Select file

Invoke the copy operation

Select destination folder

Invoke the paste operation

The sequence of steps to copy a file to a different folder is now so ingrained in my motor memory that I don’t question why the steps have to be in this specific order. You select something, and then you “say” what you want to do with it. It only “feels” natural because we’ve been doing it for so long.

In English you would say “Copy A to B” when you’re asked to describe what you’re doing. But when you actually do it, it’s “A copy B to”. Sort of a reverse Polish notation in a sense. But following the rules on English grammar only makes sense if you insist that the sequence of actual steps must conform to those rules no matter what is the local dialect. In English, the only way to say this is “Copy A to B”. But in Russian, you can use any one of the following:

- Copy A to B

- A copy to B

- To B copy A

- Copy to B A

- A to B copy

- To B A copy

Here the only thing that stays the same is “to B”. We end up with 3 parts of the sequence and 3! ways to combine them. To a native speaker the end result is the same, but the importance is conveyed by the order. The part that comes first is the more important, and the part that comes last is the least important. There is a strong implicit importance relayed by the ordering.

But I wouldn’t really expect a localized version of Windows, OS X or Linux to allow me to do all six possible sequences to copy a file to a different folder. Ignoring the vast complexity of supporting something like this for all possible languages and dialects, it’s quite counter-productive to expose radically different ways to achieve the specific result depending on the specific natural language of the user. Or is it?

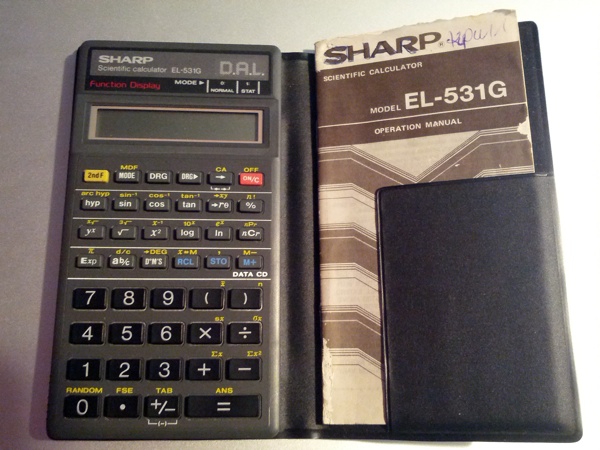

I had a little obsession with calculators growing up. I actually had only two, but I’ve spent an inordinate amount of time doing various tricks with them. The first one was of the usual variety. Every math operator was an implicit “equals”. If you did 2+3×4, you got 20. If you wanted to do a sine of 30, you did 30 sin. It’s only weird to have these differences if you stop thinking about it. It’s perfectly logical to have these differences if you grasp at least the basic complexities of implementing a simple calculator in your starter programming language of choice.

And then there was Sharp EL-531G with its D.A.L. – Direct Algebraic Logic. The way to compute something was to start typing the same exact sequence as you have in your problem. Sine of 30 is sin 30. 2+3×4 is evaluated only when you press = and then you get 14. The small downside is that if you’re typing quickly and don’t check every single operand, you won’t discover “obviously” wrong intermediate results. The much bigger upside is that you don’t start mentally regrouping parts in a complex formula just to fit the implementation model. The computation follows the rules of precedence, and you also have the brackets to control it if necessary.

The notion of fluent interfaces became quite popular a few years ago. In the “regular” object-oriented approach, copying a file would look something like this:

FileRef reference = new File(“path/to/A”).copy();

new File(“path/to/B”).paste(reference);

With a fluent interface, it would become something like this:

FileUtils.copy(“path/to/A”).to(“path/to/B”);

Where FileUtils.copy would return an object that has a to method that does the actual copying of the bits. Fluent interfaces are often tweaked and judged on the merits of how close they get to the rules of English grammar, with various techniques to encapsulate the complexities of chain links that arise because of that.

But what if I’m not an English speaker? A fluent interface based on the rules of English grammar is no more understandable or fluent, if you will, if it doesn’t follow the rules of my native grammar. You’re just trading one convention over another. Long chains of fluent calls are also counterproductive to handle failures. If you have more than one link, how do you handle and debug failures? Should a failure at a middle link roll back the results of the previous links? This also brings another interesting point which goes back to N! variations allowed by the rules of Russian grammar. If a native Russian programmer exposes a fluent API that allows all possible variations, does it mean that the implicit importance of the order affects how you handle intermediate failures?

It would be weird if I had to first press Cmd+C and only then to select a file to start the copy process. It would be equally weird to press Cmd+V and only then to select the target folder. How would you even “tell” to the computer that you are at the target folder and not in the middle of navigating to it by clicking around? But it’s only weird because of the 20-year strong rule of WIMP interaction model.

If you move away from files organized in folders towards files tagged by labels, things become different. If you move away from action “verbs” denoted by commands on the selected object toward a more fluent voice-controlled interaction, things become different. If you move away from the very notion of files as boundary units delineating your data, things become different. How different? I don’t know. But the next 20 years will be quite interesting.

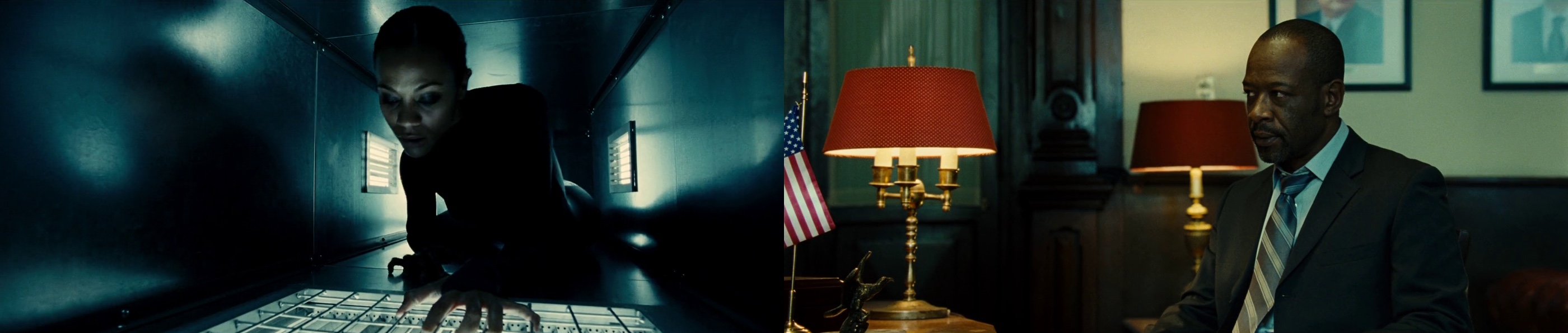

The explosively fast-paced “Colombiana” follows Zoe Saldana on a deadly mission to avenge the murder of her parents. The visual look of the movie is defined early on with earthen browns, ochre yellows and desaturated emerald greens as perfectly illustrated in this outdoors shot. Note how not only the bodyguards, but the entire house seem dwarfed by the overbearing automobile, foreshadowing the quick murder of the three men and the impending disaster for the young Cataleya.

Slightly further in the same scene Jordi Mollà‘s character tries to appear not overly menacing, as the space between him and Cataleya is lit with soft yellows of the natural daylight. However the much darker space behind his head and the positioning of his face to be to the left of the top-right rule of thirds spot hint at the sinister ulterior motive of his visit.

The movie jumps forward in time to see Cataleya as a cold-blooded assassin that shares time between hit jobs overseen by her uncle and exacting revenge on people connected to the murder of her parents. There’s an interesting visual connection between the establishing shots of Bogota and Chicago – similar shooting angles and color treatment suggest similarity in the corruption of law enforcement agencies and prevalence of street violence:

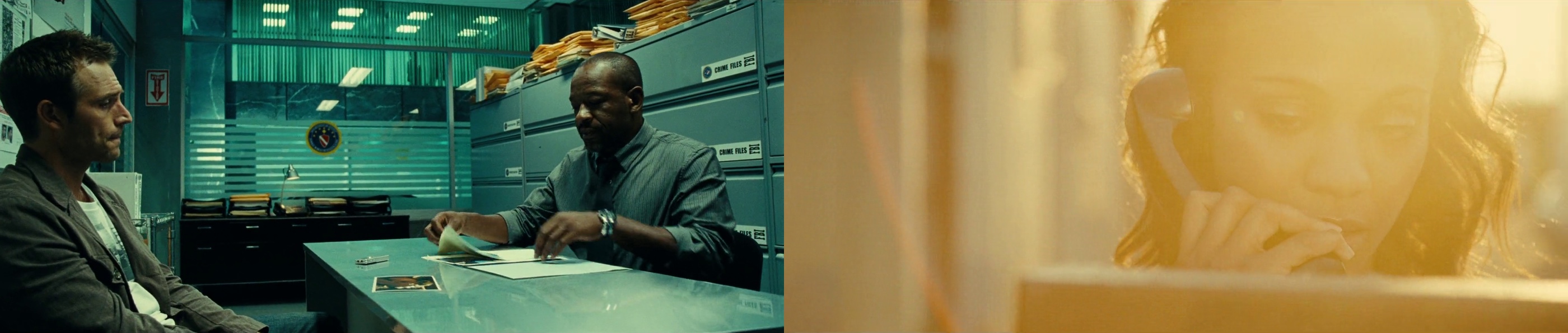

Most of the inner spaces involving the local police sets add chrome blue to the palette. In the left shot blue is created when the fluorescent whites bounce off of the inner metal walls of the ventilation shaft, while the right shot features extensive use of light blue on background elements:

In the next shot of a coroner examination room blue is assimilated into the green to bathe the entire set in an almost monotonous drape of washed out turquoise. The position and alignment of the camera are coupled with a wide-angle lens to distort the depth, enhancing the perceived distance along the Z axis and distancing the viewer from the police officer in charge of investigating a string of murders. Note that despite positioning the three characters directly in the middle of the frame, our eye is guided by the perspective lines towards the far right corner of the room, all the while masking the technician with a deftly placed lighting device.

In one of my favorite sequences Cataleya goes into a book shop (or library) to be confronted by her angry uncle. The camera “welcomes” her at the door and then tracks her from behind as she makes her way across the shop floor. A fleeting cut to the bottom part of her legs reinforces her projected composure and determination:

It gives me great pleasure to have Colombiana’s director of photography Romain Lacourbas answer a few questions I had about this movie.

Kirill: Tell us a little bit about yourself and your professional background

Romain: I studied art history for a couple of years in University and then joined a cinema school in Paris. Before my graduation I had the chance to be chosen as a trainee on a feature with the cinematographer Pierre Aïm. I went on to work as camera assistant, focus puller, camera operator and finally DOP [director of photography] for second unit on feature films. At the same time I was also DOP on short films, particulary with Lola Doillon. When she directed her first feature, she call me to be his DOP. It was the beginning of my DOP carrer.

Kirill: In your opinion what are the most important parts of the craft of cinematography?

Romain: Listening is the first thing you have to deal with to understand the vision of a director, and to be able to help him/her reaching the visual aspect that is going to serve the script. Finding the visual look according to the script and the director is a really important part of the work. It is also one of the most interesting and challenging parts of pre-production. Being open-minded and capable of changing what was planned, because a shooting is full of surprises, is also necessary. A good knowledge of all technical aspects (optical, lighting, grip) is also necessary to propose solutions during pre-production work as well as on the set.

Kirill: How much different it is to work on feature films, commercials and music videos?

Romain: Working on a feature film is like doing a marathon. You have to endure. Commercials and music videos are a great pool to meet young directors and they have really interesting artistic confrontation. In the meantime, due to higher budgets commercials give us a chance to test new equipment and new tools.

Kirill: Can you describe the process of defining the visual look of “Colombiana” before the shooting started?

Romain: Olivier Megaton (the director) and went over a lot of feature references, particularly including Tony Scott’s features. We also made different kinds of tests with different optical setups and filters in order to polish the right look.

Kirill: “Colombiana” was shot on film. What drove this choice?

Romain: Olivier and I were convinced (and we still are) that digital cameras – unless a huge post-production work is involved – can not render the same highest quality as the film. A film’s image gets instantly more body, character and texture. To reach the same goal digital tools require a bigger intervention in post-production. Moreover, in terms of logistics, such as shooting Colombiana with the rhythms, the number of cascades, and the regular presence of multi-camera setups, might have been a hindrance during the shooting.

Kirill: On a related note, what are your thoughts on shooting digital?

Romain: I think this is a great way for smaller productions which allows the director to not be concerned about the film dailies. It also opens up many possibilities in regards to special effects. This is a medium that requires a different approach and method of work (compared to the film) but which nevertheless remains really interesting and creative.

Kirill: “Colombiana” has a few well defined color palettes. Does a limited color palette affect your choice of lighting and composition?

Romain: We tried to assign colors to each place. So, there are few different colors within the same scene but one chosen tone for the set. We used relevant lighting equipment – tungsten, HMI, fluorescent lights, balloons etc – to match the desired effect.

Kirill: There are a lot of scenes involving heavy weapons. How much time was spent on set on training and safety, and how did that affect your shooting schedule?

Romain: Zoe Saldana was trained a long time before the shooting started by our gunsmith team. In addition, Christophe Maratier’s team are all seasoned professionals who are used to work on feature films. They are very fast. We never had to wait for the weapons during the shooting. Also, during the preproduction meetings we all knew exactly how we were going to shoot those sequences so that everything was well prepared upstream.

Kirill: What was the scale of construction and destruction in the New Orleans house where the final shootout took place?

Romain: The interior of the house was rebuilt on stage. By the end of the shooting it was almost all destroyed…

Kirill: The chase after the ten-year old Cataleya through the streets of Bogota was such a thrilling scene. How much time did you spend setting up, shooting and editing it?

Romain: One shooting week.

Romain Lacourbas on the set of “Colombiana”.

Kirill: Do you see your craft affected by either shooting or post-converting in 3D?

Romain: I didn’t get the chance to shoot in 3D or do post-production conversion to 3D. I would consider my work differently starting from the pre-production when that happens.

Kirill: Finally, can you recommend a few of your favorite productions that have particularly impressed you over the years?

Romain: It’s always hard to answer this question, because either you forget a lot of examples or you spend a month trying to make a precise ‘list’. But here are some features on which I found the cinematography impressing and related to the narrative aspects :

« Brooklyn’s finest » by Antoine Fuqua

« Thunderbolt and lightfoot » by Michael Cimino

« Dog day afternoon » By Sidney Lumet

« He got game » by Spike Lee

« Roads to perdition » by Sam Mendes

« Amores perros » by Alejandro Gonzales Inarritu

« Mr Nobody » by Jaco Van Dormael

« Goodfellas » by Martin Scorcese

« Little Odessa » by James Gray

« 127 hours » by Danny Boyle

« Bullhead » by Michael R. Roskam

« Bronson » by Nicolas Winding Refn

« Gerry » by Gus Van Sant

(…)

And here I would like to thank Romain Lacourbas for finding time in his busy schedule shooting “Taken 2” and for graciously agreeing to this interview.

![]()