There’s a lot of hand-wringing around the changes Verizon corporate is bringing down on the Tumblr communities. People are talking about the freedom of creative expression, the future of safe spaces for fringe interests and the good old days before the engagement-driven ad “opportunities”. Yahoo’s billion-dollar purchase of the not-quite profitable platform was accompanied by grand promises:

We promise not to screw it up. Tumblr is incredibly special and has a great thing going. We will operate Tumblr independently. David Karp will remain CEO. The product roadmap, their team, their wit and irreverence will all remain the same as will their mission to empower creators to make their best work and get it in front of the audience they deserve. Yahoo! will help Tumblr get even better, faster.

…

In terms of working together, Tumblr can deploy Yahoo!’s personalization technology and search infrastructure to help its users discover creators, bloggers, and content they’ll love. In turn, Tumblr brings 50 billion blog posts (and 75 million more arriving each day) to Yahoo!’s media network and search experiences. The two companies will also work together to create advertising opportunities that are seamless and enhance user experience.

There’s a certain beauty in the natural cycles of web chaos. And there’s also a big difference between sustained and sustainable. The history so far has shown that it is not a sustainable endeavor to build a popular social platform that is held in high esteem by both users and the market forces. It’s a rather awkward place between being a sustained loss center, and being stuck in a somewhat unsavory self-reinforcing cycle of business decisions that go counter to the whole notion of, well, social.

As for me, with the impending shuttering of Google+, I’ll be writing more right here in my own little web garden.

Software is never quite done. Even if you have all the features put in, and all the known bugs fixed, if you stand still, the world will slowly pass you by and leave you behind.

A modern app is, more or less, expected to be everywhere. People expect seamless sync between all their devices, intelligent offline, presence of all the screens in their life, and constant adaptation of how the app behaves to the ever-evolving world of technology that we live in.

The same goes for web sites. Space Jam is a rather wonderful memento of the early web frozen in time. But it’s a curiosity, a rare peek into the world of yesteryear.

Content is king they say. Whoever they are, they don’t tell you that the presentation of content matters. As I was switching my site to be fully HTTPS earlier in the year, I was reminiscing on all the non-content maintenance work that I keep on doing on a semi-regular basis with my site to keep up with the latest and greatest. To keep up with what is “expected” of modern web sites. To get a feel of the burden the technology evolution is placing on hundreds of thousands (millions, tens of millions?) of web developers that find their carefully constructed houses of cards gather cobwebs.

- In 2012 I’ve switched to using web fonts, and I kept on tweaking those ever since – for body, headings and navigational elements.

- In 2013 I’ve switched to fully responsive design, scaling the overall layout to behave well on a variety of screen sizes.

- In 2014 I’ve switched to use 2x / retina images on relevant hardware, which required going back to the archives and resourcing all the images in the interviews that have been published until then.

- In 2015 I’ve switched to a single-column layout, rearranging the content to flow better across a variety of screens.

- In 2018 I’ve switched to HTTPS, even though the only user-facing input box is the search tucked at the very end of the page.

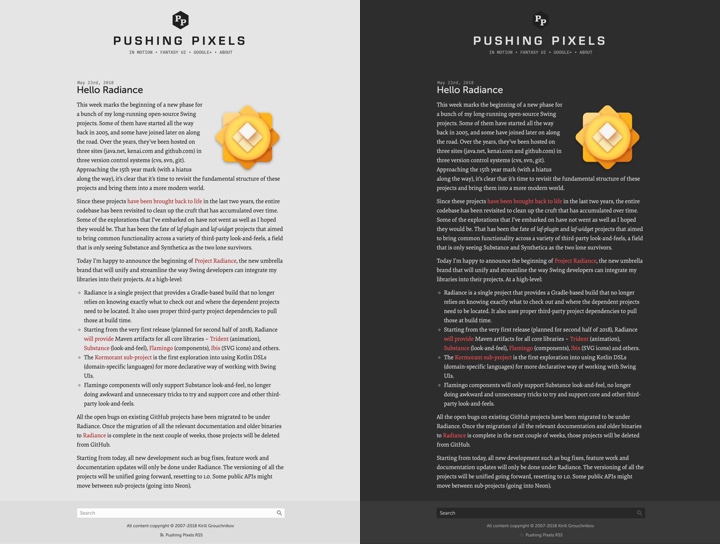

Is the latest 3 year gap an indication that things are slowing down? Maybe. But probably not. I’m still tending this little web garden of mine. The latest chapter, so far, has been adding support for dark mode:

On the left is the regular version of Pushing Pixels. On the right is how it looks like running under Safari Technology Preview on the latest macOS 10.14.1 (Mojave), with the work under way to add the matching CSS selector support to Firefox and Chrome.

I hope this little web garden of mine will be there in 10 years. In 20 years. Hopefully in 40 years. There’s a lot of tending ahead.

Note: since this post was written, Safari for macOS 10.14.4+ and Firefox 67+ have added official support for dark mode. Chrome has added support for dark mode starting in 73 on Mac and starting in 74 on Windows.

It’s been a few busy months since the announcement of Project Radiance, the new umbrella brand that unifies and streamlines the way Swing developers can integrate my libraries into their projects. Some of those projects have started all the way back in 2005, and some have joined later on along the road. Over the years, they’ve been hosted on three sites (java.net, kenai.com and github.com) in three version control systems (cvs, svn, git). Approaching the 15th year mark (with a hiatus along the way), it was clear that time has come to revisit the fundamental structure of these projects and bring them into a more modern world.

At a high-level:

- Radiance is a single project that provides a Gradle-based build that no longer relies on knowing exactly what to check out and where the dependent projects need to be located. It also uses proper third-party project dependencies to pull those at build time.

- Starting from the very first release, Radiance provides Maven artifacts for all core libraries – Trident (animation), Substance (look-and-feel), Flamingo (components), Photon (SVG icons) and others.

- The Kormorant sub-project is the first exploration into using Kotlin DSLs (domain-specific languages) for more declarative way of working with Swing UIs.

- Flamingo components only support Substance look-and-feel, no longer doing awkward and unnecessary tricks to try and support core and other third-party look-and-feels.

It gives me great pleasure to announce the very first release of Radiance, appropriately tagged 1.0.0 and code-named Antimony. Lines of code is about as meaningless a metric as it goes in our part of the world, but there are a lot of lines in Radiance. Ignoring the transcoded SVG files auto-generated by Photon, Radiance has around 208K lines of Java code, 7K lines of Kotlin code and 5K lines of build scripts.

It gives me great pleasure to announce the very first release of Radiance, appropriately tagged 1.0.0 and code-named Antimony. Lines of code is about as meaningless a metric as it goes in our part of the world, but there are a lot of lines in Radiance. Ignoring the transcoded SVG files auto-generated by Photon, Radiance has around 208K lines of Java code, 7K lines of Kotlin code and 5K lines of build scripts.

It’s been a long road to get to where Radiance is today. And there’s a long road ahead to continue exploring the never-ending depths of what it takes to write elegant and high-performing desktop applications in Swing. If you’re in the business of writing just such apps, I’d love for you to take this very first Radiance release for a spin. You’ll find the prebuilt dependencies in the /drop/1.0.0 folder, and if you fancy a more proper dependency management mechanism, there’s an answer for that as well . All of them require Java 8 to build and run.

There’s a bunch of helper extension methods that the Kotlin standard library provides for working with collections. However, it would seem that at the present moment <a href="https://kotlinlang.org/api/latest/jvm/stdlib/kotlin.collections/java.util.-enumeration/index.html">java.util.Enumeration</a> has been left a bit behind. Here is a simple extension method to convert any List to a matching Enumeration:

/**

* Extension function for converting a {@link List} to an {@link Enumeration}

*/

fun <T> List<T>.toEnumeration(): Enumeration<T> {

return object : Enumeration<T> {

var count = 0

override fun hasMoreElements(): Boolean {

return this.count < size

}

override fun nextElement(): T {

if (this.count < size) {

return get(this.count++)

}

throw NoSuchElementException("List enumeration asked for more elements than present")

}

}

}

And here is how you can use it to expose the local file system to the JTree component. First, we create a custom implementation of the TreeNode interface:

data class FileTreeNode(val file: File?, val children: Array<File>, val nodeParent: TreeNode?) : TreeNode {

constructor(file: File, parent: TreeNode) : this(file, file.listFiles() ?: arrayOf(), parent)

constructor(children: Array<File>) : this(null, children, null)

init {

children.sortWith(compareBy { it.name.toLowerCase() })

}

override fun children(): Enumeration<FileTreeNode> {

return children.map { FileTreeNode(it, this) }.toEnumeration()

}

override fun getAllowsChildren(): Boolean {

return true

}

override fun getChildAt(childIndex: Int): TreeNode {

return FileTreeNode(children[childIndex], this)

}

override fun getChildCount(): Int {

return children.size

}

override fun getIndex(node: TreeNode): Int {

val ftn = node as FileTreeNode

return children.indexOfFirst { it == ftn.file }

}

override fun getParent(): TreeNode? {

return this.nodeParent

}

override fun isLeaf(): Boolean {

val isNotFolder = (this.file != null) && (this.file.isFile)

return this.childCount == 0 && isNotFolder

}

}

Note a few language shortcuts that make the code more concise than its Java counterparts:

- Since

File.listFiles() can return null, we wrap that call with a simple Elvis operator: file.listFiles() ?: arrayOf().

- The initializer block sorts the

File children in place by name.

- To return tree node enumeration in

children(), we first map each File child to the corresponding FileTreeNode and then use our extension function to convert the resulting List to Enumeration.

- Looking up the index of the specific node is done with the existing extension

indexOfFirst function from the standard library.

Now all is left to do is to create our JTree:

val tree = JTree(FileTreeNode(File.listRoots()))

tree.rootVisible = false