Continuing the ongoing series of interviews with creative artists working on various aspects of movie and TV productions, it is my pleasure to welcome Richard Bloom. In this interview he talks about his path through the various positions in the art department in his career so far, the changes in the world of episodic productions in the last few years, differences between feature films and episodic television, and what stays with him after a production is over . Around these topics and more, Richard dives deep into creating the worlds of the beautifully crafted “Briarpatch”.

Richard Bloom scouting the dunes for Episode 9 of “Briarpatch” with location manager Dennis Muscari behind left shoulder.

Kirill: Please tell us about yourself and the path that took you to where you are today.

Richard: I was born and raised in Memphis, Tennessee. I discovered my love for theatre in high school, and then went to college in Virginia where I double majored in theater and business.

I knew I loved theatre and design. But right after I graduated from college, I got an opportunity to intern on a film in Los Angeles. So I got in my car and drove from Williamsburg to Hollywood. Then the next day I showed up at the production office of “Austin Powers: The Spy Who Shagged Me”.

Within a couple of weeks that internship turned into my first PA job. And at the end of physical production I had come to meet Mike Myers, and he asked me to be his post-production assistant. So what I thought was going to just be a summer in LA turned into a much longer stay. I ended up working for Mike for a few years as a writer’s assistant. I learned a ton. It was a master class in Hollywood.

Ultimately, I knew that I didn’t want to be an assistant. I wanted to get back into design, so once I left that job, I picked up the crew list from “Austin Powers” and called the art director. As luck would have it, he said that he was going to start a project that week. I showed up, not really knowing what I was getting into.

That project was a small movie called “Donnie Darko.” And Alec Hammond, the designer, asked me if I wanted to be the art department coordinator. I jumped at that offer and then that project went union. It was pretty lucky. I owe a lot to Alec.

Soon after, I met Bo Welch and worked as his art coordinator for many years on many projects. Then slowly I became an assistant art director (thanks to Bo and Maya Shimoguchi), then an art director, and then many years later a designer. I’ve had design opportunities over the years, but “Briarpatch” was the first project that really felt right. It’s also the first series for the showrunner, Andy Greenwald. He’s a fantastic writer and a fantastic guy. I was excited about collaborating with him, and so I said “yes”.

Production design of “Briarpatch” by Richard Bloom.

Kirill: If I take you back 20 years ago, and then from that time jump straight to “Briarpatch”, would you say that the changes the art department has undergone through this time have been gradual or drastic?

Richard: I think it’s been fairly gradual over the years, but for the particular jump from “Men in Black 2” to “Briarpatch” it would be pretty drastic. If making a blockbuster is like running a marathon, making a TV show is like running a marathon of sprints. You have new scripts coming in all the time and a new director showing up every week. You are opening 3 sets a day and prepping 3 more and scouting the next episode. It’s a non-stop cycle. It’s pretty intense.

On “Briarpatch” we were shooting each episode in 8 days, which is quite lean in terms of shooting days. But the appetite is of course to compete with the shows that have bigger budgets and more resources. We had a small crew running at full steam for the episodes. But luckily, the crew was top notch.

I was really blessed to able to bring an art director from LA, Callie Andreadis. She is amazing, and we really have the same shorthand. Our propmaster Jonathan Buchanan also came from LA, and he was fantastic. He was off and running on his own. And then, of course, we had a really strong team in New Mexico lead by our set decorator, Kevin Pierce, and location manager, Dennis Muscari, and our construction coordinator, Robert Fritz. We all had to be on the same page early on, because once we started going, there was really no stopping. And luckily, all the departments worked really well together.

Sketches, plans and set photos of “Briarpatch”, courtesy of Richard Bloom.

Kirill: Did it help for the continuity of the show that you were the art director on the pilot, and then some months later you started doing the whole series?

Richard: Definitely. We had shot the pilot earlier, in the fall of 2018. Brandon Tonner-Connolly designed it and I art directed it. It was a really good taste of what was to come and I got a feel for all that Albuquerque has to offer. The writers’ room hadn’t started when the pilot was shot, and although Andy had a lot of ideas where the show was going there was still a lot to be imagined.

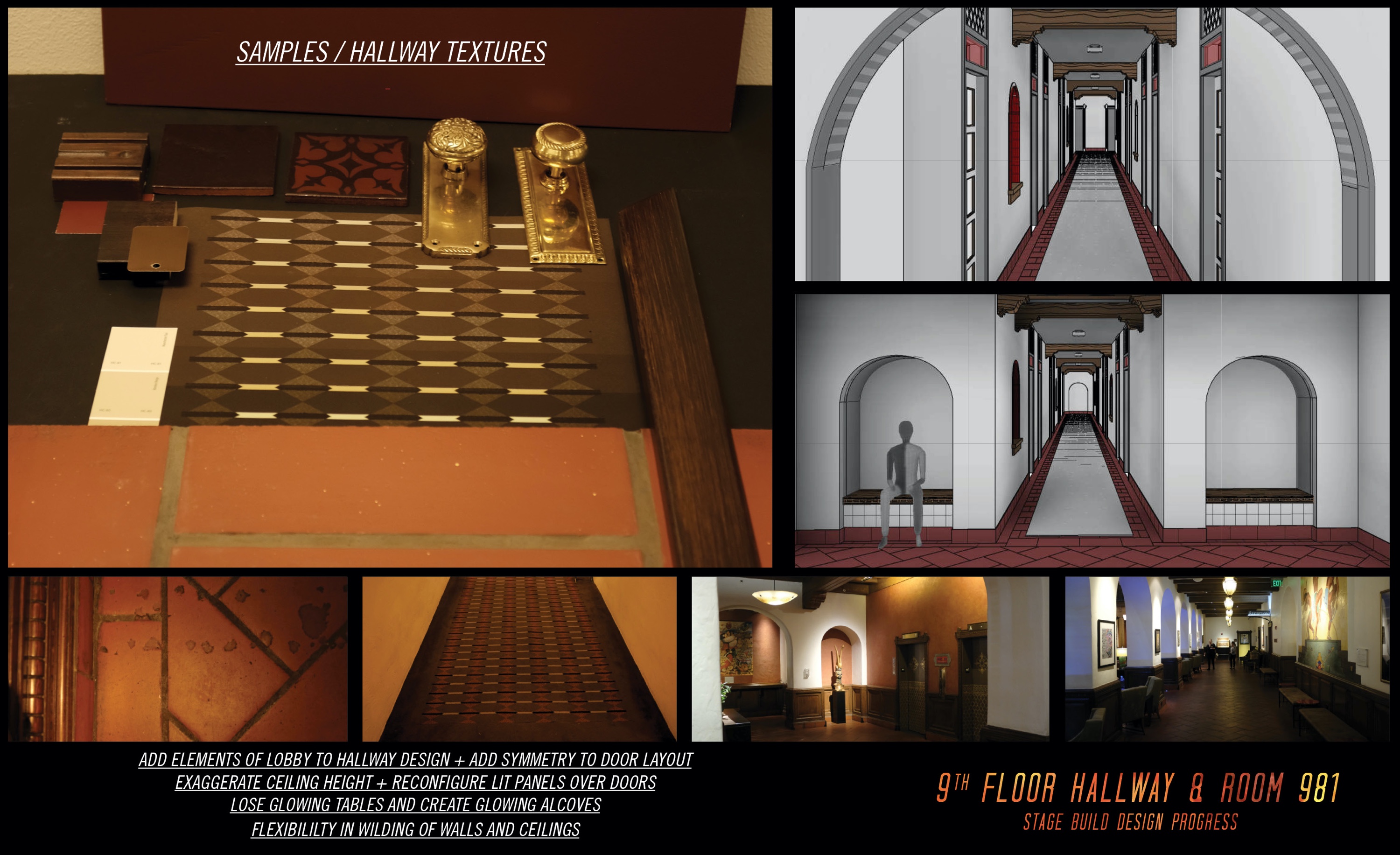

We didn’t build any sets on the pilot. It was all location based. So one thing that I knew coming back for the series is that we were going to build the hotel hallway and the hotel room, and we probably weren’t going to be able to afford to go to the lobby of the hotel in many of the episodes.

So I wanted to redesign that hotel hallway to bring in some of the architectural elements of the lobby. That way, every time you’re up on the 9th floor, you also have that feeling of that hotel lobby down below. Taura Rivera, the set designer on that set really nailed it and our construction team did such a nice job with all the wood and tile details and the fake elevators. I was pleased with all the changes we made. It shot really well.

Production design of “Briarpatch” by Richard Bloom.

Continue reading »

Continuing the ongoing series of interviews with creative artists working on various aspects of movie and TV productions, it is my pleasure to welcome Jessica Kender. In this interview she talks about the changes in the world of episodic productions in the last few years, being the guardian of the visual language on her productions, working with digital models, and willing to take more risks as time goes by. Around these topics and more, Jessica looks back at her earlier work on “Dexter” and “Medium”, and dives deep into creating the present and the past on Hulu’s “Little Fires Everywhere”, on which she did all the episodes.

Kirill: Please tell us about yourself and the path that took you to where you are today.

Jessica: I got my start in high school doing stage crew for different theatre shows. The person who was in charge of our stage crew came from Broadway, and we would put on these huge productions unlike what I’ve seen for theater for high school before.

When I applied to college, I wasn’t exactly sure what I wanted to do. I knew I loved doing stage crew, but I wasn’t sure if that was it. I remember standing there with two letters, one that was for Carnegie Mellon and one that was for Brandeis. Brandeis would have been more of a general BA, while Carnegie is a conservatory. I ended up putting Carnegie in. When I graduated, I didn’t have any other skills. It’s a conservatory, so literally all I knew how to do was set design for the theater.

I always wanted to do TV and I wasn’t even interested in features. As a little backstory, I grew up without a TV. My parents didn’t have one, so it was almost like a rebellion for me. It was that because we didn’t have one. When I would go to friends’ houses, no matter when, even in the middle of summer, I just wanted to watch TV. I didn’t care if it was a soap opera or something else. I just wanted to watch.

So when I graduated in set design, I had the skills to set design for theater, but I knew I wanted to get into television. So I worked in New York for two years doing theater and then doing industrials. And when I came out to LA, I was able to get into TV and I stayed there ever since.

Kirill: Would you say that most of your career so far has coincided with two big transitions in the world of TV, the first being the depth of storytelling, and the second being the transition to digital, high definition technology? If so, how has this affected what you’re doing?

Jessica: It’s fascinating. My first production design job was on “Medium”. There, we made the switch to high-def in the middle of shooting it. I remember people being terrified of how would the actors look. There was panic, and it 100% changed the quality of the work that we do.

When I originally started, we would put together flats. You would paint those flats and they would go up on TV. Once we switched to high-def, we did a plaster skim coat on every single set, because you didn’t want it to look like raw luan. And that translated for everything.

I was recently looking back at some of my “Medium” work. Some of it I’m very proud of still to this day, because we did a lot of fun stuff on that show. But from a set point of view, you can tell that’s an older show without even watching it. I’ve edited the pictures of those sets on my website and I’m still proud of that work, but when you go through them, you would see that it’s almost a more rudimentary or a slightly theatrical approach to production design and the way we built stuff back then.

Obsessive math professor’s apartment in “Medium”. Courtesy of Jessica Kender.

You’re right that it tied in with the fact that TV was starting to become the medium that was a lot more respected. It wasn’t just the formulaic one-hour dramas. After “Medium” I did “October Road”, and after that was “Dexter”. We played around on “Medium” and did some interesting ideas like plane crashes and flashbacks. But “Dexter” was the beginning of that boom.

Before “Medium,” I worked as an assistant art director on “The Shield” in 2003, and that was an FX show. That was also around the time the TV started changing, doing things that people didn’t see before. “The Shield” was based on the Rampart Police Department that was full of corruption. It was one of FX first signature shows, and all of a sudden you had the antihero but on TV. You almost never saw the antihero on TV before that time. Our leads were all corrupt, nasty people and viewers were fascinated. It delved into all sorts of stuff we didn’t see, but it took a while until you started seeing that everywhere.

Then all the premium cable networks started coming out and that just elevated everything. You had stories that weren’t meant to appeal to the general audience. Old TV had that more neutral flavor, because it had to make everyone happy. But once you had the premium networks working, you didn’t have to appeal to everyone, and you had more money. So we have this high-def coming along, and all of a sudden we have the money to back up the stuff we’re doing. Everything started to change. Everything started to look better.

On my very first union show as a production designer I was one of four people. And my art department on our current show is 11 people. Just the amount of people that you need to staff with shows the change that has happened.

Kirill: As the shows continue with the yearly schedules, is this why we’re seeing much shorter seasons, down from 22-23 episodes to 10-12, or even sometimes as few as 8?

Jessica: “Medium” was my only production design that was 22 episodes. “Dexter” had 12 episodes in each season. I just finished working on “Little Fires Everywhere”, and that was 8 episodes in 9 months. Back when I was on “Medium”, we did 22 episodes in 10 months.

So yes, we are doing less episodes, but we’re putting more into it. “Dexter” was still on an 8-day schedule. “Little Fires Everywhere” was between 11 and 15 days per episode, but the amount of prep that you do now for shows compared to back then is significantly more. You have more time to flesh out what you’re trying to say, to build all your sets, to really sit with everybody and figure out what is the look of the show.

In those early days you would come in, and start running and gunning. I was lucky if I had 6 weeks prep, while on the latest show I was on until it was shut down we had 14 weeks of prep. People have realized that TV is a different world now, and are treating it that way.

Indonesian motel room in “Medium”. Courtesy of Jessica Kender.

Continue reading »

Continuing the ongoing series of interviews with creative artists working on various aspects of movie and TV productions, it is my delight to welcome Jeffrey Waldron. In this interview he talks about how the changes in the world of episodic productions in the last few years, the dynamics of having one vs more cinematographers working on a season, building a visual language for the story and evolving it as the story progresses, and choosing his productions. Around these topics and more, Jeffrey dives deep into his work on Hulu’s “Little Fires Everywhere”. Fair warning – we did the interview right after Episode 6 aired, and there are plenty of spoilers throughout the interview on the storylines in the show.

Kirill: Please tell us about yourself and the path that took you to where you are today.

Jeffrey: I knew very early that I wanted to be a storyteller. As a kid, I was obsessed with animation. To me it was like magic, those earlier Disney films were like moving paintings. Now I have a daughter and I’m revisiting all of them, and they’re still just so beautiful. I loved the artistry and the control that the artists had over each frame in terms of balance, color, movement – complete mastery of what was in that box.

Jeffrey: I knew very early that I wanted to be a storyteller. As a kid, I was obsessed with animation. To me it was like magic, those earlier Disney films were like moving paintings. Now I have a daughter and I’m revisiting all of them, and they’re still just so beautiful. I loved the artistry and the control that the artists had over each frame in terms of balance, color, movement – complete mastery of what was in that box.

My experimentation in hand-drawn and stop-motion animation eventually put me face-to-face with a 16mm camera. From there my interest in film expanded and I started shooting still photos. I found I also enjoyed the documentary-style approach where you don’t have any of that control. Ultimately, it’s a combination of both of these elements for me – creating magic and finding magic, and in trying to combine those two interests, I realized I wanted to be a cinematographer.

In high school I started volunteering on indie film sets to learn lighting, to learn how a DP [director of photography] worked, how to use light meter and how to tell the story with camera and light. It was my passion, and when I graduated high school, I moved to LA to go to film school – and I’ve been here ever since.

Kirill: If I can bring you back to those first few times on the film sets, was there anything particularly surprising or unexpected for you?

Jeffrey: The surprising thing early on was just how much of a collaboration the whole thing was. I had started out making my own films, and especially coming from an animation background where you’re all alone, you’re doing it by yourself. When I started volunteering on a lighting crew, I started to realize that there was more to it than some grand vision at the top shared by a couple of key artists. There were so many talented hands in place making that image you see. It’s about how the light is shaped, it’s the way the painting is hung on the wall at exactly the right height for the composition, there are all these details in everything you see. I just love that kind of collaboration where everybody has a sense of what this can be and is working hard to make it the best version of that.

Cinematography of “Little Fires Everywhere” by Jeffrey Waldron.

Kirill: Is it hard to convey this organizational complexity when you talk about what you do for a living?

Jeffrey: I usually answer the question of what I do rather quickly, but there is of course a lot to it.

I think people know what a cameraman is, but I don’t think they know that there’s a role that is ultimately the shepherd of how they’re perceiving the work – in terms of light, color, composition, choices of depth of field and all these tools we have at our disposal. I don’t know that they know that those are all actually conscious choices, and that to pull off any of that stuff you need huge teams of skilled individuals.

You don’t want to take away from the magic of what the filmmaking is doing by explaining too much about what’s behind it. Hopefully that stuff is invisible. It’s the combined hard work of the crew members – the camera teams, the grip teams, the electric teams, the art department, wardrobe, and all of the other departments. But if the story is being told right, you hope most people feel that stuff rather than think about it.

Kirill: What do you see in the world of episodic productions in the last few years? Do you see higher expectations from the production side of things? Do you see that the audiences are expecting a higher level of storytelling?

Jeffrey: I think there’s a push from all sides to push the storytelling. The audiences expect more from the small screen than they ever have before. I think audiences now demand more depth in story and bolder cinematography. They see episodic more as a long-form feature than the TV shows we used to know.

I also see the showrunning side of it pushing the boundaries. If you’re a creator, there’s a huge competitive drive toward bigger and better. What can we do with this medium that we’ve never done before?

And then you have studios and networks like Hulu, Netflix and HBO that are driven from the top to outdo each other, to find new heights.

Cinematography of “Little Fires Everywhere” by Jeffrey Waldron.

Kirill: Do you ever want to hear a compliment that it was a well shot episode where people focus on your part of it and not on the story itself?

Jeffrey: Of course you want some recognition, but I think the better compliment is that the episode worked really well. Now you definitely don’t want to hear anything negative about it [laughs] but the best compliment you can hear is that it was amazing storytelling all around. If I can read that in a review, if I can hear that from somebody, then I know that we all did our part. You don’t want to stand out or be distracting in any way. You don’t want anybody to be thinking about cinematography.

Kirill: How do you choose your projects in general, and what brought you to “Little Fires Everywhere”?

Jeffrey: I had just come off of a production in New York called “Mrs Fletcher” that was based on a book. The author of the book was one of the producers and was heavily involved. There was something wonderful about trying to take the prose of a book and discover a visual representation of that. Is the book formal? Is it loosely written? How do we create the fabric of the book in this series?

So when another book adaptation came along on the heels of that, I was again inspired to try to bring it to the screen. I read the book before the interview, and I also read the first couple of scripts. The book was amazing but there was also a lot of additional depth that Liz Tigelaar the show runner brought to her interpretation in the scripts. It was exciting to me.

Beyond that, I’m a 90’s kid. My last three years of high school were in suburban Washington DC. We lived in a house very similar to Elena’s, in a world very similar to Shaker. I felt an instant connection and I knew throwing myself back there, tapping into memory to help create the visual story, was going to be fun for me.

Cinematography of “Little Fires Everywhere” by Jeffrey Waldron.

Continue reading »

Continuing the ongoing series of interviews with creative artists working on various aspects of movie and TV productions, it is my pleadure to welcome Meghan Kasperlik. In this interview she talks about changes in the world of episodic storytelling in the last few years, technology advancements and what they mean to costume department, conversations around creating costumes that tell stories, and what happens behind the glamorous curtain of these productions. Around these topics and more, Meghan dives deep into what went into the first season of the highly acclaimed “Watchmen”.

Kirill: Please tell us about yourself and the path that took you to where you are today.

Meghan: My name is Meghan Kasperlik and I’m a costume designer for TV and film. I started out being fascinated with film when I was young, I loved watching movies. But back then, as a child, I never really knew that there was a possibility of working in the movies.

Meghan: My name is Meghan Kasperlik and I’m a costume designer for TV and film. I started out being fascinated with film when I was young, I loved watching movies. But back then, as a child, I never really knew that there was a possibility of working in the movies.

I grew up in the Midwest, so it wasn’t something that I thought was obtainable for a long time. When I got into high school, I became more interested in fashion and I thought I would be going into the fashion industry. When I was in college, I majored in fashion merchandising with a plan to go to New York. When I got to New York I was working in fashion PR and as a stylist assistant, working my way up to stylist for different projects, in commercials, magazines, etc.

I was styling and doing PR, and my roommate at the time said that a television show he was working on needed a costume production assistant. I asked him who was the costume designer, and not that I would have had much of a choice at the time, but it happened to be Patricia Field, the Costume Designer for “Sex in the City”. It was an exciting opportunity. I interviewed and I got the job as the costume PA. Since then I have worked my way up from the bottom.

I worked in the costume department with Patricia Field for 3.5 years, going from costume PA to the costume coordinator to the assistant designer. Then I started working with other people as the assistant designer, and then started designing.

Costume design for 7th Kavalry on “Watchmen” by Meghan Kasperlik.

Kirill: If you look back at your first few experiences in the TV and movie world, was there anything particularly unexpected or surprising for you?

Meghan: When I was on a photo shoot for a fashion spread, there’s a large number of people involved. But it’s an editorial, so it’s much more contained. There’s not as many people building the sets on-site or not as many camera people. So when I got to be on film production, just to see the amount of crew in each department was fascinating to me. I learned about a lot of other departments and what everyone was doing and seeing that was educational because I learned so much. I’m a person who tries to absorb as much as possible within the setting, and so that was fascinating. It made me more interested in TV and film.

Because I had a number of years of experience in the fashion industry, that definitely helped me work at a fast pace and understand the pace of TV and film. That wasn’t a struggle or anything, but I definitely was able to utilize that to be able to achieve what I wanted to within each project.

Kirill: Is there anything that still manages to surprise you when you join the new production?

Meghan: Anything is possible [laughs], but I don’t know if anything really surprises me anymore. You have to expect the unexpected. Sometimes projects are achieved with a lot of work. It might be a bit surprising at first, but the magic of television is pretty remarkable. Not much shocks me. I’m un-shockable [laughs].

Costume design for the flashback sequence on “Watchmen” by Meghan Kasperlik.

Kirill: You started in the TV world, then you were in the feature film world, and now you’re back in the TV world again. How much has this world has changed in the last 5-6 years?

Meghan: Television programming has evolved, and streaming services have definitely changed the game. So many more people are staying home to watch content that’s really interesting. It’s not just the Thursday night programming that was the must-watch. Now there’s must-watch television whenever you want. There’s a lot more content happening in television, especially with streaming services.

And there’s a lot more smart content happening. When I first started, it felt that people watched it to be entertained. But now I feel that much more of the content in TV now is making people think – and think outside the box. People are watching anything from dark comedies and dramas to documentaries, documentaries that are turning into features turning into miniseries. That is fascinating and there’s much more of a platform for a lot more ideas. That huge growth helped the industry, but it also made people aware of smart content – which I think is important.

Kirill: As technology evolves, viewers at home can afford getting much better and bigger screens, and the productions themselves are constantly pushed to use higher-resolution digital cameras. And on top of that, viewers are probably getting used to expecting that “cinematic” feel from the episodic shows they’re watching. Does that make your job more complicated?

Meghan: I’m looking at the last few years, and each year that I’m in this business it becomes more and more apparent that the costume has to be prepared to be seen at all angles. Just because it’s written a certain way in the script does not mean that that’s way the way that it will be filmed and shot for television or for film. I need to ensure that every angle that the camera could be on that costume has to have everything in place – the correct color, texture, fabric. All of it has to be able to be seen on camera.

You can’t say that they’ll never see that button or the back of the waistband of the pant. They will see it at some point.

So while I’m creating the costume and checking it in the fitting to see the angles, that is definitely something I have to be more aware of. It also makes it more exciting. Now we’re seeing design details that maybe we didn’t see 10 years ago because of the way that the television programming is being filmed – like you said in more of a cinematic element. So it is very important to make sure that it’s all looking like it should at all angles.

Costume design for Hooded Justice / American Hero on “Watchmen” by Meghan Kasperlik.

Continue reading »

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()