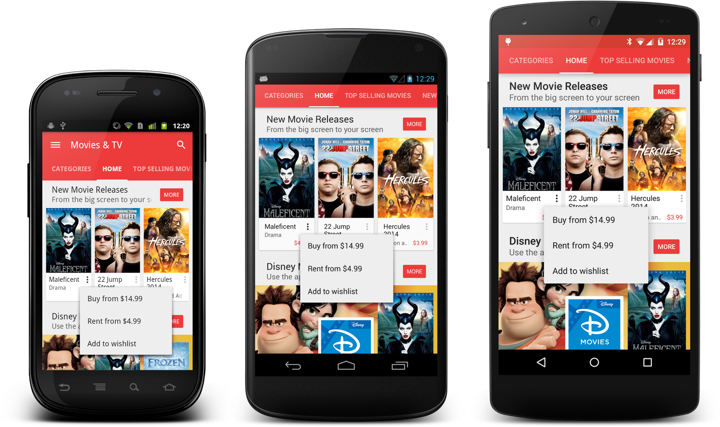

One of the more useful things that was “graduated” from the internal package in the latest drop of support libraries is ListPopupWindow.

No more need to try and emulate the look and feel of a popup window with a custom styled and positioned dialog for older platform releases.

Use R.layout.abc_popup_menu_item_layout for platform-consistent appearance (text style, margins, regular / ripple highlights) in your list adapter. Then set it with ListPopupWindow.setAdapter, optionally register a dismiss listener (note how the overflow dots for the “active” popup are darker), set anchor view for properly positioning the popup, compute the content width based on the content of your list, optionally mark it as modal so that it can be dismissed by tapping outside and don’t forget to call show().

Continuing the series of interviews with designers and artists that bring user interfaces and graphics to the big screens, it’s an honor to welcome David Sheldon-Hicks of Territory Studio. Prior to founding the studio in 2010 David has worked on “Casino Royale” and “Dark Knight”. Since then, Territory’s work can be seen in movies as diverse as “Zero Dark Thirty”, “Jack Ryan: Shadow Recruit”, “Prometheus”, “Guardians of the Galaxy” and the upcoming “Jupiter Ascending”. In this interview he talks about collaborating with the director, the art department and the VFX department throughout the different stages of a production, staying true to the look of the specific production such as aerial tracking in Zero Dark Thirty or high-tech science of Prometheus, the approach he’s taking to design futuristic interfaces, the physicality of technology around us and how it projects into his latest work on Guardians of the Galaxy, and the diverse gamut of projects Territory is working on and how they feed into each other.

From left to right: Peter Eszenyi, Nick Hill, Marti Romances and Ryan Rafferty-Phelan of Territory Studio at work on Guardians of the Galaxy.

Kirill: Please tell us about yourself and what you do.

David: I set up Territory in 2010 together with Lee Fasciani and Nick Glover. Having met while on a project, we wanted to work together and Territory seemed like a good name to describe our ambitions to carve our own path in the competitive creative sector here in London.

I’m Creative Director of Motion, with a background in graphic design, moving image and motion graphics – cutting my teeth in music videos before moving onto films, computer games and TV commercials.

I’m Creative Director of Motion, with a background in graphic design, moving image and motion graphics – cutting my teeth in music videos before moving onto films, computer games and TV commercials.

The studio combines a number of disciplines under one roof – motion graphics, animation and live action production, branding and UI across print and digital (web, mobile, tablet) and with the recent addition of Luke Miles as Director of Brand Experience, we are able to help brands engage audiences more affectively through physical and non-physical (service) design.

While that sounds like a strange mix, what ties it all together is our shared creative focus on human interaction, and future and near future challenges.

Film and gaming is really my heartland. Our first computer game project was for EA on “Medal of Honor”, which was one of the newer titles in 2010. They were going for a more “Modern Warfare” type of a game, and wanted an opening cinematic to tell the background story of why you [the player] were going to war.

Our first feature film project was “Prometheus” – a historic moment for Territory. Out of the blue we got a phone call from someone who wouldn’t tell us what the project was but it sounded interesting enough so we signed a couple of NDA’s. Then we were told that we’d be working on computer screen graphics for a new Ridley Scott film that was going to be a prequel to the Alien universe – at which point we freaked out. I’m a personal fan of Ridley Scott, and Ron Cobb’s universal language and iconography for the original Alien movie is held in very high regard in the design community. So to have the opportunity to explore that at an early stage was really exciting. The project itself has defined Territory’s approach to on-set screen graphics.

Kirill: And before Prometheus you worked on a couple more movie productions.

David: Yes, as a freelancer I worked on “Casino Royale” and “Dark Knight”. Both those projects were amazing and I loved the challenge and excitement of communicating complex concepts in a brief moment of pure user interface design that is also an intrinsic part of a sound stage environment that the actors engage with!

As Territory has grown, our user interface work for films has grown and developed as well, and we approach it as a discipline in its own right. We get different unique briefs and each one is a creative challenge. The beauty is in the idea of considering user experiences and interactions without the constraints of how you might build it. Sometimes it’s high tech, sci-fi future-thinking user interface, narrative thinking in computer games, or exploring future applications for tech giants such as Sony, Samsung or Microsoft.

We now find that the conceptual approach that we bring to film work appeals to other clients.

Tracking overlays for Jack Ryan: Shadow Recruit. Courtesy of Territory Studio.

Tracking overlays for Jack Ryan: Shadow Recruit. Courtesy of Territory Studio.

Kirill: What about Zero Dark Thirty and Jack Ryan? Was it just you, or was it done by the Studio?

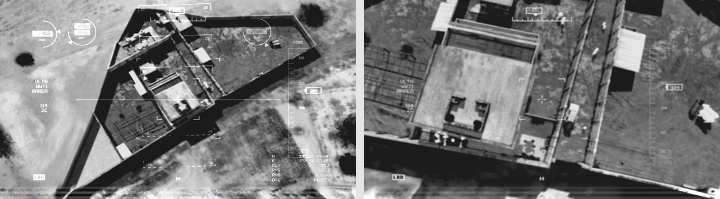

David: That was completed by Territory, rather than by me as an individual. We did “Zero Dark Thirty” after Prometheus, and it was at the opposite extreme in terms of sci-fi versus real-world narrative. It had to be very real and very authentic. There were a couple of visual effect shots but most of the computer screen graphics were on-set playbacks. The large screens where they’re looking at the Predator drone footage and reviewing aerial photography were all CGI plates that we had built and rendered in Cinema 4D, referencing data from Google Maps and then projecting on-set live for the actors to perform against.

We worked on two aspects of “Jack Ryan”; we created a lot of on-set graphics, and we also created what is called an ‘original content’ trailer. We took footage from the theatrical release trailer and did something unique with it – using hard overlays and surveillance technologies to suggest a narrative and suggesting background for some of the characters. In effect, we were using our UI graphical language both to set-dress the film and to advertise it.

Kirill: And for this type of movie your main constraint is that it’s very much rooted in the current technological world.

David: Definitely. Case in point, on Zero Dark Thirty I believe we had CIA signing-off on how realistic our work was, and what we could say to be true. For instance, we looked on Google Maps to see what the compound where Osama Bin Laden was hiding in looked like, and they asked us to change it to a degree so that it wasn’t exactly the same. There was online photography of the helicopter that crashed, and we approximated it as a 3D model and, again, changed it a bit for fictional purposes. It was an interesting, if delicate, balance to strike. And of course we had a typical sign-off from the art department – normal sources other than the CIA!

Control center from Zero Dark Thirty. Courtesy of Territory Studio.

Aerial footage from Zero Dark Thirty. Courtesy of Territory Studio.

Continue reading »

When I first spoke with the cinematographer Jonathan Freeman ASC in late 2011, it was primarily about his work on feature films. Since then he has worked on a number of HBO television productions, including “Game of Thrones” and “Boardwalk Empire”. In this interview Jonathan talks about the disappearing world of mid-budget adult feature drama and the migration of creative talent into the television world, defining and evolving the visual look of a series in collaboration with multiple director / cinematographer crews, an almost-continuous seasonal cycle of high-quality adult drama series, his close collaboration as a director of photography with VFX department on the effects-heavy “Game of Thrones” and working on tighter-scripted story arcs that span entire seasons.

Kirill: As a viewer I’m seeing a lot of quality adult drama productions writing, as well as high-profile cast & crew, moving from the feature world into the TV world in the last few years – including “Game of Thrones” and “Boardwalk Empire” that you’ve been working on. Is that what you are seeing as well from within the industry?

Jonathan: Generally speaking I prefer the shorter format of movies. Telling a concise story, within a couple of hours, more or less, is something that I always aspire to. However I’m always drawn firstly to the content of the script. The difference of quality between features and television scripts that I’ve been exposed to lately, is quite surprising. There’s been such a great improvement in television writing to the point where one could argue that the best writing is currently in TV. You’re starting to see now how the success and popularity of TV shows overshadow some of the major film releases. If the old water cooler is any gage, people seem to talk about popular TV shows on Monday mornings more often than the latest blockbusters.

You’re also seeing a migration of highly sought-after filmmakers desiring to make a leap into television. Part of that is probably financial, but I think there are two aspects on the creative side. The first is the opportunity to tell a longer story, which is something unique. And the other is that the material presented to them is quite exceptional. As for myself, I continue to choose my projects based on the quality of material rather than the medium itself.

Kirill: And there’s not much mid-budget drama being done in feature world.

Jonathan: That’s very true. There seems to be a void between ultra low budget films and tentpoles. The middle-sized budgets – from $15M to $40M – are rarely being made currently. You’ll occasionally come across a couple here and there that were built up through some unique financing. But it seems like mid-range films, for the moment at least, are not profitable investments for the studios.

Hopefully these are cycles that may come back. There was a period a few years back where films recognized by the Academy awards were independent ones in that $15M-$40 range, gaining interest from the Oscars as well as at the box office. That seemed to go away when tentpoles and the ultra-low budget horror movies became very financially successful.

Continue reading »

Continuing the ongoing series of interviews with creative artists working on various aspects of movie and TV productions, today I’m honored to welcome Michael Goldman. After starting his career in the commercials department at Industrial Light & Magic, Michael’s work has spanned a variety of TV and feature productions which, in the recent years, included Iron Man, The Amazing Spider-Man and Star Trek: Into Darkness. In this interview he talks about the shifting balance between physical and digital aspects of movie-making, from balancing budgets to building sets to shooting and augmenting individual scenes, as well as his thoughts on how the craft of art direction and production design should evolve and adapt in the world that shifts increasingly more work into the post-production stage.

Michael Goldman.

Michael Goldman.

Photography by Mark Redmond.Kirill: Please tell us about yourself and your path so far.

Michael: My name is Michael Goldman, and I work as a production designer and art director. I came to the industry in a roundabout way. I completed my master’s degree in architecture, and started working in architecture firms in New York and then Seattle, but it wasn’t the best fit for me so I tried the art world next, working for artists that did large scale public art projects. That’s where I got my art director skills, working on drawings and making presentations and then helping to build the final pieces. I drafted plans, worked in metal, wood and concrete bringing artist’s ideas to life. After about 5 years of that, I found my way into the film industry.

I was working in Seattle for the artist Buster Simpson, and “Sleepless in Seattle” was being shot there at that time. They were building a huge set for the top of the Empire State Building scene, and the production was hiring every carpenter they could find in Seattle to build it’s huge raised deck in a short period of time. I was looking for work, because Buster didn’t have any projects at the time, so I jumped at the opportunity. At the time, it was just a way to pay my bills until the next art project came along.

While working on that show, I visited the art department and started looking at the drawings of the sets that we were going to build, and I thought to myself, I can do this and this is what I was did during my architectural work. So I started exploring the possibility of drawing for films and began talking to people in the industry and trying to make some contacts.

After I had 3 or 4 names and numbers, I went to LA, sent out a lot of resumes, made follow up calls phone calls and slowly made my way into it. In the film industry if you are reliable and work hard, like any job, you will get rehired and work continuously. You can work your way up pretty fast. I was lucky that I met some helpful people and had some good opportunities. Suddenly it’s almost twenty years later and I don’t know where the time has gone.

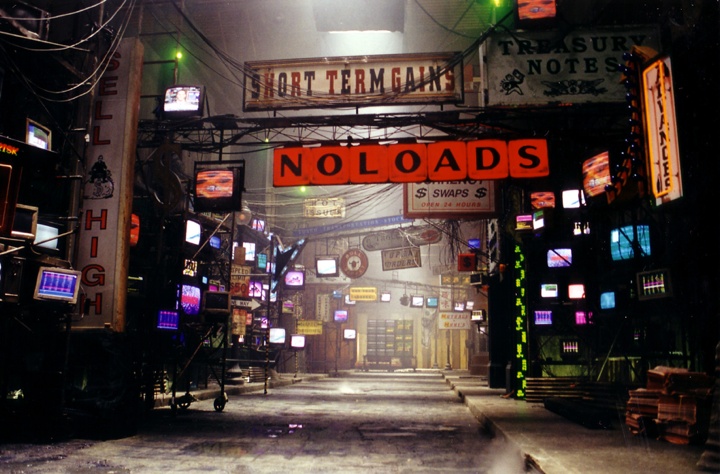

Final light set for First Union Bank commercial (done at Industrial Light & Magic). Courtesy of Michael Goldman.

Kirill: If there’s such a thing as a typical production, when does your involvement usually begin?

Michael: On a big feature production, on the scale of Iron Man or Star Trek, we start early. As an Art Director I will work on the project for between seven months to a year, and I usually start around five months before the principal photography begins. We set up the art department, start doing the illustrations and conceptual drawings and models, and all the while the script is changing. The first couple months of prep we deal with outlines and early scripts and towards the end we’re doing a lot of drafting up working drawings and set construction. Art directors mange all these steps.

Kirill: How much of this is overlapping with the main shooting phase?

Michael: We’re designing, building and striking sets throughout the whole production. A big production usually rents a bunch of stages at a studio, and we keep rotating through them, building on several stages weeks or months ahead of the shooting time and then we strike them after they finish shooting and build the next one. When possible, we bring the director and other key players in ahead of time to comment on the progress of the sets and make adjustments as we build. On the first day we shoot a new set we are always there to “open the set” and make sure the director, producers and have what they want. Then we head out and keep working on what’s coming up the following weeks. It’s kind of leap frogging between stages. Depending on the size of the movie we might end up filling every stage at a studio two or three times.

Star Wars 1 – video game commercial (done at Industrial Light & Magic). Courtesy of Michael Goldman.

Continue reading »

![]()