The last decade has seen a surge of interest in exploring holographic interfaces in major sci-fi movie productions. Anna Fraser is at the forefront of this wave, and you can see her work in “Ironman 3”, “The Hunger Games: Catching Fire” and “Insurgent”. In this interview she talks about what goes into creating holographic interfaces, from the initial exploration to subsequent collaboration with multiple departments, working within the post-production constraints of existing actor movements and eye-lines, her love of a strong grid and minimalistic, retro-futuristic interfaces, how people see and perceive color, and how the screen graphics work fits into the much larger flow of story-telling on the big screen. In the last part of the interview Anna talks about the evolution of technology on-screen as well as in real life, advances in virtual reality hardware and software, their possible implications on the fabric of our social interactions, and how, despite all the changes in the world of digital tools, the art of story-telling transcends technology boundaries.

Kirill: Please tell us about yourself and your professional path so far.

Anna: My name is Anna Fraser and I live in Sydney, Australia, which is a long way away from America where these things are made.

If we’re talking about screen graphics and holograms, I ended up doing them kind of by accident. I originally studied visual arts, and I had a child when I was quite young. I was making art and having small exhibitions of bronze-cast sculptures and other things, but I couldn’t make any money. I had always liked movies so I decided to become a director [laughs]. Somehow I thought it was going to make me money; I’m not sure what I was thinking.

I went back to university and I did a communications degree in film, media and writing. A sort of a broad postgraduate, and then I started making short films. I then went to the Australian Film, Television and Radio School, which is one of Australia’s best film school. Everybody knew that once you got into the Film School, they would give you money to make films. You also didn’t have to pay money to go there, so I thought it was a great idea. I wanted to do directing, and that was hard to get into. It was very competitive, so the back door into it was to do another subject. I did digital media back then, around 2000, when it was starting to take off. I studied titles design, because I always loved graphics and text, and I was working doing part-time jobs in outdoor advertising and billboard art, which was very boring but functional in earning money. I still thought that I’d earn money being a director. I made some short films and they all had titles and graphics in them but they weren’t straight visual effects and they weren’t straight live action, but rather a combination of live action and titles.

I kept making short films and when I graduated I started working as a motion graphic designer as a day job. I thought it would be my day job and I would continue to make films.

Kirill: And that was around time when computers got reasonably powerful and cheap to be able to afford having them as your own personal tool.

Anna: The first films that I’ve made were made on 16mm or 35mm film, but by then you could buy reasonable cameras that weren’t too expensive. I also had a lot of friends that were in the film industry, and you could always beg or borrow some ridiculous gear that you couldn’t afford.

Kirill: Back then you didn’t have the variety of digital cameras and tools available these days. It must have been more expensive to be an indie filmmaker 10-15 years ago.

Anna: I was working as a motion graphics designer and trying to make films and also being a parent. It was very expensive. You could often get good deals, but I spent an awful lot of money on films, which is silly really. Something had to give. So I decided, and I found it quite hard at the time, to not be a Director anymore, and just be a Designer. The Designer road is a hard enough in itself, and since I didn’t come from a traditional design background, I did a lot of learning on the job. I had all the formal qualifications of creating ideas and images, balance, shape, form etc. but it took me quite a while to understand the communication aspect of design. I made a lot of mistakes [laughs].

Kirill: Lucky for you there’s a lot of people on the production around you.

Anna: At that stage I was working in television, print and advertising, and I made quite big mistakes but I had good friends who, in one instance, did work out jobs for me and literally saved me. But I learned from them, and I learned from all the people around me.

I started doing a lot of freelance work for a company called Fuel VFX in Sydney. I worked for them on and off for quite a long time and I was getting better at being a Designer. I love film and the storytelling side of it, and fortunately for me Fuel was working on VFX [visual effects] and design for films. I mostly worked with Paul Butterworth who was one of the Founders & Directors at Fuel. He comes from a solid art and film training background as well and I found that it was good to work with him. I still work with him on all my film projects; he’s my main VFX supervisor and my main team member that I work with or for.

Continue reading »

What a year has it been for Territory Studio and its founder David Sheldon-Hicks. It’s only been nine months since our interview about the studio’s screen graphics work on “Prometheus” and “Guardians of the Galaxy”, and in the meantime Territory’s work has graced the big screens on three major motion pictures! In this interview David talks about exploring the technical and human aspects of advances in the field of artificial intelligence in “Ex Machina“, the futuristic interfaces of the alien universe of “Jupiter Ascending” and the vast screen graphics canvas of “Avengers: Age of Ultron“. He touches on the collaboration with directors and production designers to distill and refine the visual language of the interfaces, the process of rapid prototyping in the pre-production phase and the tight back-and-forth adjustments of on-set playback sequences, and the technical aspects of projecting interface sequences on translucent glass screens. In the last part of the interview David takes a deep dive into the world of virtual reality interfaces, ranging from enhancing cinematic experiences to better leverage of content in our everyday work and leisure scenarios.

Kirill: Last time we spoke about your studio and its earlier work. And in the meantime you’ve had Jupiter Ascending, Ex Machina and Avengers: Age of Ultron come out, with a lot of work that you’ve contributed to these productions. And on top of that, you’ve started exploring the world of virtual reality.

David: We actually worked on Jupiter Ascending a year prior to that interview. The project took a while to come out (6 Feb 2015) so we haven’t been able to talk about it up until more recently.

Kirill: How does it feel that you have this pile of work that you’re sitting on and can’t tell anybody about?

David: In some ways it’s really frustrating, especially for the people in the studio who have worked on it. But, we’ve all signed NDAs, and don’t want to ruin it for the fans by saying something that might spoil the story.

Yet, it is quite nice to have a bit of time to prepare our portfolio and showcase, to fully do it justice in terms of the story behind all the work. When you’ve just finished a film, you’re so exhausted and still in that space. Sometimes it’s hard to look at the project objectively and fully appreciate all of the thinking and the ideas that went into it. When you have space and time – around six months or so ideally – you get enough distance to join up the dots between the deliberate and intuitive.

This gets really interesting when it comes to our approach to technology in a film like Avengers. By reflecting on how the script and story points influenced our research, we can sometimes see how quickly perceptions and expectations around innovations evolve.

Looking back we can see how public opinion regarded a piece of technology at the moment we were making the film, and how it changed over the 6 or 12 months leading up to it’s release – and hopefully we’re not behind technology!

Kirill: Does it worry you that the world of consumer technology is evolving so rapidly around us in that regard? Can your work quickly become outdated?

David: As a user, yes, because it’s hard to keep up sometimes. But as far as the work being outdated, in some ways we have to celebrate that. We play on the fact that it’s a film of the moment that reflects the cultural experiences of that point in time. It’s not just about the technology, but also about what the technology says about us as a culture. And I’ve always loved that about unashamedly 80s movies. For example, the idea of hoverboards in “Back to the Future” reflected our cultural expectations that skateboarding, so huge at the time, would exist in the future.

So the idea of a date stamp is not such a bad thing. If a film does date because of its views on technology, it can be quite enjoyable. And there’s an element of nostalgia in that, perhaps ten years into the future. You look back on it with fondness the same way you’ll look back at your current iPhone 5/6 when you’re holding your new iPhone 20 or whatever it might be.

Of course, there are other ways to explore technology and different films date in different ways.

In Ex Machina, Alex Garland [writer and director] was more interested in near-future thinking rather than techno-fantasy. He had done a lot of research around AI for the film to keep the story grounded, and we also undertook a lot of research into UI and UX in terms of where the technology is going. So our work in that film reflects the evolution of user experience towards simplicity, personalisation and ease of access, while it also reflects the narrative layers in the story.

Embedded just underneath the lovely uncluttered UI is access to programming code: we wanted it to feel that Nathan had created this OS for the benefit of the public, yet always kept close to the code, and could easily access and manipulate it.

BlueBook office browser software in Ex Machina. Courtesy of Territory Studio.

So, while the work that we delivered made a loose statement on where UI and UX are going, it was also a technological window into narratives playing out around the film – a narrative device for the characters to monitor the activities around the building, for example.

I’m sure Ex Machina will date in a slightly different way other films of that genre because its focus is not to comment on future technology and it’s not tying itself into the cultural zeitgeist in terms of style. As a film about the thinking around AI and our relationship to technology at this time, it’s less a statement about aesthetics and more of a timeless piece.

Ex Machina screens still. Courtesy of Territory Studio.

Continue reading »

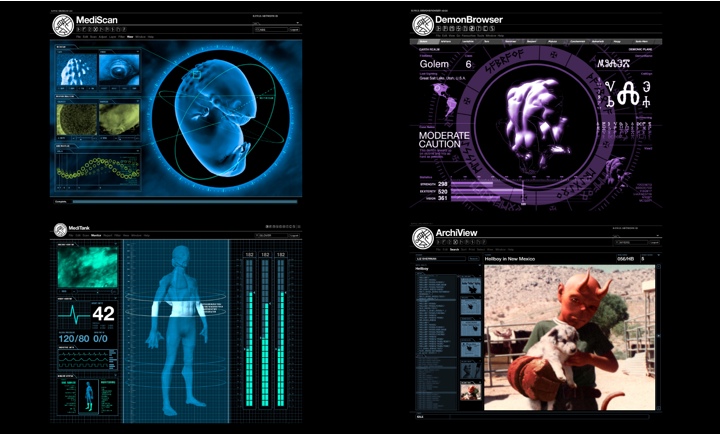

At the intersection of art and technology, the ever-increasing importance of screen graphics in feature film reflects the expanding arc of human-computer interaction in our everyday lives and the pervasive presence of glass screens around us. It gives me great pleasure to welcome Andrew Booth of BLIND LTD to the ongoing series of interviews with designers and artists that bring user interfaces and graphics to the big screens. In the last few years you’ve seen their work on the “The Dark Knight” trilogy, “Hellboy”, “Skyfall”, “Jack Ryan” and the recently released “Kingsman: The Secret Service”, as well as in the cinematic trailers for the CRYSIS game franchise. In this interview Andrew talks about what drew him into the industry, the overall collaboration process within the feature production environment, approaching the technology world of Bond and Batman franchises to define the look and feel of the interfaces, constructing the visual language of the two competing factions in “Kingsman”, the primary goal of supporting the story and the effect it has on all aspects of the craft of screen graphics, and the two-way flow of ideas between the worlds of “fantasy” and “real” screens.

Kirill: Please tell us about yourself and how you got into the field of screen graphics for film.

Andrew: I love film and I love design, and it seemed a natural fit. I come from art and design background, and I like making things. It was good expressive way of doing something that was innovative and thought provoking.

Kirill: It would be a rather boring movie if all the technology it showed you would already be present in your life.

Andrew: I figure with screen graphics you want to see something that has a bit of escapism, excitement and drama about it.

Kirill: Does that get pushed by the director, the production designer and by yourself?

Andrew: Generally it’s all about the story, and within that you will have the graphical element that’s written on the page. Part of your work is reading the script, getting some ideas and then developing them.

As far as who we collaborate with? Generally speaking I deal directly with the director. We also work in conjunction and in collaboration with the art department and the visual effects supervisor.

One of the things that we do at BLIND, which is quite different from other agencies, is that we deal with graphics on set and in post.

The first film I ever worked on was “Die Another Day”. I wanted to get into films and ended up almost breaking into Pinewood Studios to visit the VFX supervisor at the time. I showed the work that I produced including a number of film specific test shots. I think the VFX supervisor was surprised that I got through the gates. Two weeks later I got a phone call and told that they had some post graphics work for me to do. That was my “in” to the industry.

Post is a very different animal compared to on set. You’re working to a specific cut length, and you might only have 12 frames to tell your story graphically.

My second job was for Guillermo Del Toro’s “Hellboy” where everything was live and on set. We had to be very diligent in the way we told the story.

Back to your question, at BLIND we collaborate with the production designer, the VFX supervisor and the director.

UI Screen graphics from Hellboy / http://www.blindltd.com/hellboy / Courtesy of BLIND LTD

Kirill: And that’s where the decision between doing things on set or in post production is made? Some directors would want to see more stuff directly in camera.

Andrew: It is cyclical.

On “Hellboy” “Sahara” “Batman Begins” “Doom” “Casino Royale” “The Dark Knight” our work had predominantly been on set. Then there was a step change where everyone moved away from doing it practically. I wondered if this part of the industry was dying away. Obviously it is easy to green everything up and then think about it afterwards, however with “The Dark Knight Rises” and “Skyfall” there was a return to the practicality of doing as much as you possibly can on set.

As we speak we’re doing an on set project with the VFX supervisor who got us involved in the post-production screen graphics for “Jack Ryan: Shadow Recruit”. We both know that we’re going to do things in post, but we’re trying to achieve as much as possible live.

It’s an interesting hybrid in terms of where we sit.

UI Screen graphics from Jack Ryan: Shadow Recruit / http://www.blindltd.com/jack-ryan / Courtesy of BLIND LTD

Continue reading »

Continuing the series of interviews with designers and artists that bring user interfaces and graphics to the big screens, today’s I’m excited to welcome Corey Bramall. His work spans multiple films and TV shows, from Caprica and Human Target on the small screen to Thor, Captain America: The Winter Soldier, Safe House, the first two G.I. Joe and the last three Transformers movies on the big screen – just to name a few. In this interview Corey talks about the changes his field has undergone in the last 15 years, differences between TV and feature productions, working on multiple movies in the Marvel and the Transformers franchises and striking the balance between the technical nature of real-world computers and making appealing visuals for the aesthetic purposes of the overall production.

Kirill: Please tell us about yourself and what you do.

Kirill: Please tell us about yourself and what you do.

Corey: My name is Corey Bramall, I design and animate the graphics that are on computer screens in movies and tv shows known now as FUI (fictional or fantasy user interfaces). I have been doing this kind of work for around 15 years. I try to balance my life between family, work and play. When I’m not working I’m usually hanging out with my family or going to see live music.

Kirill: What drew you into the field of screen graphics, and how has that changed in the last 15 years or so of doing it?

Corey: I always had an interest in graphics, photography and computers so in high school I got on the yearbook design committee and was playing around with Photoshop 3… “now with layers!” and I remember thinking to myself “this is something.. I’m not sure what, but it’s something”. After high school I was working odd jobs and trying to figure out what I was going to do with my life but I could never shake how fun and creative this program called Photoshop was so eventually I found a two year multimedia program here in Vancouver that offered a variety of classes like ‘Interactive Authoring’, ‘Video Production’, ‘3D Animation’ and… ‘Photoshop’. After graduating the two year program in 1999 I was trained to make CD-Rom titles which of course had gone completely obsolete. I had no industry but I had this odd array of skills that made me sort of a ‘jack of all trades’.

I had found a job at a company that produced terrible course ware for educational training and was about to call it a career at 21 when I got a call from a studio asking if I was available immediately to come and work with them to make graphics for a tv show. I took the job and the rest is sort of history. I worked at that studio for a few years and eventually started Decca Digital. One of the biggest changes in the last 15 years I would say is what’s capable technically. When I started everything was 640×480 pixels and I could backup an entire months work on a single CD. Today most of the stuff I design is full HD (1920×1080 pixels) and can be almost 2GB for just one screen. The other biggest change is just the sheer number of people designing FUI screens.

Kirill: Who do you work for during the various stages of a production, from the initial explorations during the pre-productions all the way to the post-production?

Corey: A lot of my work happens during production where I’ll create graphics to be shot in a scene so they actually have to function in a rudimentary way. I’ll build them so the onset operators can turn widows on and off, move the widows around, change backgrounds and so on. This is an interesting process because as you’re designing you have to think about how the screen will function as well. It can provide some interesting design limitations that I have to overcome and sometimes re-think. Because replacing what’s on a screen in post-production has become much easier, quicker and cheaper, a lot of times directors want graphics on the screen that they know will be replaced later just so the actor has something to interact with instead of a giant green square. I’ve work on projects were I’ve just done the production graphics, just done post-production graphics for burn-in and I’ve done both.

Kirill: Do you prefer having a full artistic freedom for a project, or a more well-defined direction?

Corey: I don’t think I’ve ever had full artistic freedom on any project, that would be amazing to have that freedom one day. Given a choice, I’d obviously prefer full artistic freedom but a lot of my work in the last few years has been for sequels or for films that take place in a universe that was created prior to me being involved so my challenge has been to stay true to that while perhaps adding some of my own style. I tend to work with a lot of the same people who have a style that they’re accustomed to so I’m often bound to that aesthetic but I’ll always find somewhere to add some personal flare.

Kirill: What are your thoughts on the term “Fantasy UIs”? How well does it capture the essence of what you do?

Corey: I think it’s a good term for this type of work. Before Mark Coleran coined the term FUI we called it all sorts of things: computer playback, screen graphics, screen design and so on. But is it Fictional User Interfaces, Fantasy User Interfaces, Faux User Interfaces? Let’s just say it’s Fantasy, once and for all ok?

Continue reading »

![]()

![]()

![]()