Continuing the ongoing series of interviews with creative artists working on various aspects of movie and TV productions, it is my pleasure to welcome Zosia Mackenzie. In this interview, she talks about what it means to be an artist, how she chooses her productions, the enduring appeal of the horror genre, and the potential impact of generative AI on the movie industry. Around these and more, Zosia dives deep into her work on the recently released sci-fi horror “Infinity Pool”.

Kirill: Please tell us about yourself and the path that brought you to where you are today?

Kirill: Please tell us about yourself and the path that brought you to where you are today?

Zosia: I grew up in Roncesvalles, which is the Polish neighbourhood in the west end of Toronto and where I still live today. My Dad was a lithographer so I was pretty lucky that I got to go to lots of art openings with him and that he showed me loads of really great films as a kid. I had a TV with a VHS player in my bedroom and I’d stay up really late watching and rewatching movies. Later, when I was studying film in Toronto, I interned at a bunch of studios and eventually started spending more time in New York where I got to work in the art department on a Whit Stillman film. Once I got back to Toronto I continued pursuing art department work and after a few years decided to only take on production design jobs, even if it meant I’d have to turn down some better paying gigs.

Kirill: Do you feel that there should be one path for people to get into the industry, or that the industry benefits from this variety or diversity of backgrounds?

Zosia: I definitely think the film industry benefits from the variety of people who come from all different disciplines and backgrounds. I think it’s an asset that this industry attracts film lovers but also people who come to it from architectural backgrounds, design training, or those who’ve come to film and/or design at a later point in their lives and have all different kinds of life experiences they can draw on. I think a big part of what makes this industry so special is that there’s so many different kinds of people who bring such a wide range of experiences to their work. I think as long as people can communicate reasonably well and function under pressure they can work great in this industry.

The doubler machine set on “Infinity Pool”, courtesy of Zosia Mackenzie.

Kirill: Can you teach anybody to be not just a craftsman in the industry, but also to be an artist? Can you take anybody through an art school, and have them be an artist by the end of it – however you define what an artist is?

Zosia: I think anyone can be an artist if that’s what they want to be or how they see themselves. If you really believe you’re an artist, so will others. It helps to be making things and hopefully thinking creatively and adding fresh ideas to the world. I can’t say for certain that school will make you an artist but I’m sure it can help meet some like minded individuals or connect you with teachers or industry professionals who can potentially help point you in the right direction. But, there’s only so much others can do for you – you need to be driven and self motivated and really want it yourself. Ultimately it’s up to you.

Kirill: Between the art and craft of it, you also manage people, budget and schedules. Is there any part of your daily routine that is, perhaps, a bit more boring than others?

Zosia: There’s definitely more and less exciting parts of the job. I love the early stages of a film where the key creatives are just getting to know each other, doing research and having lots of exciting early collaborative conversations. At that point there’s still so much possibility with regards to the look and direction of the film. The budgeting and scheduling can definitely be some of the less creative aspects but when you work with good people there’s less of that to worry about and I can focus more on the creative aspects.

Production design of “Infinity Pool” by Zosia Mackenzie.

Continue reading »

Continuing the ongoing series of interviews with creative artists working on various aspects of movie and TV productions, it is my pleasure to welcome Nick Matthews. In this interview, he talks about the evolution of digital tools at his disposal, how we see art, the impact of storytelling on our society, and the enduring appeal of the horror genre in the last few decades. Around these and more, Nick dives deep into his work on “Saw X”.

Kirill: Please tell us about yourself and the path that took you to where you are today.

Nick: I grew up in a family that cared a lot about art and storytelling. My dad had a master’s in English literature, and my older brother played the flute, eventually going on to Yale and Juilliard doing that. At the same time, my family was also religious, and I grew up in a conservative, fundamentalist Christian home in the South. Because of that, movies were often censored. They would look up to see what was in it before we would watch it. But in spite of that, my dad introduced us to a lot of cinema as I was growing up. I remember seeing “Lawrence of Arabia”, “The Shining” and “2001: A Space Odyssey” all very young. There was a dichotomy growing up around a culture that censored a lot of media, but then also giving you a bookshelf with Hawthorne and Dostoevsky. I grew up reading a lot of books, and that was what sparked my interest in filmmaking.

When I was in high school, I was watching behind the scenes of “The Lord of the Rings” and other big movies, and that was that era of DVDs and BluRays becoming prominent. A lot of companies invested money and time into making behind the scenes features and director’s commentaries in a way that’s not quite paralleled now. That’s when my interest in filmmaking started.

I had a friend come over one day and he said that we should make a movie together. We took my parents’ camcorder, and we shot a little sequence of someone shooting a bow and then we whip panned the camera to reveal someone that had the arrow “inside” of them. It was a fun way of starting to create a story with editing. We were doing all that on tape, and we started doing a few of those in high school and playing around together. I started writing and shooting stuff with my friends, and that was what got me interested.

I would say my path to cinematography was a lot more of a winding path. I didn’t go to school for filmmaking. I studied electronic media and broadcast, and I was making shorts on the side. I came to Los Angeles to intern on a movie as locations PA [production assistant] on a little movie called “Pete Smalls Is Dead” with Steve Buscemi, Tim Roth, Peter Dinklage and Mark Boone Junior. That was my first taste of making movies. At that time I was directing, shooting and cutting a couple of my own short films, and this was one of the first experiences I had that showed me that there are more people involved with these productions. It was an eye opener to see all the roles and all the people involved.

Right after college I ended up getting a job doing AV, projection installation and live sound. I was also shooting stuff on the side, and working for a religious organization shooting and editing a lot of their material. In the process of that I both lost my faith, and also started down this journey of trying to make movies. Eventually I had enough work to build a reel. At the same time, I was reading all the REDuser threads that David Mullen was doing. He did “The Marvelous Mrs. Maisel” and a bunch of other movies and TV shows, and he’s generous with his knowledge and wisdom. I was also reading a bunch of filmmaking books, and shooting stuff on my own. So I was learning by reading, by watching things and also by making stuff.

Then about ten years ago when I was 25, I made the decision to move to Los Angeles and start a career as a freelance cinematographer. I did a lot of jobs from Craigslist and other places, doing whatever I could to make any money. Fortunately enough, that included booking some small independent movies, which started my career shooting features. Along the way I also started shooting music videos and commercials. It’s been a slow, tumultuous journey, but it’s been really rewarding, now leading to making “Saw X”. I remember back in high school begging my dad to let me see the first “Saw”. I pushed with “Seven” and “The Godfather” and with every movie, but “Saw” was something I really had to fight for. It was so exciting being able to watch that first one, and now the chance to work on “Saw X” was a great experience.

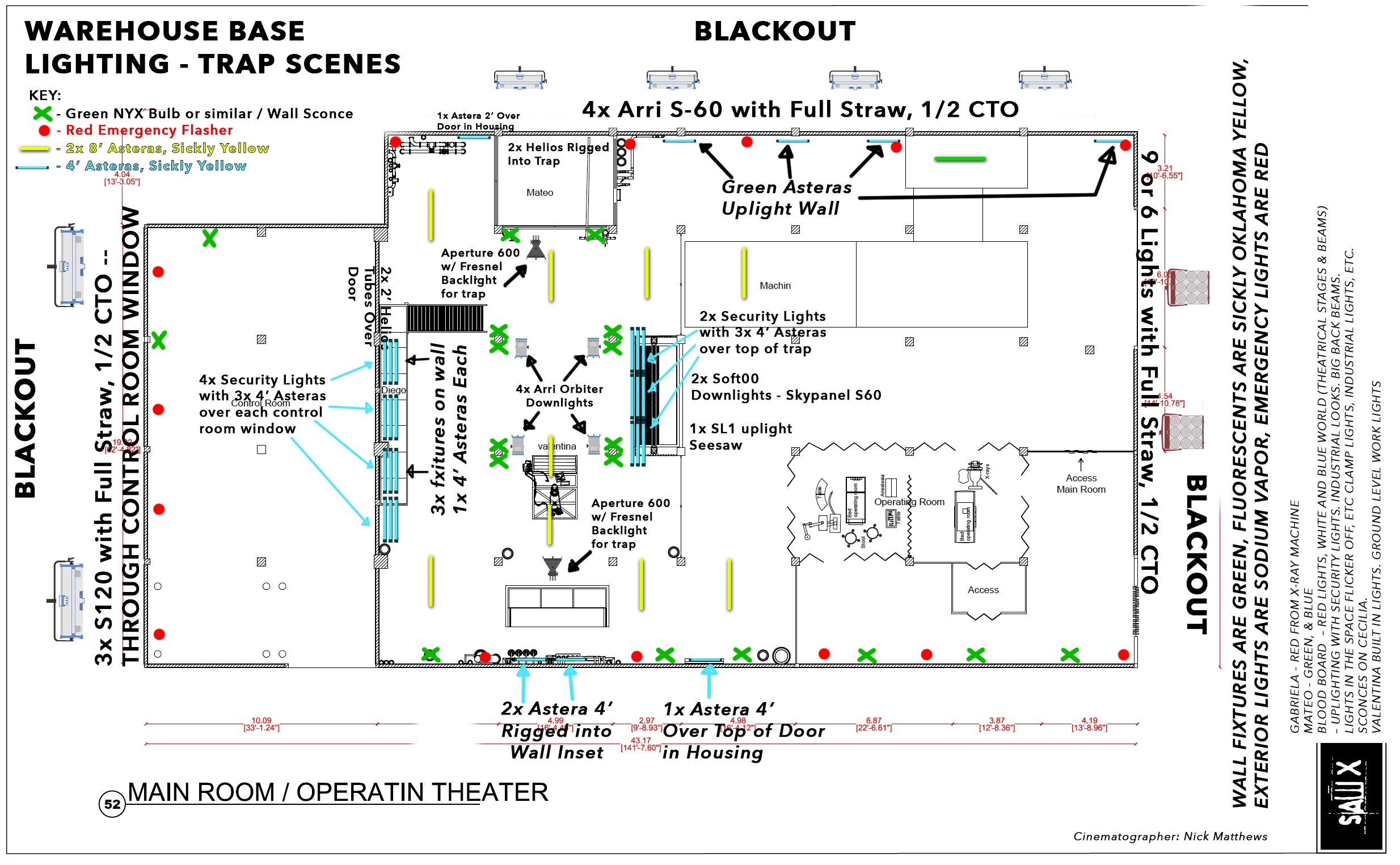

Lighting diagram of the warehouse set on “Saw X”, courtesy of Nick Matthews.

Kirill: What are your thoughts about digital vs film? Has it been settled by the financial side of it, with film remaining more of an eclectic choice?

Nick: In some ways, I am a product of the digital era filmmaking. I started my career shooting on MiniDV and 3-chip Ikegami TV broadcast cameras. Then we used 1/3 inch cameras like HVX200 and And then I kind of walked through the like third inch chip cameras, like the HVX200 and the XL1. It’s been this whole progression of technology that has directly impacted my life and my career. It moved to the CMOS sensor DSLRs, and then eventually starting to shoot on the RED and Alexa.

To me, film always felt untouchable because it was a process and a format I didn’t fully understand. There were more upfront costs with development and with procuring the film itself, and so it felt a little off the table for me. Eventually, I convinced a friend of mine to shoot a music video on 16mm. We did that a couple of times, and I got a chance to experience that.

I love the way that film looks. When I see it as a viewer, it has an impact on me. There is something about it that feels painterly, there’s something about it that does feel textural. It’s the way that it reads colors, the way that it reads highlights. There is something about it that doesn’t feel so hyper-real and so present tense, and something about that really immerses me into a story.

That said, the majority of my career has been shot digitally. I would say there is an acceptance of what digital brings to the table. The director of “Saw X” Kevin Greutert came from the days of editing film on negatives, and he has no interest in ever going back to film in any world. There’s a lot of complexity to the process with film that could result in you losing your material. You don’t have immediate feedback, you can’t immediately see where you’re shooting. If something’s out of focus or the negative is scratched, you don’t immediately know. If you flash the negative, you don’t immediately know. It’s a scarier process. There’s a bit of taking a leap. I remember on one of the projects I shot on 16mm, we were shooting at one frame a second, we were doing 360 degree shutter and doing pretty wacky things with the camera – and you have no immediate feedback.

There’s a lot artistically to love about film. There’s a lot of challenges to the process. Both film and digital exist. There’s a reason huge movies are still being shot on film and projected on film. I hope that film stays around long enough for me to shoot a feature on film. I love the way it captures images. At the end of the day, I’m pushing a lot of my digital work to try to look more like film.

That said, most projects do shoot digitally right now. You really have to fight to shoot something on film and you have to fight for that budget. For some people it’s worth it and for most it’s not. Digital has a lot of convenience to it. There’s ways to use digital photography to do things you could never do on film. It’s better with low light. Cameras can get smaller and smaller to the point that we’re able to put them in places we’ve never been able to put them before. It can capture certain color tones that were not capturable prior. There’s a lot about shooting digitally that’s beautiful.

You look at the evolution of digital cameras with RED M, RED MX, ARRI ALEXA, ARRI Mini LF and others. All of these camera systems have brought something to the table. And I’ve had the great fortune of being able to use them on some of my own work. You look at a movie like “Zodiac” that was shot on Grass Valley Viper at 1920 resolution back in the days of early digital cinema, but it was Harris Savides who’s an absolute master. It looks fantastic even now, because the people that are crafting the film ultimately matter more than the gear. But I would also strongly argue that the gear directly affects the story that you’re telling. If you try to shoot a certain movie on an XL2 or an old mini camera or DSLR, it will directly impact the images that you capture, as well as the way in which you move the camera.

I love that we have both. I hope we continue with both for a very long time.

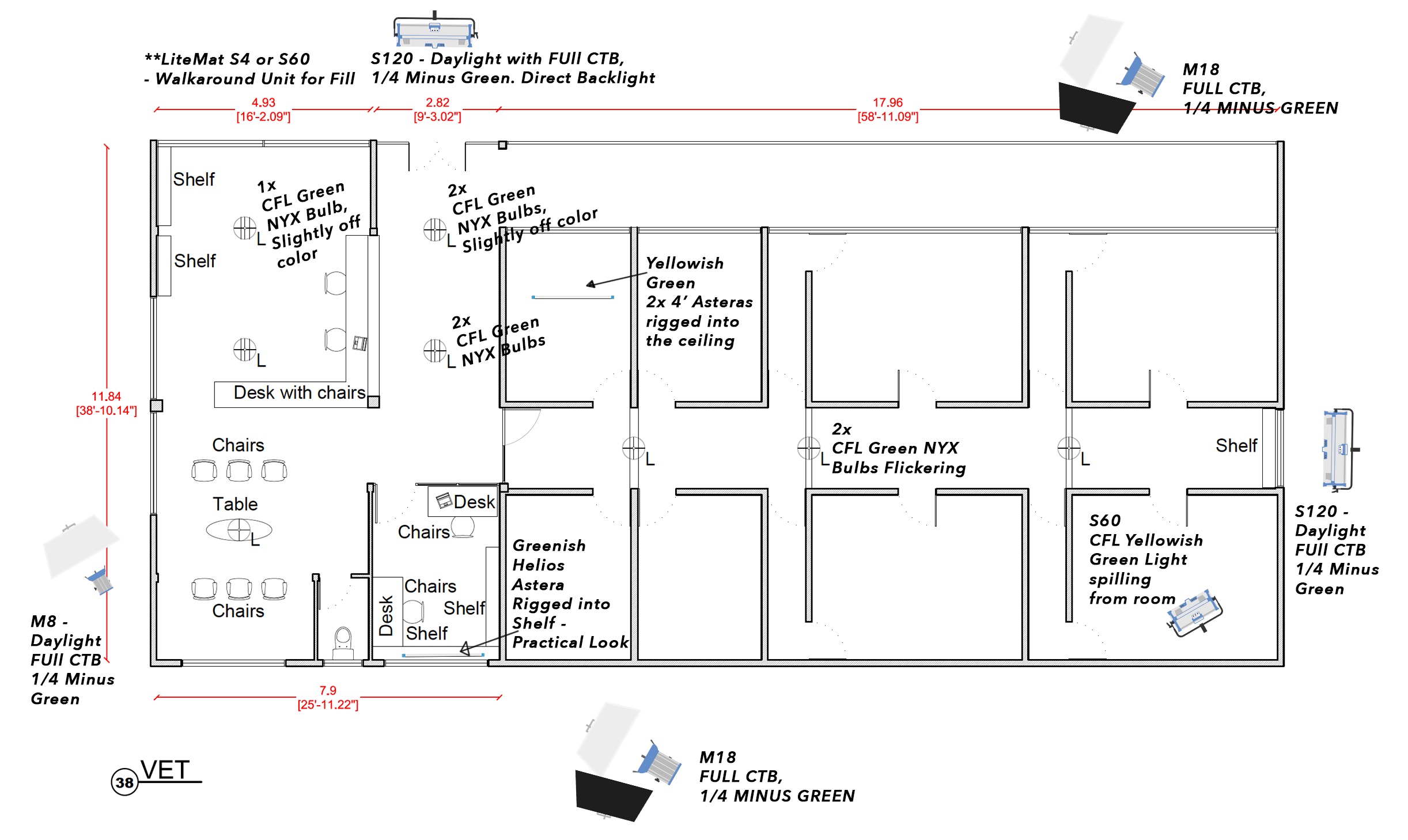

Lighting diagram of the vet set on “Saw X”, courtesy of Nick Matthews.

Continue reading »

Continuing the ongoing series of interviews with creative artists working on various aspects of movie and TV productions, it is my pleasure to welcome Jaron Presant. In this interview, he talks about how the industry is changing with evolving technology, what he looks for in this collaborative medium, the balance between the art and the technical side of things, and our need for storytelling. Around these and more, Jaron dives deep into his work on the first season of “Poker Face”.

Kirill: Please tell us about yourself and the path that took you to where you are today.

Jaron: I was always fascinated with film as a kid and how it can take you into this other world. When I was 12, I got really interested in still photography, and at the same time I was fascinated with special effects in movies – how they did monster makeup and things like that. So when I got a driver’s permit, I interned with a special effects artist that worked out of his garage in Burbank. I thought he was the greatest thing since sliced bread.

One day he said that if I want to get into this, I should be sculpting. So I went home, got some clay and tried to make a hand. And I remember it was so bad, that I was thinking that I had no talent in this, that I should give up now. But I was also doing photography, and when I got onto a set and saw what the cinematographer was doing, I saw that it was so much like the photography I loved. To me, still photography at the time had seemed lonely as a career, and cinematography seemed to hit all of the areas I was interested in but in such a collaborative environment. I started interning with the cinematographer, Tom Richmond, and then began working in the camera department. I also went through the electric department learning lighting, and I went from a film school. I did all of the paths you could possibly take to get to be a cinematographer.

Kirill: So how do you feel the industry around you has evolved since you joined it?

Jaron: There was the obvious change from film to digital, which was slightly inconsequential since although it replaced one medium with another medium – the concept in the process is still the same. If you’re in control of your process as a DP, understanding the latitude you’re working with of your medium and lighting for that latitude, the medium change isn’t all that impactful.

The thing that has changed tremendously is the concept of feedback loops, and how we get feedback from sets and from the process of filming. It used to be that the director of photography was the only person who understood the image at its core – and arguably, that is still the case. But the process now is open, because we can see the final image so much quicker. It opens the door for so much more feedback from people who traditionally either didn’t have input or the input was at a much later point where it wasn’t as impactful, and that has changed how the process of filmmaking happens. You get more feedback quicker, and it’s exciting. It means we can iterate and make changes, which is a process I hold dear. The process becomes one of way finding and prototyping.

That’s how I approach imaging, and it’s how I’ve approached imaging since it was on film and I was with a still camera. I snap lots of photos and fine-tune my eye through the process of iteration. Now, with digital imaging and the process being opened up to more people that can have input, this process is faster and more present.

Camera mount on the process trailer for “The Hook” episode of “Poker Face”, courtesy of Jaron Presant.

Kirill: Is there such a thing as too much feedback?

Jaron: Absolutely, a hundred percent. That goes back to having our own discipline. We choose to say that we don’t roll the camera all the time. We choose to dictate that we start and stop the camera, that we reset for takes – and that’s a discipline. And in much the same way, figuring out who the people are that are having input, and how we manage that input – that is a discipline. If you set up the system well, the rewards are extraordinary.

I use a viewfinder that attaches to an iPad called the Artemis Prime, and it’s a bit clunky to be honest. But the reason I use it and the reason it is great is because I don’t need to rely on somebody else to line up a shot after we’ve marked the spot. You don’t need to hope that you’re getting this tree on the right side of the frame, or that you’re getting the composition that you want. You can physically put it in front of the director and myself and sometimes the production designer, depending on who we want involved. You can look at things and discuss them. You can make changes quickly and take the image to a place where it wouldn’t have gotten to without that kind of feedback.

Jaron Presant on the set of “Mr. Corman”.

Continue reading »

Continuing the ongoing series of interviews with creative artists working on various aspects of movie and TV productions, it is my honor to welcome Cary White. In this interview, Cary talks about coming out of retirement to join the sprawling universe of the Dutton family, from the original “Yellowstone” to its prequels “1883” and “1923”.

Cary White on the set of “1883”.

Kirill: Please tell us about yourself and the path that brought you to where you are today

Cary: I started off as an art major in college. My mother always encouraged me as an artist, but my father was convinced that I would surely starve to death with a degree in Art. So anyway, seeing how many talented people there were out there and how all my roommates were studying serious stuff, I decided to give up on art. I changed my major to Business Administration and I got a degree in that, but it never converted me into a businessman and it was boring as hell.

But, then one day, while I was bored to death, I was thumbing through the University of Texas course catalog and discovered that I could actually get college credit for going to movies. I was hooked. I thought “going to movies is something I can do all day long!” and so, I ended up with a Master of Arts Degree in film and ironically, I’ve ended up as the head of the Art Department – back in ‘Art’ after all.

Kirill: Do you feel that there should be one path for people to get into the industry, or that the industry benefits from this variety or diversity of backgrounds?

Cary: Given my random path into the film industry, I would be the last person to think that there should be only one path into it. I think filmmaking is a collective and synergistic art form and that different people with different backgrounds all bring something special to the party.

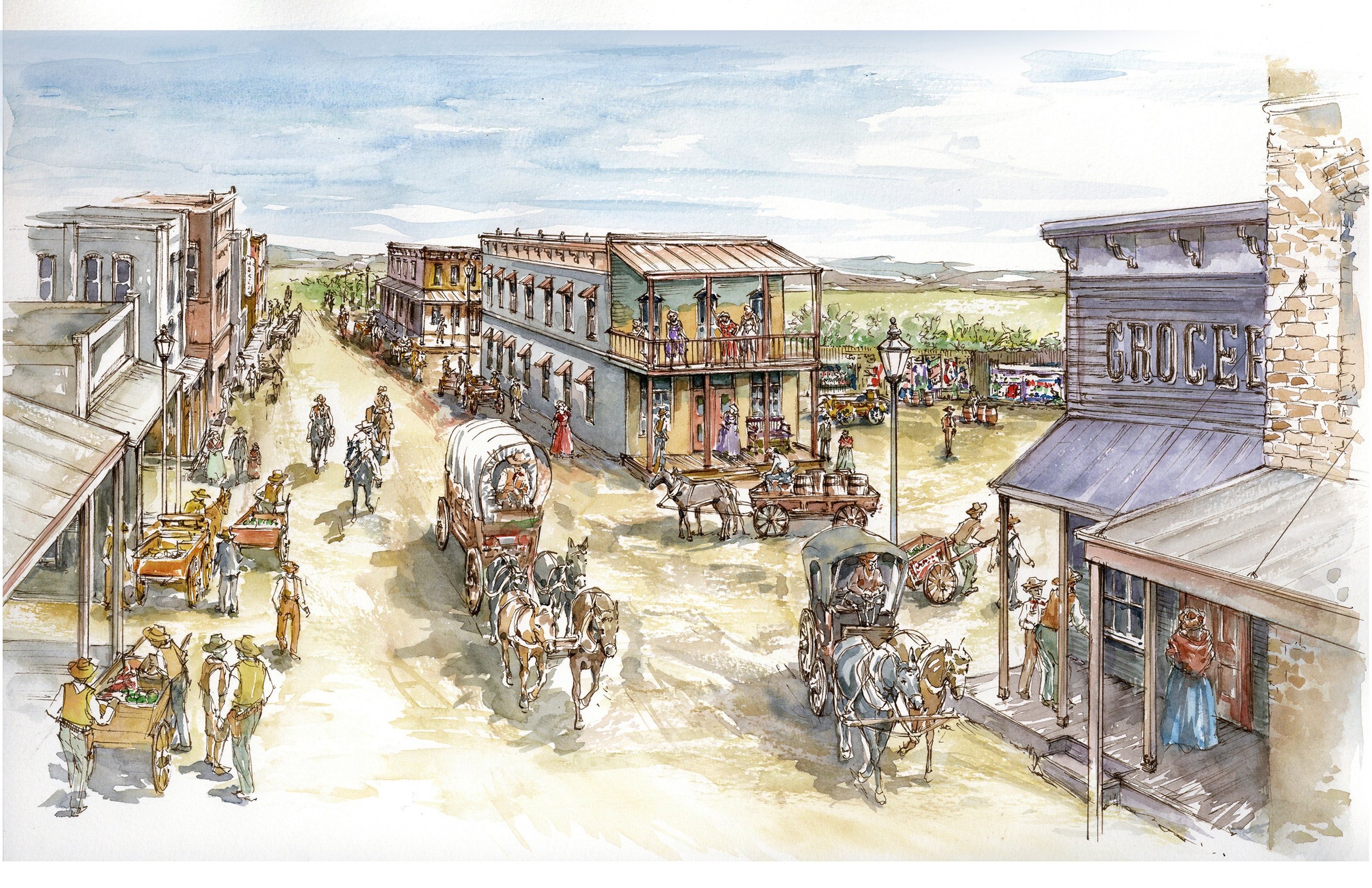

Rendering of Hell’s Half Acre in “1883”, courtesy of Cary White and Paramount.

Kirill: Can you teach anybody to be not just a craftsman in the industry, but also to be an artist? Can you take anybody through an art school, and have them be an artist by the end of it – however you define what an artist is?

Cary: I have trouble calling myself an artist. It sounds too pretentious for me. I work with people who are extremely talented and I consider them to be artists. Collectively, we try to make art and I think our combined product can sometimes be greater than individual talents. One thing that I think is more important than a technical skill like drafting, for example, is the passion that a person has for what they’re making.

Production still of Hell’s Half Acre in “1883”, courtesy of Cary White and Paramount.

Continue reading »

![]() Kirill: Please tell us about yourself and the path that brought you to where you are today?

Kirill: Please tell us about yourself and the path that brought you to where you are today?![]()

![]()