeves at my grandparents house. It makes a huge impression on me.

I learned many many years later that they were made by guys like Jim Flora and Alex Steinwess and many others… I also remember having a huge crush for handlettered windowshop ads. It seems I loved art deco posters and streamline style illustrations long before knowing what those styles were. I’m still trying to find and explanation about my love for the 30s and 40s. All I know is that even when I was around 5 or 6 years old it was there.

Kirill: How has your style evolved over the years? Are you comfortable with it, are you pushing it in new directions, and do you want people to recognize your new work as uniquely yours?

Pascal: I like to think it changed a lot over the years. Looking at my first graphic novel and my last one makes me think that I’m (I hope) not too squeezed in my own “style”. It’s also really important to me to look for something else, something new (to me). I never tried to make something I could call MY style, I guess it just comes out that way. I am mostly afraid to repeat the same thing again and again.

Kirill: You cite music as your main inspiration, and some of your graphic novels incorporate artists and music instruments. How do you convey this dynamic experience in a static medium?

Pascal: I think music has shapes, colors, shadows just like a drawing. To me when I’m working on a graphic novel it’s pretty hard to know where music stops and drawing starts. Most of the time music comes first and often even gives me the subject of the story or the characters.

To me there’s no difference between music and visual arts. A jazz musician has to take a standard and recreate it in his own personal way – just the same as an illustrator. Usually the themes aren’t new at all but we have to make it our own.

Kirill: What drives you to publish graphic novels? How does it feel to hold a printed book of your own?

Pascal: I think it was the thrill to tell the story behind a single image in a more complete way. Most of the time in illustration you have to tell something in a single image and sometimes it’s a bit frustrating.

When you finally hold your book in your hands, it’s months after you finished it, so you kind of look at it with stranger eyes. The feeling you had when you were doing it is already gone and nothing much left but: This page is not good, that face looks ugly, bad shadows here…

Kirill: How do you preserve color fidelity when the final product is targeting print media, such as magazines or books?

Pascal: Pantone colors number. But I’m not that much a freak, since all the colors will change but the balance between them will stay the same. So it’s ok even if they are not exactly what I had in mind.

Kirill: As you start working on a new project, is it pen and paper first, or all-digital?

Pascal: It really depends, I do not have any kind of work routine except for music. Sometimes i make a digital sketch and the final on paper, sometimes it’s the other way.

Kirill: What’s the weirdest client feedback you ever received, if you don’t mind sharing it?

Pascal: “Can you make it more à la Pascal Blanchet”

Kirill: How do you work with type? Do you design your own fonts, or adopt and adapt existing ones?

Pascal: Most of the time I make my type. To me it seems impossible to make a poster and have a graphic designer put fonts on it. It needs to be an integral part of the illustration.

Kirill: Some of your illustrations employ high angles, claustrophobic environments, long shadows and stark silhouettes. Do I detect a fellow film noir fan?

Pascal: Totally! But the origins of the high angles and dramatic views came from my passion for architecture. I discovered film noir long after I started doing exaggerated perspectives. My father was working as a technical draftsman and I learned it at a really young age. Also, I am really fascinated with the relation between human being and architecture – how can the latter magnify or oppress the former. I guess my love for art deco also adds to the dramatic side.

Kirill: What do you think when you look at your own work from a few years ago?

Pascal: Bad work, lousy illustration, need to draw something better NOW.

Kirill: How important is it to invest time in personal projects?

Pascal: I think it’s absolutely necessary to keep myself “creative” and incorporate new techniques and make experimentations. Graphic novels are also the best portfolios you can make, my personal projects gave me most of the jobs I’ve had.

Kirill: What do you do when you run out of ideas and get stuck?

Pascal: When i have enough time in front of me I just sit and think. Drawing just makes me sink even more in the bad concepts way. When in a hurry (most of the time). I like to discuss it with the art director. Sometimes it gives a sudden new turn to the job and helps a lot.

Kirill: What’s the best thing about being an illustrator?

Pascal: Drawing and challenges.

And here I’d like to thank Pascal Blanchet for this great interview. You can find him online at his portfolio and blog.

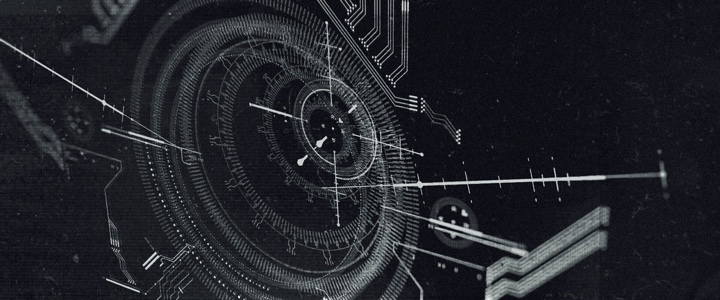

A concept artist. An illustrator. A designer. Meet Ash Thorp. In this conversation he talks about his concept work on “X-Men”, “Thor” and “Prometheus”, the user interface work he did for “Total Recall”, coming up with creative concepts and bringing his ideas to life, his thoughts on where the human-computer interaction is going and the evolving landscape of making indie sci-fi movies.

Kirill: Tell us a little bit about yourself and your work so far.

Kirill: Tell us a little bit about yourself and your work so far.

Ash: My name’s Ash Thorp and I am a designer, an illustrator, art director, creative director. I do a lot of stuff for film, multimedia and video games. I’ve been freelancing from my home studio for almost a year now, and I’ve been in the film industry for about three years. I’ve been drawing since I was a little kid. I picked design in college and got two degrees, and after that I immersed myself into the furthering my education via the internet, which lead to me discovering my own voice.

Kirill: Was it your intended goal to get to work on movies?

Ash: I grew up on a really healthy dose of Saturday morning cartoons and anime and film, and I feel that film is a great medium of storytelling. It was always a big goal of mine to do something in film on way or another. It was always in the back of my head that I wanted to do it, and even though I didn’t know how I would do it, I figured out I’d make it happen.

I was working at a design firm down in San Diego doing graphics for action sports. It was fun, but I felt that I wanted to do something greater for myself, on a higher level, for more mass appeal if you will. I decided I wanted to design for film, and I had to figure out the niche I wanted to be in. I started following a few companies doing motion graphics. I suppose I was OK at design at the time – nowhere near where I am now, and there’s always place to grow anyways – and I saw that it was the niche for me. So I gave myself a time limit of three months to build a portfolio. Every time my wife and my daughter would go to bed around 11PM, I’d work until about 4AM on just building the portfolio, making a bunch of projects, which lead to creating the web site with much material.

I put this portfolio together, and I sent it out to around 50 studios. I got contacted back by only one of them directly, and it was Prologue, I was extremely surprised because they were my favorite company. I went there to interview, and they offered me the position of a junior designer. There was a little bit of negotiating, and a lot of talking with my wife. We live in San Diego and Prologue’s office is in Marina Del Rey up in LA. It’s about 2.5-hour drive, so I had to figure out a system to make it work, commuting every day for a whole year, building my skills and getting better at it. It was pretty crazy, commuting six to seven hours every day to work.

Prologue works on tons of films, and there was a lot of opportunity to grow. The artists and creatives there are just amazing, and it was really great to understand what it takes to do design at that level. It was like bootcamp. It was the hardest thing I ever had to do in my life – the endurance of the whole year, not being able to see my family and friends that much, being completely exhausted and drained, working really hard. Prologue is a very intense environment, great for building yourself but really taxing, with extremely rigid timelines. You gotta do a lot of productions and a lot of work. It was good, and that’s how it all worked out. I left after a year, helped out a friend for about six months, and then started working on my own things from my home as a freelance artist for hire.

Kirill: Were you surprised during that first year, working on real-life productions across multiple departments?

Ash: I learned something new every day, a new surprise every day. You know, when you learn a magic trick, it takes the magic out of it, but it’s still really interesting. I feel that the deeper I go into film and understand it, the further I go from the original thing that I loved about it – which is the innocence of being a fan, now that I understand how the things are made.

Kirill: What were the specific productions you worked on at Prologue, and what was your role?

Ash: Some of the movie projects I worked on there were X-Men First class, Thor, then Walking Dead which became concept pitches to the director. Design houses like Prologue compete in this over saturated market where the client requests to see the design vision for a certain production – usually for free, which is pretty crazy. Those were my original concepts and ideas for things that I worked on with a group of people. Each project would change or shift depending on the notes and feedback from the clients and things would move along from then on taking on a life of its own.

Continue reading »

Continuing the ongoing series of interviews with illustrators, today I’m pleased to welcome Natalie Smith on my blog. Natalie’s portfolio is a charming collection with particular emphasis on delightfully quirky character illustration. She also designs T-shirts, and selected illustrations are available for sale over at Society6. Natalie’s Dribbble page, DeviantART gallery and Tumblr stream are full of sketches and work-in-progress snippets that provide a fascinating glimpse into her creative flow.

Kirill: Tell us a little bit about yourself and how you got started in the field.

Kirill: Tell us a little bit about yourself and how you got started in the field.

Natalie: I am a self-taught, freelance illustrator born and based in Yorkshire, England. Although I’ve always enjoyed drawing, I kind of fell into illustration a few years ago after winning a couple of t-shirt design competitions and through people taking notice of my personal work on Web sites such as DeviantART and Dribbble.

Kirill: Is it important to evolve your stylistic choices? Is there ever a thought of exploring radically different directions? Is there a concern of falling into a certain rigidity of style?

Natalie: I’m not sure if it’s about evolving my stylistic choices per se, but I do think it’s important to experiment and try out new ways of approaching an illustration in order to progress. In fact, it’s more a case of “what can I do to make my work better”? For me it doesn’t even have to be anything too drastic either; it could be something as simple as using a different brush in Photoshop, for example.

As for style, I think it’s ultimately just an amalgamation of what interests you at a given time. As you go through life these interests naturally change and evolve and with it so does your style.

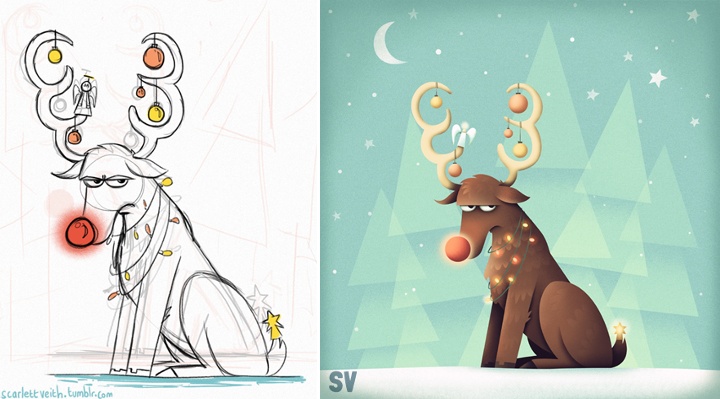

Kirill: From pencil sketches, to the initial transfer to the digital mode, to circling on finer details – what’s your favorite phase?

Natalie: It really depends on the project but generally speaking sketching is my favourite, as that’s the most creative phase of the process and the part where you still have the freedom to do anything. Then it would probably be adding the finer details.

The most tedious part of my process, due to how I work and produce my illustrations, would be laying out the paths and the base colours for my piece.

Kirill: When you transfer your pencil sketches to the digital world, do you try to preserve some amount of hand-drawn imperfection? Is this important to you?

Natalie: I actually do a lot of sketching straight in to Photoshop these days, but when I do use my sketchbook it’s nearly always to put down and explore ideas, crank out thumbnails and try out different compositions and layouts. So my pencil sketches are really just a foundation to build upon rather than a piece of the finished illustration. Sometimes I will do individual bits of the illustration and then piece them together once I’m on my computer.

That being said, I have been trying to incorporate more of a “roughness” to my work, which I think adds a little more character. For this reason I also tend to create a lot of textures, which I use in my work, from traditional sources such as different types of paper and scanning in brush marks.

Above all though, it really depends on what is needed and what will best help communicate the message of the illustration.

Kirill: What do you like about character design and why?

Natalie: I’m not sure exactly what it is, but the first thing I really remember properly sitting down and drawing lots of were the characters from The Simpsons – so I think it’s just something I’ve always been interested in.

Kirill: What’s different about designing t-shirts? Which parts translate well to the wearable medium, and which do not?

Natalie: The biggest thing you have to remember is that a design someone may hang on their wall isn’t necessarily what they would want to wear! But the way I approach designing a t-shirt is largely similar to how I would tackle other illustrative work; composition, colour etc are just as important.

However, there are certain things I do take into consideration when specifically creating a design for t-shirts. For example, where the design is placed on the t-shirt is important – either to give the design more impact or to avoid it from being unflattering. From my own experience, I also tend to find that simpler designs tend to do better (though this may not be the case for others).

Kirill: Do you think that advances in software tools and global connectivity are making it simpler to start in your field, and at the same time creating more competition and diversity for the clients to choose from? Does it make harder to stand out?

Natalie: Not so much advances in software, as I believe it will only take you so far, but definitely having access to sites like Dribbble, which broadcast your work on a global scale, has made it easier for me to get started in the field. At the same time I do think it creates more competition, but I believe that if you have the passion to progress and the talent then you will always, in the end, stand out.

As a side note on this subject, because I’m self-taught the ease at which you can now have access to other artist’s work and be able to communicate with them and learn from them has been a huge boon for me.

Kirill: How valuable is self-initiated work for you?

Natalie: Extremely! First of all, it’s a time when you can really play around and experiment with your illustrations. It also creates a consistent output and allows you to refine your process and become more efficient at what you do.

Kirill: What’s the best thing about being an illustrator?

Natalie: The variety of the work and having a great excuse to watch cartoons (it’s for research purposes, obviously).

And here I’d like to thank Natalie Smith for answering a few questions I had about her art and craft. You can find Natalie online at her portfolio and buy selected prints in her shop. She can also be found at Dribbble, DeviantART, Tumblr and Twitter.

Continuing the ongoing series of interviews with illustrators, today I’m pleased to welcome Owen Davey on my blog. Owen is a prolific illustrator whose work spans editorial print illustration, animation, book cover art, branding and more. And if that is not enough, later this year we’re going to see his third published book, “Laika the Astronaut” (which is already available for pre-order).

Kirill: Tell us a little bit about yourself and how you got started in the field.

Owen: I’ve been working as a Freelance Illustrator for about 4 years, since graduating from University College Falmouth with a First Class BA(Hons) in Illustration. My first professional commission was for the Guardian Weekend, a week before I graduated. An ex student of Falmouth was an art director for them and liked my work, so thought he’d give me a chance. Since then, it’s just snowballed really. I’ve now worked with a range of clients across the globe including Orange, Microsoft, Persil, New York Times, Templar Publishing, Walker Books, Creative Review, Jamie Oliver & Threadless.

Kirill: Your style is rooted in the mid-century period. What attracts you there, and what are your thoughts on bringing that almost analogue look back to life with the modern digital tools at your disposal?

Owen: I discovered a while ago, that my work thrives under constraints. Limiting colour palettes or applying strict compositions just seems to make my work better. That’s what I love about mid-century design. The creativity and strength of design many illustrators managed to accomplish, within the limitations of technology, just inspires me. It is certainly my golden age for design.

In terms of the analogue and digital, that’s something I struggle with constantly in my work. I love the imperfections of image-making, and the evidence of human touch, and yet I also love clean, slick and precise imagery too. I always start with drawing, work digitally, and end with textures and manufactured imperfections; that way I sort of try and get the best of both worlds. I think I’ll just always be sitting on the fence though really.

Left – illustration for “The Feed” project for Orange. Right – illustration for an article about eReader devices.

Kirill: Do you want people to recognize your work the first time they see your new illustrations? Is there a concern of falling into a certain rigidity of style?

Owen: I’d like illustrators and designers to recognize my work, yeah. I discovered a long time ago, that the general public just doesn’t have the eye for it. Family & friends always tell me when they see something they think is mine, when it looks nothing alike. I don’t mind though; it’s my job to know the difference. I never fear falling into a rigidity of style, because I’m never 100 per cent happy with any of the work I do. I’m constantly evolving my work in an attempt to improve and hone. If you look through my blog for example, there’s quite a distinct change from the beginning to the most recent. I live in a world of illustrative evolution.

Kirill: What do you think about making illustrations for web sites? How does the evolution of responsive web design and scaling the design with device size affects that?

Owen: It doesn’t bother me at all really. It’s lovely to see work in the physical world, but I love computers. They are incredibly enabling objects. I’d have sucked at living in any other era. I just love the internet too much. And the joy of work existing in the digital ether, is that you can be 100 per cent sure how the colours are going to look on your screen. Reproduction can be a nightmare!

Just to clarify though, I’m a great lover of objects of art. My bookshelf is my pride & joy. But what everybody has to understand, is that we are now living in an age, when you should only print something if it’s worth it. You either make beautifully crafted objects, or you just do it digitally. The age of the crappy plastic CD has died out but stunning Gatefold Vinyl lives on. eBooks pick up the trashy novel, while art books are printed with spot colour matt stock perfection.

Various branding materials for the Alone Aboard the Ark project.

Kirill: What does it take to create a complete branding for a new music album (“Alone Aboard the Ark”), from album sleeves to booklets to t-shirts to beer labels, all the while maintaining a unified theme across the different physical characteristics? How long did that process take, and what was the most unexpected thing that happened there?

Owen: Well the surprising thing with it, was how long it trailed on for. I completed the cover artwork before Christmas, and I’m still doing little bits and pieces for it here and there. I approached the merchandising etc. in a very self referential way really. I tried to reuse elements as much as I could, simplifying and rearranging, colour picking, dragging and dropping etc etc. It was great fun to do. Each design takes on a slightly new life, and you really get to explore an image and a theme. I hope to do it more.

Kirill: You also did the jacket design for “Wild Boy” novel. How is that field adapting to the world of digital book stores, and what effect are those scaled-down interfaces having on the process of designing book covers?

Owen: Um. I don’t really know. I don’t see much difference in designing for the digital and physical to be honest. They’re both viewed in similar ways. If it’s eye catching online, it should be eye-catching in store.

Kirill: And if we’re talking about books, you are working on your third picture book, “Laika the Astronaut” – due out later this year. How’s the world of physical publishing treating you? Which parts of the long process of publishing a book work well for you, and which parts are still rooted in the pre-digital world?

Owen: Nope. Not working on it. It’s been done for several months. Just takes ages for it to be released. Um.

Well I love picture books. The longer printing side etc. is slightly infuriating, but the creation of them is great fun. I’m used to working to tight deadlines and single images most of the time, so to be able to approach a 32 page picture book over the space of a few months is really refreshing. You get to develop ideas in such exciting ways. You can add extra concepts or fun elements, properly explore pace and flow, hone storytelling, and refine composition. Love it. And Templar are particularly good at letting me choose papers and fonts etc, so that the finished object is one I can be really proud of. I can’t wait to see Laika in the flesh!

One of the illustrations for Laika the Astronaut picture book.

Kirill: Going back to the client work, do you prefer getting a full artistic freedom for a project, or a more defined direction from the client?

Owen: It depends really. The main issues stem from a client not being sure about which they want. If they tell you you have artistic freedom and then essentially steer you to where they originally wanted you, that’s pretty annoying. But in general I’m game for both. I do like to have some input in the conceptual process, even if they give me a strong theme or specific subject matter. I don’t really love being a human paintbrush (but then sometimes that’s where the best money is)

Kirill: Does it ever happen that a client contacts you based on your existing work, but then starts pushing you into a direction you’re not comfortable with?

Owen: Not exactly. I quite like exploring outside my comfort zone, so its fun when they get me to do stuff slightly different. I’ve had clients with just simple bad taste, asking me to add horrific colours or making bad edits to images after I’ve created them etc. That’s annoying, but I dunno. I’m fairly easy going with it all. If I was too precious with my work, I’d have been a Fine Artist, or gallery illustrator. When people commission me, they have to get what they want; otherwise I’m failing at my job.

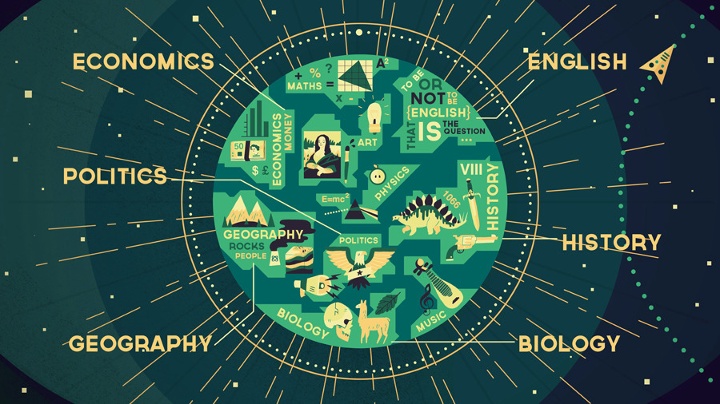

Animation still from the Wisdomap Schools project.

Kirill: How valuable is self-initiated work for you?

Owen: It’s not valuable per se. It’s just fun. There’s a massive back catalogue of work I want to get done, but I often try and slip it into commissioned work, or books. I don’t usually class my picture books as self-initiated, because there’s still a client, but I suppose it fulfills the same purpose for me; it’s a way of cutting loose and exploring my own ideas.

Kirill: And on a related note, do you ever get to take a break as a free-lance illustrator?

Owen: Nope. It’s all I think about most of the time. I do other creative things, and live my life, but it all leads back into illustration in the end. I take time off, but I usually illustrate in it anyway. My last 3 holidays have all had mini commissions happening throughout them, but they paid for the holidays, so yay to me!

Kirill: What’s the best thing about being an illustrator?

Owen: Being paid to do what I love.

Animation still from the Wisdomap Medicine project.

And here I’d like to thank Owen Davey for taking time to answer my questions. You can find Owen online on his site, his blog and Twitter. Selected prints are available for sale over at Big Cartel.

![]() Kirill: Tell us about yourself and how you started in the field.

Kirill: Tell us about yourself and how you started in the field.![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()