Who am I? I am Sugar. I am what you would call a fallen woman. But I assure you I did not fall. I was pushed…

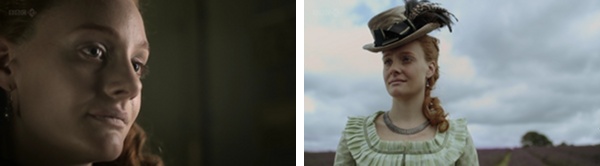

This is the tagline of “The Crimson Petal and the White”, a mini-series that unfolds the story of a young prostitute named Sugar living in London in 1875. Played by Romola Garai, the young girl chances upon a married heir to the family perfume business and uses her passion for literature to ensnare his mind away from the unstable situation at home. Pushing the limits of broadcasting censorship, “Crimson Petal” offers an unfettered look at the lives of rich and poor – alternating between unsettling and riveting, revolting and fascinating, voyeuristic and enchanting.

Sugar’s fiery golden tresses highlight the sensuous setting of the local brothel, with deep reds, greens and golden browns welcoming the customers onto the premises.

The first encounter between Sugar and William Rackham places the viewer at a nearby table, with dancing candlelight flames and blurred reflections framing her face. As she deftly weaves the conversation and plays to his vanity, the camera never goes below her neck, highlighting his noetic enchantment with Sugar.

This is the beginning of a scene where Rackham talks to the brothel’s mistress, offering a full patronage arrangement for Sugar. While the conversation is very detached, deep reds and yellows highlight the very intimate nature of the transaction. Note the richness of the dress, chandelier and the tapestry – all in the area that welcomes the customers.

As Sugar herself is listening to the conversation, the camera places the viewer half peeking from behind a curtain. The cool colors of the environment – turning her fiery hair into sand brown – highlight her emotional detachment from the impending transaction. She has been planning this move all along, deftly planting the idea seed in his mind. All that is left to do is to complete the deal.

And here she is, a few moments later, entering the scene and “adopting” the rich sensual palette that washes her hair and face in deep ember. This color transition from warm to cool and back to warm is one of the best color sequences in “Crimson Petal” and is certainly worth rewinding a couple of times.

With Rackham back at his house, Sugar bids farewell to the mistress. A short conversation reveals many intimate details, including how the mistress (which is also her mother) pushed her to sell her body. The dialog is brief and very cold, and is washed in desaturated browns, cool blues and soft yellows – with not a single hint of a warm color anywhere in the frame.

As the story begins to unfold in the winter, the outside scenes in the Victorian slums are dominated by grays tinged with sea green.

Even these few short moments that the main characters spend outside are enough to show the destitution and despair that engulfs the poor parts of the capital. The stark contrast to the lush interiors of the Rackham residency is just another reminder of why Sugar is so desperate to claw her way out of this misery.

As Sugar’s plan begins to materialize, the plot gives additional meaning to the name of the series (and the book it is based upon). Michel Faber that wrote the original book explains the many meanings of the name:

It comes from a Tennyson poem that begins “Now sleeps the crimson petal, now the white”. But the poem has no particular relevance to my story. I like the complexity of associations suggested by crimson and white—Sugar is a “scarlet woman” but she is mistaken for an angel by Agnes Rackham, and is also desperate to move into a new life that’s respectable and innocent. Agnes is, by birth and inclination, pure white, but is troubled by the phenomenon of blood. William uses and destroys petals of both colours in his profession of perfume manufacture.

This is just one of many scenes that happen in the Agnes’s bedroom. Bedridden with frail body and mind, she spends most of her time surrounded by the sea-green floral patterns of the wallpaper, oppressed by the frequent visitors of the family doctor.

Elsewhere in the house, the wallpapers and tapestry are much lighter and warmer, with bright patterns dominating the dining room and mahogany red wrapping the main family room.

This is one of my favorite shots. This is the outside of Rackham’s factory that packages various perfumery products for domestic and international shipping. As inconspicuous and slightly decrepit as it is on the outside, it only serves to enhance the visual impact of the interior design, with its immaculate color palette, ornamental embellishments and intricate woodwork:

Luke Dunkley did the editing for this wonderful mini-series, and you can imagine how delighted i was when he graciously agreed to answer a few questions I had about his work on “Crimson Petal”

Kirill: Tell us a little bit about yourself and your busy schedule.

Luke: I’m a freelancer of TV drama and have been for 15 years. Budgets have steadily been reducing in real terms so schedules become ever more squeezed. So I find myself in the cutting room from pretty early to late in the evening.

Kirill: As the editor, how important is it to spend your time on the set reviewing the daily shoots?

Luke: I spend very little time on set. In fact I feel like a spare part when I’m there as there’s nothing for me to do except be positive about the dailies I’ve been given. There is the odd occasion where it’s necessary to visit the set for a specific problem but they’re rare. However, reviewing the dailies is terribly important; I need to be able to watch them and give constructive feedback to the director on set. Feedback can range from coverage (the lack of it and whether it will cut together as a story and whether we need any pickups) to an actors performance up to the look of the show.

Kirill: Given how much time you spend with the director during the post production stage, is there a special bond of trust that is developed?

Luke: Definitely. It’s essential. The more you work with a director the easier it is to interpret their vision. You build a trust that works both ways; so if I say something isn’t working, even if the director loves it, then they will listen. They won’t always change it but they will listen. Plus, if you’re with one person for 12/16 weeks you have to have fun.

Kirill: You’re mostly doing TV productions for BBC these days. Knowing the hard limits on each episode length, how far is the editor’s cut from the final product that the viewers see on the screen?

Luke: By editor’s cut you mean the 1st assembly I think. That is always 10 to 20 percent longer than the final product. It’s usually in scripted order and it has what I call fat in it. As an editor you know from that assembly where you want to make trims, add music, move scenes and generally start shaping it. Depending on the director you could do that before they see it in scripted form or, if they trust you, you can start shaping it before the end of the shoot. Mostly I’m somewhere in the middle.

Kirill: On a related note, how different are editor’s days between the movie and TV productions?

Luke: None really. They’re all long.

Kirill: How much of the eerie atmosphere of “fallen” London streets and the opulence of the upper class surroundings was done during the post production? Is it mostly the right selection of camera equipment or dynamic software processing?

Luke: Obviously the design was a huge factor, which meant that Lol Crawley (director of photography / DOP) could shoot it in a particular fashion. What we did in post was a combination of sound, light and image manipulation. Very early I started playing with the idea of drones. I sent Marc Munden (director) a cd of about 90 drones that he loved (not all of them). We added them to scenes for atmosphere and tension. Lol (DOP) and Grant Montgomery (designer) did such a fantastic job that when it came to grading the series they had a great deal of scope. And finally image manipulation; there are about 50 shots per episode that we changed from their original format. This might have been as simple as adding a zoom, but occasionally I would stretch an image (a bit like a circus mirror) to hopefully add unease. You can’t stretch it too much though or it looks silly.

Kirill: What part do the advances in professional editing software play in merging all editing responsibilities in the hands of a single editor? What are your current tools of trade?

Luke: I’m currently using Avid media composer and have done for years. I like to think that the tool doesn’t make that much difference it just makes you quicker (I can cut as quickly as I think). Obviously nowadays you are expected to add temp music, vfx and sfx and this is made easier in the non-linear world.

Kirill: “Crimson Petal” has a lot of close-ups with dynamic focus and lighting effects. Is this something that you’re doing during editing, dynamically altering the frame selection and applying various continuous effects?

Luke: Not really. Lol used 1970s Prime Canon lenses that had a very shallow depth of field and a slight softness to them. I thought it looked great but you should ask him about that.

Kirill: Some of the productions you’ve worked on (including this one) are adaptations of much lengthier books that have the luxury of conveying characters inner thoughts. How far can you as the editor take an adapted script and use the visual tools at your disposal to bring the viewer closer to the original complexity?

Luke: It’s very hard, especially if there’s an inner voice. you can get round that with voiceover/narration, but that is very much down to the screenplay/script.

Kirill: Some people spend inordinate amount of time ferreting the smallest physical discontinuities, even if they don’t matter for engaging the viewers in the emotional story lines. Is this something that bothers you?

Luke: Not at all. If someone is overly concerned with continuity then we have failed them because they’re not engrossed in the story. There’s a very obvious continuity jump in Crimson where Mark Gatiss’ character knocks over a teapot and the proceeding shot it’s upright. We kept it in because on numerous viewings it was never noticed, people were watching the actors not the props. The best take for performance is always the priority.

Kirill: Can you recommend a few of the productions (movies or TV) that have particularly impressed you?

Luke: There a whole host coming out at the moment that are very good, I think British drama is in rude health. I’m particularly enjoying the Shadow Line at the moment.

Kirill: What’s next for Luke Dunkley? What are you working on these days?

Luke: Currently I’m working on the first three episodes of a new BBC3 series called The Fades. A graphic comedy horror – should be on screen in September.

And here i’d like to thank Luke for his work on this production, and once again for taking the time to do the interview. As for the readers – i hope you enjoy the series as much as i did.

In my last entry i talked why i see “Tron: Legacy” as the best 3D movie experience that i’ve seen so far, and it’s my great pleasure to have Bradley G Munkowitz aka GMUNK join me for a conversation about the work he and his team did on the movie, extending it to the visual effects in general and a glimpse into the not so distant future of movie-going experience.

Kirill: I was reading about the background of the movie itself, and i’ve read that it started in 2007 when there was this big writers’ strike and it started with Digital Domain pitching Tron:Legacy to Disney. Were you part of that phase, or were you brought later?

Gmunk: I was freelancing for Digital Domain, so i’m not a staff employee there. So they hired me as an independent contractor to build a team that was involved after the VFX tests and pre-viz. They hired us to be the concept and the execution.

Kirill: So pre-viz is like a proof of concept?

Gmunk: What you’re talking about, the VFX tests, that is the look development. It’s “we want to make Tron and we want it to look like this, all dark, in a stormy world when everything is glass”. Then they take that look and they pre-viz the whole movie where it’s all done in 3D, but it’s not rendered. It’s a crude structure so that you can see and edit it, almost like the next step from storyboarding. What the shots are, where the camera is, where it’s moving.

Kirill: But it’s beyond the still shots and color schemes, right?

Gmunk: It’s in junction with. And so my team was brought in to do the look development and execution of key holographic UI sequences.

Kirill: So that was somewhere in mid-2009?

Gmunk: It was the end of 2009, yes.

Kirill: And it took you about a year until the final completion, with the movie released in December 2010.

Gmunk: Yes, it was about a year. The team scaled from me all the way up to five people who were brought in at different times [see the links at the end].

Kirill: It was about 800 people working on the digital art of the movie. So five people doesn’t sound a lot.

Gmunk: That’s true. Digital Domain has its own visual FX pipeline with giant teams doing giant strides. And we were this outside unit that just parked in a corner of Digital Domain facility and just did our own thing. So we were kind of a special team.

Kirill: But you guys did the vast majority of the real work on the VFX part

Gmunk: The VFX part of the select scenes in the movie. We were not doing the VFX for light racers, for example. We were doing small niche graphical interfaces, data visualizations. We did the opening titles, the fireworks and a few other scenes. It’s all on my site.

Kirill: You mention on your site that you worked in close collaboration with the movie director. Can you describe the process?

Gmunk: I knew Joe [Joseph Kosinski] personally since we worked together on the Hummer commercial two years prior, so he felt comfortable just coming over and sitting down with us. You get him for 45 minutes to concept out what it is that we’re doing, what the task is, sketching it on a sketchpad. And then we’ll take it for two or three weeks and show him our solution, he’ll critique it and we’ll start refining it. We had five really key reviews which would trickle into the VFX shots and then to the desk of the VFX supervisor who wants to have proper depth of field, for example. This is integration stuff that gets critiqued more and is in front of everybody’s eyes on the daily basis. For the core conceptual look development stuff we had three or four review cycles with Joe and then it would go into the VFX pipeline.

Kirill: So you were doing all of the scenes in parallel?

Gmunk: There was a ton of overlap for sure. We were just a team of five, and it takes a lot of time to get that super grunt work done. There were big tasks, like for example the solar sailor sequence which took us three months, while we did the opening sequence in about a month and a half. Fireworks were quick – there are a lot of these quick design bits where we would do interfaces for the bikes or the throneship – those were couple of weeks.

Kirill: You also mentioned in one of your summaries that originally you were contracted for about five minutes that later expanded to ten. Was it more scenes, or more content in each scene?

Gmunk: It’s definitely a good thing to get more opportunities to jam. It was definitely different scenes. We were killing ourselves doing the solar sailor, and they would come in asking to do the opening titles and we were “OK, let’s add that to our list”. Or we would be heavy into the throneship rectifier extraction where they were decoding the disk, and they’d ask us to do the fireworks. So it would be a completely different thing, and we’d have to develop and concept it. We looked at it as a good thing, because we were super-inspired and we just wanted to jam.

Kirill: Well, the end result is amazing. Did you have something that you worked on and then the entire scene was cut?

Gmunk: Not on this one. I’ve had that happen before. They would advise us on a lot of stuff. A lot of eyes looked at our graphics and had comments after the core development, and a lot of stuff was dumbed down a lot, but never killed.

Kirill: What do you mean by dumbed down? Removing extra fluff?

Gmunk: “Removing extra fluff” is a good description. It’s like taking out the greeble. It looks awesome – the more complex, deep and insane it looks, the better, but sometimes it sacrifices the quick read on what it is supposed to represent with its conceptual cues. And so, we definitely had to take out a lot of greeble so the point of the graphics was understood quickly.

Kirill: In all the portfolio entries and blog posting by you and your team mates you spend a lot of time describing the underlying geometric primitives and algorithms behind the implementation, but not a single mention of the 3D aspect. Who did the 3D part?

Gmunk: We did all of 3D. We would put a lot of compositing into the Digital Domain pipeline because we weren’t the end people for these shots. We did the elements and then work with the compositor that would comp our elements into the shot under mostly mine and Jake [Sargeant]‘s art direction. That was one of the things that we didn’t do a lot – comping.

Kirill: So that would involve mixing it with live acting?

Gmunk: Exactly. Mixing it into the shot with actors within, casting lights on the actors. That was the big thing, because the holographic elements that cast the light.

Kirill: Do you have special screen hardware to check how 3D looked?

Gmunk: Not on our screens. There was a testing stereoscopic 3D television called “The Hyundai”. We would go in there and check.

Kirill: So you would go there and check if it looks good?

Gmunk: We developed so much stuff. Digital Domain has a very special VFX pipeline, there’s nothing else like it. And we found a way to get these stereoscopic 3D cameras into our 3D applications, like Cinema4D. We used a lot of openFrameworks applications that had to take in these stereoscopic cameras. Digital Domain had a technical director Jon Gerber who helped us accomplish that, to write the scripts to get the cameras to go into Cinema4D and openFrameworks. And then out of our 3D apps we would render stereorenders and then check those on The Hyundai.

Kirill: There’s a lot of complaints that movies shot in 3D don’t look very good in a fixed-eye projection system – if you buy a BluRay disc for your home TV or go to a regular screening. Did it take care of itself because the 3D aspect in Tron:Legacy is so muted?

Gmunk: I think the use of 3D in Tron is the best out there. It was so tame and tasteful. We never had an interface to make that was supposed to knock you upside your head. Our stuff was always medium and wide shots of whatever holograms they’re using.

Kirill: That was also my impression. Even in the solar sailor scene where the guys extract the virus from Quorra’s DNA and there’s a lot of camera panning, it was all very subtle. Was it an explicit directive from the movie director, not to go overboard with 3D?

Gmunk: That’s very much Joseph’s style. Kosinski’s style is always very tasteful, beautiful and elegant. I think the best example was during the light jet fight. It was always done in a really tasteful way, even an exaggerated shot of a ship coming directly to camera and then diving back down when it runs out of gas. It doesn’t come super close, but just close enough so you see. That kind of stuff is awesome, it’s perfectly controlled – and that was all over the movie. In the light jet scene there were a couple of times where the jet flies by camera but it wasn’t right by camera, it was kind of off to the side. We got to see in dailies every day the work of the VFX supervisor, Eric Barba – he’s the man. Watching him critique a 3D image in stereo, pinpointing all the problems, citing interocular distances and the convergence points, picking apart the 3D image – it was amazing. That was my favorite part – watching Kosinski and Barba work together and critique images. It was being in a super advanced design school.

Kirill: Sounds fascinating. Do you think that the industry is still making baby steps, exploring the right ways to shoot, edit and composite 3D movies?

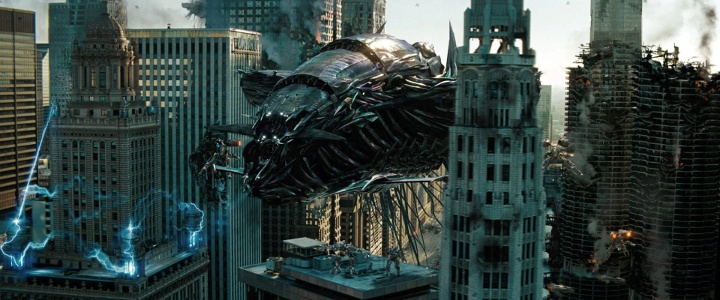

Gmunk: There’s a lot of movies that do 3D after the fact, and that’s awful. I think that “Transformers 3” is going to be a really good test of where it is right now. That is a 3D explosion movie, that’s an upper cut, that’s a smack you across the face grand effects movie, and if they can nail that stereo so that it is super frenetic, but in a tasteful way that doesn’t crush your brain, that’s a big step forward. My favorite 3D implementation is still “Avatar”. I thought the camera work in that movie was so beautiful, so well done. Every single shot, the camera feels completely hand-held.

Kirill: All of the movies that you mentioned – Transformers, Avatar, Iron Man and of course Tron: Legacy – are confined to the “escapist” genres of sci-fi, horror, animation and adventure. Do you think over the next few years, or perhaps a couple of decades it will transition to “Oscar-type” productions?

Gmunk: I think film makers are such purists, that for the sake of respecting the medium it will take them longer. Oscar-nominated movies will take perhaps ten to fifteen years before it happens. It should be in five, but people are going to stay true to the art form a little longer. Until going to the movies is completely immersive. In fifteen years a movie theatre is going to be an interactive 3D fully-realized hologram in front of you. You’ll be on those flying mountains, you’ll be able to touch the wing of the Ikran.

Kirill: Will this translate to the TV experience in my living room?

Gmunk: I think the theaters will be fully immersive crazy kick-ass ones, and the living room will be a scaled down version, with perhaps hard-core super gamer types who drop eighty grand on their system to get the full experience.

Kirill: I think it was “The Lawnmower Man” which had this immersive gaming experience. That never happened, right? And that was 20 years ago.

Gmunk: May be i’m getting ahead of myself. But things are getting pretty cool. I think in five years your phone will be able to project something out of it that makes something you can use.

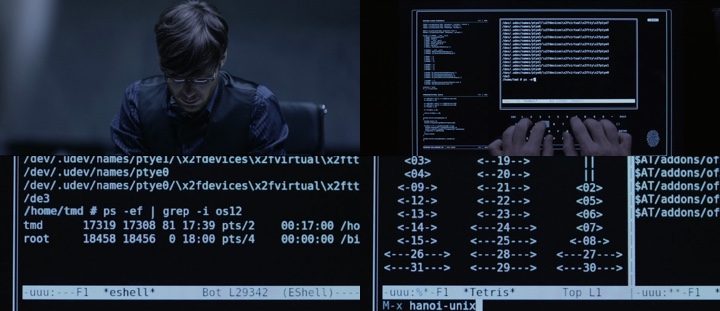

Kirill: This brings me to the topic of futuristic UIs. I’ve been reading Josh Nimoy’s blog that talked about bringing realism into the hackery scenes, showing emacs and proper Unix commands. Do you ever get told to forget about how realistic it will look to the geeks and instead to concentrate on wowing the audience?

Gmunk: What Josh did was awesome. I was talking about purists, and he’s a purist. He’s an artist and you always have to plant these Easter eggs in everything you do. You have to stay true to your roots and plant those little reminders. This is what Josh did, he went old school and did a retro thing that nobody but geeks would appreciate – and that’s what’s important for him.

Kirill: Now that the movie is out on BluRay, do you get emails from those hardcore guys that dissect every single still from the movie?

Gmunk: He probably does, and that’s cool – you’re touching people. The average movie goer is perhaps looking at the surface level, with nothing to really grab them and touch their inner passion. But geeks and people who live for this – they are just more educated fans that appreciate this aspect, and that’s who we care about.

Kirill: Do you need to get an approval from the director – to plant those Easter eggs?

Gmunk: I don’t think the director knew [laughs], but i think that he would appreciate it as much as Josh did. We’re all purists, we’re all indie at heart. When i graduated from college, i preached that i would never do client work in my life. I was completely anti corporate America, a vegan (still am), super against the carnivores, super environmental. So i made a pledge to do what’s right and that quickly faded when i moved to Los Angeles.

Kirill: Somehow you need to pay your bills…

Gmunk: Right. So you always want to throw in the whatever indie respect that you can give. I try to do that a lot with commercials too.

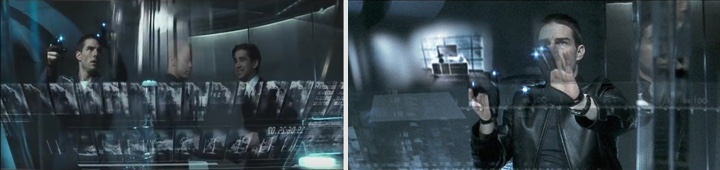

Kirill: Talking about the futuristic UIs. Whenever it gets mentioned, people always seem to be talking about “Minority Report”. It seems that only that movie managed to capture people’s imagination on what the interaction with computers will look like in the future. Do you think that the way we interact with computers every day at work and at home will change?

Gmunk: First of all, the reason why it was the most accurate representation of the UI is simple – it was developed at MIT. They had computer scientists and UI specialists that research this for a living design this interface. Mostly in movies it’s just greeble – just make it look awesome and don’t think about making this a real-life thing. Kind of like “Iron Man 2” – the implementation was gorgeous, and that may be a real-life hologram some day – but did they really thing about usability and would that mirror what would happen soon? The thing about “Iron Man 2” and more so about “Minority Report” is that it’s all gestural. It’s all about controlling things with your hands, interacting with your hands, taking everything off the mouse and the keyboard – which we’re already seeing starting with iPads and iPods and the gaming consoles. That’s the way it’s going, and basically every UI you’ve seen in the last ten years in a movie has been touch-based, with gestural controls. I can’t remember the last UI i saw in a movie that had a mouse.

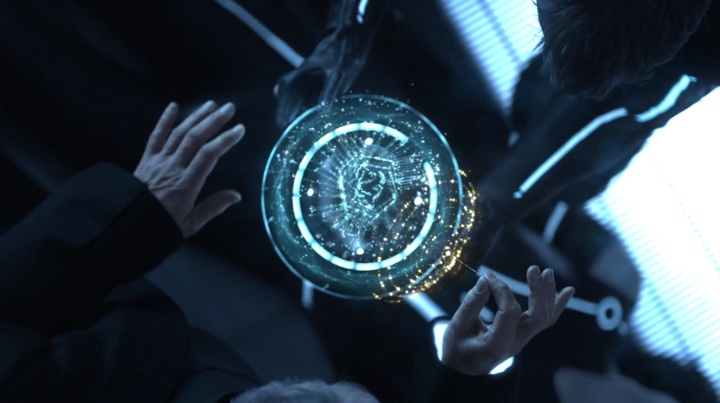

Kirill: We mentioned “Iron Man 2” a few times. I was reading this article which says that Robert Downey Jr. would improvise his movements on the set, and then the VFX artists would need to build the entire holographic UI around his movements. How was your interaction with Jeff Bridges in the elevator and solar sailor scenes?

Gmunk: We were just given the footage. We weren’t involved in the shoot of those sequences at all. Unfortunately, in the elevator shot his hand is completely out of focus. They shot everything at f/1.4 and everything has a crazy shallow depth of field – and so the graphic had to be out of focus, which was kind of a bummer. The solar sailor had also a shallow depth of field, so that was something that we had to work with to get our renders right.

Kirill: So you got the shots of him staring into empty space and moving his fingers around, and then you built your scenery around that? Is this more interesting than creating your interaction model and asking the actor to somehow work with it?

Gmunk: It’s way better to do it when actors are gesturing in the air and then design around that. It’s easier and also fun and super-inspiring, as long as the performance is good. He didn’t have a lot of definitive motions, with soft gestural commands and not a lot of emphasis, so we made the interface itself react to that and be less complicated. We made it match his gestures.

Kirill: I was thinking about the sci-fi movies that i’ve seen in the last decade or so, and it seems the best of them take place in darker environments – such as Matrix and Tron, of course. Your portfolio would also indicate that you’re moving in this direction. Is it because you can explore the futuristic environments better in an inverted contrast?

Gmunk: I just love dark, the vibe and the evil dark aesthetic. I love the original “Matrix”, it is by far the best sci-fi movie ever made. It had this nasty, really dark vibe to it that was so beautiful. And the plot lines and the language were so deep, intelligent, sophisticated, well thought out and written.

Kirill: Were you disappointed by the sequels, from visual as well as content point of view?

Gmunk: The third one was almost unwatchable. The visuals in the third one were cool, but it was really bad script. Everything every actor said was just a sentence, plus they got away from the charm of the first one where you see all the karate. And by the third one you have seen all the tricks and you didn’t care anymore, it was almost a video game. But the first one was amazing, and it still holds up today.

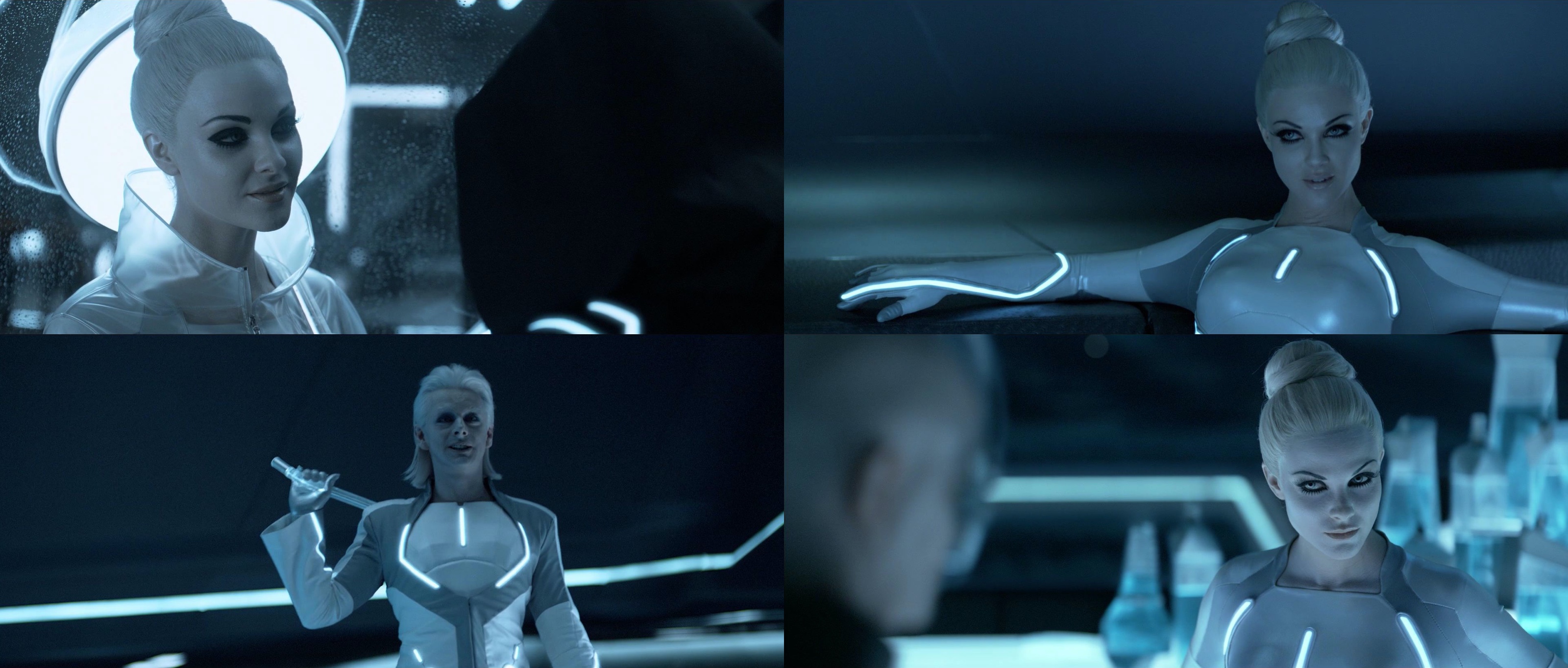

Kirill: Getting back to Tron and its dark environment. Did you feel restricted by the color space that was at your disposal, with soft blue for the good guys and yellow-oranges for the bad guys?

Gmunk: We got to love the glowing light blue a lot. But that’s just how it was. It would’ve been cool to see some pinks explored – no way it would go through of course. Some really nice cool pink.

Kirill: Did it somehow affect the exploration of different geometrical building blocks?

Gmunk: Not really, because we knew it would never go through. I would throw some yellows, and i think a pink slipped through once in a while – and we were told to change it. But some of the graphics got expanded colors. The board room, for example, got a full spectrum. We also designed the holographic animated rectifier globe in the scene where Clu addresses his army, and there were a lot of reds, oranges and browns there.

Kirill: How did it feel to see your work in the theaters, and all the geeks – including me – swooning over the effects?

Gmunk: It felt really good to see it on the screen with the audio, because we didn’t get hear any of the sound design. So hearing it was really quite a treat, because we didn’t have any creative input whatsoever into that. It was really interesting to hear the bits they added to the stuff that we were doing. You’re animating it and you think about how it will sound and you have ideas, and then they come back with something completely different. It was really fun. So the sounds the scoreboard made, the sounds of the hologram on the solar sailor when you click on it, the sounds of the DNA when it forms, the rings breaking apart in the rectifier extraction. And then hearing the sound track too was a part of it – a lot of the shots that we’ve seen, you’ve already seen on the big screen during the development on the theater screen in Digital Domain. But to hear it, that was a treat, the thing that i remember the most.

Kirill: So what can top your work on Tron: Legacy?

Gmunk: I think that if we’re doing another Tron, i don’t know what kind of charm it would have. But just knowing what we know now, learning from the process of generating these graphics, we can really push the envelope a lot further because we would hit the ground running. We would be full speed in the first week because we’ve been there and we know exactly what’s coming and we could pull off a lot more kick-ass.

One could only hope that James Cameron is already on the phone, tapping the man to lead the VFX team for the Avatar sequels. I’d like to thank Gmunk for this fascinating peek inside the VFX industry and for the incredible work he and his “black-ops team” did on the movie. Here are the links to their portfolios:

икони

In the last few years we are witnessing two intertwining evolutions of the movie-going experience. On one hand, the accelerated presence of large screen LCD and plasma TV sets is combined with BluRay as the winner of the high-definition optical disc format war to bring unprecedented viewing experience to the homes of hundreds of millions of viewers. On the other hand, the movie studios and leading producers are seeking to bring audiences back to the movie theaters, exploring novel ways to engage the movie goers and to stay ahead of the advances of home theater systems.

With relatively slow rollout of projecting equipment and small number of available films midway through the last decade, the year 2009 saw an explosion of 3D movie releases, culminating with the “Avatar” juggernaut that was released a week before Christmas and went to gross an unprecedented 2.78 billion dollars.

The 3D onslaught is only accelerating, spanning the lucrative genres of sci-fi and horror movies, teen concert documentaries and animation features (with DreamWorks switching all productions to 3D in early 2010). With the audiences streaming into the theaters and willing to pay a premium to enjoy a new experience, some studios have elected to take production shortcuts, seeking to quickly cash in on the new trend. Using traditional shooting equipment, these movies rely on the post-production phase to bring the third dimension not only to the computer generated visual effects, but to the live action itself. The abysmal “Clash of the Titans” and disoriented “Thor” are just two examples of post-converted productions; extrapolating the experience to the upcoming “Green Lantern” and “Captain America” does not bode well for the summertime superheroes movies.

Instead of beating a lame horse, let’s talk about the high-end productions that spared no resources, setting new standards for years to come and advancing the state of the art.

“Tangled” has captured my mind from the very first time i saw it in the theater, with me delving into the creative process behind the movie and interviewing one of the conceptual artists. After seeing it a couple of times in the “traditional” 2D format, i took a leap of faith and went to see the 3D version. Apart from a very few scenes that place the viewer in a dark tower, the movie is a veritable feast of vibrant colors, textures, strokes and patterns, with a small glimpse conveyed by this frame:

Here, we are placed in between Rapunzel and Flynn, with Rapunzel opening the curtains to reveal a gorgeous mural painting of floating lights, resting her hand on a ledge. The placement of the camera creates a very deliberate depth of field, with Rapunzel taking the front, and the mural serving as an inanimate companion to her words. As she is proposing the deal to have Flynn take her to see the lanterns, the mural becomes an integral part of the story that commands the viewer’s attention. This effectively creates two “planes of interest” – equally important and visually demanding.

As a viewer placed in such a scene, i found myself subconsciously switching my attention between these two planes, trying to take in the entire scene, following her words and attempting to study the finer details of the girl gazing into the night sky. This is something that we do every single moment that we’re awake. The brain directs the eyes to continuously scan our surroundings, partitioning the environment into different spheres of interest, gathering finer details in what it deems to be important and detecting peripheral changes. Think about driving on a highway – with the car immediately in front of you being the most important sphere, followed by the car before it, a few cars to your sides and perhaps the car right after you. The spheres of interest expand outwards to the traffic further down the road, the upcoming merging lanes or exits, or perhaps even the darkening clouds that indicate possible rain. All of this happens on a subconscious level, with the brain collecting, collating and condensing the immense amount of visual information.

As the eyes are directed to the different spheres, they change focus to converge on different planes – a process succinctly outlined by film editor Walter Murch in his letter to Roger Ebert. Murch swiftly moves in to point out the weakest link in the 3D movie experience:

[…] 3D films require us to focus at one distance and converge at another. And 600 million years of evolution has never presented this problem before. All living things with eyes have always focused and converged at the same point.

This was the biggest source of frustration for me in the specific scene, and throughout the entire movie. With equally rich and lush visuals in both planes of interest in the specific scene in “Tangled”, my brain was interested in exploring both, directing the eyes to refocus based on the perceived distance as conveyed by the camera placement and the ledge depth. As the mural was slightly out of focus to maintain a realistic depiction of the scene, i found myself constantly distracted by trying to converge beyond the physical movie screen, expecting the mural to come into focus – obviously to no avail.

Murch further elaborates that the fixed convergence plane causes the viewer to spend extra cycles adjusting himself to the changing focus plane. I think that there’s a much bigger issue with most of the 3D movies today – they have too many planes of interest in almost every single shot, without accommodating the brain-eye cycle that expects to be able to switch focus at will between the different planes and extract the relevant details from each one of them.

This is another one of my “Tangled” favorites. Rapunzel’s braided hair with intricate floral arrangement is the closest plane. Flynn holding the two lanterns, along with the satchel in her hands fill the second plane. The floating lanterns reflected in the serene bay water form the incredibly detailed third plane. This staggered arrangement that has progressive blurring of the visuals to maintain realistic visuals was also seen throughout the lush outside scenes of “Avatar”:

In both movies, the astounding realism of the surrounding scenery causes a rather opposite effect – when the camera dictates the main focus plane, your eyes do not obey the brain that directs them to switch focus to absorb all the details. Which brings me to the best 3D experience that i had so far – “Tron: Legacy“.

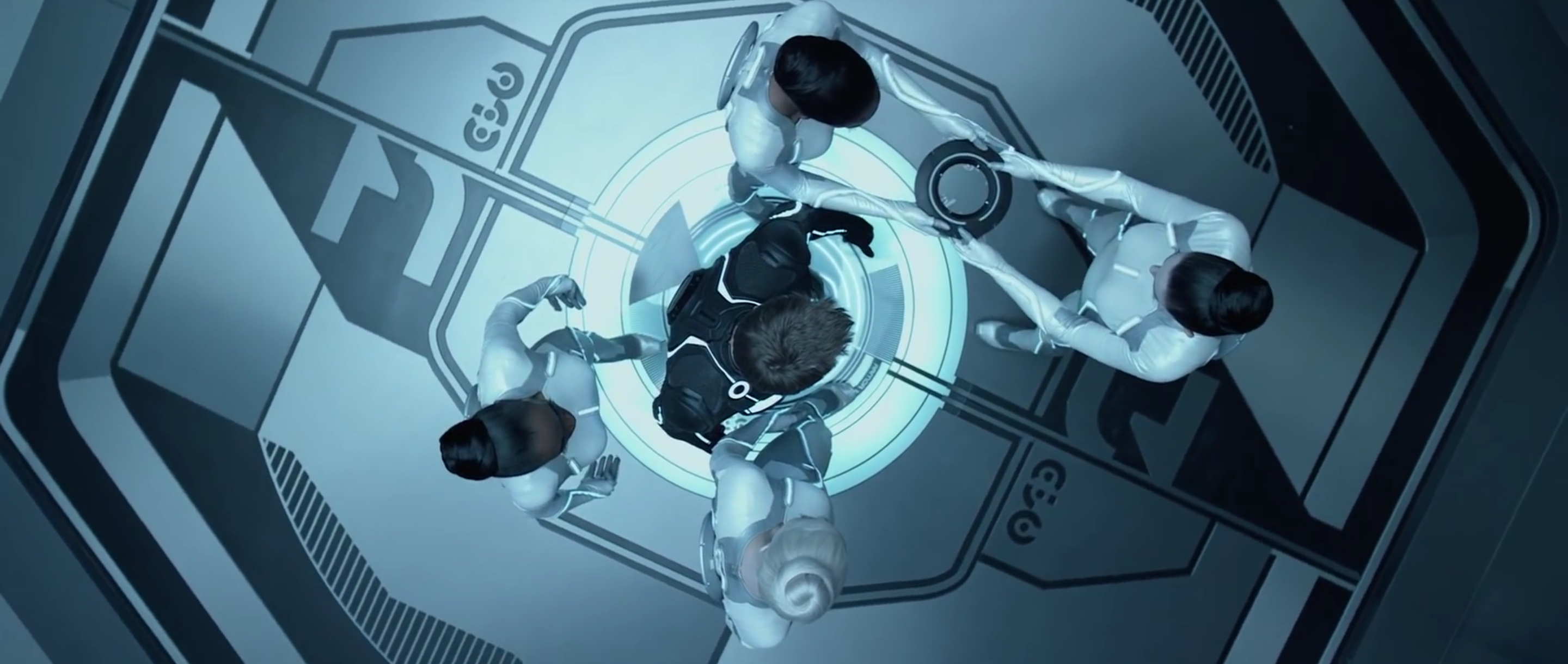

This overhead shot of the sirens getting Sam ready for the games is, as far as i could see from my three visits to the theater, the only time that the realism was sacrificed at the “altar” of 3D effects. Lasting a few short seconds, this angle creates a very unrealistic depiction of the scene. With the camera positioned directly above Sam, we have four planes – the heads, the shoulder pads, the disc exchanging hands and the floor – with every single plane in full sharp focus. With this rather unfortunate decision out of the way early on in the computer world, the extra dimension steps back and becomes just another artistic tool at the director’s disposal, simply blending away.

With an austere steel blue hue driving the predominantly monochrome color palette of the computer world, the production and set design cleverly masks away as much background as possible. Simple geometrical shapes, wide swaths of soft gradients and almost indistinguishable wall patterns make sure that the surrounding environment is not a plane of interest, but rather just a plane:

Note how little the brain is “stimulated” to spend time on the supporting visuals of the Safehouse – from the slanted slabs of obsidian to softly glowing curtain grid. The “End of Line” club is another masterful example of an environment that dissolves around the main characters:

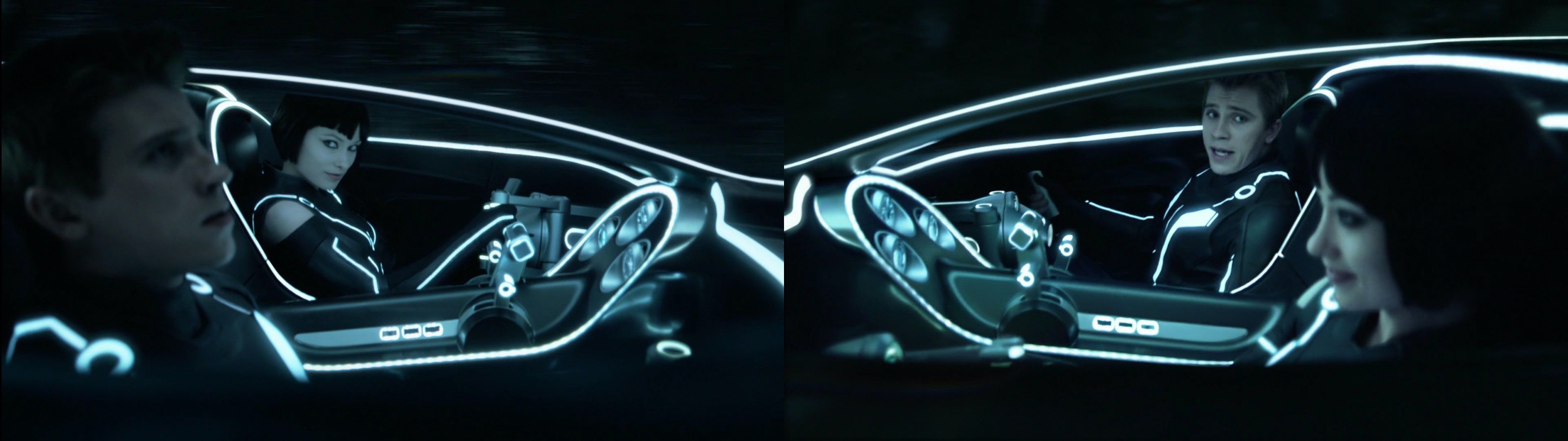

“Tron: Legacy” does an extraordinary job at keeping 3D on a short leash, keeping it as unobtrusive as possible and limiting almost every single scene to only one plane of interest. It’s rather interesting to see how it falls back to the “old” trick of significant focus switches in the light runner ride:

with the forced focus transitions between Sam and Quorra transitioning the viewer’s eye and providing just enough time to absorb the details surrounding the two characters before the next focus switch.

The next few years will undoubtedly see more experimentation and exploration in the 3D space. Some attempts will flop, and some will lead to breakthrough advances in the movie-going experience – that will find their way to our living rooms in due course. The sheer size of the consumer market will make sure that the movie studios and TV manufacturers will keep on relentlessly pushing the envelope, advancing the projecting hardware, screen technology and visual modeling in both academia and industry to new levels. More importantly, the movie creators will need to adapt the way the movies are filmed, composited and edited to maintain an immersive viewing experience. These are truly exciting times.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()