After hitting his stride as the production designer on the TV show “Alias”, Scott Chambliss has risen to the top ranks of major movie productions. In the last few years Scott has worked on “Mission: Impossible III”, “Salt” and”Cowboys & Aliens”. He has also continued his collaboration with the director J.J. Abrams on the reboot of the Star Trek franchise. In this interview Scott talks about the traditional collaborative triumvirate of director, cinematographer and production designer and how that balance is shifting in the world of increasingly VFX-driven sci-fi productions, how advances in digital technology and global connectivity affect the current state of the visual arts, the approach he has taken to bring back the rich world of the original Star Trek universe to the modern audiences, his take on where human-computer interaction should go, and his thoughts on 3D productions.

Kirill: Please tell us a little bit about yourself.

Kirill: Please tell us a little bit about yourself.

Scott: I’m a motion picture production designer, and I’ve also designed episodic television. I began in fine arts and theater design in school, and spent the beginning of my career in New York working on Broadway and regional theatre productions while keeping up on my own artwork, which included showing work gallery shows.

Kirill: Was “Alias” your first big-scale production?

Scott: Not at all. As a matter of fact, “Alias” came along at what I thought was the end of my career. A pause for a professional history recap: I’d done a number of assistant art direction jobs on large scale studio features shot in New York and then designed my own first small feature there, which led me to Los Angeles to try my luck as a full-time production designer. The projects I landed in LA over the next eight years were small features and episodic tv pilots plus a few mid-scale studio comedy features. While I met and continued to work with a handful of wonderful directors, producers, and other creative collaborators, none of those projects ever built real momentum for my career. They were all virtually invisible to the public as there was not an attention grabber or a box office hit in the bunch. By the time the “Alias” pilot rolled around I had resigned myself to the fact that I was probably in the last days of my efforts to be a production designer and was seriously exploring what else I might do for a living. I was still a young guy with a future to create, so maybe it was time to begin Act Two.

What I imagined to be my last gig in the biz, taking over the tv episodic “Felicity” in its third season, (when it was no longer even being tracked by the Nielson ratings because its viewership was so miniscule), unexpectedly turned into my game-changer. This job brought me into the same room with J.J. Abrams at a somewhat formative moment in his career, and we hit it off creatively and personally. Toward the end of that season of “Felicity”, JJ liked my work and how I did it, and he asked me if I’d do the new pilot “Alias” he’d just written and was going to direct. That pilot was the beginning of a creative relationship that I’d always hoped to have: mutually inspiring, always supportive, adventuresome to the point of riskiness, fueled by respect for the talents of each other. It’s more than ten years later, and I remain devoted to our working process together and grateful for any opportunity I have to work with J.J.

Kirill: People usually talk about the director, the cinematographer and the production designer as the trio in charge of defining the universe, the visual look and the atmosphere of the specific movie. Are you looking to be on the same brain wave length with your collaborators, or for more of a clash of different ideas?

Scott: The clash part of a job…or in life, for that matter… is not inspiring to me. I think there can be any number of different points of view on the piece of material that you’re collaborating on, and they’re each a necessary part of the collaborative discussion. However being rigid with a point of view is a rather limiting stance. There are many ways to tell a story, and the task of exploring approaches that aren’t your own is an interesting process. When there’s a mutual respect among the storytelling collaborators on a film, very nuanced tales evolve which are richer than a story any one of us would come up with on our own. The kind of team I am most at home with understands and supports this point of view. I know that’s not the way every film making collective in town works, and I’m well aware that some directors prefer a confrontational dynamic in their work environment. Having worked in a few of those situations myself, I’ve found that such an atmosphere to be anti-creative.

Left – on the set of “Mission: Impossible III”, photography: Scott Chambliss, courtesy Paramount Pictures. Right – on the set of “Cowboys & Aliens”, photography: Zade Rosenthal, courtesy Universal Pictures.

Continue reading »

Continuing the ongoing series of interviews with creative artists working on various aspects of movie and TV productions, today I’m pleased to welcome Leslie Morales. In this interview Leslie talks about the art and craft of set decoration, why Oscars are awarded to the team of production designer and set decorator, the differences between working on TV series and movie productions, and her work on the recently released movie “Stoker“.

Kirill: Please tell us about yourself and how you started in the industry.

Leslie: My name is Leslie Morales and I’m a set decorator. I started as a starving artist / painter. I had a painting studio in Santa Monica and like most artists, I was looking for odd jobs to pay the rent. I started scenic painting and then costuming, and very quickly ended up decorating a film, probably within a year or so. Years before that I had considered being an actress, and decorating to me fit that profile – reading a script and creating a character. This is how I saw set decorating – between acting and painting.

I never studied – or even considered – set decoration in that it would be my career. I learned from directors, production designers & the directors of photography which I thought at the time was all fascinating, guess it was sort of a self taught process. On my first job I had no idea what a decorator did, and I’m glad that I learned that way. It was intense & crazy & fun.

Kirill: When you are considered for a job, is there any kind of process where people look at formal education? Or perhaps after a few productions it matters much less and they look at your body of work?

Leslie: For me the educational background doesn’t seem to matter. It’s far more what you’ve actually done on film. If someone’s interviewing me for a show, they know my eye and my style, they know the directors & production designers I worked with, and that’s where it’s coming from. For most decorators that I’m aware of, it has much more to do with the work that you’ve done than any specific education that you have, though I think a fine art background is very helpful. I’m not sure that there’s much educational curriculum geared to film art. You look at film schools and their focus is on writing, directing, photography and acting – all very important but you don’t see many courses on production design or decoration.

Kirill: What’s your role in the overall structure of the art department? I’m looking at the list of nominees for the Oscar awards for production design, and it’s always the team of the production designer and the set decorator. What makes this relationship so special?

Leslie: We’re considered the visual heads of the art department. The way I see it, the designer – along with the director – will create the overall visual design of the film. For example, “Stoker” had a very specific color palette, with a distinct symbolism defined by the director Chan-wook Park. So Thérèse DePrez (production designer) and I, or any designer and set decorator, start the dialog on how you take that conceptual discussion to screen. The designer is always the creative head of the art department, and the decorator would be, I guess, the next creative head. Ideally it is a very collaborative effort. We’re constantly having discussions, building our canvas on screen, talking to the director & the director of photography clarifying the mood and the texture of each set.

The art department has many people from art directors, set designers, painters, construction & props. And in my department I am supported by my lead person, my buyer & set dressers. We, the production designer & the set decorator are the two people who are responsible for getting the look on film.

Continue reading »

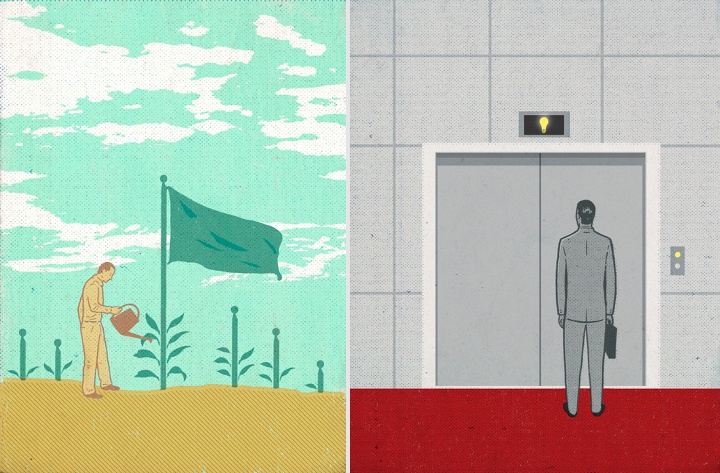

Continuing the ongoing series of interviews with illustrators, it is my pleasure to welcome the talented Dan Page. Dan’s editorial portfolio includes clients such as Time, The Washington Post, The Boston Globe, Forbes, Reader’s Digest and many others. Every illustration packs a powerful twist, with a unique, strong and expressive visual delivery. In addition to his extensive editorial work Dan has also illustrated a number of book covers, most prominently for the Vinyl Cafe series.

Kirill: Tell us about yourself and how you started in the field.

Kirill: Tell us about yourself and how you started in the field.

Dan: I grew up in the suburbs of Toronto and went the regular route to be an illustrator. I had artistic talent growing up, went to art school (Ontario College of Art and Design), but never imagined an Illustration career at the time. Like many students, I simply gravitated towards Illustration from all the options art school had to offer. The course that hooked me was a third year Editorial Illustration class, taught by the late Jerzy Kolacz, an immigrant from Poland, and a respected conceptual Illustrator. Jerzy had a way about him, a master at crafting ideas, and inspiring students to think conceptually.

Kirill: What informs and shapes your taste and style?

Dan: My work is shaped by communicating ideas through images. I like to take a graphic approach. I love a good line drawing, playing with different textures or even now silhouetted shapes.

Distilling things down and not overloading a composition gives me the end result I’m striving for.

Kirill: Do you want to carve out a consistent and recognizable style, or are you willing to push and explore different directions as time goes by?

Dan: I love to explore and push things, it keeps things fresh and exciting for me. Exploring new techniques new possible ways to complete a final has become part of my process.

With technology you can make a few different finals up to the last minute of a deadline. This was not possible a decade ago, at least the way I would work back then. You needed to be sure of how you would approach a final with little wiggle room for changes. I’ve been Illustrating full time for over 20 years.

I know from personal experience that without pushing and exploring, surviving a long career is difficult. Creating new ways of approaching assignments is reenergizing. It makes work feel less like work.

Kirill: Your editorial illustrations seem to be about distilling the main subject into a single, powerful, thought-provoking idea. Is there any sort of organized process behind this, or more of a sudden bolt of inspiration?

Dan: Coming up with original ideas is the most challenging and difficult part of my process, but also the most rewarding. I wish it was easier since it’s always done under time constraints – the all powerful deadline.

It’s an unpredictable process. While I’ve experienced the gift of a sudden bolt of inspiration, I would never bank on it, but every day I hope for it! It’s usually old fashioned hard work and not organized at all. it could be a sketching process, researching subject matter, google searches, calling friends for insight, taking a break, taking a drive, grabbing another coffee, taking a shower, looking up past sketches… and then the a-ha moment! Immersing myself in the subject matter visually and intellectually, letting it soak in consciously and sub-consciously would best sum up this process.

Kirill: What’s the technical process? Pen-and-paper first, and then transition to digital tools?

Dan: Yes, pen and paper then scanning things into Photoshop, that’s the general rule. Along the way I may have an idea for something new to try. The technical end is the more predictable part of the process. I enjoy both the traditional and digital parts of this process equally, the combination of the two offer endless possibilities. I remember when my process was all traditional from start to finish. In retrospect creating art work then wasn’t as exciting compared to incorporating the digital element in my current work. This additional element eliminates the monotony of the process. Its like driving somewhere and taking the same route every time. I find that the digital process takes you on new interesting twists and turns all the time, yet arriving at the same destination.

Kirill: Once the magazine is published, do you ever wish to go back and tweak that illustration? Has it ever happened that you had what seemed to be an even better idea after the process has been completed?

Dan: Absolutely, I’m not satisfied with everything I’ve done. With all the different variables involved when an assignment is underway, the stars don’t always align. There is a collaborative element to illustration. My sketches have to be approved by Art Directors and Editors and my preferred idea may not be the one approved by the AD / Editor for whatever reason. You just proceed, and that’s part of the job. Getting a second and third set of eyes involved in the process can improve my ideas as well. I am flexible and have benefited from great art direction many times.

Kirill: How different is it for you working on book covers? How do you approach capturing a larger story in a single illustration?

Dan: It does feel different when working on a book cover, but I try to remind myself that it’s not. There is a throw away aspect to magazine illustration, if you do a bad illustration, it will be gone the next week or the next month.

Not with book covers, you put more pressure on yourself thinking they will be around for a real long time – you don’t want to screw it up. Plus, that feeling carries over to the book publishers, this is their baby you are working on, you can sense it in all your communications with the Art Directors. They want to make sure it’s just right. I try to just focus and keep doing my thing. I do find reading the whole book helps in the process, rather than working from a synopsis. On the other hand, I’ve done a number of covers for the author Stuart McLean and he’d rather I create an intriguing image that may compliment the title without reading the books or knowing anything about them. This has been very successful as well.

Kirill: How do you preserve color fidelity when the final product is targeting print media, such as magazines or book covers?

Dan: Amazingly what I see on my iMac usually is translated to print, whether they are RGB or CMYK files, it always seems to print without problems. I don’t have to do anything special to preserve it.

Kirill: You’ve done a lot of work for what used to be traditional print media. Do you see any changes that affect your work as the magazine and book publishers are exploring digital editions and a variety of smaller screens and different form factors?

Dan: I keep hearing there may be changes, I’m sure there will be but it hasn’t impacted my work at this point. I remember what I was doing when they announced on CNN that Newsweek is going all digital. It hit me that times were changing. I don’t foresee it affecting work flow, as media still will need graphics in some shape or form. I have done some assignments for digital use only, it seems like the transition is a slow process, giving graphic artists time to adapt along the way. But as for now, print is not dead.

Kirill: What’s the weirdest client feedback that you’ve received so far, if you don’t mind sharing?

Dan: It involves one of the most famous magazines on the planet and one of the most famous editors. It ended with a kill fee. I tried to push the boundaries a little and found out that there is an actual line that you can cross.

I thought I’d never work for them again, but I’ve worked for them recently. I guess I didn’t go too far over the line.

Kirill: What do you think looking back at your own work from a few years ago?

Dan: There’s an evolution that takes place. I always want to go forward and try new things and feel like my work is changing and growing, but deep down you want it to be better than before. That is difficult to do.

Kirill: How important is it to invest time in personal projects?

Dan: It’s good to break away from the regular routine and structure of making images. You can find a new technique or explore subject matter that you’ve always wanted to do but never get the chance.

Personal projects can elevate your work as you usually delve into subject matter that is close to your heart. This is probably when you can get the opportunity to do your best work, so it’s very important.

Kirill: What do you do when you run out of ideas and get stuck?

Dan: I may have already touched on this when I discussed my process. I get stuck all the time. Having a deadline surely helps, sometimes having a shorter amount of time in a deadline gets ideas flowing more.

There must be a psychological reason for this. I’ve been through experiences where I’d send in a set of sketches where I racked my brain, turning over every stone… only for all the sketches to get rejected.

You get asked for more ideas, and you think to yourself that there are no ideas left, I’ve thought of absolutely everything! Instead I say, OK I’ll see what I can do… and surprisingly I end up nailing it with something unexpected right at the last minute. PHEW.

Kirill: What’s the best thing about being an illustrator?

Dan: The best thing is that you are making art every day – it doesn’t feel like work.

And here I’d like to thank Dan Page for taking the time to answer a few questions I had about his craft. You can find more of Dan’s work on his main portfolio site and his agency page. All illustrations used with the author’s permission.

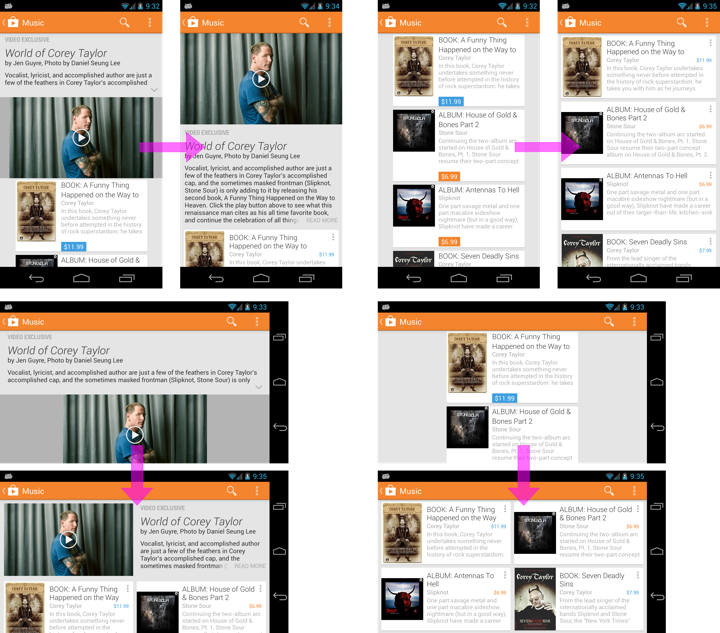

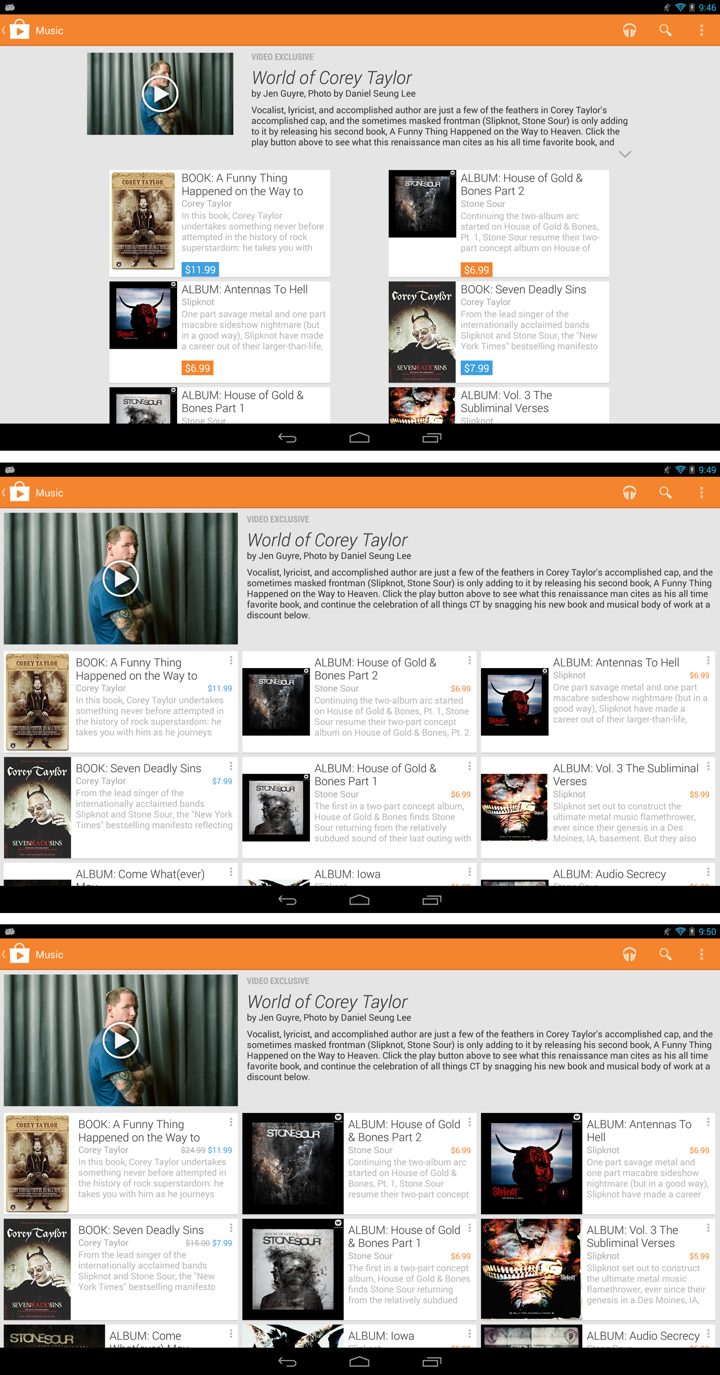

This hasn’t strictly happened in the latest release of Play Store, but worth mentioning nonetheless. The screenshots below show the layout changes made in Play Store 4.1 for editorial pages.

The header underwent quite a few layout changes. In a single-column mode we swapped the description and the video to result in a more pleasing aesthetic flow that begins at the top of the page. The rather random 2-line collapsed description has been replaced to have the description section have the same height as the video element. The video element itself is a fixed 16×9 block that goes edge-to-edge with no unsightly gray pillar bars. Finally, the last few characters of the last line in collapsed description are faded out with superimposed “read more”, removing the rather awkward dangling arrow caret that we used to have.

In landscape mode the header goes to two columns – video element on the left and description on the right. The description is limited to show as many lines as possible without vertically overflowing the video element.

Card content underwent grid alignment as well. In portrait mode the cards go edge-to-edge with consistent visual and layout treatment of the price element. We’ve also tightened up the line spacing of two-line titles and went to two-column layout in landscape mode. Pretty much all pillar bar margins are gone, resulting in a better defined grid and a better usage of available screen estate.

For these screenshots I purposefully chosen an editorial collection that mixes items from various media types. Such collections present an interesting design challenge to balance the exposure of cover art with grid alignment. Cover art for apps, albums, TV shows and movies is fixed aspect ratio (1×1 for the first three, around 1.441×1 for the movies). Books and magazines are mostly in 1.35×1-1.52×1 range, but there is significant variation in some of the genres, particularly children’s books. When you have a collection of items with varying aspect ratio of cover art, what gets aligned?

Our current approach is to have two fixed aspect ratios – 1×1 for apps, music and TV shows and 1.441×1 for everything else. The second aspect ratio is a perfect fit for movies, and lies rather conveniently in the middle of the “regular” range for books and magazines. If you browse those sections in the Play Store you will notice that the covers go edge-to-edge along one axis (vertical or horizontal) with white space on the sides along the other axis.

Mixed content in the same collection (such as editorials, wishlist or recommendations) presents another problem that can be seen in this screenshot:

For aesthetic and alignment reasons all cards in the editorial collections have the same height. What happens when you have items of mixed aspect ratio? Our previous approach was to allocate fixed width and vertically center the cover “asking” it to fill as much of that width as possible. It resulted in a rather unbalanced look of cards for items with 1×1 aspect ratio – such as albums in this specific collection.

In the latest release of Play Store we have revisited this approach. The cards still have the same height, but the allocated width depends on the actual type of the specific item. Movies, books and magazines continue getting the width based on 1.441×1 aspect ratio. Apps, albums and TV shows, however, get more width for their cover art – based on the 1×1 aspect ratio. This results in a much more prominent space given to the cover art. As with every design decision, when something gets more space, something gets less. In this case, there’s less horizontal space available to the title and the item description. The title might go from one line to two lines (or even get cut off). In addition, we no longer have a single vertical line that has all titles, subtitles and descriptions aligned to it. Instead, we might end up in something of a zigzag that has its shape defined by the sequence of items within that collection. That is a conscious tradeoff in this decision.

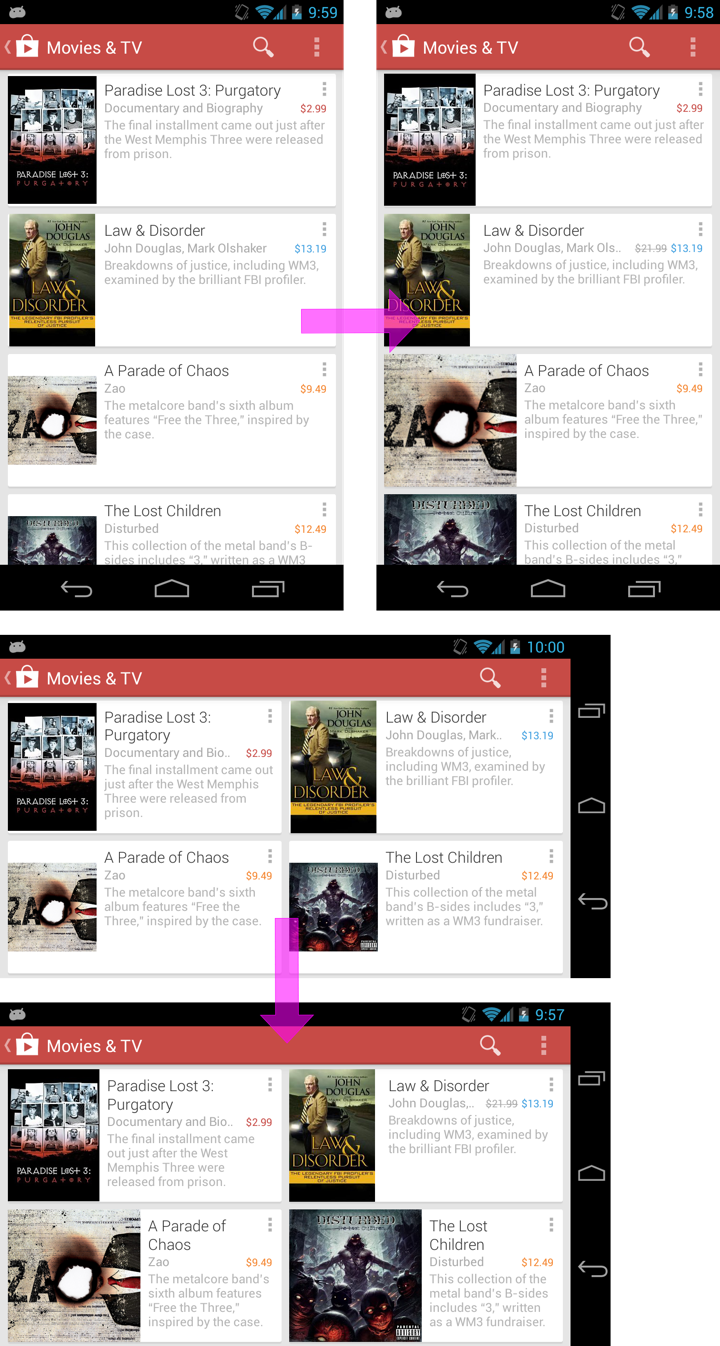

And while up until now I’ve talked about portrait and landscape phones, it doesn’t mean that we forgot about larger devices. If anything, the positioning of the different elements used to be even more random on those devices. The screenshots below show the changes that were made to impose a consistent grid that enforces structure and flow on the editorial collections.

One of my favorites here is how the card grid columns “extend” into the header, forcing the video element to be positioned edge-to-edge in the first column. And, with more horizontal space to give to the header description, this particular one has just enough space to show the full description without the need to go to “read more” collapsed mode.

![]() Kirill: Please tell us a little bit about yourself.

Kirill: Please tell us a little bit about yourself.![]()