Continuing the ongoing series of interviews with creative artists working on various aspects of movie and TV productions, it is my pleasure to welcome Jesika Farkas. In this interview we talk about the beginning of her career in the field of architecture and interior design, the transition into the world of episodic television and feature films, building spaces for actors and collaborating with directors and cinematographers, and the challenges of working on small indie productions. In the middle of it all, Jesika tells the story of “Dixieland” – a movie that follows two characters in the underbelly of Mississippi.

Kirill: Please tell us about yourself and how you got into the industry.

Jesika: My background is in architecture and interior design, but I’ve always loved film. I was working for an architecture firm that sort of imploded, and I had a bit of time on my hands. My brother was in industry doing storyboarding, and he was approached to design a short. He wasn’t able to do it at the time, and he put them in touch with me. That was in 2010.

I always loved the concept of visual storytelling, and I accepted the gig. It was “Mother’s House”, the first production I designed. It was a nine-day shoot with some really lovely people, Ingrid Price and Davis Hall who wrote, produced and directed it. And from there it catapulted into the field, and since then I’ve been doing feature films, TV and shorts.

Kirill: Was there anything surprising when you joined this industry that was new for you?

Jesika: This actually happens quite a bit. I live in New York and I split my time between upstate New York and New York City. There’s a firm called “Roman and Williams”, and that couple actually started off in the film industry. They did a bunch of films with Ben Stiller, and wound up designing his house. From there they made a switch to the other direction and now they have a very established and reputable architecture / interior design firm.

And sometimes it happens in the reverse direction. It’s the visual medium that you’re playing with. There are spaces, and you’re conceiving of them. It can be for actors to come through, and they’re constructed in a way that lasts for a temporary moment. Or it can be for more permanent enjoyment. But they have a similar goal that you’re going after.

It was a very easy transition for me to take up film and create the environments that help to tell the story. In architecture you’re designing things that last a lot longer, but they might not have as much playfulness or creativity going into them. I actually still do a little bit of that as well, straddling the two worlds of reality and film.

Concept artwork for “Dixieland”, courtesy of Jesika Farkas.

Kirill: If you asked me twenty years ago how movies are made, I’d tell you that somebody puts a camera on the shoulder, points it to the actors that happen to be in some existing space, somebody shouts “Action!” and that’s it. But that’s not as simple. Everything needs to be designed, to create environments that tell the story visually.

Jesika: Absolutely. It’s very much a collaboration between the production designer, the director and the director of photography to conceive of a space. It always starts with a palette and feeling of the film, and being able to visually convey what is needed for the story. You work with that. But it does seem like it could be quite easy.

But ultimately if you really want to convey something fluid and you want to support the story, it needs to be designed. And you don’t even notice that. Sometimes it can be very much in your face, but it can also be very subtle. There’s needed intervention in the design process, for sure.

Kirill: What is your experience with episodic television so far?

Jesika: A lot of it is done on a soundstage. You wind up building the primary set, something that you come back to time and again. And you fill in with locations to give everyone a break and be able to diversify the visual element of the whole series. But the anchor is the staged set, and it can be quite different from independent films, where staged sets are an afterthought. There you’re really out in the field shooting and making locations work.

For episodic television it’s often a very planned larger set that you curate and build, and it’s a basecamp that you come back to time and again. That becomes the anchor of a series.

Kirill: Is that a production consideration that you have however many episodes in the season, and you can’t close down a particular location for an extended period of time?

Jesika: That’s right. Your set is there on the sound stage, and it might be sitting there with nothing happening when you’re out in the field on the various locations.

Kirill: Do you have a preference between working on location and on stage sets?

Jesika: If you go back to earlier film days, everything was on a stage and everything was controlled. You think of old Hollywood, you think about giant cavernous place where you could create SPRAWLING sets and everything was at your disposal. But of course it’s a very costly thing. This is where finding locations helps.

You wind up working with those spaces, and transforming them sometimes or just leaving them as is and going with the feeling. That depends on being able to find a location that suits your need. I think there’s an advantage to shooting on a stage for sure. You can create everything exactly as you want it to be. And there’s also an advantage to being on location and finding things that are already existing and beautiful. You have the ability to invite natural daylight into spaces and just augment that. You see the passage of time in those spaces, and find things that are sometimes difficult to recreate.

Continue reading »

Continuing the ongoing series of interviews with creative artists working on various aspects of movie and TV productions, it is my pleasure to welcome Dan Laustsen. In this interview we talk about Dan’s work on one of the most visually striking films of 2016, “Crimson Peak”, as well as about the transition from film to digital, different ways to convey suspense and horror, minimizing disruptions on set for the actors, and the magic of making films.

Dan Laustsen on the set of “John Wick: Chapter 2”. Photography by Niko Tavernise.

Kirill: Please tell us about yourself and your path so far.

Dan: I was born and educated in Denmark. I studied set photography, and when I was 21, I was bored with it. At that time I went to the Danish Film School to study cinematography. I’ve spent three years there, and after graduating started working on my first feature film straight away at the age of 25. Nobody in my family has anything to do with filmmaking, but I am very happy about being here.

Kirill: Has much changed for you in your field over the years?

Dan: Telling a story is the most important thing that we do. That’s the basis of everything that you do. You work with the script and you paint with light.

In the old days we shot everything on film, and things are getting faster and faster now. The equipment is getting better. At the beginning of it I was against digital. I didn’t like the look, but that has changed after a while. We did “Crimson Peak” on digital, and I was very pleased with the look. Alexa is doing a fantastic job with its cameras.

It’s easier to see what you’re doing. In the old days you had the magic of capturing the image on camera, and that’s disappearing. It’s a shame because you were not totally sure how it was going to be, and you had to wait for the lab to process dailies. All that disappeared, but I’m not afraid of that. It works fantastic and helps with what we do, which is to tell a story in the way we want to.

The lenses are getting better, and I’m very much for that high quality that it brings to cinematographers. I don’t go for old-fashioned lenses. I’m using the high-end equipment as much as I can.

Kirill: While that magic is gone, on the other hand everybody can immediately see what the camera sees. That must be creating a tighter feedback loop for fixing whatever issues crop up on the set.

Dan: For sure, and that’s good. Everybody has opinions, and I think the most important part is for the director and the cinematographer to work together. Everybody on the crew works together, and it’s much easier now. We have high-quality video monitors on the set, and everybody can see small mistakes and fix them right away. But the magic of movie-making has disappeared. It is what it is, and I think it’s helping everybody.

Kirill: Do you think it’s becoming easier for people to get into your field, as the equipment for shooting and editing is becoming cheaper and more widely accessible?

Dan: I’m sure it is. You can shoot with an iPhone or a small camera. Everything is about the story, and it’s much easier to tell those stories now for younger directors. You don’t need to spend a lot of money on labs, for example. You don’t have to be afraid of anything any more, and that gives a big push to everybody.

Kirill: What makes people still go with film as a medium?

Dan: You’ll have to ask somebody who is still shooting on film. People are shooting on 70mm, and the quality is amazing. For me personally, digital is doing a fantastic job. You can get a bit nostalgic about it. I’ve shot feature films on 45mm, and I was very much against digital at the beginning. But what we’re getting now from digital is fantastic in my opinion.

You still have to light the scene to tell the story in the right way. What I like about making movies these days is that there are no rules. You can do whatever you would like to. In the old days you had so many rules about what you could and could not do, about lines that you could not cross. All those rules have disappeared and that’s so good. You can tell a story in exactly the way you want.

Continue reading »

Continuing the ongoing series of interviews on fantasy user interfaces, it gives me great pleasure to welcome Derek Frederickson of Twisted Media. In this interview Derek talks about his early days in mid-1990s experimenting with Flash on the web, the screen graphics work his company has been doing on numerous episodic cable shows in the last ten years, and the software tools he’s using and how he would like them see evolve in the future. In between and around, we talk about his work on the recently released “Independence Day: Resurgence” that bridges the world of 2016 with the alien technology left “behind” in the first installment in the franchise, as well as glimpses of Twisted Media’s work on the upcoming “The Space Between Us”.

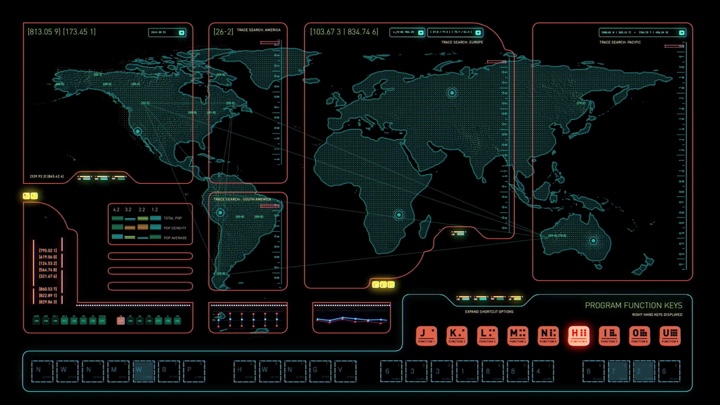

“Independence Day: Resurgence” Area 51 monitor test. Courtesy of Twisted Media.

Kirill: Please tell us yourself and how you started in the field.

Derek: I’ve been doing the things that I do today pretty much my whole life. I’ve always been interested in design, programming and animation…and that’s exactly what you need to able to do work in this field. Back in the early ’80s when I was in my single digits, I had a TI-99/4A. I went to school to study video production, and that helped with certain aspects of shooting, and understanding the whole flow of writing, capturing an image and editing. I was also a musician, so I have a lot of audio experience.

These three things combined helped me ever since. In the early ’90s I was doing CD-ROMs, designing interfaces, interactions, movements – a combination of all of those elements. And that’s still what I do now. If we do a command center or some sequence on a phone, it’s an interactive thing.

Derek and Tony on the red carpet premiere

Derek and Tony on the red carpet premiereThere’s an interesting thing about me deciding to name my company Twisted Media. It was just me, doing freelancing from time to time. And I got a random email from the assistant to Mark Franco who was the VFX producer that worked with Dean Devlin a lot. They were doing a show called “Leverage” and they were coming to Chicago, which is where I was living at the time, to do the show. And they literally saw the listing for my company in a creative directory and liked the name.

They asked me if I could do graphics for a TV show, and I was so excited after looking up the list of productions they’ve worked on, that included Independence Day and Stargate. So I wrote back “Yes, I can” [laughs]. That’s how it started. When Dean interviewed me, he knew that I was new to that field. But he also knew that the stuff that I showed him was very close to it. He recognized that I could do what was needed. And when he asked me if I could do that, I told him that I had waited my entire life to do it. I’ve worked on a lot of productions since then, and I’m now back to working with Dean on “The Librarians”.

Screen graphics for TV show “Powers”. Courtesy of Twisted Media.

Kirill: If you look back at 2007 when you started working on “Leverage” and your work since then, do you see any big changes in what productions expect from what you do?

Derek: It depends on what kind of a show it is. If it’s a show that takes place today, there’s been such a huge shift in our everyday lives. You look around, and no matter where you are, people are looking at their devices. So for these shows, art is imitating life.

There’s an interesting difference between the shows back then and the shows that are made now. A lot of these shows deal with the world of social media, where you can track somebody’s activity based on what they posted on Facebook. These things are mature and established, so there’s not much creative design or inventing how it looks. There’s still work to be done, but it’s such a mature playground now.

Everyone sort of knows what it looks like. We know the interfaces of Facebook and Instagram and Twitter. They are well-established. You are asked to show a character being on a social media, but it can’t be the actual thing. It is limiting, because we all know how that “looks like”. It’s not reinventing the wheel, but rather coming up with a creative way to do it. And oftentimes it looks a little weird. It’s just text on the white background [laughs].

We grew up with this in the last decade or so. This affects everyone’s lives. Consequently, when you design for it, you can’t take the viewer out of the moment and you have to take those well-established elements. You have to work with the parameters of what has come before and has been accepted.

Screen graphics for TV show “Scorpion”. Courtesy of Twisted Media.

Kirill: Is that due to production restrictions of not being able to use those branding elements without explicit permission from that company?

Derek: The clearance department is always the bane of our existence. They have to look at everything. You can’t use real usernames, for example. Everything that we make is fake. Oftentimes we call it Fakebook, because it can’t really be Facebook. We do work for “Empire” that has a lot of music gear. There’s a program that they use, and it looks a lot like ProTools, but it’s not. It’s FauxTools [laughs]. Everything has to be vetted. The design of it is copyrighted and owned property.

In a sense, working on something like “Independence Day” is so liberating. It’s not in a real world, and you can explore and make something, and it has nothing to do with today. You’re really creating a new world, and that’s where you can stretch your wings and do some neat stuff.

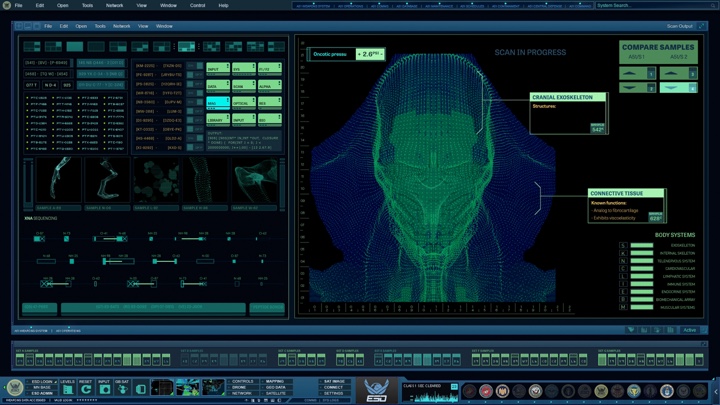

“Independence Day: Resurgence” alien biology research, head, interface. Courtesy of Twisted Media.

Continue reading »

Continuing the ongoing series of interviews with creative artists working on various aspects of movie and TV productions, it is my absolute delight to welcome Natasha Braier. In this interview we talk about the art and craft of cinematography, the hierarchical structure of feature film productions and how that structure still lends itself to predominantly male voices, and the pleasure and pain of working long hours over months at a time. The second half of the interview is on Natasha’s work on the meticulously crafted “The Neon Demon”, an engrossing story of a young girl taking her first steps as a fashion model in the wild urban jungle of Los Angeles.

Natasha Braier on the set of “The Neon Demon”. Courtesy of Natasha Braier.

Kirill: Please tell us about yourself and how you started in the field.

Natasha: I was doing still photography when I was a teenager. It was mostly black-and-white, developing them in my own dark room. The first time I looked at the end credits of a movie and saw the title of director of photography was when I was nineteen. I was immediately interested in that, and some of my older friends who I studied photography with had chosen to go to film school. It was through them that I discovered that world and the role of a cinematographer. That’s when I decided to go to film school myself.

Kirill: Do you remember being surprised at anything in particular when you started there, when you saw how things worked behind the camera?

Natasha: I wouldn’t say that I had big surprises. There were a lot of things to learn that were different from the world of still photography. If there’s anything that I didn’t know at the time I made the decision to go to the school and go down this career path, I’d say that I didn’t know that it would be such an intense commitment. You barely have time to have a life, and I didn’t know that I was going to spend so much time traveling and working away from home.

Also, I didn’t know that you could make so much money as a cinematographer. That was a nice surprise. I thought that I was going to be a humble artist doing what I love, much like other artists that I saw in my life. It was a good surprise that I get to travel the world and see all the exotic places, and make money. And the other surprise was that if you want to be home for a few months, that’s difficult.

Kirill: Looking back to when you were in school, what happened to people that went to that school with you? Are most of them still in the field, or do some leave it as years pass by?

Natasha: I went to a couple of film schools because I was moving with my family. I only stayed a few months in Argentina and another few months in Spain, and then I spent three years getting a master’s degree in cinematography in England. That’s the only education that I completed end to end.

That program was very selective, accepting only six people every year for each field. The other five that started studying cinematography with me that year were older than me, in their late twenties and thirties. Some had been camera assistants before, and they were really committed to this work. It was difficult to get into that school, and once you got in, you continued afterwards in the industry. Some had more success than others, but all of them are still working in the field.

Kirill: As you said, your job is quite intense, and you spend long months away from your family and friends, and long hours on set once the shooting starts. If we’re talking about you, what makes you stay in your field?

Natasha: It’s a great job and I love doing it. It comes with a cost, and otherwise it would have been a paradise. You pay a price. You have your freedom – you don’t go to the same job every day, you don’t have a boss, you get to choose your projects, you get to travel and meet different people. And the price you’re paying for that freedom and flexibility is that you don’t always know what you’re doing next month.

I think the world is divided into people that can live with that and people who need a stable life and a stable job. If you’re not the former, you will probably not stay in film industry. If you talk about people in the industry, we are not very normal [laughs]. We need the adrenaline and the highs. It’s like being on a rollercoaster. You have your ups and downs. That’s the challenging part of the work.

Over the years I’ve learned to deal with that in better ways, to not get so anxious about what I was going to do next, and to trust that there’s always something coming. I started enjoying the moments when I’m working a lot more, and to stop worrying about what’s next. It’s also a big spiritual test where you need to learn a lot about patience and not having control over what’s next.

Continue reading »

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()