Continuing the ongoing series of interviews on fantasy user interfaces, it’s my honor to welcome Jamie McCallen. In this interview he talks about keeping the viewers in the story, the process of designing for screens in film, the differences between on-set and post production work, and the evolution of hardware and software tools at his disposal. In between and around, Jamie dives deeper into the first 15 years of his work that spanned productions as diverse as “Elysium” and “The Age of Adaline”, “Batman v Superman” and “Night at the Museum: Battle of the Smithsonian”, “Star Trek: Beyond” and “Godzilla”, and many more, including his most recent work on “Altered Carbon”, “Skyscraper” and “The Cloverfield Paradox”.

Kirill: Please tell us about yourself and the path that took you to doing screen graphics in film / TV.

Jamie: I am a freelance designer and developer based in Vancouver, Canada. Over the last 15 years, I have worked on just over 40 film and television productions providing interactive desktop and mobile applications and post-production motion graphics.

I took a bit of a detour before getting into the industry. Art and programming had been interests, but I always had a different career in mind. In my teens, I had had art lessons, attended summer computer camps, that sort of thing. In my first years at university, I had taken a few programming courses and I worked one summer developing research applications for a statistics professor. But my intended career path was law and labour relations and over the next few years that’s what I did: law school, human resources manager, lawyer, co-founder of a labour relations non-profit organization. To that point, I had enjoyed the work I was doing, but it was while building the website for the non-profit, that something clicked. I realized I was excited about what I was doing and really enjoyed the combination of coding and design. Not wanting to give that up, I started working with a Vancouver-based team building websites for game companies and their game titles.

Around this time, I had a chance encounter with Rick Lupton, owner of i.Solve, Inc. Rick had heard I was doing some work in Director and inquired if I could build a joystick-controlled gimbal screen for the x-jet in “X2: X-Men United”. Over the next few years, I worked with the i.Solve group and started to design more and more screens.

It would take a few more productions and the opportunity to work with Gladys Tong and the G Creative team before I stopped thinking of myself primarily as a developer and started to consider myself a hyphenate (designer-developer).

Screen graphics for “Godzilla” under the creative direction of G Creative. Courtesy of Jamie McCallen and Warner Bros.

Kirill: Looking back at your first couple of productions, what was the most unexpected part of working in film?

Jamie: On the first couple of films I worked on, I remember chasing some information that I thought would be helpful while building screens. “What city are they in? What is the last name of that character? What is the exact date?” It took a while to figure out there were often no solid answers and that productions sometimes wanted to keep those aspects as vague as possible on purpose. It just became easier to work around the details and get creative about hiding the holes. Nevertheless, I just remember expecting some of those details, especially timelines, would have been fleshed out.

Kirill: Do you worry about how your work will age / be seen in 20-30 years?

Jamie: Considering some of my work is nearly 15 years old, I should probably start to worry. But, no, I don’t worry about it. Style and design are a product of their time and some will age well, and some won’t.

While designing, I am definitely not thinking about future audiences. But I do have the contemporary audience in mind and am considering what they are familiar with, what visual shorthand can I use to reinforce the message. Mainly, I am trying to produce a style that matches the character and the set design. When my work is seen by future audiences, I just want it to continue to mesh with the overall production.

Screen graphics for “2012” under the creative direction of G Creative. Courtesy of Jamie McCallen and Columbia Pictures.

Kirill: Do you find yourself competing with screens in your daily life? How do you craft something compelling that keeps the viewer in the story?

Jamie: Absolutely, I think we all compete with screens to some extent. It’s fairly common to be in situations where a person you are with is trying to finish up a message or post. For the most part, I just keep doing my own thing. If the person knows I am there and chooses to continue with what they are doing, I’ll respect that choice.

It’s kind of the same way in movies. You need to know what your message is competing with and how important it is. It’s not always about demanding attention.

As for your second part of your question, keeping viewers in the story. That’s key. We have all watched a show where something was off. Display graphics can suffer from the same types of problems. Sometimes they can be overly distracting, have awkward mannerisms, look out of place.

So, the first part of designing any screen is to just try to make sure it doesn’t stand out for the wrong reasons. Screens have to play their role. If it is a background textural screen, it should not call too much attention to itself. If a screen is given the chance to drive the story – be a “hero” – it needs to command attention and, as you said, be compelling.

To build a compelling hero screen, I think it should offer something unique and it needs to read clearly. For me, the process starts with the message. What story does the screen need to tell? Usually a screen is only visible for a few seconds, so it is important to figure out the core of the message and eliminate anything else. I try to strip out anything that I can read past and still get the whole message. Some of what is stripped out can be reintroduced later as secondary elements, but the main message should be as simple as possible.

Screen graphics for “Star Trek: Beyond” under the creative direction of G Creative. Courtesy of Jamie McCallen and Paramount Pictures.

Continue reading »

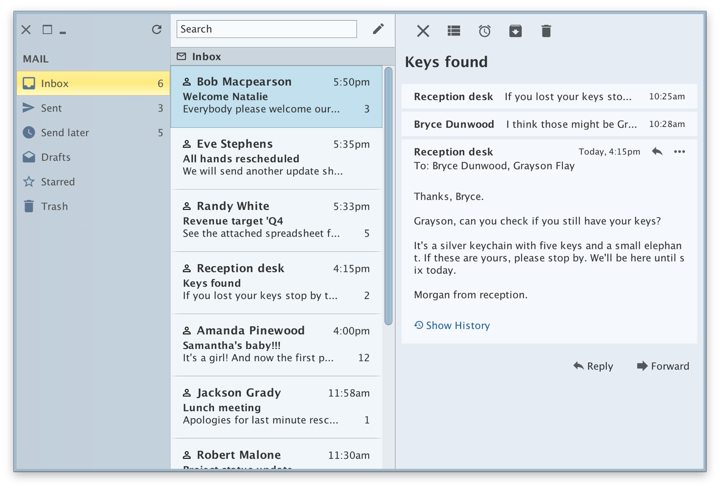

It’s been a few busy months since the announcement of Project Radiance, the new umbrella brand that unifies and streamlines the way Swing developers can integrate my libraries into their projects. Some of those projects have started all the way back in 2005, and some have joined later on along the road. Over the years, they’ve been hosted on three sites (java.net, kenai.com and github.com) in three version control systems (cvs, svn, git). Approaching the 15th year mark (with a hiatus along the way), it was clear that time has come to revisit the fundamental structure of these projects and bring them into a more modern world.

At a high-level:

- Radiance is a single project that provides a Gradle-based build that no longer relies on knowing exactly what to check out and where the dependent projects need to be located. It also uses proper third-party project dependencies to pull those at build time.

- Starting from the very first release, Radiance provides Maven artifacts for all core libraries – Trident (animation), Substance (look-and-feel), Flamingo (components), Photon (SVG icons) and others.

- The Kormorant sub-project is the first exploration into using Kotlin DSLs (domain-specific languages) for more declarative way of working with Swing UIs.

- Flamingo components only support Substance look-and-feel, no longer doing awkward and unnecessary tricks to try and support core and other third-party look-and-feels.

It gives me great pleasure to announce the very first release of Radiance, appropriately tagged 1.0.0 and code-named Antimony. Lines of code is about as meaningless a metric as it goes in our part of the world, but there are a lot of lines in Radiance. Ignoring the transcoded SVG files auto-generated by Photon, Radiance has around 208K lines of Java code, 7K lines of Kotlin code and 5K lines of build scripts.

It gives me great pleasure to announce the very first release of Radiance, appropriately tagged 1.0.0 and code-named Antimony. Lines of code is about as meaningless a metric as it goes in our part of the world, but there are a lot of lines in Radiance. Ignoring the transcoded SVG files auto-generated by Photon, Radiance has around 208K lines of Java code, 7K lines of Kotlin code and 5K lines of build scripts.

It’s been a long road to get to where Radiance is today. And there’s a long road ahead to continue exploring the never-ending depths of what it takes to write elegant and high-performing desktop applications in Swing. If you’re in the business of writing just such apps, I’d love for you to take this very first Radiance release for a spin. You’ll find the prebuilt dependencies in the /drop/1.0.0 folder, and if you fancy a more proper dependency management mechanism, there’s an answer for that as well . All of them require Java 8 to build and run.

Continuing the ongoing series of interviews on fantasy user interfaces, it’s my pleasure to welcome Bruno William. In this interview he talks about self-initiated work, VR interfaces, invisibility of good design and screen graphics in film and episodic television. In between and around, Bruno dives deeper into his work on the recently released first season of “Lost in Space”.

Screen graphics for “Lost in Space”, courtesy of Bruno William.

Kirill: Please tell us about yourself and what brought you to where you are today.

Bruno: I’m a designer based in São Paulo, Brazil. I always loved video games, music and movies, as well as martial arts. Art and design were always present in my life, directly or indirectly. Since I was a kid, UI or fictional technology was always being there in movies like “The Matrix”, “Terminator” or “Alien”, even if at that time I hadn’t realized it yet.

The Internet was my main source for study when I started out. You study and talk to other artists and designers, and absorb the knowledge. For me, that process still goes on today, and I’m still passionate about UI design, technology and storytelling.

The Internet was my main source for study when I started out. You study and talk to other artists and designers, and absorb the knowledge. For me, that process still goes on today, and I’m still passionate about UI design, technology and storytelling.

I was studying a lot of things like CGI, 3D character design, motion design – all by myself, even when it was frustrating. I knew that I wanted to work in the entertainment industry, doing art or design for film and video games. As I was trying to find myself or do something that I loved, I found the UI work that Ash Thorp was doing for film. That was a pivotal moment for me, to see all that knowledge and the way he approached it. It gave me a bit of confidence to pursue what I love.

Those were my early inspirations, artists like Ash, Nicolas Lopardo, Alan Torres and Jayse Hansen, whose work I was studying at that time.

Self-initiated work by Bruno William.

Kirill: I saw a number of self-initiated projects in your portfolio. How do you approach starting a project without any specific requirements about it?

Bruno: I always struggle with personal projects, and I think that’s expected when you’re starting out as an artist. When you work for a client, you have some kind of direction or a “problem” to be solved. When I do a personal project, my goal is to study and understand what I have to improve.

I usually try to create a quick story behind the project. That way I can have a topic or two that can help me with my creative process. It’s common to say that you need to do a personal project, but you’re not sure what you want to do or what you can do. The best thing for me with my personal projects is to create the problem in my head, and then work to solve it.

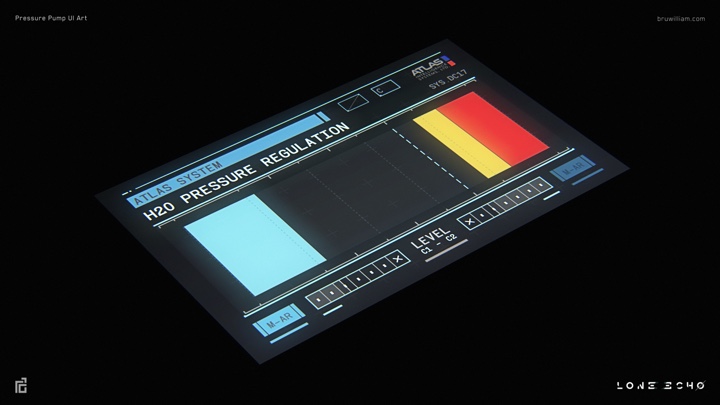

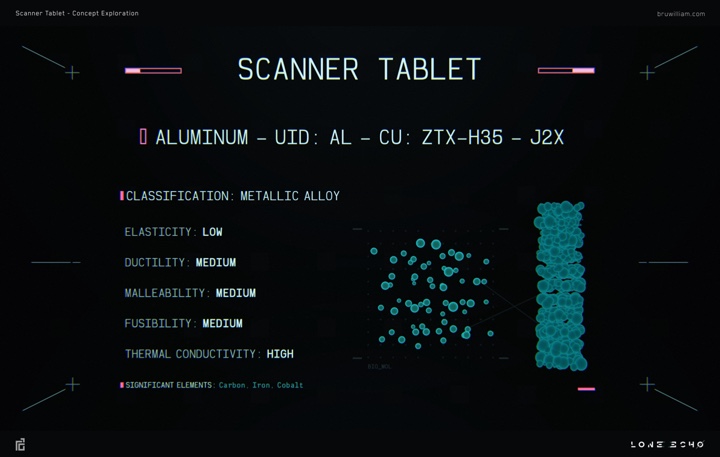

Screen graphics for “Lone Echo”, courtesy of Bruno William.

Kirill: What can you tell about the project you did on designing a game interface in VR?

Bruno: That was “Lone Echo” and it was a huge challenge. It was my first AAA-game, and it was my first time working in the field of VR in general. You usually create 2D, flat screens for devices that the user can touch or interact with physically. With VR, the question becomes how do you organize that information in a 3D space around the player.

The most challenging thing on this project for me was to figure out how to make the information clear and functional to the player in 3D space. How do the elements interact with each other, as well as with the player, in an intuitive way?

When it comes to design, it needs to be rooted in basic principles. We need to keep things simple as much as possible. Everything needs to be easy and readable. If we use tiny details or thin lines in VR, it can be annoying for the players. Reading and understanding a small text element in the 3D space can be a frustrating experience from the readability perspective.

On “Lone Echo” everything needed to be bold and readable. It had to be structured and organized, avoiding tiny details.

Screen graphics for “Lone Echo”, courtesy of Bruno William.

Continue reading »

Continuing the ongoing series of interviews with creative artists working on various aspects of movie and TV productions, it is my honor to welcome Inbal Weinberg. In this interview she talks about her dream of becoming a production designer, finding the right projects to work on, the invisible craft of production design, doing research in the age of the Internet, and what keeps her going. Around these topics and more, Inbal goes back to her work on “Blue Valentine”, “Beasts of No Nation” and “The Place Beyond the Pines”, dives into building the worlds of the critically acclaimed “Three Billboards Outside Ebbing, Missouri”, and reflects on the much-anticipated upcoming remake of “Suspiria”.

Inbal Weinberg on the set of Billboard Road.

Kirill: Please tell us about yourself and the path that took you to where you are today.

Inbal: Probably contrary to a lot of other people in our field, I’ve always wanted to be a production designer. While in high school in Israel I was studying drawing and painting, but realized I didn’t want to be a full-blown artist. That’s the time I really got into movies. It was the beginning of the indie film wave in the US, Hal Hartley was my favorite filmmaker and I loved Ken Loach and Mike Leigh in the UK. There were a lot of other active filmmakers I liked around mid-90s, when I was in high school. That indie film “revolution” affected me a lot.

I can’t say what it was, but the credit ‘production designer’ just caught my eye. Even though I knew absolutely nothing about it, I sort of invented what it was in my mind and decided that’s what I wanted to do. I remember very distinctly that when I was in the Army, I told people I was going to be a production designer – without really knowing what it was.

I tried to find out more about it. At the time it was just the beginning of the Internet, and there wasn’t that much information available to you offline either, especially if you lived in Israel. I remember going to the Tel Aviv university’s library and trying to find books about production design – which didn’t exist.

I decided I wanted to go to film school in the US. I wanted to leave Israel and live in New York. There weren’t undergrad production design programs anywhere at that time, and even today there are very few. So I decided to apply to NYU just knowing that it was one of the best film schools in the country.

Production design of “The Place Beyond the Pines” by Inbal Weinberg.

I went to talk to the Chair of Film School before I even got in and asked him what he thought about me wanting to be a production designer. He encouraged me to attend, saying that filmmaking basics are always important. And at the same time, because not a lot of craft people go to film school, I would probably have ample opportunities to design student films.

He was totally right about that. I went to film school at NYU and had the ability to work on a lot of student films. The school was also pretty receptive to me asking to tailor my own studies to my concentration. I think they didn’t have a lot of people that were asking to do that. I took the required film classes, but I also took classes in the theater department learning to draft scenery, in the Cinema Studies department learning about history of production design. I sort of put it all together.

The indie film world is the world that I wanted to be in, and I started doing a lot of small films. I went through many positions in the art department, slowly going up the ladder. At some point I felt it was time to try designing my own films. I started with really small ones, and kept going from there.

Kirill: Was there anything particularly surprising or unexpected for you when you joined your first production?

Inbal: Reflecting back on it, I probably self-importantly thought that I knew everything, but really I knew nothing. It was a humbling experience, where I learned how little I actually know. Come to think of it, to this very day on every project I realize how little I know. That hasn’t changed much [laughs].

I’m always surprised by how much I learn on every project. Production design is this huge field where you can become an expert on so many different things. Depending on the project, you learn about the history of very specific subjects, or you learn a craft that is really specific for your film. People-managing is also a big part of the job, and that’s something that most of the time you learn through experience.

Production design of “Blue Valentine” by Inbal Weinberg.

Continue reading »

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()