Continuing the ongoing series of interviews on fantasy user interfaces, it’s my pleasure to welcome Noah Schloss. In this interview he talks about defining success, communication skills, the difference between design and art, supporting the storyline, and the impact of generative AIs on human creativity. In between these and more, Noah talks about his work on screen graphics for “Star Trek: Picard” and “Westworld”.

Kirill: Please tell us about yourself and the path that took you to where you are today.

Kirill: Please tell us about yourself and the path that took you to where you are today.

Noah: My name is Noah Schloss, I’m a senior motion designer specializing in FUI currently working at Twisted Media. I have about fifteen years of experience, the last seven of which have been focused in the TV and film space. I’ve had the opportunity to work on some incredible projects like “Westworld”, “Star Trek: Picard”, “Fast and Furious Hobbs and Shaw”, “Morbius”, “The Godzilla/Kong” films, “Fallout”, “Borderlands” and others.

I started my career in advertising and made the switch over to TV/film when my good friend (now coworker) Clark Stanton, asked if I would freelance for Twisted. I started freelancing, and then joined the team full time, and have been at Twisted Media for quite a while now.

Kirill: Was there any particular thing that was surprising or unexpected when you started working in this field?

Noah: I didn’t expect to work on TV and movies from here in my home office [laughs]. The film industry can have some unexpected twists and turns, it can take some time to learn how to navigate. There are also technical aspects unique to film/TV that don’t have parallels in other industries.

Notes and feedback may also fall into this category. For the most part, folks in the film/TV space do a great job of focusing on what’s successful and supportive of the story we’re trying to communicate. Other industries might fixate on what’s wrong. It may seem like a subtle difference in communication but the net result is more concise directives. In an industry where directives are ever changing, the compounding effect can be substantial. Overall, I find this to be a more constructive environment for creative problem solving within large groups.

How to define success has also been a surprising take away from working in the Film/TV space. Over the last couple of years, I’ve been outlining what’s important in my process and learning how I internally define success more objectively. Success always starts with the resources available – not the least of which is time. If I only have 15-30 minutes to complete something, I take that into consideration when judging my own performance. Sometimes when talking with students coming out of school, they talk about a need to get a portfolio-ready piece every time that they put pixels on the screen. I had a similar attitude when I started, and it has changed quite a bit over the years.

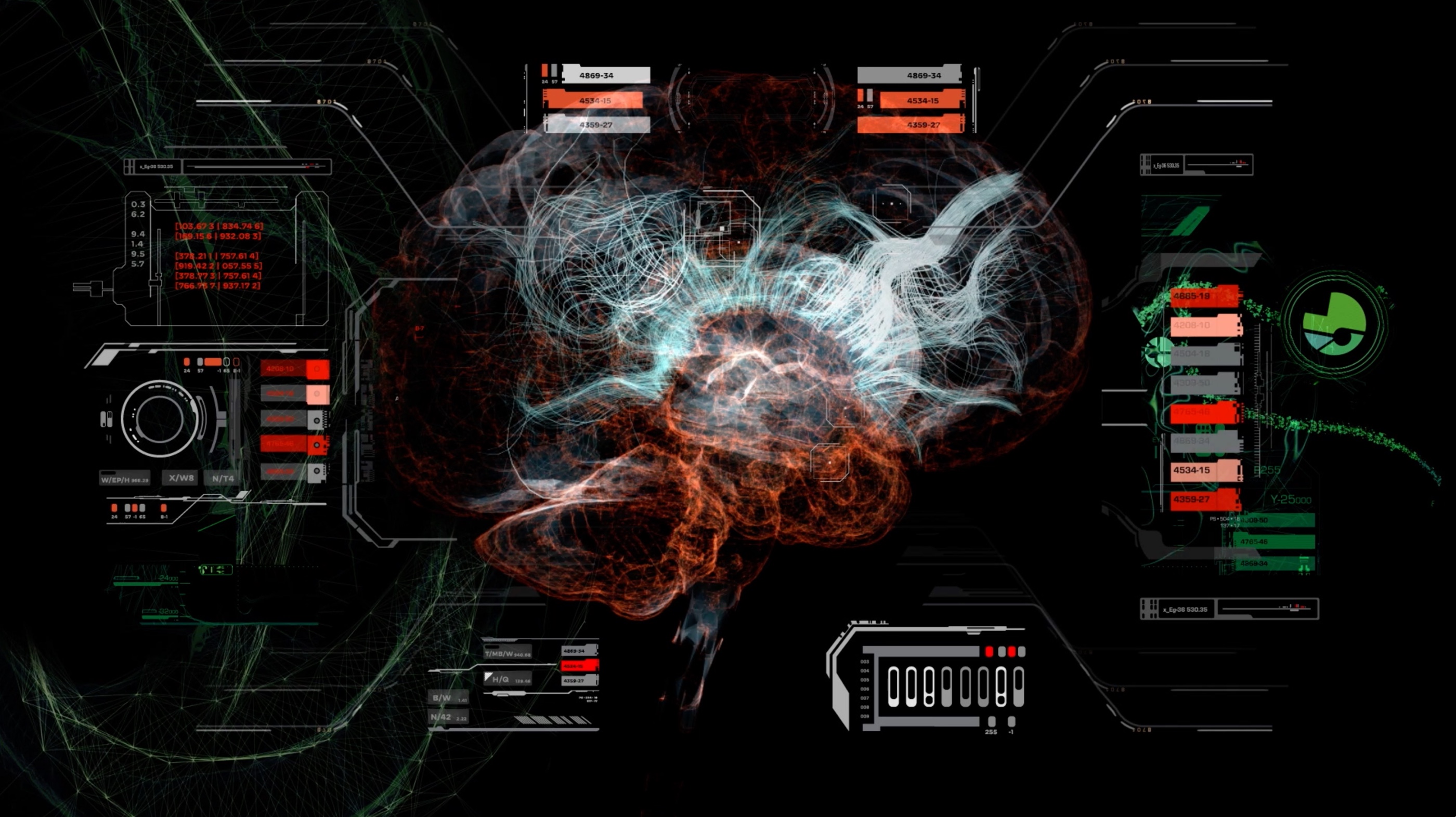

Screen graphics for Season 2 of “Star Trek: Picard” by Noah Schloss.

Kirill: You work for a studio, and the studio works for this big production, and there’s hundreds of people, sometimes maybe thousands of people. Does it feel sometimes that you can’t put a finger on something and say “This is mine”, because so many people participate in that?

Noah: Ownership, and the thoughts and feelings around that can be tricky for a lot of people. I always think of it like playing a team sport, my involvement is one part of the overall team’s success.

I’ve definitely run into people who don’t think like that. It’s difficult, because everybody is there to make a good product at the end of the day. The thing that ties it all together for me is understanding that this is a team environment, everybody’s here to pitch in and make their voice intermingle with everybody else’s, and hopefully make a cohesive whole versus a standalone piece of their own.

Kirill: Do you feel that for somebody who is just starting, for somebody who has strong ideas, it might be a little bit more difficult to participate in this team environment if they are not willing to compromise or accept feedback?

Noah: It totally depends on the person. I’ve found a lot of people in film/TV are looking for what’s right versus what’s wrong. That way of communicating with constructive criticism is the best way forward in any creative endeavor. It’s almost as important to focus on how you’re saying the thing that you’re trying to convey in relation to what you’re saying. Those communication skills help get the job done. You want everybody involved to feel like one cohesive unit versus a fragmented, segmented silo.

Screen graphics for Season 2 of “Star Trek: Picard” by Noah Schloss.

Kirill: How many times have you heard feedback along the lines of “I’ll know it when I’ll see it”, where the feedback is not concrete, where it’s not clear what it is that needs to be changed?

Noah: I’ve heard it a fair bit over the years. That’s part of the role that we’re filling in the filmmaking process though. We are sometimes charged with figuring out what the directive is, and in turn, try to come up with a “right” answer to that directive. I have this conversation a fair bit with one of my co-workers Chris Kieffer. You can have so many “correct” answers to the creative problem solving associated with FUI and filmmaking. Part of that process can be reverse engineering the design brief, and maybe saying that this works for this situation, and we’re going to move forward with that.

Given the timelines that a lot of film and TV productions have, you don’t have time to infinitely explore every idea. We are charged with dissecting the brief, coming up with a game plan, and quickly executing that, and then getting feedback and having this cycle to get where we need to go.

Kirill: What’s the difference between design and art for you?

Noah: I go back to what one of my professors at design school said in his human centered design program. His take on it was artists were always responding to the world around them, and then designers create the world around them. It was always an interesting distinction in my mind to categorize design and art differently like that. I still haven’t found a firm footing in one camp or the other, because one influences the other and vice versa.

You can take a framework like gestalt principles that’s supposed to be the “right way” to organize thought or lead people’s eye in the right direction. Those are helpful rubrics, but there’s also the postmodern school of thought, which is about throwing that out the window and see what else happens. I have Wolfgang Weingart’s book on typography, and he’s one of my favorite typographers that talks about throwing the traditional principles out the window. Even the cover of it removes most of the typographic form, and you still can read it. He was a master at toeing that line of form and function.

Screen graphics for Season 2 of “Star Trek: Picard” by Noah Schloss.

Continue reading »

Continuing the ongoing series of interviews with creative artists working on various aspects of movie and TV productions, it is my delight to welcome Tom Hammock. In this interview, he talks about balancing the art and the craft of visual storytelling, the blurring lines between feature and episodic storytelling, choosing his productions, and what keeps him going. Between all these and more, Tom dives deep into what went into making last year’s breakaway horror hit “X” and its surprise prequel “Pearl” in the middle of the global pandemic shutdown, and the enduring allure of the horror genre.

Kirill: Please tell us about yourself and the path that took you to where you are today.

Tom: I have a little bit of an odd path. My father is a scientist, and I grew up helping him out with that. I went to UC Berkeley in landscape architecture, and started working in the world of architecture. From time to time, my father would be approached by movies for scientific advice, and often he would have me give them the advice. I was doing that for the Sam Raimi’s version of “Spider-Man” while working in architecture, and they talked me into doing art dept work instead. I went to AFI for production design, and worked my way up PA’ing on big movies and designing small ones. And then we got where we are today.

Kirill: Do you feel that there should be one path for people to get into the industry, or that the industry benefits from this variety or diversity of backgrounds?

Tom: It benefits tremendously from the wide diversity of backgrounds. I’ve worked with art directors who came from everything as broad as picture cars to draperies work. Those are so widely separated from one another, and yet so integral to the design and the final product of a movie. All those backgrounds are wonderful. It’s great people that come from so many different places.

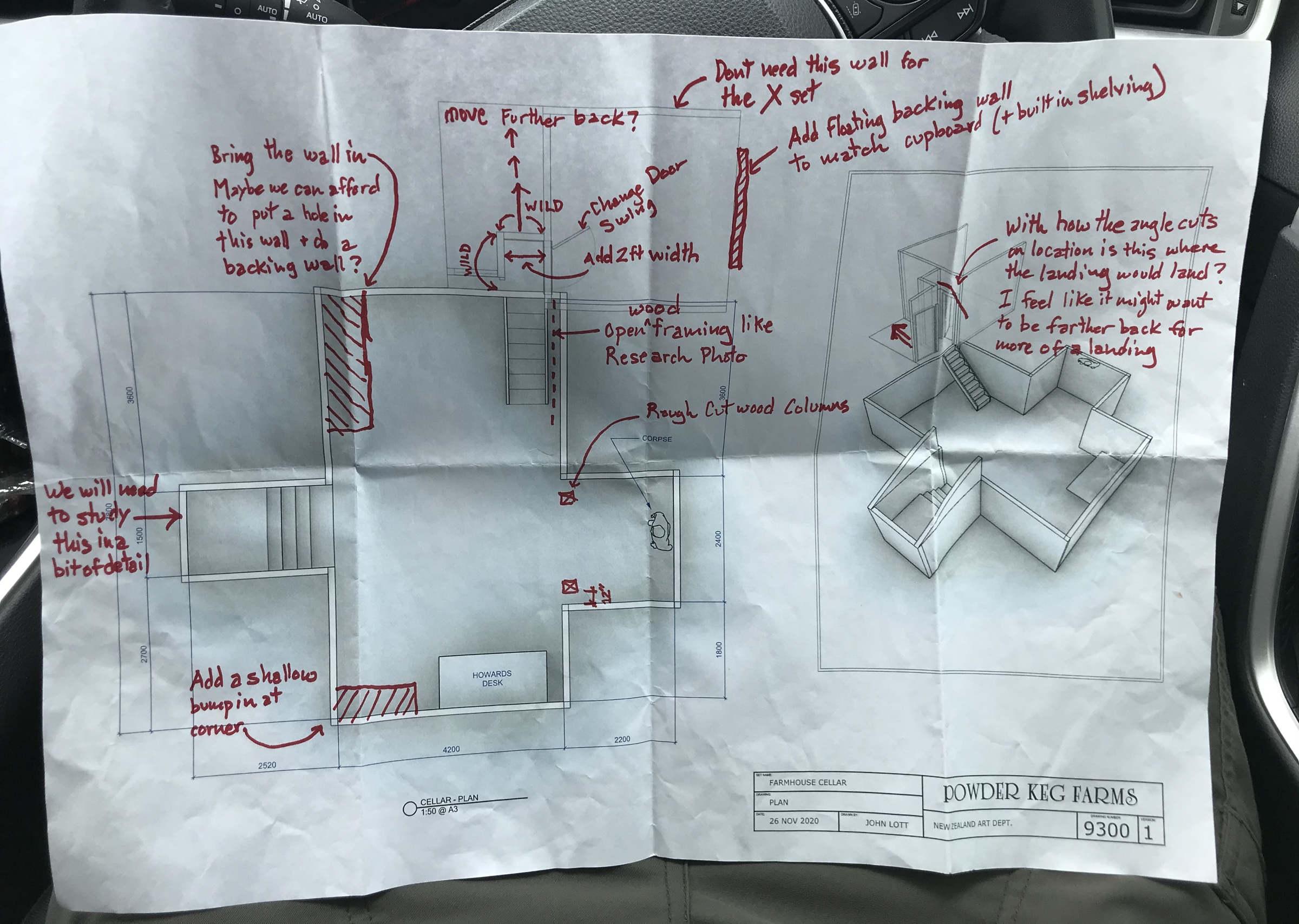

Diagram of the farmhouse cellar on “X” and “Pearl”, courtesy of Tom Hammock.

Kirill: Can you teach anybody to be not just a craftsman in the industry, but also to be an artist? Can you take anybody through an art school, and have them be an artist by the end of it – however you define what an artist is?

Tom: It really does depend how you define it. I’m always hopeful, and would like to think that you can take anybody, and teach them, and get them to a point where they can express themselves and bring their own backgrounds and ideas to bear on an artistic project in a way that maybe they couldn’t before. I do a fair amount of teaching on the side which is why I’m so enthusiastic about that.

Kirill: Is there such a thing as too many artists in the world?

Tom: Definitely not in the world. But sometimes on a project you have to narrow it down to a handful of people so that it makes it easier for the collective vision to come through – and then everybody can contribute in the way that they’re able to. Sometimes there can be too many ideas. I once worked on a project where there were two studios involved, and each studio was making a very different version of the project. That’s when things tend to go off the rails.

On the sets of the farmhouse cellar on “X” and “Pearl”, courtesy of Tom Hammock.

Kirill: You started in the industry about 20 years ago. Do you see much that changed since then in terms of where the stories are told, and the technology involved? If you jump back 20 years ago and then jump forward to today, is it much different or similar?

Tom: At its very base, it’s similar? You’re still trying to enhance character and create visual arcs in a story. And that’s never changed. You’re still trying to make the movie better.

Things are different on a more detailed and technical side. Back then, when I was shopping for a movie, I would be sent out with a Polaroid camera and a big stack of maps to go from thrift market to garage sale to rental house try to find whatever item it was for the movie. I would then come back with a big stack of Polaroid photos and spread them out and go through. That’s definitely changed, even as you’re speaking to someone who still has 10,000 feet of 35mm film sitting in his house, because I don’t necessarily want to give up the old ways [laughs].

There’s definitely been a change from hand drafting to a variety of 3D modeling and computer drafting during the course of my time in the industry. I still gravitate towards hand drafting myself, but there’s definitely been a lot of change. And then you also have the distribution aspect where you’ve had this change towards streaming television shows of various sorts, which is great. It’s more storytelling out there in a variety of different ways.

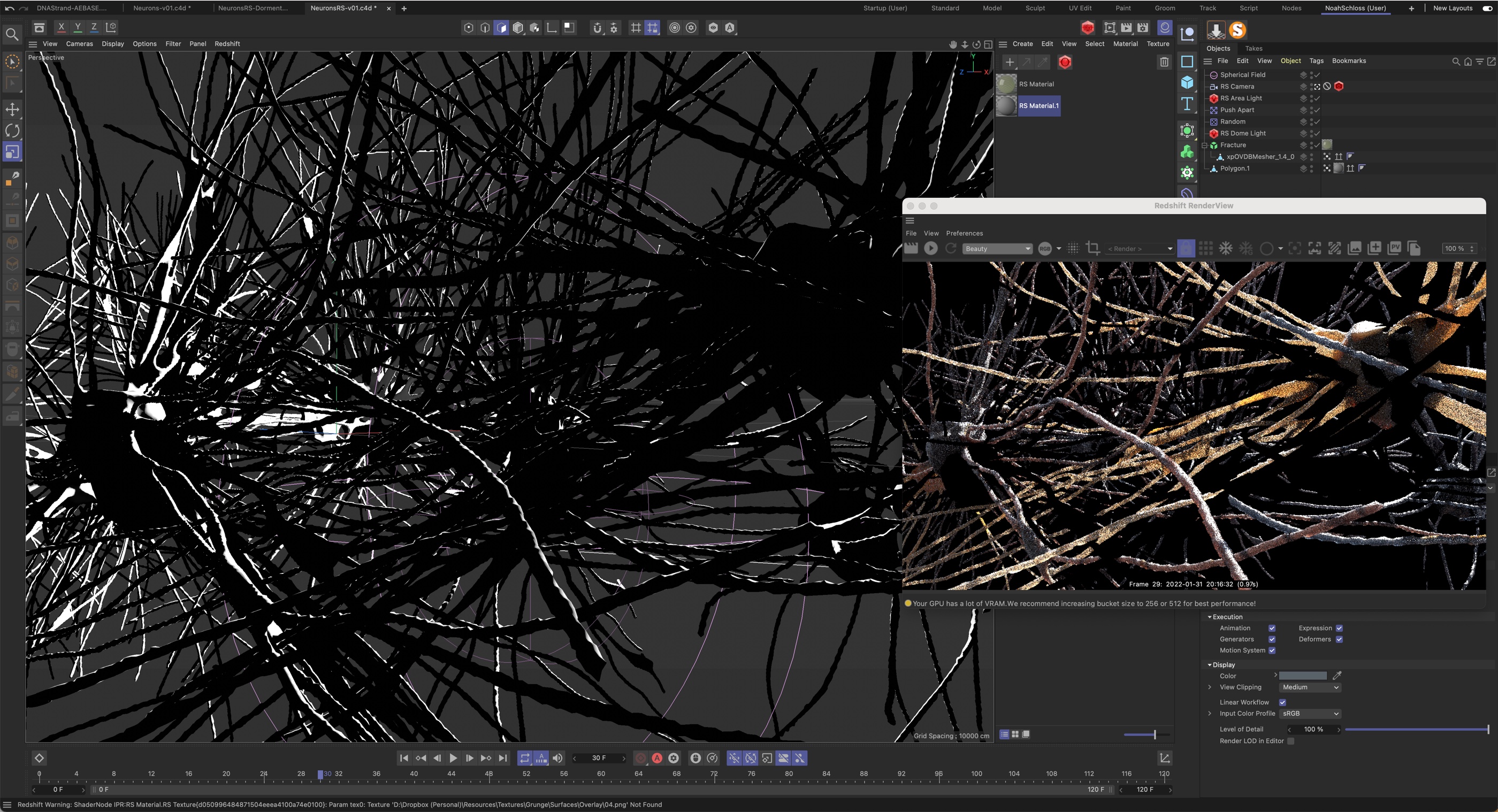

Production design of “X” by Tom Hammock.

Continue reading »

Continuing the ongoing series of interviews on fantasy user interfaces, it’s my pleasure to welcome Darby Faccinto. In this interview he talks about designing for the story, the difference between basic and simple design, the drive to learn new things, and the impact of generative AIs on human creativity. In between these and more, Darby talks about his work on screen graphics for “Loki” and “Black Adam”.

Kirill: Please tell us about yourself and the path that took you to where you are today. I love the bit you mentioned in the article on your alma mater website about doing Iron Man graphics when you were running for the high school class president.

Kirill: Please tell us about yourself and the path that took you to where you are today. I love the bit you mentioned in the article on your alma mater website about doing Iron Man graphics when you were running for the high school class president.

Darby: I’ve always loved movies and I’ve loved good storytelling. I remember when Ironman one came out back in 2008, and I was around nine. I had this dirt bike that I would ride around at my parents’ house. We had like a little farm, and I would ride it, and as I would wear my helmet, I would pretend to talk to Jarvis. I was a little kid, but I would imagine myself in the Ironman suit, hanging out and doing whatever.

That was probably how I got into this field on the subconscious level. I started paying attention to the HUD scene, and I thought they were super interesting. And then when I got to high school as a freshman, I thought to myself that maybe I could attempt to make a cheap version of this for this election I have coming up, that I would put a video on the school news and everybody will get excited. And I actually never was able to do it. I failed [laughs]. I made something, but I didn’t want to show anyone because it was so bad. It was like a shape layer with a couple of circles, but it was enough for me to feel like I could take it somewhere else. I felt that this was enough of an accomplishment to where I proved myself I can learn a new skill.

I didn’t know After Effects or any other programs. During that time I was Googling all this information about it, and that’s how I found Jayse Hansen. I reached out to him and I asked him if he could make an Iron Man HUD for my class election [laughs], and he said that he can’t, and gave me a link to a video tutorial to check out. That’s how I got hooked, wanting to make it better. I started going back and forth throughout high school and into college, taking a few months here and there, not doing it and picking it back up, and then trying it again – to eventually a point where I felt like I got really comfortable with it. And that was the beginning of Jayse encouraging me to maybe think about this career seriously.

Kirill: Would you say that a person needs to go through a formal art design training to get into this field, or is there enough information online for a determined individual to pull themselves by the bootstraps?

Darby: To be honest, the answer is both. I know a lot of people that I work with came out of Otis Design College. There’s plenty of great design colleges, but Otis is what I’m most familiar with. They have a great program, and a lot of studios snipe people out of there as they graduate and bring them in.

And I know a lot of people like me who have no formal design training at all. I was in college for something completely different, and I was doing this on the side of the hobby, and everything I knew was from YouTube or online. A lot of what helped me develop a strong taste for it was repetition and studying and comparing to what’s in film. Anybody can do that. If you have the drive and termination go out there and learn it, you don’t necessarily need to be in any formal training for it.

Screen graphics of “Loki”, courtesy of Cantina Creative and Darby Faccinto.

Kirill: There’s this rule of thumb that says that in order to get good at something, you need to put 10,000 hours into it. With everything being so accelerated now, do you feel that it’s still true in the age of the Internet?

Darby: From at least what I can attest in my field, you may not need 10,000 hours to learn the software. Maybe you can get comfortable with the toolset in a thousand hours. But then it would still take the other 9,000 hours or so to develop the taste, and I’m still developing mine.

I love blues. I love B.B. King and other old school performers. You’ll have this steady beat and there’s some quiet, and in between you’ll have tasteful guitar licks that are maybe four or five notes, but it’s a presentation. That’s how I see it for what I do. It’s important to master the tool set, but it’s more about what you are able to do with that to create that beautiful complete picture of what should be on the screen or how that moment should be told. And that comes in time. It’s not something that can be generated by AI.

Kirill: If you compare “Loki” to “Black Adam”, it feels that “Loki” elevated the screens to a bit more prominent place in the story. In “Black Adam” they were there, but they kind of existed in those spaces, but “Loki” made them hero elements. Maybe some productions do not necessarily promote or elevate the screen graphics to be these hero elements all the time.

Darby: “Black Adam” wasn’t necessarily about screens, and they were there to help tell the story a little bit more. But on “Loki” it’s a huge hero piece. It’s helping the audience understand the story, and that comes down to what am I working on and what is being asked of me. The graphics on “Black Adam” had a few story beat moments where they told a story, but for the most part it was there to help elevate the “futureness” of where they were. If we went over the top and made something absolutely crazy, that would have completely distracted from what the director wanted to get across, which was the moment between the actors, and not the screen. So in a way, that’s just as tasteful – to be able to restrain yourself and have something elegant that blends into what’s happening and does not take away from what’s going on.

Screen graphics of “Loki”, courtesy of Cantina Creative and Darby Faccinto.

Continue reading »

Continuing the ongoing series of interviews with creative artists working on various aspects of movie and TV productions, it is my pleasure to welcome Byron Werner. In this interview, he talks about balancing the art and the craft of visual storytelling, the transition of the industry from film to digital, choosing his productions, and what he considers to be a successful project. Between all these and more, Byron dives deep into his work on “Spinning Gold” that is hitting theaters tomorrow.

Kirill: Please tell us about yourself and the path that took you to where you are today.

Kirill: Please tell us about yourself and the path that took you to where you are today.

Byron: My name is Byron Werner and I work as a director of photography. I work in feature films, commercials, music videos, as well as a background in documentary, sports, television and other facets of cinematography.

I went to a Catholic school with a little closed-circuit television system, and that’s how I got interested in capturing images. Some friends and I would go write and make stories, and I was more interested in shooting. Shortly after that I got a video camera and started making my own little movies, and it kept going until I was in college. I applied to a few film schools, and ended up settling on Chapman University which is a film school in Southern California.

Once I got to that school, I realized that cinematography was the path that I wanted to take of all the crafts, or all the different job options. So once I did that, I did my four years and I tried to shoot as much as I could. I shot a ton of short films. I even shot a couple feature films, and just tried to build a reel and shoot as much as I possibly could.

After finishing college and trying to get a job as an AC or electrician, I started shooting, and I would PA a little bit on the side. I worked for a company at that time called Rap Patrol where they would hire us to come in and wrap big music videos. We would go and pull cable and clean up as they were shooting, and it was the hardest work you can imagine [laughs] – but I made money and I got to see all these giant music videos and these crazy big productions being made. I learned a lot and made a few bucks, and then on the side was able to go shoot movies for other people as a DP and kind of learn that way.

Kirill: How did the transition from film to digital treat you? Probably you started in the film only world and now it’s predominantly digital.

Byron: I started in the film-only world. I used to shoot a lot of really small, low-budget movies. I’d say my first 15-20 movies were on film, either 16mm or 35mm. We didn’t have a lot of money to buy a lot of film, so maybe we would get 20,000 feet of 35mm at a ratio of 1.5 to 1, so you had to be very judicious of what you shot [laughs].

At the beginning I didn’t like that transition. Film was such an amazing medium, and there was just nothing that came close to it. There was Panasonic VariCam back in 2001 which shot 720, and you had the Sony F900s, there was DV cams and then various digital cameras. And none of them were good enough. And it was hard to be able to use a real cinema lens. There were all kinds of weird ways that you’d have to find an adapter to use cinema lenses. It wasn’t a great transition when it started, but since then it’s been excellent when all these amazing digital cinema cameras have come out. Now there are so many to choose from.

I love film. Would I shoot film again? Sure, probably like riding a bike, I could do it. But do I need to? No. I love digital, I love seeing it right there, I love what you get, I love the cameras. I’m a big Alexa fan, but also from time to time I shoot RED or Sony Venice or Blackmagic. These cameras are amazing these days, and I really like digital cameras. I’ll also say a thing that may sound crazy, but sometimes film grain bothers me now. When there’s a little bit that we put on the digital, it’s fine, but when it’s really grainy – I don’t know. It’s not the same as it used to be. I like a cleaner image for the most part.

Cinematography of “Spinning Gold” by Byron Werner, courtesy of Hero Entertainment.

Kirill: You straddle the boundary between the world of art and the technical world. Do you think that anybody can be taught the technical side of it, and do you think anybody can be taught to be a good or a great artist?

Byron: I would think you could teach the technical side to anybody. It’s just something that you have to wrap your head around. I understand technical things in cinematography better than I understand physical things like construction, for instance. I can go into a computer or into camera menus and figure something out. But if you ask me to build something, I can probably do it, but it’s going to take me longer and it’s not as innate to me to be able to figure out the angles and figure out how it’s going to be done. I don’t picture it the way I do it with cinematography. But probably, if I spent a lot of time building things and got more experience, then I would learn how to do it. So I imagine that anybody can learn the technical.

The artistic side is a really interesting question. I always felt like I have a natural ability to see framing. I always thought that anybody could do it, but then I watched some friends or people frame something and it doesn’t really work, or it’s weird, or they don’t get the aesthetic of what it should look like or what is interesting. You can teach that to somebody, but there’s certain people – and I hope that I’m one of them – that the actual framing and the artistry is something that’s inside you and comes naturally.

Kirill: On the other hand, is it possible to objectively say what is good art and what is not?

Byron: I see that side of it, and the thing about art is whatever is good art often changes. If you look at cinema in the 1970s or even before from the beginning of cinema, it was not art to have a flare, and now it’s art to have a flare. It wouldn’t be art to have a lot of headroom, and now it’s art to have a lot of headroom.

And who’s to say what is art. I think that there are certain things that when you try to frame something or look at something or light something, that’s going to speak to people. And there are certain things that aren’t. Whatever you do is going to be considered art as long as it has intention, and has the intent of what you’re trying to do, the story you’re trying to tell, whatever you’re trying to have come across. Something that’s art and amazing to one person, may be just craft to somebody else.

You can claim you’re an artist by making art. Now whether you’re a good artist, that’s totally subjective as you said. But if you’re doing it and you’re making art, whatever that is, as long as you feel like it’s art, as long as your intent is to make something that yourself or somebody else can enjoy, then you can call yourself an artist – or other people would call you an artist. But then again, who cares, it’s just a title. It’s just a name. It doesn’t even matter, as long as you’re doing what you’re doing. If you’re lucky enough, in our case, to make films, then that’s all that counts.

Cinematography of “Spinning Gold” by Byron Werner, courtesy of Hero Entertainment.

Continue reading »

![]() Kirill: Please tell us about yourself and the path that took you to where you are today.

Kirill: Please tell us about yourself and the path that took you to where you are today.![]()

![]()

![]()