Continuing the ongoing series of interviews with creative artists working on various aspects of movie and TV productions, it is my pleasure to welcome Carolina Costa. In this interview she talks about technology changes in the field of cinematography, discovering new voices as a viewer, the balance between technical and artistic aspects of her craft, and how she chooses her projects. In between these topics and more, Carolina talks about her work on this year’s “Babenco” and “Hala”.

Carolina Costa on an AFI Panel at the Sundance Canon Creative Studio.

Kirill: Please tell us about yourself and what brought you to where you are today.

Carolina: My name is Carolina Costa and I’m a director of photography. I’ve done documentaries, commercials and music videos, but I really like to focus my work on narrative fiction work. It’s interesting because it takes me back to when I first started as a journalist.

I’m originally from Brazil and I’ve been moving around the globe. I lived in England for a few years, then in Los Angeles and now I’m in Mexico. Back when I was in Brazil, I studied journalism and I worked as a photojournalist. Still photography was my first contact with the world of capturing image – I was photographing the reality around me. I grew up in Rio, right next to one of the biggest favelas, and it’s a violent city. My first interest was to portray the kids around the area.

Moving into motion pictures came from that as well – through the frustration of not being able to change my environment. I felt like movies could do that, more than what I was doing with photojournalism. I felt like people could go to the theater and forget how bad their lives were, or they could go and connect to a character on the big screen and through that experience they could deal with something that is a little harder in their life.

When I first moved to London I started working as a camera assistant. Then I moved up the ranks of the camera department and eventually graduated to being a director of photography. Then I went to do my Master’s degree at the American Film Institute, and that was the moment I saw myself as a director of photography with all the necessary tools.

Kirill: Is there anything in particular that you remember from being on set in your first couple of productions?

Carolina: The other day I found the photos from the first film set I worked on as a camera assistant, and I looked so serious. I think I was just nervous, trying to do a good job. I knew it was going be a long way to the top, with long hours and very little sleep. You’re fighting for a piece of the spotlight, because there’s so many good people out there.

It wasn’t glamorous or anything. It was quite clear to me that it was a lot of hard work. When I started as an AC, the days were long and the nights were short. I’d catch a train then a bus, and would be the first one on set to clean everything. I’d sleep maybe three hours every night. There were days that I would question what I was doing, but it was clear to me that I wanted to be there.

I always tell people who start working with me, that you need to know if you really want to do this. There’s zero glamour to it [laughs], and it’s a lot of hard work. But I feel that if you truly have that passion, there’s just nothing like it. When I’m on set I’m truly myself. When I’m outside of set, sometimes I find it hard to find my footing. That’s also part of the experience. You accept the little sleep and long hours.

Cinematography of “Girl on the Side”. Courtesy of Carolina Costa.

Kirill: Do you think it’s easier to get into your field these days, as cameras are getting better and cheaper, and some people even shoot things with their phones?

Carolina: That’s really exciting. When I first started shooting music videos and shorts, it was right around the time when 5D, 7D and similar cameras came out. That new equipment had shallow depth of field and it was affordable. It gave freedom to someone like me that couldn’t go and shoot a short before.

Previously you would need to go to Fuji or Kodak, and beg them to give you some film. Then you’d go to a lab and try to persuade them to process it for you. One of my early shorts was done in a lab as a back-end of someone else’s production.

I remember that period when those cameras came out. I went out and experimented with shorts and music videos, figuring out how to light and do other things. That is still going on today. You can go with your iPhone and shoot something, and it is valid.

With all this talk about digital taking over, I thought that maybe voices we haven’t heard before would now be heard. Where I come from, the famous movies are all about the slums and the violence in those areas, but generally you never see a movie that is made by someone actually from that place. It’s usually middle class and upper middle class talking about those social circumstances.

That’s what excited me most about those cameras becoming accessible. I was looking forward to those new voices coming out. But very little is coming out of it, and I can’t put my finger on why. You have more cameras and they’re cheaper, and people can experiment, but I still feel that it’s an industry that is reserved for very few people, and that hasn’t changed. I wish the excitement about the new digital format had pushed the other side as well, but it hasn’t really. I feel like it’s a shame, because it offers that possibility.

Recently I saw a guy here in Mexico and he sent me a cut of a documentary he shot on his phone. It’s crazy. He filmed real narcos, and he was right in the middle of it with the guys, the guns and everything. I haven’t seen anything like it. Of course, there’s no way you could bring an actual film camera and lights. We talked about how he could make the cinematography better and more interesting, but I told him that he shouldn’t listen to me. He should go and do what he’s doing.

It’s generating interesting projects and I wish there were more of them.

Kirill: From my perspective as a viewer, sometimes I ask myself how do I discover those new voices. It can feel a bit overwhelming and fragmented to navigate the landscape of visual storytelling, be it features, documentaries or shorts. How do you go about it as a viewer?

Carolina: I suffer like everybody else. We see the same billboards and the same posters. I feel like everybody watched “Roma” because there was so much advertising for it [laughs]. You couldn’t miss it, it was stuck in your mind. I’m human, and I’m part of the same society.

I have friends in many places in the world. The other day I sat down with a friend from Iran, and I asked them to give me names from Iranian cinema. Then I spent the whole weekend watching their work. Afterwards, I reached out to friends and colleagues from different places, cultures and upbringings. That’s how I find things to watch.

I’ve also been doing master classes, and I feel that the contact with younger generations has exposed me to a bunch of cool stuff that I would not necessarily be in tune with.

Cinematography of “How To Make a Bomb”. Courtesy of Carolina Costa.

Continue reading »

Continuing the ongoing series of interviews with creative artists working on various aspects of movie and TV productions, it is my delight to welcome Natalie Bronfman. In this interview she talks about what costume design is, creating a subconscious expression through color and shape, the meaning of color and how it carries across culture and time boundaries, and her approach to creating costumes for characters in stories she works on. Around these topics and more, Natalie dives deep into her work on the meticulously designed third season of “The Handmaid’s Tale”.

Kirill: Please tell us about yourself and what brought you to where you are today.

Natalie: Originally I wanted to be an opera singer, but even though I was good, I wasn’t the best. I already knew how to draw and sew, and I tried to figure out how I could stay in that environment. I ended up studying costume, first through fashion & costume at school, I did a few runway shows and then going to costume in theatre & film.

Natalie Bronfman with a Gold-leaf

Redingote at MFW 2018

I started making theater costumes when I was about 12 years old. In high school, I made prom dresses for other girls [laughs] as well as for any plays that we had. I started to study costume at Parsons in New York City. It was predominantly a fashion program which I didn’t really love as much as costume which I wanted to specialised in, and so I found another school in Rome, Italy. I already spoke three languages, so I learned a fourth one. Much of opera is written in Italian, and it was good to understand what they were singing. The language is so lyrical as well.

Kirill: How did you end up in the world of screen story telling?

Natalie: In theater studies you learn costume and sets, from blueprints to completion. When I graduated, I worked doing interiors for a while. I had big clients, many of them multi-million dollar projects, and with that comes a daunting payment schedule. You pay your crew, but you yourself are not being paid very much, or sometimes you have to wait 90 days. It wasn’t a sustainable way of living.

I applied at IATSE here in Toronto, and the next day I got called. I started from the bottom, and worked my way up. I’ve done all the positions in the costume department.

Kirill: Is there still anything surprising or unexpected that you come across when you join a new production?

Natalie: Every production is new. I love getting a new script. “The Handmaid’s Tale” is a phenomenal project. It’s one of the true design shows that I’ve ever worked on – everything built from scratch. It is rare, mostly because of the budgets that we have to work with and often the time factor. If you’re given very little money or very little time, you have no chance to build anything.

When I tell people what I do for a living, they have a different conception of what it actually is. A lot of it is psychology, more so than design, particularly because you’re dealing with actors. Not only are you dealing with the actors’ personal but also the psychology of the character in the story and you have to meld the two to become symbiotic.

I think that was what surprised me – how many other things I have to know, how much I have to delegate and how much I have to converse with people besides actually designing. I would say that it’s almost 80% of it; that’s what surprised me most when I started in this business.

Costume design of “The Handmaid’s Tale” season 3. Baptism ceremony, outside.

Kirill: Staying away from “The Handmaid’s Tale” for a minute, do you find that people do not understand the complexities of costume design, especially in current-day productions? We wake up, we throw some clothes on and it feels a rather organic part of our lives. Probably not a lot of people invest time into thinking how they’re going to express themselves today.

Natalie: Many people have an opinion. That is good, but you have to figure out whose opinion you must follow. You can’t follow 10 people, so you have to narrow that down.

When you’re doing the costuming of a character, you have to be able to understand at a glance, where they are mentally, economically and socially. You have to capture all of that essence and clothe the person, so that in a nano-second you understand who they are.

Colors have a meaning. Shape has a meaning. Fabric itself has a meaning. You should be able to tell if this person is sad or depressed, is he a bad guy or a good guy. There are cliches as well that you sometimes have to follow, depending on the story. I usually try to think outside of the box though, because you want to surprise the viewer and keep them interested.

Kirill: Do you find that meaning of color, shape or texture translates well across cultural boundaries?

Natalie: It depends. In Asian culture, the color white is used for mourning. You must be knowledgeable of those cultural things, depending on what sort of the clientele or project you have. Purple is a big color in every culture, and it means something slightly different in different cultures and different parts of the world. One should study these things and be aware of them when planning a project.

We have big ceremonies in our lives – benedictions, marriages, deaths. Colors that are worn in these big events also influence our everyday lives. For example, it used to be that women would wear black when their husband passed away for the rest of their lives, but only in certain cultures. So again, it depends on the story and time era as well.

Costume design of “The Handmaid’s Tale” season 3. Baptism ceremony, inside.

Continue reading »

It starts as an idea on a piece of paper, a figment of an imaginary world, a sketch in a notebook. A tender, fragile seed with just an inkling to how beautiful its blossom might be. It takes dozens, if not hundreds of hands of skilled craftsmen to cultivate, grow and nurture that idea over a period of long weeks and months. This is the craft of an art director – take that sliver of a fantasy and create a physical manifestation of it that is believable for the director, for the actors and, most importantly, for the audience – be it a music video, an awards show performance, a theatrical play, a feature film or an episodic TV production.

Continuing the ongoing series of interviews with creative artists working on various aspects of movie and TV productions, it is my pleasure to welcome Adam Rowe. In this interview he talks about what art direction is, the glamour and the grunge of Hollywood, the evolution of storytelling in episodic and streaming productions in the last few years, and what keeps him going . Around these topics and more, Adam dives into his work on “Rizzoli and Isles”, “Mad Men”, “Parks and Recreation”, “Forever”, “Criminal Minds”, “The Good Place” and his most recent “Rent: Live” for which he has received the Emmy nomination for outstanding production design for a variety special.

Kirill: Please tell us about yourself and the path that took you to where you are today.

Adam: First of all, I’m excited that you do these interviews. I do think it’s pretty exciting to hear everyone’s story. I hosted an event a couple years ago for the Emmys where we talked with several production designers and set decorators to hear their story, and how they made certain shows. It was fascinating. So many times there is emphasis on producers, directors, writers and actors, and it’s not that they’re not worth emphasizing, but it is so great to hear how things are made. Makers often have wonderful stories.

I was looking at some of the other people you’ve interviewed and it seemed like there’s a theme often that people see something, at an early age, and get inspired. I was the same. I saw “The Who’s Tommy” musical that toured in Chicago. That was definitely influential. For me a spark came from the stage, and I thought about whether I become someone in the theatre. Or, do I become an engineer.

My grandfather designed the air-conditioning for the Pirates of the Caribbean attraction in Disneyland, and that’s the closest to the entertainment industry my heritage comes [laughs]. My mom worked for an engineering firm. My dad had an excavation company that did a lot of roadway and water mains. He was also a farmer. I grew up in the middle of Illinois and access to the arts wasn’t necessarily a number one priority, especially at that time in the early ’80s.

Our library closed at my grade school. We were also without a music program for quite a while. There certainly wasn’t any kind of dramatic arts program at Grand Ridge, Illinois. A tiny little town of 200-300 people. It took, you know, a lot of effort in my high school and college days to explore working in the theatre and arts.

Art direction of “Rent: Live”. Courtesy of Adam Rowe.

I was a scenic artist first. I painted opera floors for the Santa Fe Opera and backdrops for the beloved Seaside Music Theater in Florida, which no longer exists. Then I traveled around, living out of my car for quite a while. It was difficult, with family, community and just life, because I was moving around so much. I decided to give Los Angeles a try based on a friend’s recommendation. I moved here in 2006 and I haven’t really looked back.

Television kind of absorbed me at that point, mostly because of the quickness and the excitement. The idea of a TV show as a rising phoenix. These things come together. There’s so many people and so many ideas. We make something and then there’s that idea of letting it go. I actually enjoy that.

Of course I’ve become attached to certain shows, sets, people, stories and characters. But there is something beautiful about the end of something. A set or whole world going away and then making something else completely new. But, it’s on film you can always return it if you wanted. If I didn’t enjoy that sense of quick renew, I think that it would be a better place to be working in theme parks, or architecture or interior design where they have projects that last longer.

Committing to television is more of a recent development in my psychology. Getting my career started was the focus, and I didn’t really care what I was working on necessarily. I’ve had a unique career and I’ve bounced around a lot. I’ve done still print for advertisement in the early days of my career. I’ve done game shows, one-hour drama, half-hour comedy, live events and even a night parade for Universal Studios Japan. It has been circuitous, and I’m curious to know people think about that.

Some people ask me “How do you do that,” meaning bounce around. For me it’s all quite similar in the sense that you’re making something for an audience. You just have to figure out what that something is, and what would excite that audience.

Kirill: Thinking back to your earliest TV productions, how glamourous did you think it would be, and how perhaps less glamourous it ended up being behind the scenes?

Adam: I didn’t know or think a lot about that when I first started. I came up through the theater world, and it’s very dirty. Theaters often put their artists in closets, basements and hallways, and in the case of the Seaside Music Theater, in an airplane hangar in the middle of Daytona Beach Florida, without air conditioning. We used to spray the ceiling with a garden hose so that it would drip down on us, so that we could stay cool while we painted. There was no glamour in that, but then all of a sudden you get close to opening night and you get invited to an opening night party, and you have to quickly scrub all the paint off your fingernails and go get dressed up. That was the extent of it.

Art direction of “Parks and Recreation”. Courtesy of Adam Rowe.

My first television job that I have such strong memories of was the first season of “Mad Men”. I worked in the art department, and the thing that struck me that was just so glamourous was that they had lunch every day [laughs]. The stars of the show were not super-stars yet. Elisabeth Moss, Jon Hamm and Christina Hendricks became famous on that show, and they obviously had names before. But I remember that on season one we sat around the tables together, and you sat next to Jon Hamm and Christina Hendricks and it was really cool.

Dan Bishop the production designer is an incredible teacher, and Christopher Brown the art director helped me grow and learn a lot on that show. As far as the glamour was concerned, that show looked it. It was very glamourous. The sets were beautiful, and it was a clean, friendly, wonderful work environment. Matthew Weiner created a compelling show and Scott Hornbacher, a producer, kept a tight, organized ship. It was such a wonderful place to work.

It grew into its glamour. When that show came out and it started to get famous and continued into the total of seven seasons. It developed with its glamour. Go back to its delicious first episode and see how it grew.

For me the most glamourous was the surprise that they would have lobster and steak catered for the final dinner. I’m not sure they did that every season, but I would guess they did.

There’s something fun about the television and movie industry having a lot of celebrations. I’m nominated for an Emmy this year, and I’m super-pumped and excited about it. There’s a party for the Emmy nominees. There’s a party that the set decorators are putting on. And then there’s of course the creative Emmys, and they all require different outfits [laughs].

That’s a pretty high, glamourous thing and the underside of that is you can still work on shows where they put the art department behind a pawn shop in Hollywood. So it hasn’t changed that much from an airplane hangar [laughs]. It depends on the show, and it depends on who’s running it.

Art direction of “Rizzoli and Isles”. Courtesy of Adam Rowe.

Continue reading »

Continuing the ongoing series of interviews with creative artists working on various aspects of movie and TV productions, it is my pleasure to welcome Gonzalo Amat. In this interview he talks about technology changes in the field of cinematography, set dynamics and collaboration through communication, finding the balance between technical and artistic aspects of storytelling, and the world of episodic productions . Around these topics and more, Gonzalo dives deep into his work on “The Man in the High Castle”, alternate history of post-World War II where the Axis powers have divided the United States and assimilated the citizens into different cultures.

Kirill: Please tell us about yourself and the path that took you to where you are today.

Gonzalo: I watched a lot of films since I was little, but I didn’t really ever think about working on film as I didn’t know you could have that as a career. But I did have a still camera throughout my school years, and I would take photos everywhere. As I was getting closer to college age, I started getting interested in literature and storytelling in general.

When I was in college, I started out studying communications, and didn’t get to film until later. It slowly came together, as you take novels as narrative, and add visuals through photography to make a film. I started working in productions as a production assistant, and when I was sure that it was what I wanted, I went to the London film school. After that I moved back to Los Angeles where I studied in the American Film Institute, and I’ve been shooting since – everything from documentaries to art films, from short movies to TV and streaming.

Kirill: Looking back at your early days in the industry, was there anything particularly surprising or unexpected for you?

Gonzalo: A set is always such a weird place to be on. I’ve been there for half my life already, but I still think it’s a very strange place. Everyone is always running around, and then suddenly everyone stops and it’s complete silence, and then everyone runs again. It’s this kind of mix of energy that’s interesting and focused. There’s really nothing like it.

It’s so special to see all these people, each one doing their own job, and everyone comes together. Then, when you roll camera, everyone quiets down and you have all this energy concentrated into one small space that goes through the camera. The energy on the set still surprises me to this day.

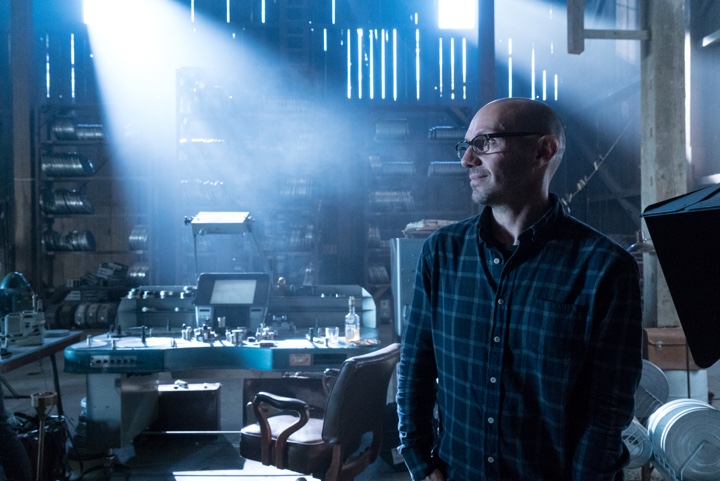

Behind the scenes on the sets of “The Man in the High Castle”. Courtesy of Gonzalo Amat and Amazon Studios.

Kirill: Now that you’re working in the industry, how does that affect you as a viewer? Do you catch yourself analyzing how they made a particular shot, or do you get to enjoy the story itself?

Gonzalo: In a way, yes. When I’m in the middle of a project and I’m watching something, all I can see is how they did it – so I don’t really enjoy it. But if I’m able to disconnect, then I’m able to enjoy the story even more. If you don’t get pulled in, then you see the strings behind it and it’s not that enjoyable. But if it’s well done, if it’s powerful and it just sweeps you away, you admire it more than the average viewer. You know how much effort went into it.

I like watching movies, because I’m looking forward to see if it’s going to sweep me off my feet, or if I’ll end up thinking about how many days it took to shoot the scene.

Kirill: You mentioned “when you roll camera”, but that’s almost obsolete now that digital has taken over. If you look at these first 20 years of your career, how different is it today compared to when you started?

Gonzalo: It’s pretty different. When I started, there was just video assist. You could see what the camera was doing, but there was no way of telling how it would look until it got developed. There was a little bit of a magic element to what we did as cinematographers. Some people complain that it’s lost and that the magic is gone. But I don’t see it like that.

I see it as another way of communicating with someone. You communicate with the director, and you both see something that is quite close to what the final image is going to be. You can discuss if it should be darker or cooler or warmer. You’re still the cinematographer. You are telling the vision of the director and not only your own vision. The more tools you have to communicate, the better it is, especially on subjective things like color or brightness.

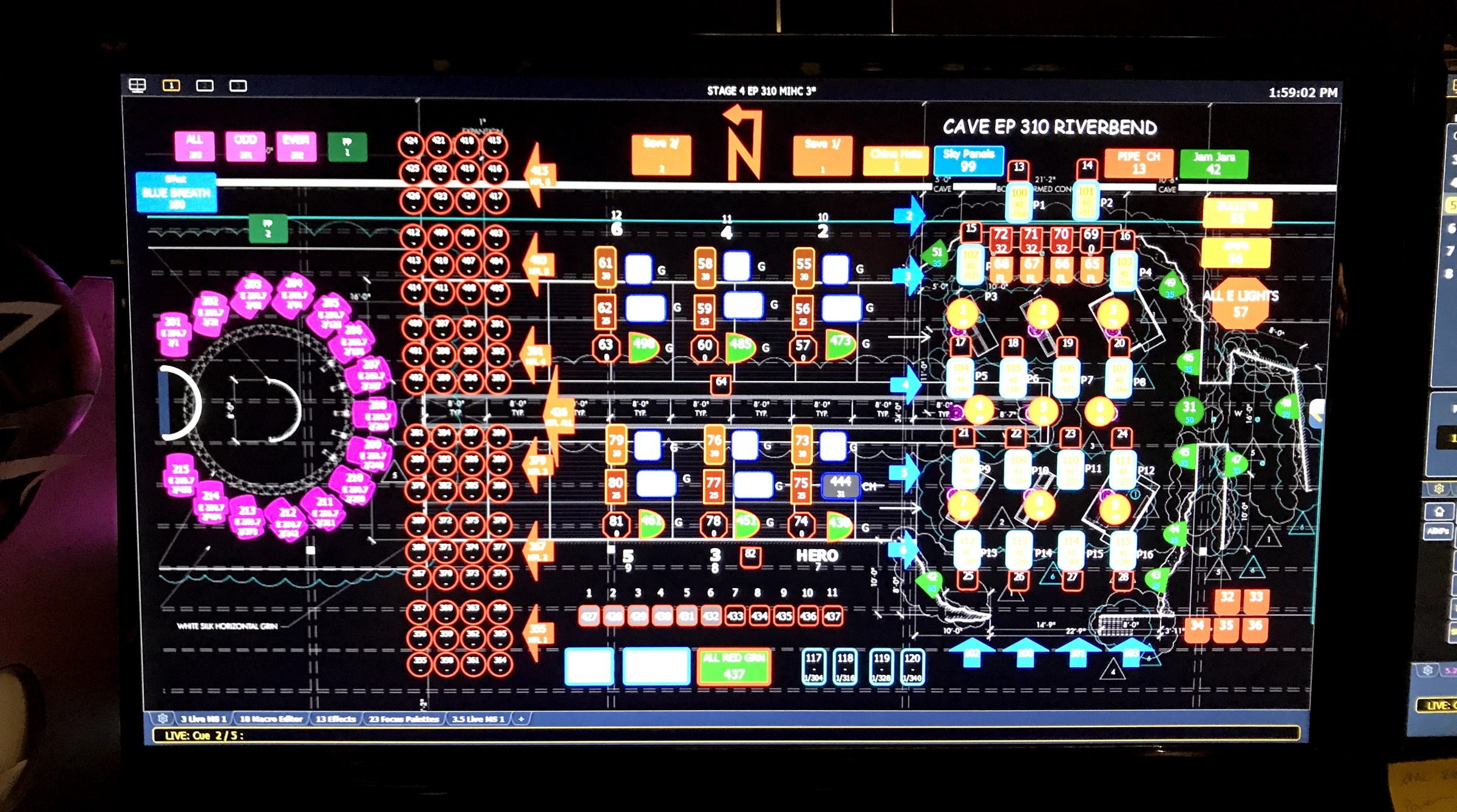

Technology has also changed the way we do color correction in post-production, and the way we work with lights on set. You can program lights and change light during a scene. It can be programmed to change color during the scene, and you have other nice storytelling tools like that. Nowadays we can be shooting an exterior scene, and program lights to simulate a cloud passing by. You make the backing light a bit darker for 30 seconds, and then bring the brightness back up. It’s subtle. It gives you a sense of realism, even if the viewer doesn’t notice it on its own.

Behind the scenes on the sets of “The Man in the High Castle”. Courtesy of Gonzalo Amat and Amazon Studios.

Kirill: Is it time-consuming to keep track of all these changes in technology?

Gonzalo: Quite so. When you’re shooting, you can’t dedicate the time to anything else. So every time I have a break, I have to brush up on what came out and stay up to date. You have new cameras, new lenses, new lights coming out all the time. It’s hard to keep up. But it’s also part of the job. I like to test new things every once in a while. It’s nice to use new technologies and not get too used to the old ones.

Kirill: Between the technical and the artistically parts of it, is one more important than the other?

Gonzalo: You have to have a good balance between the two, even if sometimes you end up paying more attention to one. When you read the script, you start with the artistic part to get ideas. Then you translate that to the technical side – what lights do we need, what cameras we are going to use, how do we shoot it. And then, when you’re on the set, you go back to the artistic part. It’s kind of a full circle, and you constantly have to go back and forth between the two.

My approach is to keep it more on the artistic side until I get to talk to the director. I take it from Conrad Hall who would discuss the idea with his crew, before executing it. If you know the crew, the technical part of it is known to them. They know what to do. So I prefer to keep it on the artistic side, even though the technical side is important for completing the production.

Behind the scenes on the sets of “The Man in the High Castle”. Courtesy of Gonzalo Amat and Amazon Studios.

Continue reading »

![]()

![]()

![]()