Continuing the ongoing series of interviews with creative artists working on various aspects of movie and episodic productions, it is my pleasure to welcome Jess Dunlap. In this interview, he talks about the transition of the industry from film to digital, finding the balance between technology and art, the meaning of art, and advice he gives to younger cinematographers. Between all these and more, Jess dives deep into his work on “Herman” that is releasing on video-on-demand channels tomorrow.

Kirill: Please tell us about yourself and the path that took you to where you are today.

Jess: I’m a cinematographer, currently based in Los Angeles, but I am originally from Massachusetts – not too far from Boston. I went to Emerson College to study film and specialize in cinematography. I didn’t know until late in my childhood that I wanted to do anything in film, or even anything artistic long term. I did have artistic passions like music, but I was a science and math oriented student. I excelled in math, biology and chemistry, and I thought that’s what I wanted to study.

Then I reached a point later on in high school, where the standard setup of academia felt frustrating. I felt a lot more drawn to my artistic side, and it was music that opened up my eyes to the fact that one can pursue something artistic. So in a lot of ways, I abandoned my math and science oriented self, and decided to pursue filmmaking, almost on a whim. I was not super obsessed with movies, and it was a total 180-turn in my life at that point. It really felt like I was abandoning that more technical side of my mind.

I went to film school thinking that I would be a writer and a director, and that it would be a purely creative artistic process. Then I started working on a couple of short films during my first freshman semester, and I saw the role of the cinematographer, and I saw that it was obviously a perfect marriage of the technical and the creative. I saw that I didn’t have to abandon that math and science oriented side of myself. I saw that I could still exercise those parts of my mind, but be creative at the same time. Typically it takes me a while to make major life decisions, but that one came pretty easy. I watched the DP shooting on my first or second short film at Emerson, and I knew that it was what I wanted to do.

From there, I kept on pursuing that path. And since then, it has maintained its complexity, and how it challenges my left brain and my right brain at the same time. I love it.

Jess Dunlap (right) on the sets of “Herman”.

Kirill: In this marriage of technical with artistic, do you find that one is more important, or is it a balance of the two?

Jess: It’s definitely a balance of the two. At times you do need to weigh one heavier than the other. You need the ability to go really technical when you need to, and the ability to go really artistic when you need to. If you’re not a highly technical person, it’s fine. There are ways to pick up the slack. Once you reach the level of cinematographer, you have camera assistants, you have a gaffer and a key grip who handle almost all of the technical issues for you. You don’t need to be an extreme technician.

Even within the artistic side, we’re exercising those capabilities of our mind that work with geometry, space, and physics. It is a role that’s well suited to someone who thinks in those ways.

Kirill: Do you feel that your field lost something important in the transition from film to digital?

Jess: Yes, at least from the perspective of a cinematographer. When I went to film school, we were shooting on film. Digital only started to really take hold at the end of my time there, so most of the bigger projects that I shot were on 35mm and 16mm.

When film was more dominant, the experience was that the cinematographer was the only one on set who knew how it was going to look. Maybe the camera assistant or the gaffer had an idea, but the cinematographer was really the only one who knew how it was going to look in the end. There was the monitor, but it was for framing. It wasn’t for lighting or exposure. Nobody knew what the mood was that was being created. The director described it and had their vision of it, but at the end, it was in the mind of the DP. Selfishly, it was fun. It was fun to be on set feeling like a kind of magician who has all these creative visual ideas running through you. Everybody else wanted to know how their work was going to show up – the costumes, the make-up, the production design.

Nowadays, a little of that is lost. You only need to look at the monitor to see what your work on costume, makeup or sets looks like. In some ways that’s good, because you can make more efficient decisions. But there’s something lost in the experience of the cinematographer.

There’s another difference in how much care went into shooting on film. It’s a more delicate process where mistakes matter more, and mistakes can be more expensive. The way we shoot on digital is you keep on doing more takes. You have time, and you keep on going, and you eventually get your take, but there’s something that is lost in there. There’s a little less pressure for everybody, including camera operators and even actors.

Continue reading »

Continuing the ongoing series of interviews on fantasy user interfaces, it’s my pleasure to welcome Dave Henri and Stefan Grimm. Dave founded Modern Motion Pictures back in 2009 to provide services to design and present screen graphics for film and TV. Some of the company’s more recent work includes “First Man”, “For All Mankind” and “The Morning Show”. Stefan first joined the industry to work on “Powerless”, and later on “Constellation” after he joined Modern Motion as a partner. In this interview Dave and Stefan talk about their work on the just released “Alien: Earth”, going back to the original aesthetic of the first “Alien” movie and expanding it to the bigger storytelling universe of the show.

Left – Stefan Grimm, right – Dave Henri.

Kirill: Please tell us about yourself and the path that took you to where you are today.

Dave: I’m Dave Henri, and I founded the company Modern Motion Pictures in Los Angeles in 2009. At the time it was a one-man operation to create screen graphics for use on set. I was an on-set operator and an engineer for a few years, and during that time I’d done an occasional graphic here and there, and I realized I needed a way to bill for it. The company took off, and I started doing a lot of my own shows – doing design and technical on-set work together. A few years into it we brought on our first partner Chris Cundey, and a few years after that the third partner Matt Brucell. By that time we’d been working quite a bit with Stefan. The first show we worked on together with him was “Powerless” set in the DC cinematic universe. A few years ago right after Covid we set up a German LLC / GmbH to handle European productions, and we brought Stefan on as a partner.

That’s the brief history of it, and as for why we do it – it’s just so much fun. You start with a blank screen, and a few hours later you have a moving graphic that’s going to be photographed and used on set – it’s amazing.

Stefan: I started in early 2000s as a web designer. Over time it kept on getting bigger, and grew from a one-man show to a small agency. When the first “Iron Man” came out in 2008, I looked at the Tony Stark’s helmet interfaces and started thinking about how those can be achieved. I was using mostly Flash in the beginning, but it was already starting to phase out at the time and I switched to After Effects.

As I continued doing web design, I also felt like I needed to play around with FUI [fictional user interfaces]. At that point I wasn’t aware that there was a term for it, and it was hard to search for references online. I was experimenting with trying to achieve the holographic looks inspired by Tony Stark’s helmet. A bit later in 2016 I made a small animation that counted from 0 to 100, and uploaded it on Behance. That’s when Dave appeared in my inbox and asked me if I’d be interested in doing graphics for TV shows.

It felt unreal. I come from a small city in Germany, and I considered myself to be lucky to be doing web design. I never had any thoughts about working in the movie industry. We had our first phone conversation, and I was really excited. But my first reaction was to refuse it, because I didn’t know anything about this industry. I did ask Dave to send over some examples he had in mind for “Powerless”, and I gave myself a weekend to revise those designs to be more aligned with my design approach. When it was done, I sent him a huge email, detailing all the changes and why I made them, and that’s how I ended up on that show. Those were my first baby steps into this industry, and I’m still enjoying being a part of it.

Screen graphics for “Powerless”, courtesy of Modern Motion.

Kirill: There are so many screens in our lives today, and they do find their way into the movies and TV shows. There’s not a lot of screen estate on phones, but they are so deeply integrated into everything we do every day. Do you have a preference on the size of the screen you enjoy designing for?

Dave: As a company of designers and programmers, we’re building a lot for phones for the moment. We developed a proprietary software called Magic Phone that perfectly emulates either an iPhone or an Android, and it’s quickly becoming an industry standard. We use it for all of our shows, and also license it out to other developers and designers. It does everything from phone calls to texting to social media browsing and more.

Like you’re saying, phones are everywhere. It’s become an increasingly important part of telling a story in modern day. You just can’t ignore phones. Characters are texting each other, whether it’s a romance or a spy thriller. We also do shows with big screens in big rooms. “For All Mankind” has had multiple mission control sets throughout its five seasons. “The Morning Show” has the studio set, as well as the control room. We also did Mission Control on “First Man”.

I personally like the bigger, more out there stuff. It’s a little more exciting to be working on. But it’s also nice to be able to bring the reality of a phone call or a text, to fulfill something that is critical to a story and to make it look accurate. It’s getting a lot better, not just with our software but with other people’s work. A few years ago, if a character got a text from his wife, it was the only text in the thread. We did a big push with productions to give us the previous texts in their history. We might not see them text back and forth, but there has to be something there on the screen. It’s an interesting part to be striving for that realism.

Stefan: For me it’s definitely the big screens. My favorite sets are the ones where big screens and small screens are stitched together in a rig so you can play around with different sizes of graphics. I love mission control sets, and I’ve done a lot of those in the last two years [laughs]. Phone graphics are more tied to reality, because people use their smartphones every day. They know how it should look and how it responds to your inputs. – while a mission control set can be something more of a fiction. That’s why I have a bit more freedom to play around.

Screen graphics for “Powerless”, courtesy of Modern Motion.

Continue reading »

Continuing the ongoing series of interviews with creative artists working on various aspects of movie and episodic productions, it is my pleasure to welcome Stefano Baisi. In this interview, he talks about transitioning from interior design to designing film productions, what art is, building the worlds that support the story, and his thoughts on generative AI. Between all these and more, Stefano dives deep into his work on the just-released “After the Hunt”.

Kirill: Please tell us about yourself and the path that took you to where you are today.

Stefano: I graduated in architecture years ago and I started working in the interior design field here in Milano. Over the years I experienced different styles of projects, including working on fashion shows as a PA early on. After a while doing residential and retail projects, I met Luca Guadagnino. A friend of mine – a photographer and architect that used to study and work with me – met Luca on a photography assignment by a magazine. That was at the same time when Luca had his first commission as an architect and as an interior designer. They started designing a villa together on Lake Como, and after a while, they needed help. That’s how I met Luca back in 2017.

It started from that one project of a director that decided to do a design project, and grew over the next five years into a full interior design studio. During that time, I think I expressed my attitude in designing, and in 2022 Luca asked me to design “Queer”.

Kirill: How was your transition from the world of interior design into doing production design for film?

Stefano: When you design for the movie, you must be coherent to the movie and adhere to the story – instead of designing something because it’s beautiful. The environment is an extension of the characters. That’s how I approach it.

Design illustration for “After the Hunt” by Stefano Baisi, courtesy of Amazon MGM Studios.

Kirill: How do you see the role of a production designer? What do you think is not well understood about it by the outside world?

Stefano: From my own perspective, I can see the work of other people and understand the depth of the work that exists behind the production. For production design specifically, I would say that people don’t understand how much work goes into it, and how little time we have to do it.

We started prepping “After the Hunt” in May 2024, and the movie wrapped in mid-August of that year. That’s not a lot of time. When you design a space like Frederik and Alma’s apartment, the audience might not see the level of detail and thinking that went into every choice – from the colors on the walls to every single piece of art and every book on the shelves. There are thousands of books in Frederik’s study, and choosing each one gave his character more depth. You can’t always see how deep it goes, because most of the time it’s in the background, and maybe blurry and out of focus. There’s a lot of research and work behind a production like this one.

Design illustration for “After the Hunt” by Stefano Baisi, courtesy of Amazon MGM Studios.

Continue reading »

Continuing the ongoing series of interviews with creative artists working on various aspects of movie and TV productions, it is my honor to welcome Rick Carter. His wonderful career has brought us the worlds of the original “Jurassic Park” and its “The Lost World: Jurassic Park” sequel, “Forrest Gump”, “Cast Away”, “Polar Express”, both sequels in the “Back to the Future” trilogy, “Star Wars: The Force Awakens” and “Star Wars: The Rise Of Skywalker”, “Munich”, “Lincoln”, “A.I. Artificial Intelligence” and “Avatar”. He has won Academy Awards for the production design of “Avatar” and “Lincoln”. In this interview Rick talks about building a world that serves the story, the expansion and evolution of the role of the production designer in the last 50 years, the magic of watching these stories on big screens, and what advice he’d give to his younger self.

This interview is the third and final part of a special initiative – a collaboration with the Production Designers Collective that was founded in 2014. This collective brings together over 1,500 members from all around the world, sharing ideas, experiences and advice across the industry. We talk about its goals and initiatives, and the upcoming second International Production Design Week scheduled in mid-October this year. Here you can browse its full program, where you can filter by country, city, category and more to find an event near you.

Kirill: Please tell us about yourself, and how did you start in the industry.

Rick: I grew up around the Hollywood filmmaking industry because my father was a publicist. I knew about it a little bit from the inside, but I wasn’t sure I wanted too much to do with it. After I went traveling extensively as a young man, it seemed to fit because of the art that was embedded in the art direction. It felt like that it would be a good path for me to see if I can make my way.

I think I came in also to a fortuitous time because the industry was in the midst of a lot of changes. This was in the early 1970s, and I was able to meet some people that I got along well with. So I had it quite good, because once I met Steven Spielberg and Robert Zemeckis, I had 20 years of the two of them as these two brothers, almost an older brother and a younger brother that I could collaborate with. They were so good at what they were doing in terms of making movies, and they took me along for the ride. I attribute a lot to where they went with their ideas and how those were realized.

It felt like I was growing up going on those adventures through the movies that we did together, from “Back to the Future” to “Jurassic Park” to “A.I. Artificial Intelligence”. There were so many adventures to go on in the stories – time travel, dinosaurs slave ships and islands, the future with the AI. I was introduced to so many worlds, and then I was the one who got to be in charge of making the worlds. That was an adventure to be called upon from my early thirties to my mid fifties. They were jobs, but it wasn’t that formal. It felt more like I was being invited to partake of their fantasies. And they were very interesting people, and they were successful with what they were doing.

Kirill: Would you say that you got to participate in this transition from special effects to visual effects? What kind of world building it unlocked for you?

Kirill: Would you say that you got to participate in this transition from special effects to visual effects? What kind of world building it unlocked for you?

Rick: There was the digital revolution, moving from analog to digital, and from optical to digital. The expansiveness of the digital realm has opened up how big the worlds can be as they come across on screen. They’re not necessarily built out more physically, and so the production design is more split now between the physical and the digital side of it.

It can be an historical world or a fantasy world, but they all share the same DNA for me. I ask myself how could I believe this? How could I truly be inspired to be at that place? That’s what I try to bring to the production design – the authenticity of the place that I’m in. I want to have it feel like it serves the story in the right way. And also, it needs to come together emotionally to be supportive of the actors and the narrative of the story. It’s an intuitive process, and there are many levels to manage through the process, be it set decoration, illustration or digital arts.

As production designers, we’re in the midst of this expansive arena, and it keeps on expanding as the technology keeps on expanding. Generative AI is just the latest example of this.

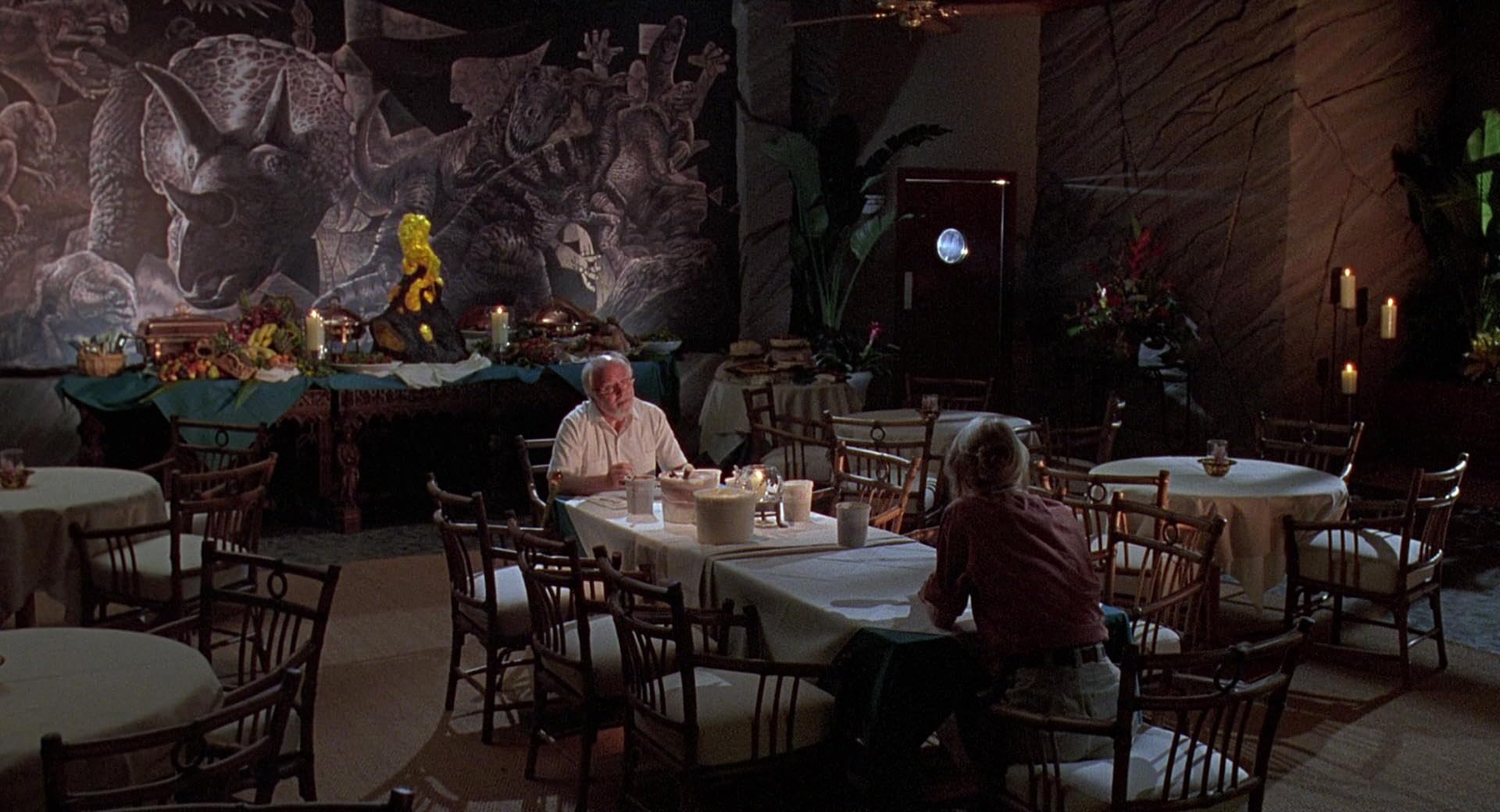

Rick Carter’s work on “Jurassic Park”.

Kirill: How do you see the role of the production designer evolving over these last few decades? I’m partial to the ’50s and the ’60s, with Hitchcock and Kubrick as some of my favorites. I just rewatched “Breakfast at Tiffany’s” and “To Catch a Thief”, and there is no production design credit. It was art direction, which later morphed into world building, and separating – or maybe elevating – the role of the production designer.

Rick: The elevation creation of the production design credit happened all the way back in 1939 with “Gone with the Wind”. They gave William Cameron Menzies a special title called production designer for that production, because he had so much involvement in all the development of the whole movie getting made.

But at that point, most people that were in the art direction end of it – they were art directors. Then, as you said, production design started slowly getting credibility through the ’60s into the ’70s. That gets to the era that I’ve been involved in, starting in the ’70s and all the way until now, where the movies have become so complex that more often than not, I’ve had co/production design collaborators. The role is so big and so diverse, and it’s important to have a way of making it cohesive, which often is beyond the capacity of one person. And it’s never really one person anyway. It is so collaborative. There’s so many people involved.

It certainly has expanded during my time. It used to be about drawing up physical sets and maybe do some illustrations, but nowadays it is about world building. We’ve also seen many games taking advantage of world building. You might or might not have a narrative in a particular game, but the world is still in there.

I don’t know where it’s going from here. It’s extremely expansive because of how much even my own minimal experience with the AI has been. I look at the AI as a partner and not a tool. It’s an advancement of what started with the digital revolution, and now it’s going that much further. You mentioned Kubrick, and he is in many ways a godfather of the concept of the AI. It wasn’t specifically digital in “2001: A Space Odyssey”, HAL is the entity brain. And then I got to work on “A.I. Artificial Intelligence” which was Kubrick’s concept.

I am old enough to have been around at those times, and that was my learning curve to see it a little broader than most people see it now – in the evolution of it from the analog times in the beginning of production design, through going into the digital realm to design worlds. Calling it “worlds” is an interesting way for people on the outside to perceive it. It’s almost a magician’s act. You’re always involved in something that the audience can see. But you have to really look at it and admire it. And when you’re admiring production design, you’re not into the movie. It’s almost going antithetical to how most people like to watch movies.

Rick Carter’s work on “Jurassic Park”.

Continue reading »

![]()