Mark passed away in June 2024. As domain registration for his portfolio site expired, I am hosting the reconstructed version of it on my site at this location. You’ve single-handedly created this whole field out of thin air. It all stands on your giant shoulders. Enormous talent, quick wit, and an unmatched personality. We will all miss you, Mark.

Continuing the ongoing series of interviews on fantasy user interfaces, it’s my honor to welcome Mark Coleran. His seminal work defined computer screens in film in early 2000s, influencing a whole generation of artists that do screen graphics and motion design, and he’s widely credited with coining the term FUI itself. In this interview Mark talks about the early days of doing interface design for film, his transition to the world of real-life software, application of VR and its potential future for storytelling, the difference between art and design, the slow pace of evolution of the software tools at his disposal, and how to not get burned out after a couple of decades in the design industry.

Kirill: Please tell us about yourself, and your path to where you are today.

Kirill: Please tell us about yourself, and your path to where you are today.

Mark: I’m Mark Coleran, and I usually call myself a designer. To me being a designer means to cross a broad range of things, but I would say I am mostly in the field of communication design. Communication design is about telling people something. It’s about communicating an idea, a principle, a policy.

Back in the late ’80s I worked as a graphic designer in quick print shops, large print places and agencies, and I always had a penchant for the more technical side of things. I was fascinated by tools and their potential. I’ve been using Photoshop from version one, and started using AfterEffects early on. Video production was always there in the mix of things, and my first motion graphics piece was to do a quasi stop motion animation of a logo, all done on tape-to-tape, loading them one frame at a time onto a cassette.

As I was playing with motion graphics, I almost bankrupted myself buying machines and software things like Electric Image and After Effects which had just changed owners from Aldus to Adobe, originally Cosa. It was quite limited at the time, essentially Photoshop that could do multiple frames, and it was fantastic. I was playing with these bits and pieces, and as the market was evolving, it felt to me that I was perfectly positioned as an individual designer and production artist. It is production art because you are doing things for other people.

It was a good place to be, and it opened up certain opportunities. I worked with a prosthetics company in Pinewood that was doing a digital back end to the prosthetics people to extend that prosthesis out. So somebody might build a smaller part of a dinosaur as a prosthesis, and we would build the rest of the dinosaur digitally. I wasn’t too much into character animation, but it gave me an opportunity to work on a wide range of things like 3D modeling and compositing. While I was there I collaborated with special effects companies that were working on rendered wireframe sequences like a jump stunt off the top of a building. You add a lot of detail into that image to essentially reproduce what the stunt would be like in a cut, and that keeps the insurance people and the director happy and calms nerves as it gives a clearer idea of the “real” shot.

I always loved techy graphics, especially in movies like “Dr Strangelove” and “2001: A Space Odyssey”. The graphics there are geometric and mechanical, and they work to tell a story. So it just happened to be that on “Entrapment” they needed a screen to show how long this rope was, and I asked them if I could work on that screen. There was another company already working on it, and I ended up doing some visual effects and compositing on this little handheld computer. That was a good experience, and it got me in the door to work with Useful Companies, specialized in display work and screen graphics.

That would later be coined FUI, and I’m not sure I can take credit for that name, even though I’m given credit for it. Nobody knew what to call it and I was not quite happy with that name, but sadly it worked. Nobody outside of our little industry knows what that actually means, so maybe it’s a half success.

From there I learned a lot about doing screen graphics and got to work on some really good projects. It also came with the realization that I was a terrible designer. I don’t have any background or training for it specifically, but I do have a background in engineering drawing. I used to work with large, complex documents, and I started bringing that aesthetic and precision into my work on screen graphics. There two things married up quite well and worked for me rather than against me. I got to work with great people like Simon Staines. He’s a phenomenal designer, probably one of the best that you’ve never heard of as he prefers to keep his head way below the parapet.

People give me a lot of credit for this field, and a lot of it goes to him. I’m good because he’s good. He taught me a lot and turned me into a proper designer. He deserves a lot of credit in our field.

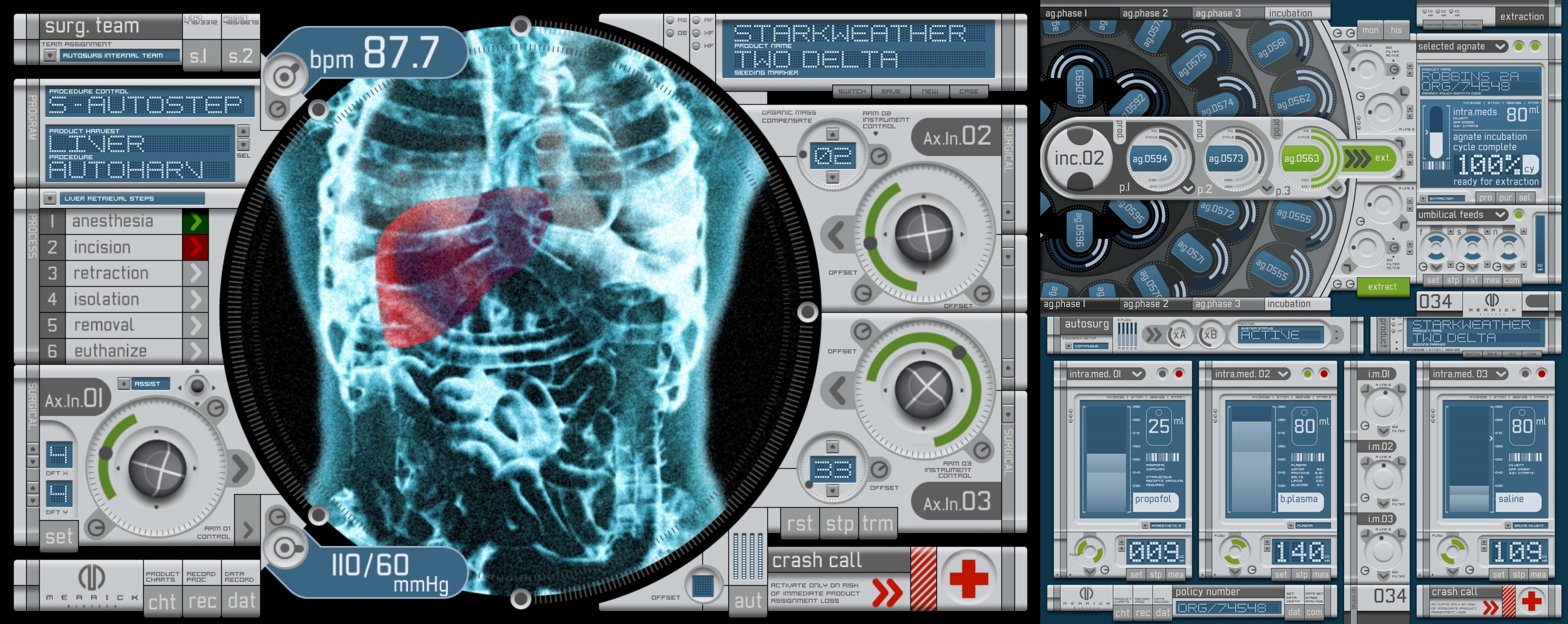

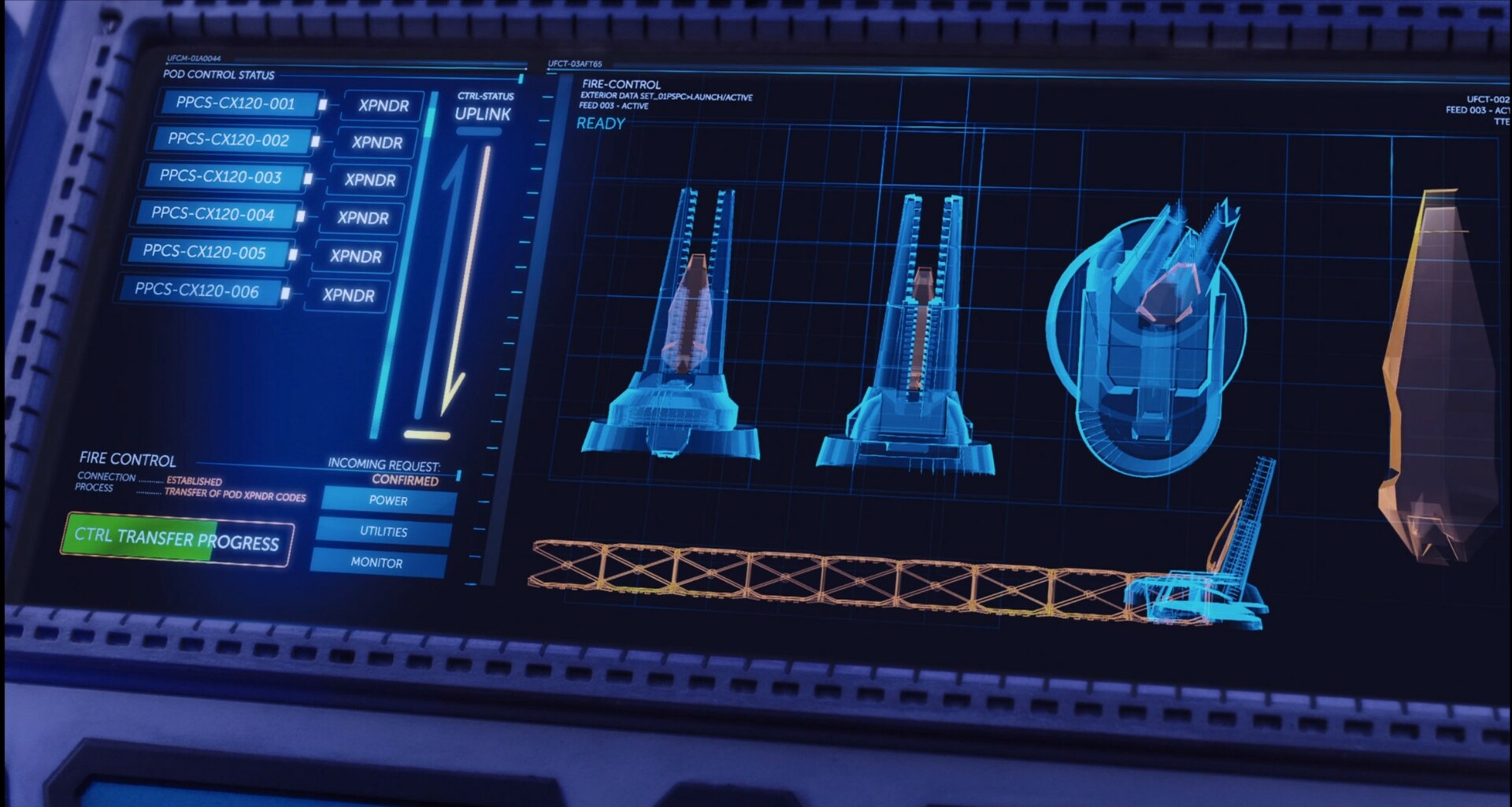

Screen graphics for “The Island”, 2005, courtesy of Mark Coleran.

Kirill: And then around 2007 you stepped away from the “fantasy” world into the “real” world projects.

Mark: That is true, but not quite as clear-cut. I love the software people create. You use it and you use it for a long time, and as they say, familiarity breeds contempt. And it’s absolutely not contempt for the people, believe me. People who make this software are amazing and talented, but you get frustrated with the limits of the software itself. You reach out, you talk to people, you find that sometimes those limits can’t be changed and sometimes they can. I got a chance to work with a lot of different people and contribute towards some of that as well. It was gradual, as it goes back and forth. I also had people reaching out to me asking to work on the interface part of their software.

All of this combined led to quite a few years of doing UI work, and that work is not as simple as people think. There’s a lot of factors involved in that. You have the technical capabilities of software and the systems they are running on. You have the user experience and the interaction part of it, which is massive. It took me a long time to learn this new craft and its considerations, going through the same process as I did with screen graphics. I had a couple of full-time jobs, and then joining GridIron who were known for their Nuclear Pro software.

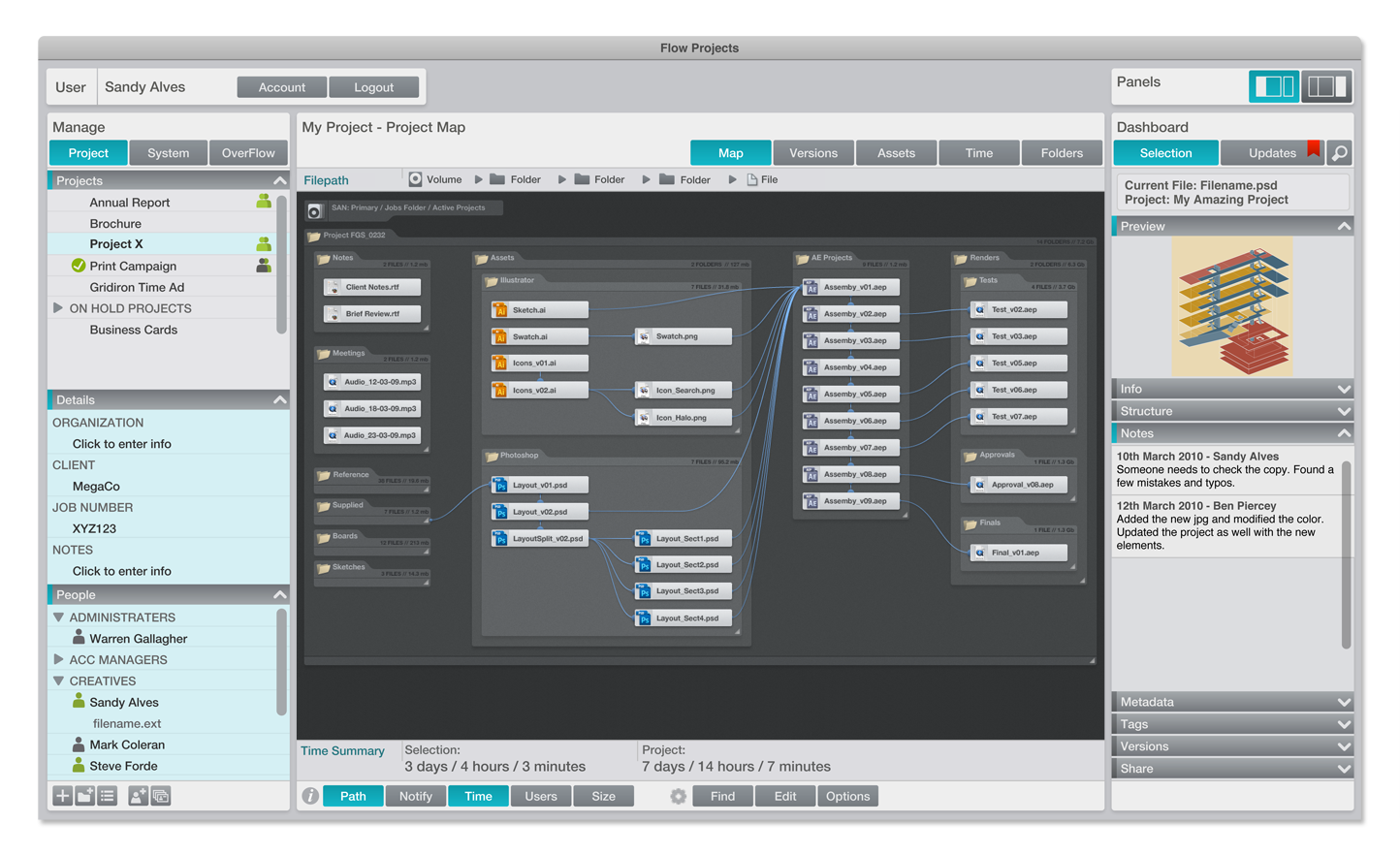

We had discussions about some new ideas, and I joined them to contribute to the creation of a piece of software called Flow. It was designed specifically for artists like myself, and the idea was to try to improve how we do things. It was a great lesson and a great experience. I worked with phenomenally smart and brilliant people. It was a brilliant product and everybody loved it, but nobody bought it [laughs]. It was a lesson in so many aspects. It was an interesting experience to try to tie the film fantasy type of work to real products, because people love that aesthetic.

GridIron’s Flow, courtesy of Mark Coleran.

I recently did a conference talk with RGD in Canada, and it was about taking away the wrong lessons from FUI. I talked about the work I’ve done in films, and how I tried to apply it to the real world, and how I tried to apply the wrong things. We tend to fall in love with the aesthetic, and we think that the good looks are what makes it work. But the work we do in film is to create a diegetic prop. In film, you need to create a feeling about the person using it or the scene that it is in, or to articulate something about a piece of action or other plots.

It’s an illustration and a storytelling device, and there’s not much more to it. I say this not to dismiss it, as it is a really important thing. But it is not an interface. It was not designed to be used.

We spend so much time in film to make things look sophisticated and complex. It is sometimes horrendous how much time we put into the amount of detail we put into interfaces, and that is needed to impart a feeling of what it is supposed to be. And yet, real world software goes the opposite way of that. You try to make it less detailed, simpler, focused on the task that needs to be completed – and those things don’t work together. The film aesthetic fails here, in a sense.

But there are so many ways we can use the stuff from film. In film, you are telling a story, and in a sense, this part is quite under-utilized in real life software. When I work on interfaces for film, I use the same principles of composition as it’s used on the wider scene. I use light, shape, form, movement and sound to draw people’s attention to the right place. Each film screen has to have what we call a read. I see this thing, I have to understand it, and it has to tell the viewer exactly what is happening. And it has to happen instantly.

But I didn’t initially take these lessons back to the real world. It took time. It is not about the aesthetics. It is about how these cinematographic principles could make software better. The cinematic interface is not necessarily about how it looks like, but rather how it feels like. Adding animation to interfaces was one innovation that started in film. I was teaching it to myself, based on the same principles. Where am I? How did I get here? What can I do? Where can I go? Animation can assist with answering these questions. It was a great lesson on what to do and what not to do.

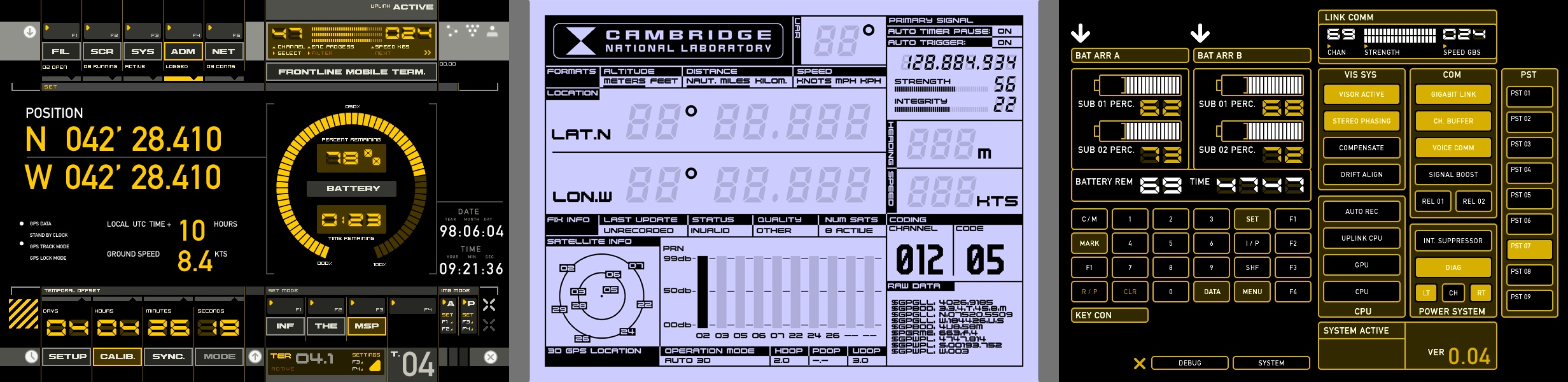

Screen graphics for “Deja Vu”, 2006, courtesy of Mark Coleran.

Continue reading »

Continuing the ongoing series of interviews with creative artists working on various aspects of movie and TV productions, it is my pleasure to welcome Cynthia O’Rourke. In this interview she talks about the often-invisible art and craft of makeup, the evolution of it in the world of high-definition productions, the role of storytelling in our lives, and the impact of the ongoing pandemic on her industry. Around these topics and more, Cynthia dives deep into her work on “A Mouthful of Air”.

Kirill: Please tell us about yourself and the path that took you to where you are today.

Kirill: Please tell us about yourself and the path that took you to where you are today.

Cynthia: As a kid I always loved movies and storytelling. But as I got older, I started wondering how they did certain things. When you’re a little kid and you’re watching a horror movie, you’re so wrapped up in it and you’re not thinking about the technique behind it, because you’re thinking it’s real. But as you get older and more mature, you understand that that person didn’t really just have their leg chopped off or whatever. But how did they fake it? I was so fascinated by that question

I had a part-time job in middle school making $20 a week. I’d take that money, I’d go to the video store and I’d rent a movie for myself for the weekend. I have four siblings, so being able to pick a movie that was my choice and nobody else’s was this special little treat I gave myself. I started watching silent movies with Charlie Chaplin, and old classics as well as the new releases. I remember “Braveheart” having a big impact on me. I’d fast forward and rewind and watch these big battle scenes to understand the illusion of these people dying when I know they didn’t die.

Around high school I was trying to figure out what I wanted to do with the rest of my life for college. I was really good at science so I was thinking pre-med or I was going to apply to film school – so I made a deal with myself that if I got into film school, I would do that. I ended up going to Tisch School Of The Arts at NYU for film and television, and that was my undergrad. There, I fell even more in love with film because now I was learning all about behind the scenes, how to do it. I was fascinated with the storytelling element of editing, and when I graduated, that’s the direction I took. This was right after 9/11 and in the middle of a recession. A lot of the post-production work that was happening in NYC had left so there weren’t many great job opportunities or places to work your way up into the craft. I ended up becoming disenchanted with post and I started looking for other avenues that I could pursue while still staying in film & TV.

One of the things that I loved in college was the special makeup effects class I took. So I took a leap and left my assistant editing job. I went to makeup school, did a course for character, beauty makeup and special effects, and started freelancing until I got into IATSE Local 798 – the union for makeup artists on the East Coast. That’s my origin story!

Kirill: Do you feel sometimes, and maybe it is more pronounced in the US, that we expect young adults to know what they want to do for the rest of their lives when they just graduated from high school?

Cynthia: I know I felt that way when I was a senior in high school. Now as an adult, with kids of my own, I know that you can be interested and pursue many different things. You don’t have to be locked in. But there’s this expectation on kids: “You’re going to decide what you want to do, you’re going to go to college, you’re going to get on that path, you’re going to keep on that path and then eventually one day you’ll retire”. It’s an illusion. It’s not real. But I know I felt it as a kid, all this pressure to make up my mind right now, and to know and decide.

Kirill: Looking back at your first few productions, as you were seeing all the behind-the-scenes tricks of how “movie magic” is made, did it diminish in any way your enjoyment of watching a story unfold before your eyes when you go to a movie theater?

Cynthia: I have a hard time watching projects that I’ve worked on, because I’m thinking of being on set and what happened that day. But if I’m watching someone else’s work , usually I can suspend my disbelief. I’m a makeup artist, and sometimes if there’s something really distracting about the makeup, it can take me out of the story. But usually, as long as it’s not something I’ve worked, I can get into it and get enveloped in the story.

Kirill: If you look back at the last 15 years, do you find that you are expected to do more? Our screens are getting bigger in size, and have higher resolution, and perhaps that is raising the expectations from every department.

Cynthia: As a makeup artist, it’s not necessarily that we’re doing more for HD. Sometimes we’re doing less. When you have lower resolution and smaller screens, contrast is more important and you’re able to do optical illusions in a way to change shape and textures.

When you’re working in HD, your approach has to be quite different. I don’t want to say it’s less work, because actually I think it’s more work. You have to be really subtle. Think about painting: You can throw on the oil paint, and it’s thick and textured, and up close it’s a bit of a mess. But step back and you have Monet’s Water Lilies. Or you can have a watercolor painting where the texture is so subtle and the surface is completely flat but the image looks real enough to touch. Working in HD is a little bit more like doing the watercolor part of it and it takes a lot of work to achieve that. You have to really be subtle about it.And because the makeup is so subtle, there’s this mistaken idea that we haven’t done much to that actor’s face [laughs]. People don’t really understand or see what it is we’ve done, because it’s so subtle. That’s something that comes up a little bit. Even our colleagues in other departments might have no idea what went into making that person look completely flawless.

Kirill: Does that make your blood boil a little bit to hear people say that it’s a “natural” look without realizing how much work might go into that?

Cynthia: When I was younger, my blood would boil, but now it rolls off my back. There are people in the business who know better, and those are the people I like to work with – the ones who appreciate what the Makeup department brings to the table.

There’s so many different people and departments who work on a film and make it happen. We’re all collaborating, we’re all adding something. The Makeup department is not there for no reason. We’re there for a reason, and we have our own little part to contribute to the whole thing.

Continue reading »

Continuing the ongoing series of interviews with creative artists working on various aspects of movie and TV productions, it is my pleasure to welcome Chris A. Peterson. In this interview he talks about the transition of the industry from film to digital, the role of an editor in bringing stories to our screens, and what stays with him after productions wrap up. Around these topics and more, Chris dives deep into his work on “American Crime Story: Impeachment”.

Kirill: Please tell us about yourself and your path to where you are today.

Kirill: Please tell us about yourself and your path to where you are today.

Chris: My dad was a huge movie buff. He was a big Stanley Kubrick fan, so I saw every Kubrick film at least ten times as a kid, including “A Clockwork Orange” where he fast forwarded through the really brutal parts. I gained my love of film through Kubrick and Spielberg.

When I was a senior in high school, I took a film video class as an elective. Every class the teacher would show a movie, and I thought most of them were great, but it wasn’t until we watched “The Graduate” and saw the scale of artistry in that film that I was totally hooked. I said this is what I want to do. At that point I had already applied to colleges, and I changed my major right then to film.

During that same film and video class in high school, we had to put a couple short little films together. We had to shoot in them, act in them, do everything – and I loved the editing process the most. I thought the production part of it felt chaotic but I loved the amount of control that I had in the editing. It’s a quiet room and I felt like I could think more. And later on in college, as we were doing all these different parts – directing, shooting, writing, acting – I always felt like I came back to editing. It was a place I felt comfortable in, a place where my creative strengths were.

Kirill: How different was it back then when you were starting out if you look at the tools at your disposal from then to now?

Chris: I was filming on videotape in high school in the early ’90s, and then editing on videotape as well. Then it started the same in college, and towards the end of undergraduate we got into shooting 16mm film and cutting on flatbeds. My college was not well funded in that department, so we didn’t have any computer editing systems.

It wasn’t until I graduated that I had my first experience working on a computer based non-linear editing system. My first job after graduating college was on a documentary. When the director asked if I ever used a Media 100 (an old non-linear computer editing system) I completely lied [laughs] and said I knew how to use it. So he left me there with the computer and I found the how-to book under the desk.

Kirill: So that was before the age of Youtube?

Chris: That was in the mid-’90s — way before YouTube. Flipping through the book I learned how to edit on a computer in about 30 minutes, mostly because I was scared of losing my job [laughs].

I liked editing tape to tape and cutting on a flatbed but once I got to cut on a computer, it completely changed the world for me.

Kirill: Do you think there’s any advantage for people who did come up during that time of transition from film to digital, or might some be holding on to those memories for more nostalgic notions of how it felt to hold a strip of film in your hands?

Chris: For me, having had worked on a 16mm film flatbed was transformative, and I think it still has an effect on how I edit to this day.

A lot of times, a cut you were doing on a flatbed would take at least 10 minutes, and if you were cutting multiple tracks of audio, it could get much more complicated. So every time you were going to do a cut, you really had to think about what you were doing. Every time you look at a 16mm film strip, you see that every shot up is made up of a bunch of individual frames, and that frames have value.

In non-linear editing these days you can do and undo everything in seconds. You gain speed but one of the issues is sometimes forgetting how important each frame is — two frames this way or two frames that way, what difference does it make? It matters.

If I were taking a film editing class, I would make everyone start out on a flatbed, just to understand the importance of a frame.

Continue reading »

Continuing the ongoing series of interviews on fantasy user interfaces, it’s my pleasure to welcome Rhys Yorke. In this interview he talks about concept design, keeping up with advances in consumer technology and viewers’ expectations, breaking away from the traditional rectangles of pixels, the state of design software tools at his disposal, and his take on the role of technology in our daily lives. In between these and more, Rhys talks about his work on screen graphics for “The Expanse”, its warring factions and the opportunities he had to work on a variety of interfaces for different ships.

Kirill: Please tell us about yourself and the path that took you to where you are today.

Kirill: Please tell us about yourself and the path that took you to where you are today.

Rhys: My background is pretty varied. I was in the military, I’ve worked as a computer technician, I’ve worked as a programmer, I’ve worked as a comic book artist, I’ve worked in video games, I’ve done front end web development, I’ve done design for web and mobile, I’ve worked in animation, and now film and TV.

It’s been a long winding road, and I find it interesting. I continue to draw on a lot of those varied experiences in video games and comic books, but also from the military as I’ve worked on “G.I. Joe” and now “The Expanse” when we’re doing large ship battles. It’s an interesting, and it’s a bit weird to think of how I got where I am now. It wasn’t something necessarily planned, but I just adapted to the times.

Kirill: Do you think that our generation was lucky enough to have this opportunity to experience the beginning of the digital age, to have access to these digital tools that were not available before? I don’t even know what I’d be doing if I was born 300 years ago.

Rhys: My first computer was Commodore 64. My dad brought that home when I was eight years old. He handed me the manual and walked away, and I hooked it up and started typing the programs in Basic. Certainly it’s not like today when my son started using an iPhone when he was two and could figure it out, but at the same time it’s not something that we shied away from.

I feel like we probably are unique in that we’ve had the opportunity to see what interfacing with machines and devices were like prior to the digital age, as well as deep into the digital age where we currently are. You look at rotary phones and even television sets, and how vastly different is the way we interact with them. We’ve been fortunate enough to see how that’s evolved. It does put us in a unique situation.

Screen graphics of the Agatha King, “The Expanse”, by Rhys Yorke

Kirill: If I look at your web presence on your website and Instagram, you say you are a concept artist. When you meet somebody at a party, how difficult or easy is it to explain what it is?

Rhys: I even have that trouble of explaining what a concept artist does with my family too. I refer to it sometimes more as concept design and boil it down to as I design things. I’ll say that for instance on “The Expanse” I’ll design the interfaces that the actors use that appear on the ships. Or that I’ll design environments or props that appear in a show. People seem to understand more when you talk about what a designer does, as opposed to the title of a concept artist.

Unless somebody is into video games or specifically into the arts field, concept artist is still a title that is a bit of a mystery for most people.

Kirill: It also looks like you do not limit yourself, if you will, to one specific area. Is that something that keeps you from getting too bored with one area of digital design?

Rhys: I find it’s a challenge and a benefit as well when people look at my portfolio. I have things ranging from cartoony to highly realistic, rendered environments. I do enjoy a balance of that.

I enjoy the freedom of what the stylized art allows. Sometimes I feel that you have the opportunity to be a little bit more creative and to take a few more risks. And on the other hand, the realistic stuff poses a large technical hurdle to overcome. From the technical standpoint, it’s challenging to create things that look like they should exist in the real world. And it’s a different challenge than it would be to create something that’s completely stylized, something that requires the viewer to suspend their disbelief.

These experiences feed into each other. I’m working in animation, and then I’ll take that experience and apply it to the stuff on “The Expanse”. I do enjoy not being stuck into a particular area, so I try to adapt. If someone will ask “What’s your own style?” I’ll say that it’s a bit fluid.

Screen graphics of the Agatha King, “The Expanse”, by Rhys Yorke

Continue reading »

![]() Kirill: Please tell us about yourself, and your path to where you are today.

Kirill: Please tell us about yourself, and your path to where you are today.![]()

![]()

![]()