Continuing the ongoing series of interviews on fantasy user interfaces, it’s my honor to welcome Jamie McCallen. In this interview he talks about keeping the viewers in the story, the process of designing for screens in film, the differences between on-set and post production work, and the evolution of hardware and software tools at his disposal. In between and around, Jamie dives deeper into the first 15 years of his work that spanned productions as diverse as “Elysium” and “The Age of Adaline”, “Batman v Superman” and “Night at the Museum: Battle of the Smithsonian”, “Star Trek: Beyond” and “Godzilla”, and many more, including his most recent work on “Altered Carbon”, “Skyscraper” and “The Cloverfield Paradox”.

Kirill: Please tell us about yourself and the path that took you to doing screen graphics in film / TV.

Jamie: I am a freelance designer and developer based in Vancouver, Canada. Over the last 15 years, I have worked on just over 40 film and television productions providing interactive desktop and mobile applications and post-production motion graphics.

I took a bit of a detour before getting into the industry. Art and programming had been interests, but I always had a different career in mind. In my teens, I had had art lessons, attended summer computer camps, that sort of thing. In my first years at university, I had taken a few programming courses and I worked one summer developing research applications for a statistics professor. But my intended career path was law and labour relations and over the next few years that’s what I did: law school, human resources manager, lawyer, co-founder of a labour relations non-profit organization. To that point, I had enjoyed the work I was doing, but it was while building the website for the non-profit, that something clicked. I realized I was excited about what I was doing and really enjoyed the combination of coding and design. Not wanting to give that up, I started working with a Vancouver-based team building websites for game companies and their game titles.

Around this time, I had a chance encounter with Rick Lupton, owner of i.Solve, Inc. Rick had heard I was doing some work in Director and inquired if I could build a joystick-controlled gimbal screen for the x-jet in “X2: X-Men United”. Over the next few years, I worked with the i.Solve group and started to design more and more screens.

It would take a few more productions and the opportunity to work with Gladys Tong and the G Creative team before I stopped thinking of myself primarily as a developer and started to consider myself a hyphenate (designer-developer).

Screen graphics for “Godzilla” under the creative direction of G Creative. Courtesy of Jamie McCallen and Warner Bros.

Kirill: Looking back at your first couple of productions, what was the most unexpected part of working in film?

Jamie: On the first couple of films I worked on, I remember chasing some information that I thought would be helpful while building screens. “What city are they in? What is the last name of that character? What is the exact date?” It took a while to figure out there were often no solid answers and that productions sometimes wanted to keep those aspects as vague as possible on purpose. It just became easier to work around the details and get creative about hiding the holes. Nevertheless, I just remember expecting some of those details, especially timelines, would have been fleshed out.

Kirill: Do you worry about how your work will age / be seen in 20-30 years?

Jamie: Considering some of my work is nearly 15 years old, I should probably start to worry. But, no, I don’t worry about it. Style and design are a product of their time and some will age well, and some won’t.

While designing, I am definitely not thinking about future audiences. But I do have the contemporary audience in mind and am considering what they are familiar with, what visual shorthand can I use to reinforce the message. Mainly, I am trying to produce a style that matches the character and the set design. When my work is seen by future audiences, I just want it to continue to mesh with the overall production.

Screen graphics for “2012” under the creative direction of G Creative. Courtesy of Jamie McCallen and Columbia Pictures.

Kirill: Do you find yourself competing with screens in your daily life? How do you craft something compelling that keeps the viewer in the story?

Jamie: Absolutely, I think we all compete with screens to some extent. It’s fairly common to be in situations where a person you are with is trying to finish up a message or post. For the most part, I just keep doing my own thing. If the person knows I am there and chooses to continue with what they are doing, I’ll respect that choice.

It’s kind of the same way in movies. You need to know what your message is competing with and how important it is. It’s not always about demanding attention.

As for your second part of your question, keeping viewers in the story. That’s key. We have all watched a show where something was off. Display graphics can suffer from the same types of problems. Sometimes they can be overly distracting, have awkward mannerisms, look out of place.

So, the first part of designing any screen is to just try to make sure it doesn’t stand out for the wrong reasons. Screens have to play their role. If it is a background textural screen, it should not call too much attention to itself. If a screen is given the chance to drive the story – be a “hero” – it needs to command attention and, as you said, be compelling.

To build a compelling hero screen, I think it should offer something unique and it needs to read clearly. For me, the process starts with the message. What story does the screen need to tell? Usually a screen is only visible for a few seconds, so it is important to figure out the core of the message and eliminate anything else. I try to strip out anything that I can read past and still get the whole message. Some of what is stripped out can be reintroduced later as secondary elements, but the main message should be as simple as possible.

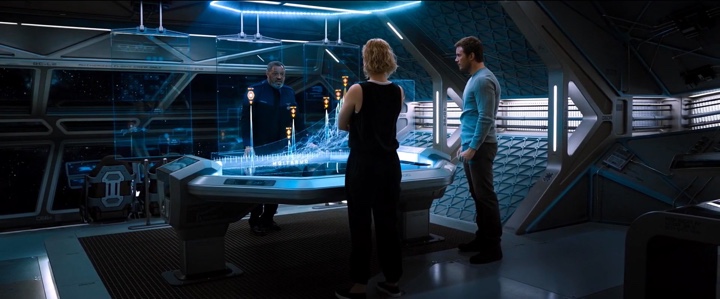

Screen graphics for “Star Trek: Beyond” under the creative direction of G Creative. Courtesy of Jamie McCallen and Paramount Pictures.

Continue reading »

Continuing the ongoing series of interviews on fantasy user interfaces, it’s my pleasure to welcome Bruno William. In this interview he talks about self-initiated work, VR interfaces, invisibility of good design and screen graphics in film and episodic television. In between and around, Bruno dives deeper into his work on the recently released first season of “Lost in Space”.

Screen graphics for “Lost in Space”, courtesy of Bruno William.

Kirill: Please tell us about yourself and what brought you to where you are today.

Bruno: I’m a designer based in São Paulo, Brazil. I always loved video games, music and movies, as well as martial arts. Art and design were always present in my life, directly or indirectly. Since I was a kid, UI or fictional technology was always being there in movies like “The Matrix”, “Terminator” or “Alien”, even if at that time I hadn’t realized it yet.

The Internet was my main source for study when I started out. You study and talk to other artists and designers, and absorb the knowledge. For me, that process still goes on today, and I’m still passionate about UI design, technology and storytelling.

The Internet was my main source for study when I started out. You study and talk to other artists and designers, and absorb the knowledge. For me, that process still goes on today, and I’m still passionate about UI design, technology and storytelling.

I was studying a lot of things like CGI, 3D character design, motion design – all by myself, even when it was frustrating. I knew that I wanted to work in the entertainment industry, doing art or design for film and video games. As I was trying to find myself or do something that I loved, I found the UI work that Ash Thorp was doing for film. That was a pivotal moment for me, to see all that knowledge and the way he approached it. It gave me a bit of confidence to pursue what I love.

Those were my early inspirations, artists like Ash, Nicolas Lopardo, Alan Torres and Jayse Hansen, whose work I was studying at that time.

Self-initiated work by Bruno William.

Kirill: I saw a number of self-initiated projects in your portfolio. How do you approach starting a project without any specific requirements about it?

Bruno: I always struggle with personal projects, and I think that’s expected when you’re starting out as an artist. When you work for a client, you have some kind of direction or a “problem” to be solved. When I do a personal project, my goal is to study and understand what I have to improve.

I usually try to create a quick story behind the project. That way I can have a topic or two that can help me with my creative process. It’s common to say that you need to do a personal project, but you’re not sure what you want to do or what you can do. The best thing for me with my personal projects is to create the problem in my head, and then work to solve it.

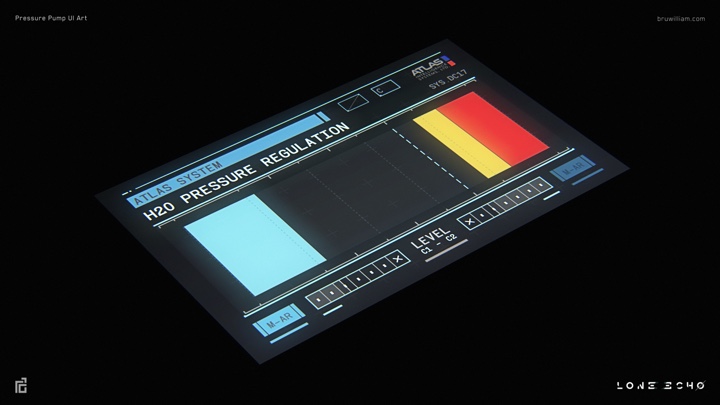

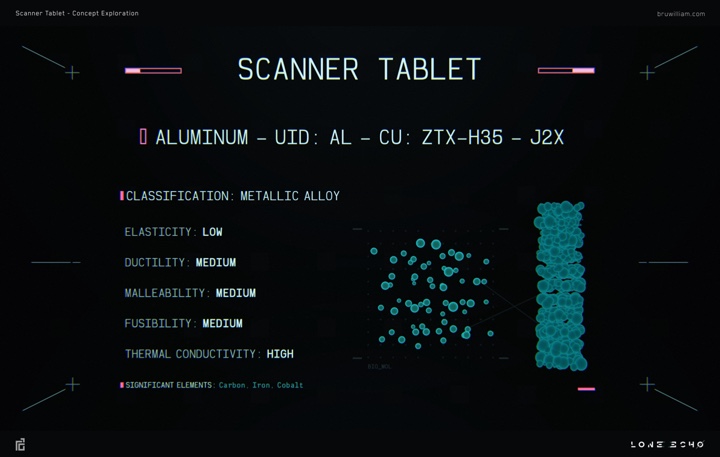

Screen graphics for “Lone Echo”, courtesy of Bruno William.

Kirill: What can you tell about the project you did on designing a game interface in VR?

Bruno: That was “Lone Echo” and it was a huge challenge. It was my first AAA-game, and it was my first time working in the field of VR in general. You usually create 2D, flat screens for devices that the user can touch or interact with physically. With VR, the question becomes how do you organize that information in a 3D space around the player.

The most challenging thing on this project for me was to figure out how to make the information clear and functional to the player in 3D space. How do the elements interact with each other, as well as with the player, in an intuitive way?

When it comes to design, it needs to be rooted in basic principles. We need to keep things simple as much as possible. Everything needs to be easy and readable. If we use tiny details or thin lines in VR, it can be annoying for the players. Reading and understanding a small text element in the 3D space can be a frustrating experience from the readability perspective.

On “Lone Echo” everything needed to be bold and readable. It had to be structured and organized, avoiding tiny details.

Screen graphics for “Lone Echo”, courtesy of Bruno William.

Continue reading »

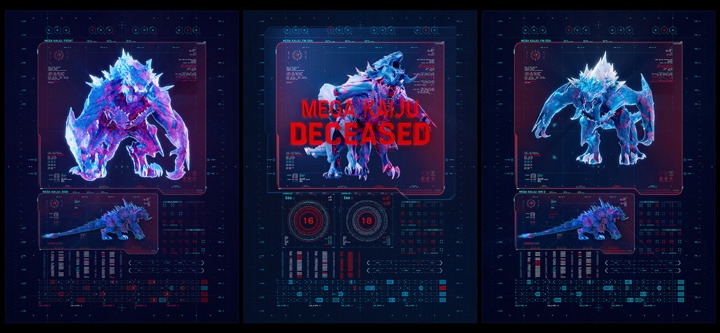

Continuing the ongoing series of interviews on fantasy user interfaces, it’s my pleasure to welcome Daniel Højlund. In this interview he talks about the evolution of motion design in the last ten years, his work process, the balance between ideas and tools, and the pace of working on big sci-fi film productions. In between and around, Daniel dives deeper into his work on “American Assassin”, “The Martian”, “Blade Runner:2049” and the recently released “Pacific Rim: Uprising”.

Kirill: Please tell us about yourself and the path that took you to where you are today.

Daniel: My name is Daniel Højlund, and I’m a motion designer from Denmark. I first got started in this field about 10 years ago, but my interest in computer graphics dates back to my late childhood when through my mum’s work computer I got access to a few fun games and programs. I’ve always been interested in using computers for something in my career, as soon as I realised becoming a football (soccer) player wasn’t going to happen, even though I wasn’t quite sure what I wanted to do with it, or what that job was going to look like.

I started as a multimedia designer in 2007, and back then I actually thought I was going to be a Flash web designer. Today I still find that quite difficult to fathom, but back then it was quite a hot thing, and it was only by pure coincidence that I kind of stumbled upon motion graphics when I did my final semester as an exchange student in Kuala Lumpur in 2008. The university had a two-week introduction phase to different creative courses that you were able to take. It was everything from photography, video editing, classic 2D animation, drawing, or more technical 3D classes etc.

One of the courses was called ‘motion graphics’. I was intrigued and joined on a two-day introduction course to it. Amongst the showcases was some cool MTV idents and I was instantly fascinated and taken by the possibilities and the coolness of it. It looked like so much fun creating it, and even though I had seen similar stuff on TV many times before, I could not believe that this was actually a profession and people got paid to do this. I was on the path to becoming a web designer, but I pretty much instantly ditched that and went all in on the motion design course and hoped for the best.

Screen graphics for “Pacific Rim: Uprising”, courtesy Territory Studio.

I passed, but when I came back there wasn’t really any motion graphics work around in the city I lived at that time, and I ended up spending a couple of gap years working various jobs and traveling and doing some personal motion projects on the side. I could not let go of it. Then in 2011 I found this interaction design degree in Copenhagen, which had a motion design module. I applied and was fortunately accepted in.

During that degree I went to Melbourne, where I studied for half a year as an exchange student again. I took courses in 3D character modeling and rigging, as well as classic 2D animation. After that I got an internship in London at Territory Studio, when David Sheldon-Hicks decided to take a bet on me, which has now set the path that I am currently on today.

After the internship, I went back to Copenhagen to finish my degree. Straight after that summer I moved permanently to London where I started out freelancing, but eventually became a full-time staff member at Territory, where I ended up spending altogether 5 years. I was there up until recently, and this August I decided to relocate to Copenhagen where I’m now starting life as a freelancer.

Kirill: Do you think it’s easier to start in the field today than it was 10 years ago? There are more tools at your disposal today, but the demands are a little bit higher and you need to know more about those tools.

Daniel: It depends on what is being asked of us in terms of the work. When I first graduated back in 2008, there wasn’t a whole lot going on in Denmark at that time. I believe I managed to find 3 places that did a little bit of motion design work, and this was in the second largest city in Denmark (not that it counts for much on a global scale!). Compared to 10 years ago quite a lot has happened with handheld smart devices for example, and today we have screens existing everywhere around us, and on us, and there is a much larger demand for more people to output content. So even though there is way more people doing motion graphics today than a decade ago, the demand for content has exponentially increased as well with the amount of platforms that needs to be populated.

Screen graphics for “Pacific Rim: Uprising”, courtesy Territory Studio.

In terms of getting work I think there is a lot out there — every company, tv show, brand, artist, sports franchise, social media – you name it – are demanding video content in some forms these days. The competition is obviously very high for the most prolific big name jobs, but that will always be the case in any industry, and follow trends. But maybe those jobs are not what you want to be doing, and maybe you want to make more meaningful content in other ways, whatever that is to you personally. Try and get an idea of what type of work you want to be doing, and not just run aimlessly in the direction of everyone else just for the sake of it. Chances are you won’t arrive at a very happy place, if you make it there.

In terms of learning the technical skills and how-to’s in the softwares used for motion design is far better today, than 10 years ago — purely due to the amount of high quality training content that lives online now. The amount of knowledge sharing online today is tremendous and it will only keep on increasing. In that sense I guess it’s a little easier and more straightforward for anyone to give it a go.

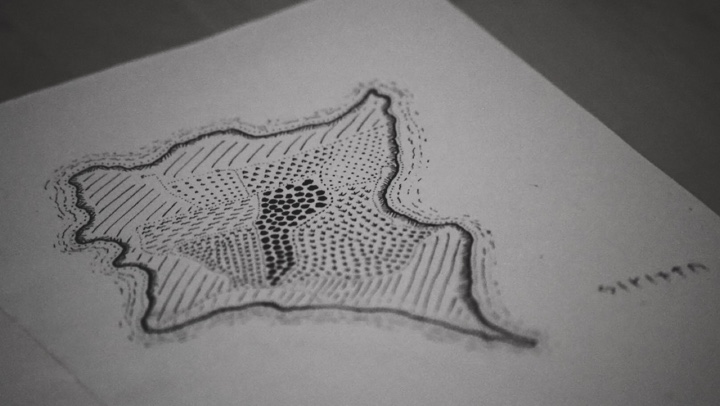

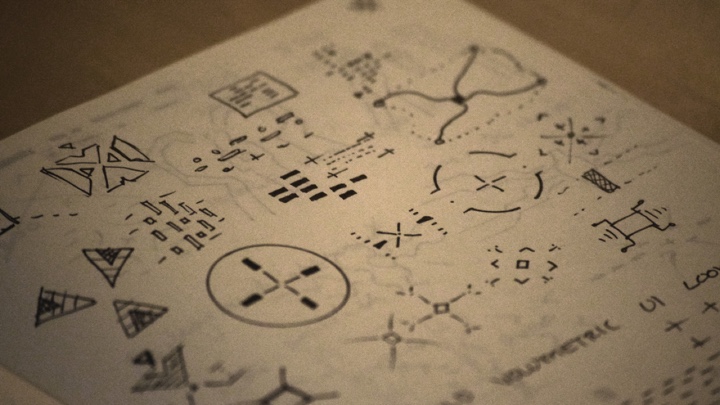

From Daniel Højlund’s sketchbooks.

Kirill: I found these lovely hand-drawn maps that you posted recently to your Instagram stream. When you start a new project, do you find yourself sketching on a piece of paper, or do you go exploring the digital realm?

Daniel: It depends on what the task is at hand, I think. Generally I start scribbling down early on and get any immediate thoughts down on paper. I find this process fast, and it comes from a place based on your intuition and gut feeling, and is not yet stained and influenced by external noise.

There’s usually something that naturally surfaces that you might want to note or sketch down before you start numbing it with endless browser scrolling and screen glaring. That said, Pinterest, Tumblr, Behance, ArtStation, you know the drill, also has their part to play. Those are great places to be inspired and get exposed to new work that others are putting out there, absolutely. But, it can also be an endless maze if you don’t set yourself some boundaries. I try to set myself a framework prior to doing my online research — maybe this is a time limit for myself, or try to see if I can define something tangible of what it is I am actually looking for before I start scouting the web for something I don’t know what looks like.

In terms of starting on paper – and let’s make it a UI example – it may for me just be defining a composition and figuring out where certain elements need to be going. It may be a rough idea of form, areas and sizes, and the relationship between the hero component in the screen and the smaller graphics. It might consist of some quick shapes, dots, linework and type drawing that comes to me, to see if there’s some interesting elements or constellations to explore. I then find it easier to open Illustrator and start creating the design if I already have a rough visual idea in my notebook of where things go, or roughly look like. I’m terrible at drawing but jotting down some simple bits like these and giving myself some visual references before I sit down in front of the screen, helps me to free up some mental headspace to focus on the design, and find my flow and stride faster, as I have already made some considerations.

From Daniel Højlund’s sketchbooks.

Continue reading »

Continuing the ongoing series of interviews on fantasy user interfaces, it’s my pleasure to welcome James Brocklebank. In this interview he talks about the ever-evolving set of tools at his disposal, the increasing demand for motion graphics world in film and other fields, working on load movies for video games, and being a part of huge sci-fi film productions in the last few years. In between and around, James dives deeper into his work on video games such as “Call of Duty: Black Ops” and “Titanfall 2”, as well as screen graphics on “Passengers”, “Ghost in the Shell” and the recently released “Pacific Rim: Uprising”.

Screen graphics for Ghost in the Shell. Courtesy of James Brocklebank.

Kirill: Please tell us about yourself and what brought you to where you are today.

James: I am a motion designer based in London, UK. I’d always loved drawing as a kid and studied art throughout school. It was when I was doing my Fine Art foundation course at Art College in Hastings, that I first discovered Photoshop and that steered me towards doing a degree in Graphic Arts and Design at Leeds Met University, where I specialized in photography, image manipulation and film making.

Once I left Uni, I became a runner, essentially a tea boy, firstly in an editing facility in London and then at a VFX house.

Once I left Uni, I became a runner, essentially a tea boy, firstly in an editing facility in London and then at a VFX house.

All the while I was working in the evenings on my own portfolio and trying to learn as much software as I could. Then I got a job as a junior designer in motion graphics, first designing DVD menus and then working in music, making commercials for albums, promos, content for award shows and the odd CD cover, which was great, as CDs and music videos were some of the things that got me into wanting to do graphics in the first place.

I went freelance about 2008 and since then I’ve worked across a wide range of projects for a variety of clients. From broadcast, live concerts, projection mapping, branding, commercials, computer games and more recently I’ve been doing some film work which you’ve seen.

Kirill: Between the powerful digital tools at your disposal and the ideas in your head as the designer, is there more importance to one than the other?

James: I primarily start with the ideas. That can be the brief from the client or a self initiated project. If you’re doing film work, there’s the director and a hierarchy of people who have their own visions. The tools are there to facilitate you executing their visions.

That said, sometimes it can be a little seed of an idea that someone has, and that’s where you then go and explore. That’s where the software comes in amazingly handy, because you don’t actually know where you’re going to go. You’re experimenting and that’s why I really enjoy the look development stage. You’re playing around, pushing the software to see what it will do, exploring different approaches.

Kirill: In my little part of the world, there’s usually a team of designers that work on the overall experience, and the particular parts of it, like visuals, animations, overall flow. And then there are developers that take those mock and implement them. Does it feel that in your field you’re wearing both hats at the same time?

James: I come at it from a drawing/art background, but you need technical skill to make a living in this field. There’s a lot of software I have learned since the beginning of my career. The technology has developed massively, and with that the responsibility of what you need to know for each job has increased exponentially. I primarily work within motion design, but a lot of the jobs I now work in are more of a visual effects pipeline, which encompasses everything from 3D animation, compositing, simulations, camera tracking, etc. Not that I need to know all of the software that comes with that, as there are a lot of people working within each facet of the project, but you need to have an understanding of it all.

Screen graphics for Passengers. Courtesy of James Brocklebank.

Continue reading »

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()