Continuing the ongoing series of interviews with creative artists working on various aspects of movie and TV productions, it is my delight to welcome back Jessica Kender. In this interview, she talks about the impact of Covid on the industry, advances in generative AI, the art of visual storytelling, and how she does research. Between all these and more, Jessica dives deep into her work on the recently released “Daisy Jones & The Six”, and the enduring appeal of the ’70s in our popular culture.

Kirill: We talked in April 2020, right when Covid shut down everything, but it wasn’t immediately clear what would be the implications on your industry. How has Covid impacted you and your field since then?

Kirill: We talked in April 2020, right when Covid shut down everything, but it wasn’t immediately clear what would be the implications on your industry. How has Covid impacted you and your field since then?

Jessica: For “Daisy Jones and The Six” specifically, it ended up being a benefit for the show overall, because it meant that the band rehearsed for an entire another year. While we were shut down, they kept what they called “band camp” going. So by the time they came back from Covid, they did this small concert for about forty of us, and everybody was amazed how well it worked.

It did make things a lot trickier with using the venues, as we were a primarily location-based show on this one. When we were coming back, live music was coming back, which then shortened the windows for places like “The Troubadour” or “The Whiskey” and for how long they would let us in. We’d have a day and a half to prep, shoot and strike, because they wanted to get live music back in the venues. They wanted us there, but didn’t want us enough to push the bands who had blocked days out of the way.

Overall for the business, it allowed more ways of flexible working. We all realized that we could do the job remotely, at least up to a point. I have found that within my art department we can be more flexible. I said to people that I always want to have two people in the office at all times in case construction needs something printed, or whatever it might be. And then I let my department figure it out. It’s interesting, because I found that a lot of the younger people wanted to come into the art department a lot, and the older people preferred to work from home. It lets people create the work environment they want to create, and I’ve liked that part of it. That created a better work-life balance that didn’t exist before.

We’re still working crazy hours. But if I want to run to my kids school to see a performance of theirs, I can do that now where before it was never an option.

Kirill: Back in late 2020 and early 2021 I was almost 50/50 on whether the theatrical exhibition business would even survive the pandemic. Was there any pessimism that you can remember around how the industry might not survive or how the industry might get decimated?

Jessica: I never felt like this. There was worry that a lot of people were going to lose their homes, that there was going to be a lot of people going into poverty because of it. But I don’t think there was ever any fear that the entertainment industry would go away. When we were at home with the pandemic, what did you do? You turned on TV and you watched stuff? So everyone knew content was important. It was just a matter of when we would get back.

And then there was such a massive boom when we came back, and it very much reassured everyone that this industry is important. Entertainment is the way that people can forget that they’re going through a pandemic, just for that tiny little bit of time. There was not fear that it would go away, but there was fear of who would be left standing at the end of it. And now the strike is doing the same thing. Covid was the first time in my life where everyone that I worked with and was friends with, all lost their jobs at the same time. We were all out of work for months at a time, and it’s similar to what’s happening right now. You hope people have money saved, you hope we’ll get through it, but you know that there will be something to come back to.

Miami Arena, built on location in New Orleans. Courtesy of Jessica Kender.

Kirill: Speaking about entertainment as a form escapism, is it surprising to see seemingly almost no shows centered around the pandemic itself? There are maybe a couple of movies that did talk about masking and social isolation, but everything else seems to be pretend that nothing happened and the world kept on going with no pandemic.

Jessica: I was surprised by that because entertainment is almost like a mirror. When you have the best entertainment, people can either see themselves in it or imagine themselves in that situation. Removing the pandemic from entertainment was a surprise, because it was something we were all going through, and we were all scared and isolated. There were a bunch of people who were doing stuff that had the pandemic in it, and when those shows were testing, everyone was so traumatized by the pandemic that nobody wanted to have that reflection of themselves at the time.

Maybe ten years from now, there’s a show about the pandemic, and people look back and remember it. But it’s too close now. Nobody wants to go back to that world. Sometimes we want to see our own trauma and how did people relate to it, but this one was so bad that the studios maybe realized that people didn’t want it.

And then on top of that, having a mask on your face is such a big thing. It was already hard having a face to face conversation when you were both masked. Everybody remembers having to wear the mask all the time at work. And if you have entertainment where you rely on people’s facial expressions – and you can’t see them – that’s another step that is being removed in that process.

Kirill: Do you worry about the effect of generative AI down the road?

Jessica: I don’t worry about it, because I see it as another technology that can add to what we’re doing. I see what they’re doing on “The Mandalorian”, and you have this created world all around you. But then you always need to have stuff that people are interacting with. The technology will get better and better, but we’re still people, and we still want to interact with stuff. If right now my world of production design involves building the entire room, maybe it becomes building just the consoles and the stuff they’re working on – but there’s always going to be me in it. It’s reworking the way that I work.

I don’t have any interest in working in a purely AI space. That that is not what I love. What I love is walking in and seeing something that we’ve created that looks exactly like it should, seeing it and believing that it’s real. As long as something like that exists, AI can add to it. It can take us to places that I don’t have the money to build.

I worked on “Tiny Beautiful Things” and it had this dream sequence where she walks up to the top of a glacier and then looks out. You work on a half hour single camera show, and you don’t have the budget to fly to a glacier. So we built a 30×16 foot mountain side, and covered it with snow so she could interact with the snow with her feet, and you can have it along the side before she gets to the edge of this cliff and she sees this world. It was fun to do because I got to build a mountain. We carved all this foam. We played around with what snow worked. And when I looked through my camera, you feel transported to a different space.

To me, AI is another tool that adds. It doesn’t take away from what I’m doing. And I don’t think it will ever be able to fully replace what we do, because we’re humans and we need to interact with things.

Teddy Price’s house, on location in Los Angeles. Courtesy of Jessica Kender.

Continue reading »

Continuing the ongoing series of interviews with creative artists working on various aspects of movie and TV productions, it is my pleasure to welcome Benji Bakshi. In this interview, he talks about the emergence of a virtual art department, the changes it brings to the structure and the flow of the visual storytelling productions, the challenges that generative filmmaking needs to tackle, and how we as humans might be adapting and evolving as AI-driven tools are being introduced into a lot of industries. Around these and more, Benji dives deep into his work on the second season of “Star Trek: Strange New Worlds” that is streaming on Paramount+.

Kirill: Please tell us about yourself and the path that took you to where you are today.

Kirill: Please tell us about yourself and the path that took you to where you are today.

Benji: I come from a family of musicians. My grandmother was a pianist, my mother is a pianist. My grandfather was a commercial illustrator, which at the time was similar to animated advertisement. My father is Indian in origin, and came over on a Fulbright scholarship for computer science. What defines me culturally is that I have a mixed upbringing. That made it so that I almost didn’t have a culture, because it was always a mix of everything.

My parents’ inclinations inspired me to understand both sides of almost everything in life, as well as their careers. So I was inclined towards music and creativity and art and sensitivity, and also the technical side of seeing the world change with the Internet and computers exploding through my lifetime, and realizing how important that was too. It’s not that one is more important than the other.

So I’m young and I’m playing music, and I’m thinking about what I might want to do in my life. And I’m watching a documentary show on the Discovery Channel called “Movie Magic”. It was about animatronics, special effects, blowing up buildings and slow motion, and all these things. I always loved to immerse myself in that. And this documentary showed me “you can actually do this for a job?” Right after that I found my parents’ camcorder, and started running around in the backyard and thinking about telling stories. I was pulling weeds in the backyard and there were so many weeds. So I thought that these things could just overtake us if they wanted to, and I came up with a horror movie called “Weeds” where the weeds are talking to each other and trying to attack, and we have to use nerf dart guns with weed killer on the tips to thwart them. After that, making homemade movies became my favorite game to play with my friends.

While these things were running through my head as a young person, I still pursued music pretty heavily. Before I specifically decided I wanted to follow filmmaking, what really defined me was being around classical music. I’m a cellist. I was in youth orchestras traveling the world in the string quartets and doing competitions. I always felt like I was telling a story with the music. I had good training, and I was around a lot of other people who gave me inspiration to perform better, and the mix of the technical and the creative was always at play. So when I finally decided I wanted to be a storyteller, I assumed I would be a director or something because that’s the only role I knew. I followed that to Temple University for my undergrad and American Film Institute (AFI) for my masters.

At the time when I first started attending film school, they handed me a Bolex film camera to go shoot some film. They showed me how to do it, and that this is called cinematography. I really had no exposure to that, and so I thought “Wait, you can just do that specific part? You can hold the instrument and learn the technicals and then create?” You can see why that would make a lot of sense to me. This idea of cinematography as making “visual music” stuck with me since then.

The part that I enjoyed with classical music through my family history is that you can’t pursue it deeply unless it’s something you care about. The parallel I found at the time was that this was the perfect way for me to understand filmmaking as a whole – how do you actually tell a story by utilizing a technical skill to create meaning through images? Pursuing that ultimately led me to AFI where I completed a masters in cinematography and received the Richard Moore ASC Heritage Award for Outstanding Cinematography for my thesis film called Life On Earth.

Every artist and cinematographer has their own reason for what they’re doing, and things that they’re drawn to, and an internal process of how to get to an end result. Making the visual music has always been and still is my method. I have to feel it instinctually, and make sure that I’m telling a story with the images I make. At a certain point the technicals melt away, and you’re making a song with images, and that’s the movie magic to me.

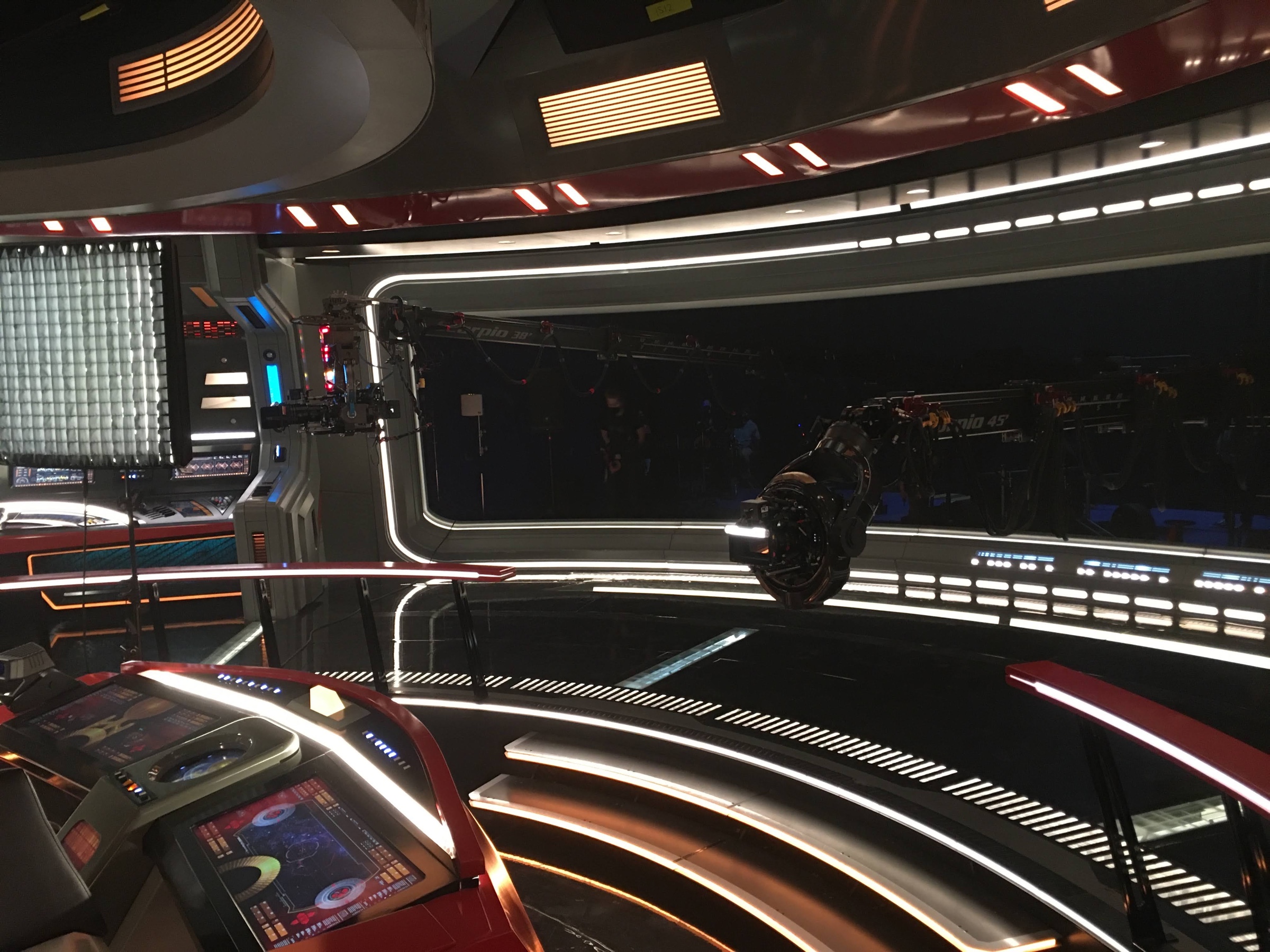

Behind-the-scenes on “Star Trek: Strange New Worlds”, courtesy of Paramount.

Kirill: There’s the intersection of art and technical craft, but you also manage people and budgets – among many other things. Do they teach all these things in film school, or do you pick it up as you go along in the industry?

Benji: That was something that was inherent at AFI. You have all the students together across multiple disciplines – directing, editing, production design, cinematography, writing, producing. As you’re required to do three short films in your first year, you have to form your own teams. They have a sign-up sheet on the wall, and when everyone decides they want to be together in this group, they all put their name and they sign it. That’s when it becomes “official”. The professors specifically say that they don’t get involved in any of the team-making process. You have to decide how to do that.

So how does one decide to find the collaborators and prove to them that you’re a good teammate? That all starts with a connection to the script and flows from there. As a cinematographer, yes your technical ability is always being judged too. And we also are required to be each other’s crew, so how do you attract each other? You help. This is a sort of politics even at the film school level, and that was structured to mimic the Hollywood industry. In that regard, when I came out of AFI, I was more prepared with that aspect of things because of it. I wasn’t thinking that I needed only to do the creative job. I knew that I needed to show my abilities and motivate a large team sometimes.

Kirill: Now that you’ve been in the industry for around 20 years, do you find that there is one skill that is the most important one to “survive” in the industry?

Benji: Be relentlessly positive. That is something that the head of the cinematography department at AFI told us on day one. This is what leads to success as a student and also as a creator in this industry. As you are telling your stories, you realize that you’re creating your own obstacles and challenges all the time – because you’re always telling a story that’s never been told before, or at least doing it in a way that’s never been done before.

Even if you’re doing a remake of an existing story, you’re probably making it a contemporary version with different techniques. You’re trying to reach and attract an audience, and sometimes surprise them, and give them a real feeling of life. They might be there for two hours, but they want to feel like they’ve lived longer than two hours. It’s a big challenge, as probably every career is, but this one is emotional.

That’s why being relentlessly positive has always stuck with me. There were many times when I asked myself “How are we going to get through this? How are we going to achieve the goals?” And we just kept finding ways to do it. There were very clear moments especially on independent films when I wasn’t sure how we could finish our day, or a complicated scene. Aside from the technical side of things and the specifics of the creativity, one of the biggest skillsets of my career is feeling like this is something I want to do, have fun doing it, and decide that you’re going to find a way no matter what.

Behind-the-scenes on “Star Trek: Strange New Worlds”, courtesy of Paramount.

Continue reading »

Continuing the ongoing series of interviews with creative artists working on various aspects of movie and TV productions, it is my delight to welcome Tom Hammock. In this interview, he talks about balancing the art and the craft of visual storytelling, the blurring lines between feature and episodic storytelling, choosing his productions, and what keeps him going. Between all these and more, Tom dives deep into what went into making last year’s breakaway horror hit “X” and its surprise prequel “Pearl” in the middle of the global pandemic shutdown, and the enduring allure of the horror genre.

Kirill: Please tell us about yourself and the path that took you to where you are today.

Tom: I have a little bit of an odd path. My father is a scientist, and I grew up helping him out with that. I went to UC Berkeley in landscape architecture, and started working in the world of architecture. From time to time, my father would be approached by movies for scientific advice, and often he would have me give them the advice. I was doing that for the Sam Raimi’s version of “Spider-Man” while working in architecture, and they talked me into doing art dept work instead. I went to AFI for production design, and worked my way up PA’ing on big movies and designing small ones. And then we got where we are today.

Kirill: Do you feel that there should be one path for people to get into the industry, or that the industry benefits from this variety or diversity of backgrounds?

Tom: It benefits tremendously from the wide diversity of backgrounds. I’ve worked with art directors who came from everything as broad as picture cars to draperies work. Those are so widely separated from one another, and yet so integral to the design and the final product of a movie. All those backgrounds are wonderful. It’s great people that come from so many different places.

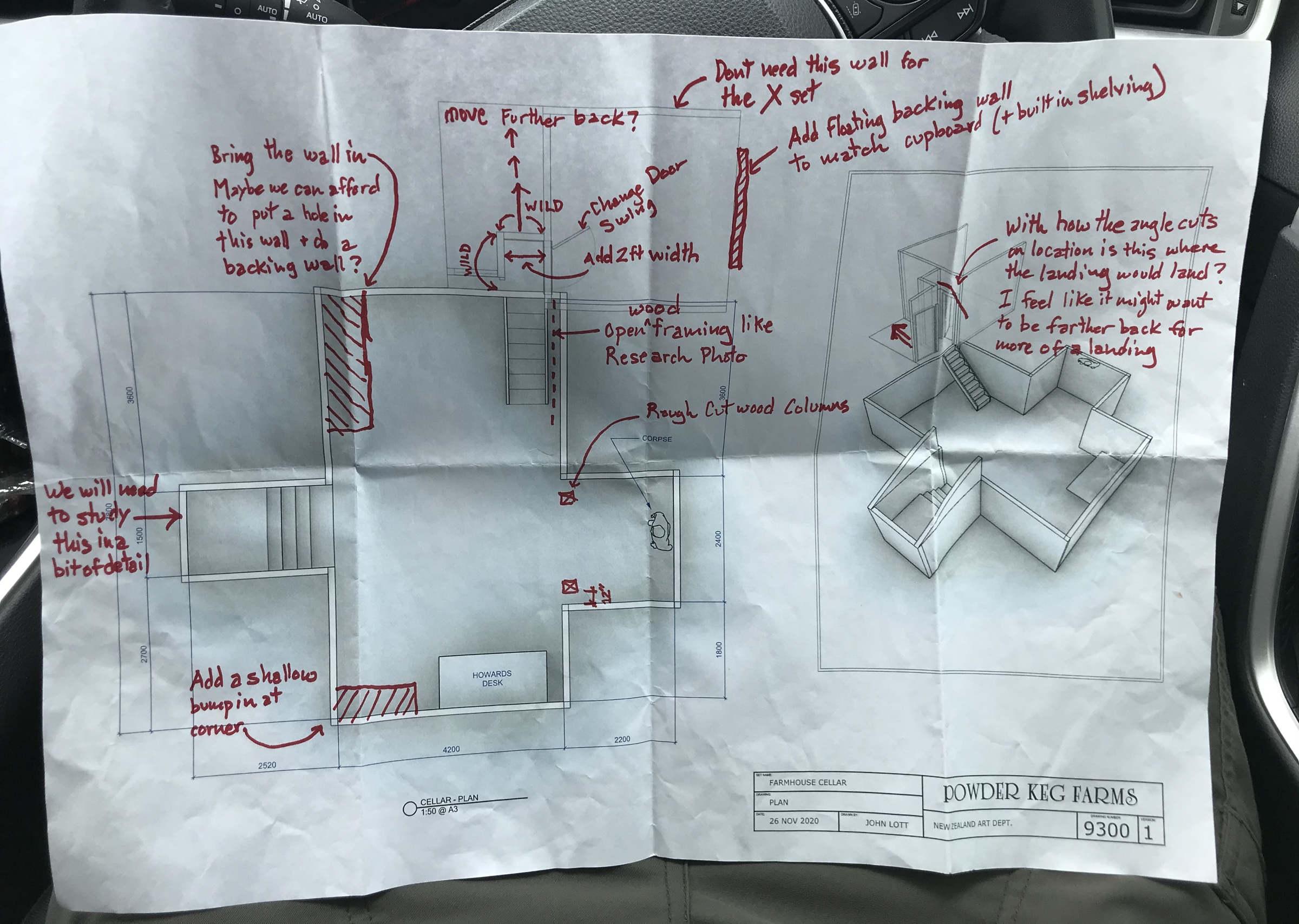

Diagram of the farmhouse cellar on “X” and “Pearl”, courtesy of Tom Hammock.

Kirill: Can you teach anybody to be not just a craftsman in the industry, but also to be an artist? Can you take anybody through an art school, and have them be an artist by the end of it – however you define what an artist is?

Tom: It really does depend how you define it. I’m always hopeful, and would like to think that you can take anybody, and teach them, and get them to a point where they can express themselves and bring their own backgrounds and ideas to bear on an artistic project in a way that maybe they couldn’t before. I do a fair amount of teaching on the side which is why I’m so enthusiastic about that.

Kirill: Is there such a thing as too many artists in the world?

Tom: Definitely not in the world. But sometimes on a project you have to narrow it down to a handful of people so that it makes it easier for the collective vision to come through – and then everybody can contribute in the way that they’re able to. Sometimes there can be too many ideas. I once worked on a project where there were two studios involved, and each studio was making a very different version of the project. That’s when things tend to go off the rails.

On the sets of the farmhouse cellar on “X” and “Pearl”, courtesy of Tom Hammock.

Kirill: You started in the industry about 20 years ago. Do you see much that changed since then in terms of where the stories are told, and the technology involved? If you jump back 20 years ago and then jump forward to today, is it much different or similar?

Tom: At its very base, it’s similar? You’re still trying to enhance character and create visual arcs in a story. And that’s never changed. You’re still trying to make the movie better.

Things are different on a more detailed and technical side. Back then, when I was shopping for a movie, I would be sent out with a Polaroid camera and a big stack of maps to go from thrift market to garage sale to rental house try to find whatever item it was for the movie. I would then come back with a big stack of Polaroid photos and spread them out and go through. That’s definitely changed, even as you’re speaking to someone who still has 10,000 feet of 35mm film sitting in his house, because I don’t necessarily want to give up the old ways [laughs].

There’s definitely been a change from hand drafting to a variety of 3D modeling and computer drafting during the course of my time in the industry. I still gravitate towards hand drafting myself, but there’s definitely been a lot of change. And then you also have the distribution aspect where you’ve had this change towards streaming television shows of various sorts, which is great. It’s more storytelling out there in a variety of different ways.

Production design of “X” by Tom Hammock.

Continue reading »

Continuing the ongoing series of interviews with creative artists working on various aspects of movie and TV productions, it is my pleasure to welcome Byron Werner. In this interview, he talks about balancing the art and the craft of visual storytelling, the transition of the industry from film to digital, choosing his productions, and what he considers to be a successful project. Between all these and more, Byron dives deep into his work on “Spinning Gold” that is hitting theaters tomorrow.

Kirill: Please tell us about yourself and the path that took you to where you are today.

Kirill: Please tell us about yourself and the path that took you to where you are today.

Byron: My name is Byron Werner and I work as a director of photography. I work in feature films, commercials, music videos, as well as a background in documentary, sports, television and other facets of cinematography.

I went to a Catholic school with a little closed-circuit television system, and that’s how I got interested in capturing images. Some friends and I would go write and make stories, and I was more interested in shooting. Shortly after that I got a video camera and started making my own little movies, and it kept going until I was in college. I applied to a few film schools, and ended up settling on Chapman University which is a film school in Southern California.

Once I got to that school, I realized that cinematography was the path that I wanted to take of all the crafts, or all the different job options. So once I did that, I did my four years and I tried to shoot as much as I could. I shot a ton of short films. I even shot a couple feature films, and just tried to build a reel and shoot as much as I possibly could.

After finishing college and trying to get a job as an AC or electrician, I started shooting, and I would PA a little bit on the side. I worked for a company at that time called Rap Patrol where they would hire us to come in and wrap big music videos. We would go and pull cable and clean up as they were shooting, and it was the hardest work you can imagine [laughs] – but I made money and I got to see all these giant music videos and these crazy big productions being made. I learned a lot and made a few bucks, and then on the side was able to go shoot movies for other people as a DP and kind of learn that way.

Kirill: How did the transition from film to digital treat you? Probably you started in the film only world and now it’s predominantly digital.

Byron: I started in the film-only world. I used to shoot a lot of really small, low-budget movies. I’d say my first 15-20 movies were on film, either 16mm or 35mm. We didn’t have a lot of money to buy a lot of film, so maybe we would get 20,000 feet of 35mm at a ratio of 1.5 to 1, so you had to be very judicious of what you shot [laughs].

At the beginning I didn’t like that transition. Film was such an amazing medium, and there was just nothing that came close to it. There was Panasonic VariCam back in 2001 which shot 720, and you had the Sony F900s, there was DV cams and then various digital cameras. And none of them were good enough. And it was hard to be able to use a real cinema lens. There were all kinds of weird ways that you’d have to find an adapter to use cinema lenses. It wasn’t a great transition when it started, but since then it’s been excellent when all these amazing digital cinema cameras have come out. Now there are so many to choose from.

I love film. Would I shoot film again? Sure, probably like riding a bike, I could do it. But do I need to? No. I love digital, I love seeing it right there, I love what you get, I love the cameras. I’m a big Alexa fan, but also from time to time I shoot RED or Sony Venice or Blackmagic. These cameras are amazing these days, and I really like digital cameras. I’ll also say a thing that may sound crazy, but sometimes film grain bothers me now. When there’s a little bit that we put on the digital, it’s fine, but when it’s really grainy – I don’t know. It’s not the same as it used to be. I like a cleaner image for the most part.

Cinematography of “Spinning Gold” by Byron Werner, courtesy of Hero Entertainment.

Kirill: You straddle the boundary between the world of art and the technical world. Do you think that anybody can be taught the technical side of it, and do you think anybody can be taught to be a good or a great artist?

Byron: I would think you could teach the technical side to anybody. It’s just something that you have to wrap your head around. I understand technical things in cinematography better than I understand physical things like construction, for instance. I can go into a computer or into camera menus and figure something out. But if you ask me to build something, I can probably do it, but it’s going to take me longer and it’s not as innate to me to be able to figure out the angles and figure out how it’s going to be done. I don’t picture it the way I do it with cinematography. But probably, if I spent a lot of time building things and got more experience, then I would learn how to do it. So I imagine that anybody can learn the technical.

The artistic side is a really interesting question. I always felt like I have a natural ability to see framing. I always thought that anybody could do it, but then I watched some friends or people frame something and it doesn’t really work, or it’s weird, or they don’t get the aesthetic of what it should look like or what is interesting. You can teach that to somebody, but there’s certain people – and I hope that I’m one of them – that the actual framing and the artistry is something that’s inside you and comes naturally.

Kirill: On the other hand, is it possible to objectively say what is good art and what is not?

Byron: I see that side of it, and the thing about art is whatever is good art often changes. If you look at cinema in the 1970s or even before from the beginning of cinema, it was not art to have a flare, and now it’s art to have a flare. It wouldn’t be art to have a lot of headroom, and now it’s art to have a lot of headroom.

And who’s to say what is art. I think that there are certain things that when you try to frame something or look at something or light something, that’s going to speak to people. And there are certain things that aren’t. Whatever you do is going to be considered art as long as it has intention, and has the intent of what you’re trying to do, the story you’re trying to tell, whatever you’re trying to have come across. Something that’s art and amazing to one person, may be just craft to somebody else.

You can claim you’re an artist by making art. Now whether you’re a good artist, that’s totally subjective as you said. But if you’re doing it and you’re making art, whatever that is, as long as you feel like it’s art, as long as your intent is to make something that yourself or somebody else can enjoy, then you can call yourself an artist – or other people would call you an artist. But then again, who cares, it’s just a title. It’s just a name. It doesn’t even matter, as long as you’re doing what you’re doing. If you’re lucky enough, in our case, to make films, then that’s all that counts.

Cinematography of “Spinning Gold” by Byron Werner, courtesy of Hero Entertainment.

Continue reading »

![]() Kirill: We talked in April 2020, right when Covid shut down everything, but it wasn’t immediately clear what would be the implications on your industry. How has Covid impacted you and your field since then?

Kirill: We talked in April 2020, right when Covid shut down everything, but it wasn’t immediately clear what would be the implications on your industry. How has Covid impacted you and your field since then?![]()

![]()