Continuing the ongoing series of interviews with creative artists working on various aspects of movie and TV productions, it is my absolute delight to welcome Natasha Braier. In this interview we talk about the art and craft of cinematography, the hierarchical structure of feature film productions and how that structure still lends itself to predominantly male voices, and the pleasure and pain of working long hours over months at a time. The second half of the interview is on Natasha’s work on the meticulously crafted “The Neon Demon”, an engrossing story of a young girl taking her first steps as a fashion model in the wild urban jungle of Los Angeles.

Natasha Braier on the set of “The Neon Demon”. Courtesy of Natasha Braier.

Kirill: Please tell us about yourself and how you started in the field.

Natasha: I was doing still photography when I was a teenager. It was mostly black-and-white, developing them in my own dark room. The first time I looked at the end credits of a movie and saw the title of director of photography was when I was nineteen. I was immediately interested in that, and some of my older friends who I studied photography with had chosen to go to film school. It was through them that I discovered that world and the role of a cinematographer. That’s when I decided to go to film school myself.

Kirill: Do you remember being surprised at anything in particular when you started there, when you saw how things worked behind the camera?

Natasha: I wouldn’t say that I had big surprises. There were a lot of things to learn that were different from the world of still photography. If there’s anything that I didn’t know at the time I made the decision to go to the school and go down this career path, I’d say that I didn’t know that it would be such an intense commitment. You barely have time to have a life, and I didn’t know that I was going to spend so much time traveling and working away from home.

Also, I didn’t know that you could make so much money as a cinematographer. That was a nice surprise. I thought that I was going to be a humble artist doing what I love, much like other artists that I saw in my life. It was a good surprise that I get to travel the world and see all the exotic places, and make money. And the other surprise was that if you want to be home for a few months, that’s difficult.

Kirill: Looking back to when you were in school, what happened to people that went to that school with you? Are most of them still in the field, or do some leave it as years pass by?

Natasha: I went to a couple of film schools because I was moving with my family. I only stayed a few months in Argentina and another few months in Spain, and then I spent three years getting a master’s degree in cinematography in England. That’s the only education that I completed end to end.

That program was very selective, accepting only six people every year for each field. The other five that started studying cinematography with me that year were older than me, in their late twenties and thirties. Some had been camera assistants before, and they were really committed to this work. It was difficult to get into that school, and once you got in, you continued afterwards in the industry. Some had more success than others, but all of them are still working in the field.

Kirill: As you said, your job is quite intense, and you spend long months away from your family and friends, and long hours on set once the shooting starts. If we’re talking about you, what makes you stay in your field?

Natasha: It’s a great job and I love doing it. It comes with a cost, and otherwise it would have been a paradise. You pay a price. You have your freedom – you don’t go to the same job every day, you don’t have a boss, you get to choose your projects, you get to travel and meet different people. And the price you’re paying for that freedom and flexibility is that you don’t always know what you’re doing next month.

I think the world is divided into people that can live with that and people who need a stable life and a stable job. If you’re not the former, you will probably not stay in film industry. If you talk about people in the industry, we are not very normal [laughs]. We need the adrenaline and the highs. It’s like being on a rollercoaster. You have your ups and downs. That’s the challenging part of the work.

Over the years I’ve learned to deal with that in better ways, to not get so anxious about what I was going to do next, and to trust that there’s always something coming. I started enjoying the moments when I’m working a lot more, and to stop worrying about what’s next. It’s also a big spiritual test where you need to learn a lot about patience and not having control over what’s next.

Continue reading »

It’s no secret that the world of episodic television is going through a period of tremendous creativity. Continuing the ongoing series of interviews with creative artists working to bring a fantastic variety of story telling to the screens in our lives, it is my delight to welcome Crescenzo Notarile, ASC. His career spans close to three decades, and in the last few years he has worked as a cinematographer on “Ghost Whisperer”, “CSI” and, most recently, the second season of “Gotham” – for which he is nominated in the category of outstanding cinematography for a single-camera series.

In this wide-ranging interview Crescenzo talks about the changing field of cinematography, the rising bar of story telling on screens big and small, the crazy pace of working on half the episodes in a 22-episode season, collaborating with different directors over the course of that season while maintaining a consistent visual language throughout the arc of the show, what happens when the show heads into the post-production and his collaboration with his colorist and the VFX department, and how easy (or hard) it is to find a simple answer when people outside of the film industry ask him what it is exactly that a cinematographer does for a living.

Kirill: Please tell us about yourself and what drew you into the industry.

Kirill: Please tell us about yourself and what drew you into the industry.

Crescenzo: My father was in the field of advertising, working as an art director, graphic designer, and illustrator… He was in very high demand at the time – a quintessential ‘Madison Avenue Mad Man’. One of his photographers at that time was Richard Avedon, and when I was a young boy, 4-9 years of age, I had the privilege and the opportunity to watch Richard work with my father, even though I was not aware of his fame at the time of course.

Both my parents were artists, (my mom was an interior designer, sculptress, and painter), and we had hundreds of art books all around the house. I too wanted to become an artist, a photographer, and it all started when I was watching my father work. I was conscious of this at that time, and knew I had wanted to be a photographer ever since I was 5 years old… Soon thereafter, my father brought home my first 2 cameras; a Brownie, and a Polaroid – all for me! They are now trophied in a glass case in my office.

Kirill: How much has your field changed since you joined it professionally?

Crescenzo: They say that it takes a lifetime to become a cinematographer – and it certainly does! Every day is a learning process, perpetually shifting. It might be a new view point of aesthetics, new stimulation, new technology, new equipment, or a new philosophy in the way I think about my work and how I should approach it at my current state of mind. It might be the barometer of our pace of our society, our culture, and how we story tell our lives at this time of life. It changes day to day to day. You never stop learning in the art of what we do – because art is life!

From the beginning to now, it’s still a growing process. In fact, the more you learn, the more you realize you have more to learn. That’s the paradox of it all. You filter all that information and knowledge inside your heart, mind and soul, and you try to collectively use that to fuel your sensibility to express your stories. When you become sharply in tune with this personal ever changing growth, you now realize, your learning starts all over again because it’s a different plateau of thinking – thus, a different aesthetic and different approach to your personal execution…

This day and age we have new technologies and new equipment. Sometimes you need to be a computer engineer to shoot something these days. It’s constant learning. To be honest, it’s not gotten any easier. That’s for sure. It just becomes more arduous and more challenging as we progress as a culture, as a society and in the field itself. There’s just so much information out there, so many choices, so many options, so many opinions, so many approaches, so many menus, and an infinite amount of stories to tell…

Kirill: Is it due to growing expectations from the production values, or perhaps the technology is getting more complicated?

Crescenzo: I think, mainly because of the so-called, “bar”… The intellectual bar, the creative bar, the bar of the audience wanting more – that’s what makes it more challenging and difficult with each passing year. The bar itself keeps rising and rising. There’s so much brilliant content out there right now. There are so many wonderful shows, and it becomes more challenging not only to surface yourself above the few that are around you to be nominated, but also to just watch the content itself.

You can only watch so much. There’s only so much time in the day, and one’s personal time in their day. That becomes challenging as to what shows you want to electively choose to watch, and why do you want to watch those shows. It is challenging for the networks, the studios and the executives. The bar keeps rising, not just at the creative level, but also at the physical content level.

Courtesy of FOX’s “Gotham”.

Continue reading »

Continuing the ongoing series of interviews with creative artists working on various aspects of movie and TV productions, it is my pleasure to welcome David Crank. In recent years David worked as art director and production designer on productions such as “The Master”, “Inherent Vice”, “The New World”, “There Will Be Blood”, “John Adams”, “Water for Elephants”, “The Tree of Life”, “To the Wonder”, “Lincoln” and his most recent “Concussion”. In this interview he talks about the art and craft of production design and how it evolved over the last couple of decades. The second part of the interview is about David’s work on the remarkably crafted sets of “The Double” – a dark satirical comedy whose visuals grip you from the very first frame and don’t let go long after the movie has ended.

Kirill: Please tell us about yourself and your path so far.

David: I worked for about ten years designing sets and costumes in theater, and then switched over to film around 1990. Film was what I always wanted to do, but I didn’t have that opportunity in Richmond where I grew up. I enjoy both disciplines, but I like being able to concentrate on one project intensely and then go on to the next one, whereas in theater you needed to have two or three going on at the same time in order to make a living.

Kirill: If you consider storytelling in these two mediums, theater and film, are there any big differences, or is it sufficiently similar?

Kirill: If you consider storytelling in these two mediums, theater and film, are there any big differences, or is it sufficiently similar?

David: There are different techniques you use, but to me, the storytelling aspect of it is fairly similar. If it happens to be on stage, you can do it one way, and if it’s on film, you can do it in another way. But your ultimate goal is still telling an interesting story in an exciting fashion, and hopefully, engage people. In terms of design, there are small technical differences, but really, design is design. You still apply the same knowledge and skills to both mediums.

Kirill: To me it feels like you have the fixed space on stage, and you can’t take the viewers closer or farther away in the same way that a film camera can.

David: True, you still do the same things. In film you do close-ups and shift the focus with the camera, but in theatre, you can also control the focus on stage by directing the eyes of the audience through design and lighting. It’s a different scale and done in a different way, but, in effect, you’re still doing the same thing.

Kirill: Do you find that some stories lend themselves to be better told on stage vs film, or does it depend on the talent of the storytellers to take advantage of the stronger sides of the specific medium?

David: There probably are some that do lend themselves to being better told on stage. I think, however, it’s similar to the question of what is better – a book or a movie? In a sense, you should be telling the same story, but taking a different path to get there. The method of each will be slightly different, and while you get certain things from a book that you wouldn’t get from a film, you also get certain things from a film that you wouldn’t get from a book. For me, with film, the main thing that you have to always be aware of is using a cinematic language vs. a stage language. How can you tell something in a movie in a way that you can’t tell it in a play? That’s what you focus on. That’s how you tell your story.

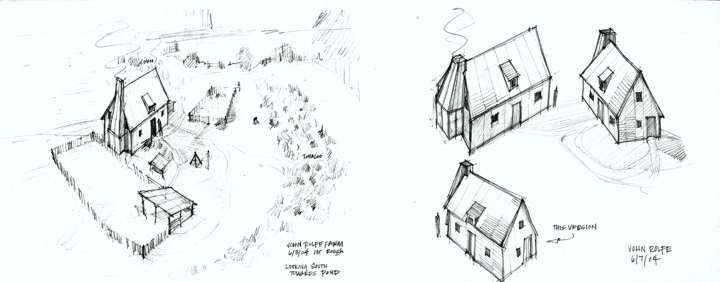

Layout sketches for John Rolfe farmhouse set on “The New World”. Courtesy of David Crank.

On the sets of “The New World”. Courtesy of David Crank.

Kirill: As you said, you started working on films in the early ’90s. That was before digital tools were as powerful and prevalent as they are today.

David: I started my career working mostly on historical dramas, because that’s what came to film in Virginia. Initially there was very little CGI used on projects that I was on, except to change the occasional background. The sets were built fairly complete.

Kirill: But even on historical dramas it gets pretty expensive to build very big sets.

David: Yes it can! When we did with “John Adams”, we had a massive number of sets to construct, many that were too large to build completely. We designed what we wanted them to be, and then sat down with VFX people and talked about what made sense to build in reality and what made sense to build digitally. You split up the work that way. It would be lovely to build it all, but nobody has the money for that [laughs]. You just attack each set separately and see what makes sense.

Sometimes you might build a bit more, because if you can do whole scenes without having to augment them with CGI, it might ultimately be cheaper for you. But, you might have a single shot that wants to pull back from there and show more building above, or more buildings beyond, and, that’s when it makes sense to add CGI. It’s different in every single case. There is no formula. You look at the specific problem, and you discuss how to best solve it.

Big top circus tent set on “Water for Elephants”. Courtesy of David Crank.

Continue reading »

Continuing the ongoing series of interviews with creative artists working on various aspects of movie and TV productions, it is my pleasure to welcome Mikhail Krichman. In this interview we talk about the start of his career in the early ’90s that coincided with the big political changes in Russia, his ongoing collaboration with Andrey Zvyagintsev that included the Oscar-nominated “Leviathan”, how stories cross cultural borders and how stories can change dramatically when they are told in a different language (dubbing or voiceover), and the transition of the industry from film to digital in the last decade. The second half of the interview is about Mikhail’s work on the wonderfully crafted world of the recently released “Miss Julie”.

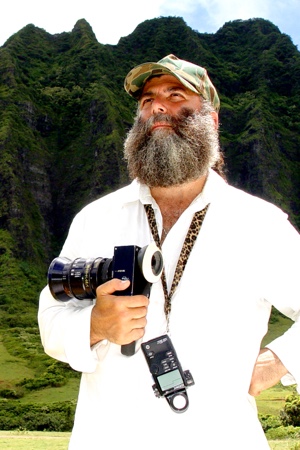

Mikhail Krichman on set. Photography by Anna Matveeva.

Kirill: Please tell us about yourself and how you got into the industry.

Mikhail: It happened almost accidentally. My parents come from the field of book typesetting. After finishing my army service I didn’t know what to do with myself, and I chose the easiest path. I wouldn’t say that it interested me that much, but I didn’t know anything else. I spent a lot of time in printing houses, and I liked the smell of the paint. Those were the things from my childhood that made me start my studies at what is now Moscow State University of Printing Arts.

It was around 1991. They had an arts department, but since I didn’t have any drawing skills, I didn’t have any thoughts about doing graphic design. I joined the department of technical studies, learning about the technology and the process of book printing. After third semester I moved to an extramural study program and started doing part time jobs. Those didn’t have any connection neither to what I do now nor to what I was continuing to study, and from what I remember from those activities, I might have even lost money doing them.

Mikhail Krichman on set.

Mikhail Krichman on set.

Photography by Anna Matveeva.And it so happened that I met a guy that was about to graduate from the cinematography department of the Gerasimov Institute of Cinematography. It was a birthday party, and I asked a question that probably a lot of people ask in a similar situation – would it be possible to visit a set and see how things work when they shoot a movie. We talked for a bit and then he disappeared, and I almost forgot about him. Then after a year he got in touch, saying that he had an opportunity for me to come and visit a set. That was how I saw a film set for the first time – as he was directing and shooting some kind of a commercial.

But that’s not how I started my path to becoming cinematographer. A bit later, again with the help of the same guy, I visited the editing room of a TV station. Back in the 1990s it was simply possible to go there and enter the buildings. The editing room was empty apart from one day a week. It was full with Betacams and mixing consoles, and I remember myself spending day after day reading the manuals, learning how different machines worked, trying to mix source materials that didn’t even belong to me. And after some time I became a junior editor.

Kirill: Without having some kind of a formal education in the field.

Mikhail: I noticed the people who knew what they were doing in the editing room, and started learning from them. It wasn’t overly difficult, and my boss saw that I wasn’t all that bad, so he kept me around. After a while I had a chance to sit through a number of study groups led by a teacher from the Gerasimov Institute of Cinematography. She was teaching courses on editing, and my boss invited her a few times a week to give lectures to me and my colleagues. She talked mostly about editing film, and it was a free-form dialogue. We didn’t have any strict plan, and keeping notes was optional even though we all kept detailed notes. She was a great teacher, and I learned a lot from her, things that stay with me until now.

I’ve spent around three-four years there, and then found the next step in my career. I met Leonid Kruglov who was doing a travel show for a national TV station. He invited me to Cuba to make a documentary with him, which was my first job in doing documentaries. It was only him and me, making a show about Santería and their religious beliefs.

Right around that time we had first appearances of small hand-held digital cameras from Sony. Betacams were already around, of course, but they were bulky and expensive, confining them to studio environments. The small digital camera that we had cost around $3,000 and we also got a wide lens, starting to experiment with this new hardware and what it allowed you to do in the field. It was amazing at the time.

I also started doing music clips, as directors liked that I was both shooting and editing the material. And I kept on doing that travel show, going with a slightly bigger crew of five and two cameras. We did Papua New Guinea, Brazil, Colombia and Peru among the rest. That was already 1999.

And then in 2000 I met Andrey Zvyagintsev that worked at REN TV at the time. He got offered to do “The Black Room” show, choosing a few short stories to shoot. He was looking for cinematographers to shoot individual episodes, and one of my director friends put us in touch.

Kirill: And you continued working with him afterwards.

Mikhail: Yes. We did those three short stories, each one 25 minutes long and not related to the others. The show was received well, and I was contacted by a film studio to do my first full feature, “Binge Theory”. Then I did “Sky. Plane. Girl” in 2002.

Kirill: I remember the years after the collapse of Soviet Union, where a lot of industries underwent very big changes, as what was controlled by the state and the party was now transitioning into private hands. What was the state of the film industry in Russia around 2000?

Mikhail: The industry lost a lot of talented people, key people across all departments, including second unit directors, camera operators and script writers. People lost their jobs during that period, going to other fields that didn’t even have much connection to arts. Some went abroad and some just disappeared.

I wasn’t a big fan of Russian cinema at the time. I remember seeing differences in the artistic and visual quality of American, British and French films. I was also younger, and American movies were much closer to my taste as well. I can’t remember a single local film from the ’90s that had left a powerful impression on me. There were a few indie films that failed to deliver on their promise, and a lot of them went nowhere. Also, due to lack of budget, most of them were not done that well compared to european or American productions.

I think that aesthetics are an important part of making a film. When the form is untidy and messy, the content is sometimes lost. And that was struggling to pull their weight against the smooth form of the American films. It feels that only now I am starting to discover Russian cinema. Andrei Tarkovsky was a formidable figure. I might not have been able to appreciate his content at the time, but the form was powerful.

Continue reading »

![]()

![]()

![]()