Since the early 1990s Masako Masuda has worked on over 50 movies, including Jurassic Park, Death Becomes Her, Erin Brockovich, A.I., Terminator 3, The Polar Express, Memoirs of a Geisha, The Curious Case of Benjamin Button, Act of Valor and the upcoming 47 Ronin, as well as on TV series Sons Of Tucson, Revenge and House Of Cards. In this interview she talks about the art and craft of set design, the overall structure of a traditional movie art department and what changes it is undergoing these days with increasing presence of digital post-production work, the importance of period and architectural correctness, positive and negative sides of working with various software modelling tools, and the differences between working on movies and TV shows.

Kirill: Please tell us about yourself and how you started in the field.

Kirill: Please tell us about yourself and how you started in the field.

Masako: I have several degrees. The first one was in economics, the second one was in sociology. And when I wanted to break into the film business, I was strongly advised to get an interior design degree, so I did.

After I got my third degree I became an interior designer in the department store design, because I didn’t know how to break into the film business. When I felt the time was ripe, I started working on non-union shows. It was way before email and cellphones, and I had to make countless cold calls based on whatever leads I got on any non-union shows I heard about. It took me about four years to break into the union. In the union world, there was a certain cycle when business gets so busy that the list of available union people is almost empty. That was the break people like me then got hired. I finally hit one of these high times with the help from a friend who was in the union. One day she called me up and told me to show up for an interview on her show. I dropped everything, ran over there, and got hired. Once you work on a union show for 30 days, you are accepted to become an union member. Thus, I got into the Set Designers Union.

Within Set Designers Union, there is an hierarchy of designers: Junior B, Junior A, Senior, and Senior Lead Set Designer. You have to work a certain numbers of hours to move to the next tier. While I worked my way up the ladder, I also had a chance to get into the Art Directors Union. Set Designers Union and Art Directors Union then were two separate unions. However, years later, they merged into one, and now all Art Department people are in one union – Art Directors Guild.

I was fortunate at the beginning to work with people who were working with Steven Spielberg and Robert Zemeckis. So, even though I was still a very green junior set designer then, I had great opportunities to work on films such as Jurassic Park and Death Becomes Her.

The closing set of “Jurassic Park”.

Kirill: Was it your dream growing up? Why this desire to get into the movie business?

Masako: To tell the truth, it was not my dream (to work in the movie business) when I was a kid growing up in Japan. I didn’t even know that the film business existed, and even when I found out about it, it seemed so foreign to me. However, even to my kid’s eye, whenever I saw American TV shows or films, I felt that there was a big quality difference between Japanese TV show sand films and American ones. Then this TV mini-series called Shogun came to Japan. By total accident I worked as one of the interpreters assigned to the Art Department. Seeing what they did, and how they did so professionally completely changed my life. I always liked art, but never had a chance to go to an art school. But this experience with an American film crew showed me that maybe there would be a career for me to use my talent. I was lucky to be with such professional production designer and the set decorator. When I asked them for their advice, of course, they first tried to discourage me. But when they understood I was serious, they gave me all their support. Once I made up my mind, it became my passion: to go to Hollywood, and break into the film business.

Kirill: And it’s not really a business in which you can count on a steady paycheck.

Masako: No, definitely not, even though we all wish it to be. This business is never for everyone. If you really want a steady job and steady paychecks, you are not going to be happy to be in this “feast or famine” business. There are always ups and downs, and it is highly competitive. But if you have a strong desire to achieve what you want, let it be set design, directing, writing, special effect, and you’re willing to take certain risks, I will say go for it!

Kirill: As you move to a new production, do you need to be physically there? Can you work remotely from your studio?

Masako: Except some occasions for illustrators or storyboard artists, normally we need to be physically in the art department office wherever it is. It is because we need to be in close communication due to the design direction, changes and revisions which can happen hourly or even more frequently.

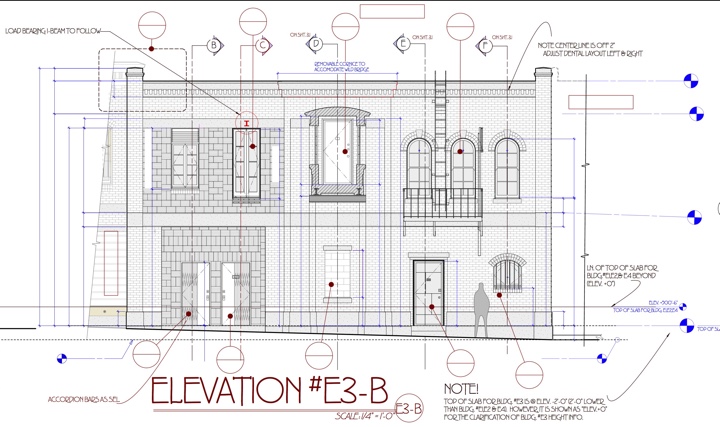

Part of a construction diagram (click for full-size view). Courtesy of Masako Masuda.

Continue reading »

Andrew Lyons is a prolific illustrator with an impressive portfolio that includes client work for GQ, Inc magazine, Penguine Books, BBC, Google and Mercedes-Benz. In this interview Andrew talks about his influences, bringing a human touch to the world of predominantly digital media, the importance of personal work and his recent packaging branding for “Strong” line of nutrient supplements.

Kirill: Tell us about yourself and how you started in the field.

Kirill: Tell us about yourself and how you started in the field.

Andrew: Art was the only thing I was really good at in school, so I knew when I was younger that I wanted to be an artist of some kind. I choose to study painting at university in Cardiff, but when I came out of university I had really now idea what to do with myself, there was no career guidance at all, so I spent the next ten years in odd jobs mostly as a temp working in offices. After a move to France in 2005 I had lots of time on my hands while learning French. I took a graphic design course that taught me how to use Adobe creative suite, but designing logos and websites just felt to restrictive although I liked the aesthetics of clean design. This is when I decided I wanted to be an illustrator, to combine my interest in painting and clean graphics. So in 2010 I started to build a portfolio of personal work and had my first magazine commission 6 months later. From there I just learnt on the job.

Left – illustration for Inc Magazine, right – illustration for Financial Times Weekend newspaper.

Kirill: What informs and shapes your taste and style?

Andrew: So many different things shape our tastes I think, the more the better. I’ve recently realised that the cartoons I watched when I was very small have been an influence, British children’s programmes from the early 80’s like Mr Ben, and Trumpton. I watch these again with my kids and I can see how the visuals were ingrained in my mind, and see similarities with my work which is weird really!

Another big factor is my love for abstract art, and the kind of paintings I used to do in Art school. I was a little obsessed with squares and geometric shapes in flat colours. I admire artists from the St Ives school; Ben Nicholson, Patrick Heron and Barbara Hepworth.

Lastly comic book artists are a big influence, Hergé’s Tintin, and other artists like Yves Chaland, Ted Benoit, Ever Meulen and Joost Swarte. Abstract art and comic books are my big loves. I like the idea of putting comic book style figures into an abstract and geometric background and seeing how they can interact with that space.

Kirill: Do you want to carve out a consistent and recognizable style, or are you willing to push and explore different directions as time goes by?

Andrew: I don’t really try too hard to be consistent. The way in which I draw certain things seems to evolve naturally with time and I can see differences in the work I did two years ago compared to my current work. I so like to try new things, but I take little steps I guess.

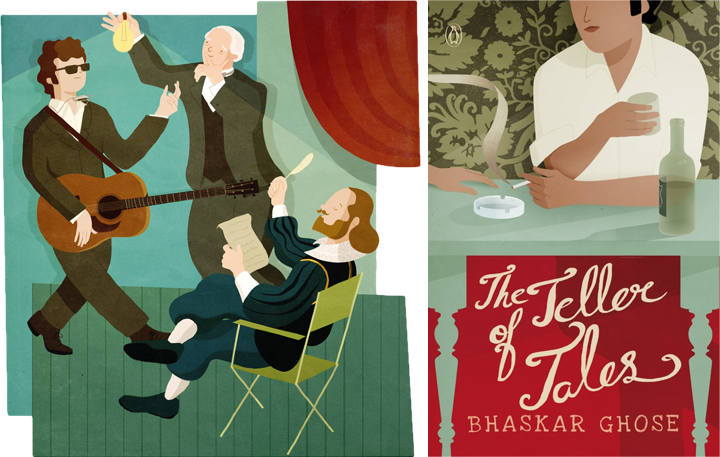

Left – illustration for Spirig AG, right – personal work.

Kirill: Your illustrations are alive with strong human figures, and yet the facial features are reduced to bare minimum. Are you more interested in the shape than in smaller details that might distract from the overall composition?

Andrew: Yes I think that’s probably true, I think it might distract a little, I like simplifying things where I can. But what I like most about having simple features is that it makes the faces more iconic, and possibly easier for people to identify with. Also I like the ambiguity of simple features as it makes emotions difficult pin down exactly, which can be useful when dealing with difficult subjects.

Kirill: As you move from pencil-and-paper sketches to digital outlines and colorizing on computer, do you aim to preserve the imperfection of a human touch? Or is that brought back by textures and lighting?

Andrew: Yes that’s right, I like to conserve some element of the hand drawn in the final art. I’ll either throw in some hand drawn line, or the textures will help to do that a little. More recently I have started to use pencil saying on my characters to rough up their shadows a little, whilst keeping their contours super clean. I like the duality of that. It’s like a push and pull between the right and left side of my brain. There’s a part of me that wants to be Mondrian with super clean lines and colours, and another part of me that just wants to make a mess and throw paint around like Pollock. I try to contain both impulses when I’m working.

Left – illustration for Google’s Think Quarterly, right – cover illustration for “The Teller of Tales” book.

Kirill: How do you preserve colour fidelity when the final product is targeting print media, such as magazines, book covers or packaging labels?

Andrew: I think that it’s difficult to know exactly how the illustrations colours will look once printed as different paper stocks give different results. I work in photoshop in RGB and then covert to CMYK at the end because there are some layer effects that just don’t work in a CMYK file. So when I’m working I’ll click the little ‘proof colours’ option in photoshop to get a rough idea for how it’ll look once printed in CMYK, but apart from that there’s not much else to do.

Kirill: On a related note, you’ve done a lot of editorial illustrations for magazines. Do you see any changes that affect your work as that industry is exploring digital editions and a variety of smaller screens and different form factors?

Andrew: I’ll often supply a layered photoshop document to an editorial client so that it can be animated for the iPad, but I don’t do any animating myself. I know of some illustrators that do the animating themselves so perhaps it’s a useful skill for illustrators to learn these days. But apart from that I’m not sure how things have changed as I’ve not been illustrating long.

Packaging branding for “Strong” line of nutrient supplements.

Kirill: Walk us through the process of creating the packaging branding for “Strong”. How do you capture the essence of an individual product in a single animal, and yet maintain consistency and continuity for the entire line?

Andrew: Thanks, I’m pleased that you think I’ve captured some of the essence of the subject. I start by looking at dozens of photographs and video of the bird in question, and sketching a lot, just drawing the bird as it is to get a feel for it’s shape. Then I sketch again, but this time directly into photoshop where it’s easier to clean up the drawings, and edit them, flip them etc… It’s at this stage that I try to imagine the birds build from clean curves and geometric shapes. I send my drawings to the client for feedback. My Art Director for Strong very honest with her feedback. If something isn’t working she tells me frankly what needs to change, so I go back and redraw, sometimes from scratch until it’s looking right. Working in this way brings out my best work I think as. it doesn’t always look right at the first attempt.

As to consistency, it’s always at the back of my mind when I’m drawing so this comes through in the final work. I use the same textures in almost all the bird illustrations too which helps.

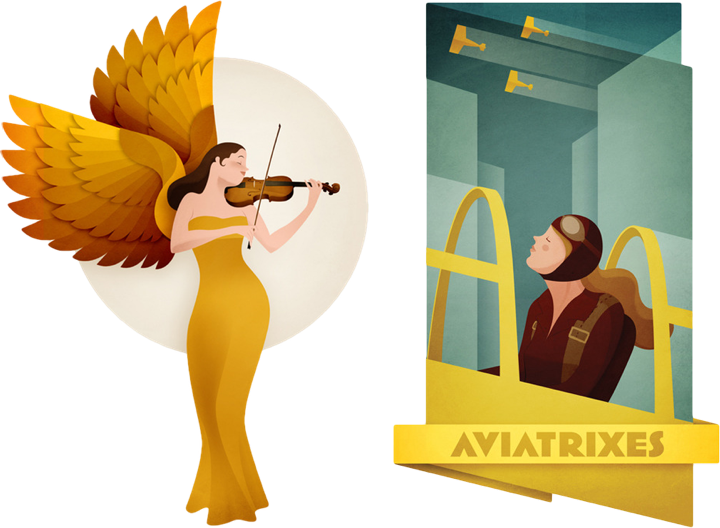

Left – personal illustration, right – personal illustration.

Kirill: What’s the weirdest client feedback that you’ve received so far, if you don’t mind sharing?

Andrew: That’s a difficult question as I’ve never really had any weird client feedback to be honest! The feedback I’ve had from clients is always quite useful. Sometimes the honesty of the feedback can be quite funny, but it’s usually spot on.

Kirill: How important is it to invest time in personal projects?

Andrew: It’s important for me, and my personal illustrations have brought me new work quite often. I sometimes think that personal work has a quality that some client work is missing, there’s a drive and passion behind a lot of personal work, and I can see it myself when looking in other illustrator’s portfolios. The only difficulty with personal work is getting feedback, and being your own critic. I have other illustrators I can speak to to ask their opinions because when you’ve your head in a piece of work, it can be hard to see things that aren’t working. So a fresh pair of eyes really helps.

Personal work is important too for moving my portfolio and style forward.

Illustration for Bspirit magazine.

Kirill: What do you do when you run out of ideas and get stuck?

Andrew: When I get stuck I’ll try and work through it for a time and I’ll keep at it until I just can’t get any further. Then I’ll do something totally different. I’ll take a walk or read a book. And it’s when my mind is elsewhere that the ideas often come. I’ll often use spider diagrams and write down words related to the subject first rather than drawing anything. Then when I’ve filled a page I try connecting words on opposite sides the page to find something unique, a new idea. Then with an idea in mind of what I want to draw, I try to figure out how I’m going to draw it.

If I’m working hard on finding a visual solution before bed, I sometimes wake up with a picture in my head in the morning, so I quickly sketch it down before I forget it. But it’s rarely that easy.

Kirill: What’s the best thing about being an illustrator?

Andrew: Well, my two favourite things about being an illustrator are being able to work from home and spend more time with my wife and kids. And learning about something new with each project, from Iron ore mining in Africa to William Morris.

Illustration for educational textbook.

And here I’d like to thank Andrew Lyons for his wonderful work, and for taking the time to answer a few questions I had about his art and craft. You can find his work online at his main portfolio site and his personal Tumblr stream. Select illustrations are available for sale at the Society6 shop. He’s also active on Behance, Dribbble and Twitter.

Continuing the ongoing series of interview with illustrators, it’s my pleasure to welcome Brian Edward Miller on my blog. Brian is the creative mind behind the Orlin Culture Shop (OCS) based in Erie, Colorado. His evocatively stylistic landscapes and vibrantly energetic human figures are brought to life with bold strokes and strong color palettes. In this interview Brian talks about his roots, his creative process and designing for various media.

Photograph by Brad Edwards.

Kirill: Tell us about yourself and how you started in the field.

Brian: My name is Brian Edward Miller and I’m the owner and illustrator behind Orlin Culture Shop (OCS for short). I got my start as a creative professional in the field of graphic design and worked for a number of different agencies and studios.

Around 2005-2006 I realized that my favorite part about design was illustration, something I leveraged heavily in all of my projects. I made a decision to pursue drawing more seriously in my spare time and was able to shift the course of my career in a way that afforded me more opportunities to draw. I started by showing up to work an hour early so I could draw and stayed up 2 hours later every evening to create. Next, I took jobs which were less taxing creatively and demanded less of my time so I’d have the energy to pour into drawing. Every drawing I did I saw as an opportunity to grow and it helped me to maximize my study and drawing times.

I ended up working at a few gaming studios as a graphic designer with a handful of opportunities to try my hand as a concept artist. It was here I had my first taste of a career involving drawing and I couldn’t get enough of it. I tried a number of times to make the transition from graphic design to concept art, though none of the opportunities worked out because I could make more money as a Senior Graphic Designer or Art Director than I could a Concept Artist – which is a big deal for me as I have a wife and 2 kids!

Eventually, the decision was taken out of my hands as the first game studio I worked for was dismantled and sold, while the other closed down less than a year later. After the studio closures, I decided to put my abilities to the test by venturing out on my own and starting my own business.

Spot illustration of a broken down vehicle.

Kirill: What drove you to start your own studio, and what is behind the “Orlin Culture Shop” name?

Brian: I started my own studio out of an even mix of necessity and opportunity. As I mentioned above, the gaming studio I was working for had gone under just as I was on the cusp of pushing into concept illustration. I was torn as a creative professional because I had more confidence in my skills as a graphic designer, but I was much more passionate about illustration.

After a handful of interviews at other gaming studios out of state, my wife and I decided we didn’t want to leave Colorado. As there were no local gaming studios which fit our search criteria, we decided to create our own studio which would allow me the freedom to work in the industries of my choosing. Thus, Orlin Culture Shop was born!

Behind the Orlin Culture Shop name is the continuation of an artistic legacy which began when I was very young. My grandfather (whose middle name is Orlin), used to have a workshop in his basement where he’d work on a number of different crafts such as leather working, cross stitching, wood working, etc. – all hallmarks of the vintage Americana generation he grew up in. I spent countless hours in that shop dreaming and building (as well as hammering thousands of nails into boards).

When it came time to name my shop, the name Orlin popped into my head and stuck. Its my hope that I’ll be able to contribute artistic works which will have a positive impact on culture, whether its through editorial illustrations or picture books.

Mowrey Manor, illustration for an educational iPad app.

Kirill: What informs and shapes your taste and style?

Brian: My taste and style was shaped by an amalgamation of influences ranging from Vintage Disney, 1980’s cartoons, Manga, Comic Books, 1940-1960’s advertising illustration, and countless picture books. I tend to fixate on mood and atmosphere in the art I love the most which means I appreciate a broad spectrum of styles and approaches, so long as the mood is right.

Kirill: Are you experimenting with illustration elements outside your comfort zone? Is this a constant process of defining and refining your own style?

Brian: There is always a process of defining and refining my own style. I am constantly on the hunt for refinement within my process and there’s still a TON to learn.

One of the greatest things about running my own business is I have the freedom to experiment as much as I want (so long as I’m bringing in paying work of course). I’m no longer tied to a single job title and description which means I’ve been able to work in a number of different industries.

I also find that every project and client has unique requirements which challenge me in ways I’d never willingly challenge myself. There’s lots of growth that happens because of this, and very healthy boundaries set with deadlines to ensure I don’t get too lost exploring.

Kirill: As you start working on a new project, is it pen and paper first, or all-digital?

Brian: When I start working on a new project, its usually a mix of pen and paper first, followed by all digital. I tend to think better on paper where I can quickly write notes and throw down rough lines to get all my ideas out first. From there I’ll head to the digital platform where I do my ‘official’ sketches and final production.

A farm illustration – from the initial sketch to the final look.

Kirill: How do you preserve color fidelity when the final product is targeting print media, such as flyers, posters or magazines?

Brian: Unfortunately, I have very little control over that as most of the clients I’m working with live out of state or out of country. I don’t have opportunities to go on press checks or do anything about quality control so I’m left to the mercy of the client and their chosen printer.

Ideally I’d be able to make the two match but that would require I’m present at every stage of the process. The disparity between print and digital platforms has been something I’ve learned to accept simply because both are so different. I always love pouring over the details of a printed piece, but I also love the dramatic backlighting of a piece viewed on a screen or tablet. I’m comfortable keeping the two distinct which helps keep me appreciate the way a piece shines within different media (as well as keeping me sane).

Peaceful valley scene.

Kirill: How much different is the final illustration from the initial concepts that you’re imagining in your head?

Brian: Most often, the final piece is extremely close to what I had imagined in my head (or at least some evolution of what I was envisioning). I tend to focus my imagination on a mood or a feeling so there’s a lot of latitude and room to explore as I move from initial concept to final illustration while staying true to the original vision. That latitude and room for exploration is important to me because drawing can be very tedious work. If I’m simply retracing steps over and over, I get bored.

What are your thoughts on illustrations for web sites, and how does it scale with responsive design and smaller mobile screens?

I’m so used to seeing my illustrations digitally and on websites (usually my own) that I tend to think of the web as the true home for my work. When I do a piece for a client, I see it on screen for months before finally seeing it in print. This makes the print version “the stranger” who looks vaguely like the person I remember sending off…

As for scaling, I believe strong color palettes, diverse tones, and bold shapes help an illustration to scale well, though there’s always some level of detail that is lost as the image size decreases.

Editorial illustration for 1940’s era Snow Bowl.

Kirill: Do you have a particular inclination towards illustrations of nature?

Brian: I definitely have an inclination towards illustrations of nature. Growing up in Colorado, nature was a part of my childhood as I spent the majority of my time playing outside, enjoying the seasons and outdoors. I was also fascinated with Bob Ross as a kid. I remember watching his show with my dad almost every day (I even tried my hand painting using the kit they sold at Hobby Lobby!)

The funny thing is looking through my sketchbooks from the past, you won’t find any drawing of nature. Its all human figure studies, comic book and cartoon characters, etc. Its only when I started my own business and began to figure out who I was as an artist that the inclination towards illustrations of nature took on a powerful presence in my work.

Kirill: How important is it to invest time in personal projects?

Brian: Personal projects are vital to my ongoing development as an artist. It was only with personal projects that I was able to focus my efforts as an aspiring illustrator. My projects included writing and drawing comics / graphic novels, designing characters for animation pitches, and dreaming up story ideas for picture books. It helped me to learn creative writing, illustration, and forced me to face my weaknesses. It also empowered me to transition an idea from my imagination to the digital canvas.

Illustrations for Tarsus Group’s “Label Expo 2013”.

Kirill: What do you do when you run out of ideas and get stuck?

Brian: There is nothing magic about my approach when I’ve run out of ideas or get stuck. I’m very dependent on deadlines to help drive through insecurities and pride (the two culprits I most often discover when I’m trying to understand why I’m stuck). Deadlines force me to sit down and draw despite the fear or uncertainty I’m experiencing. Its only after I’ve thrown down a few ideas (usually the most generic ideas I can think of, the ones which occur to me first) that I begin to get comfortable with the project, my abilities, and my objectives. I have to move forward no matter how much those first few steps hurt, otherwise I’ll sit and stare at a blank page forever.

Kirill: What’s the best thing about being an illustrator?

Brian: The best thing about being an illustrator is being able to provide for my family in a way that allows me to work from home by creating work I love. I also get to see some of the best parts of being an illustrator through the eyes of my kids. When they get excited about the picture books and illustrations I’m creating, that is always cause for me to be thankful. Its there I realize the headaches that accompany being a small time business owner are worth it simply because I’m living a dream I’ve had since childhood

Villainous robots from the “Totes Adorebots” series.

And here I’d like to thank Brian Edward Miller for answering a few questions I had about his art and craft. You can find Brian online at his portfolio and blog, as well as on Behance and Twitter.

In the last two decades Oana Bogdan has worked on dozens of movie and TV productions. On the big screen her career spans “Stargate”, “Godzilla”, “Vanilla Sky”, “I, Robot”, “Underworld”, “Total Recall” and the upcoming “The Prey”. On the silver screen you have seen the her work in “24”, “Without A Trace”, “Cold Case”, “Criminal Minds”, “Justified”, “Dark Blue” and “Hawaii 5-0”. In this interview she talks about how the craft of art direction and production design is changing in the world of increasing capabilities of digital tools, the shifting balance of responsibilities between the various departments, why building real-scale vehicle models was necessary for “Total Recall” and how different the work like is between movies and TV shows.

Kirill: Please tell us a little bit about yourself.

Kirill: Please tell us a little bit about yourself.

Oana: I was born in Romania and moved to the US when I was 8 years old. I got into the film industry in 1993, I had just moved to LA the year before, and my first project was “Stargate”, the one that Roland Emmerich directed with James Spader and Kurt Russell. The film industry has definitely changed a lot over the last 20 years. At the time, “Stargate” was a pretty big show, and surprisingly, it was a non-union project. It was pretty easy to get into the film business, I think, in those days. I ended up working in the creature department even though my initial contact was in the art department. I had a very nice meeting with the art director, Mark Zuelzke, who then thanked me and told me that he was not going to hire me! He told me to call this other person on the project because he was also looking for some help, and that’s how I ended up in the creature department on that film. The designer and fabricator of the creatures was Patrick Tatopoulos, and I ended up working with him for the next eleven years. He went back and forth between production design work and creature effects work, and I got the chance to work in both of these departments along the way.

Kirill: Looking back to those earlier years, how was the process of bringing creatures to life on film? Did it involve more physical craft than it does today?

Oana: Yes, actually, effects were typically made practical at that time and the majority of the effects we created for the film were practical and in camera. Stargate was revolutionary at the time, we developed a new technology for the visual effects with the stargate ring, where the characters would pass through the ring using an optical effect to get to the parallel world. It looked as if they were passing through a vertical plane of water. We also had helmets that we constructed for the creatures, Anubis and Horus, the guards and Ra that needed to retract back from their faces. We had physical helmets created, and through visual effects morphed them digitally to reveal the heads of the actors. That was the beginning of digital effects as we know them now.

On the set of “I, Robot”

Continue reading »

![]() Kirill: Please tell us about yourself and how you started in the field.

Kirill: Please tell us about yourself and how you started in the field.![]()

![]()