In the last post I talked about deliberate brevity – taking time to think through a problem and finding a solution through concise coding. But writing as little code as possible is most certainly not my goal these days. In fact, as a goal unto itself it sets you onto a very dangerous path.

Estimating roughly, I spend 10% of my time writing code and 40% of my time debugging it (including code written by others before me). Let me repeat that again. I spend 4x as much time reading and tweaking existing code than writing new code. I’m not that interested in writing tersely. I’m much more interested in writing clearly, for the benefit of everybody that is going to be looking at that code down the line – future me included.

At times we are faced with complex problems. It’s only natural to come up with complex solutions. Complex solutions create an illusion of being a master of your domain, impressing your peers and beefing up that pitch to bump you up to being the “senior engineer, level 5C” for the next promo cycle. “Nobody knows that module better than Bob. In fact, Bob is the only one who understands it at all.” I’ve seen enough code written by Bobs. To be honest, I don’t like where the Bobs of our world are taking us.

It takes time and patience to distill a solution to its most vigorous form. And it takes skill and humility to remove complexity from the solution. To practice the craft of writing clear code. Code that is clear to read, clear to maintain and clear to evolve. Finding clear solutions to complex problems is the ultimate mark of our craft. It’s time to stop admiring complexity and start appreciating clarity.

I’ve spent four days at the beginning of March this year working on immersive hero images in our app. I touched around 250 lines of code all in all, mostly adding new code but also modifying or deleting a few dozen existing lines. And that’s pretty much all I did in those four days. Sure, there were a couple of small meetings here and there and an occasional code review, but overall I’d say that I’ve spent at least 8 hours every day working on this feature. Overall my total output was less than eight lines of code per hour. That sounds not very productive of me, I know.

Recently I find myself not really writing a lot of code. Instead of diving straight into the editor, I think. And I think. And I think some more. I literally sit there staring at my desk. I get up and walk around the room. I take a break and browse the web (but don’t tell my managers about that). And then I push it out to the next morning.

On any given day I find myself spending, perhaps, 10% of the time writing code, 40% of the time debugging it and 50% of the time thinking about it. It certainly seems like a big waste of my time. I should be down there in the editor, banging out line after line, method after method, class after class, throwing it at the device and seeing what’s happening. You know, walking the walk.

But I’ve walked that walk before. It felt good to always be moving and it felt great to always be moving fast. These days I prefer to move slow.

I like to think about this as deliberate brevity. A long long time ago, a French mathematician and philosopher Blaise Pascal said “Je n’ai fait celle-ci plus longue que parce que je n’ai pas eu le loisir de la faire plus courte.” Translated loosely, “I have made this longer than usual because I have not had time to make it shorter.”

I enjoy taking time to make my changes brief and vigorous. In the words of William Strunk, “When a sentence is made stronger, it usually becomes shorter. Thus, brevity is a by-product of vigor.” I believe that every line of code needs to fight for its right to exist in our code base. I believe that every comment needs to fight for that right as well. I immensely enjoy code reviews where one of my teammates points out how I can cut out even more code and make things even simpler, but without losing the overall clarity of what the code is doing.

I am indifferent to productivity tools in general and to debates on which IDE makes programmers more “productive”. When you spend five times as much time thinking about the code than writing the code, the number of shortcuts, templates and auto-completion becomes quite irrelevant. I don’t measure my output by words of code per second or lines of code per minute. I measure my output by the robustness of the path I’m paving, over weeks, months and years.

When you spend half your day thinking about the code, every distraction hurts. Open office plans that proclaim to foster spontaneous exchange of ideas are creating a never-ceasing cacophony of distractions that is actively disrupting the most precious resource we have to offer our employers – our brains. Until they come with a thinking-time switch that envelopes you in a literal cone of silence, they must not progress beyond the corporate facilities planning spreadsheets. I realize that it’s a bit late for that.

Don’t aim to impress me with how fast you can churn out new code. Don’t tell me that it will all be done by the end of business day. It rarely happens, and when it does, I know I’ll find myself wading through vast reams of that code in a year’s time (when you might have already gone to some other project), trying to understand why it is, in fact, so vast. Don’t ask for permission to spend time thinking. And don’t think that spending all that time thinking only to write fewer lines of code makes you a less productive programmer. Be concise. Be brief. Be vigorous.

In the epilogue of “The Mythical Man Month” Frederick Phillips Brooks says that there are only a few people who have the privilege to provide for their families doing what they would gladly be pursuing free, for passion. I am quite lucky to consider myself to be among those people. In a hypothetical situation where I buy a lottery ticket and win the 8-digit prize, I’d most probably find myself not necessarily continuing programming each day, every day. Having said that, it’s quite nice to be employed doing what you love to do. But, as with all things in life, you can’t expect a steady level of “enjoyment”.

Years and years ago (I’m talking last century) when I was studying computer science at a university, one of the mandatory courses included a homework exercise doing a stopwatch in assembly. You had to write a program that gets user input in mm:ss format, and when the user hits Enter, starts counting down to zero. I think there was also the part where you had to track keyboard input and stop the timer, but my memory fails me at the precise details.

I hated that exercise. I absolutely abhorred the very notion of dropping so low to the metal. You know, pixels are my people. So I waited. And waited. And waited. Until the very last evening before the morning when the homework was due. And then I schlepped to the computer lab, plopped into the chair and considered the bleak night in front of me.

As a parent I tell my kids to not postpone the exercises and chores they don’t like until the very end. I tell them that if they start with things they enjoy, they end up with a clump of boring, tedious and dull things at the very end. Of course back then I didn’t want to be quite as reasonable. So as I forced myself to start with something, anything, anything at all, I picked up the less mind-numbing parts of the exercise.

I started with processing the user input. Something like look at the character that was just typed and beep if it’s not a digit. Then proceed to mirror the character on the screen and advance the cursor. Then, at least after one digit, also accept the colon. Then tweak the input validation to only accept digits from 0 to 5 in the next slot. Then tweak the input validation to only accept Enter after exactly two digits after the colon have been provided.

And then I stalled for a bit more time, tweaking the input processing routine to accept additional Enter strokes to treat them as decrementing one second from the timer. Which brought me to writing another routine that would update the currently displayed value, handling the transition from :00 to :59 state.

I distinctly remember the depression I felt at the very thought of tracking and syncing with the system time facilities. I tried to postpone it as much as I could. It was the farthest away from the pixels, and I left it until the very end. And then a wonderful thing happened.

As I kept peeling off those onion layers, I kept on getting a continuous stream of visual progress confirmation. My routine for accepting the initial timer value was working. My routine for rejecting invalid inputs was working. My routine for decrementing the current timer value was working. And as I kept peeling off those onion layers, and as I got the the very last piece, I found out that it was actually quite manageable. There was only this last thing to cross off the list. I did it and I didn’t even notice how smoothly it all went.

Fast forward to early March 2015 and the code base I’m working on. It’s been around for a while. I’ve been on it for a while, almost five and a half years. It’s seen some major redesigns. In fact, I can’t think of a single module or class in it that hasn’t been gradually (and completely) rewritten at least once. And it has a lot of baggage.

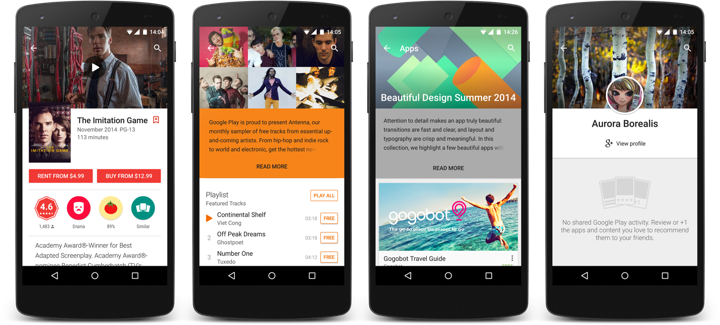

I’ve briefly mentioned this the last time Chet and Tor hosted me on their podcast. As we started down the path of bringing our app into the Material world, we had two choices. We could graft the various aspects of Material (keyline grid, in-screen animations, cross-screen transitions) on top of the code base that was, frankly, simply not built to be that flexible. Or we could rebuild the foundation (ahem, yet again) with an eye towards that flexibility and then bring those elements in.

Rebuilding the foundation is at most times a long, dull and unexciting process. You know that at some point in the hazy future when it’s all done, it will enable all these wonderful things (and you hope that by the time you get to that hazy future, the design hasn’t changed in any major way). But for now, and perhaps for a while, the things you’re doing are not resulting in any kind of user-facing improvements. If anything, the deeper you dig, the worse it gets for the overall instability of your code base (aka Things You Should Never Do – except when you really have to). And so you dig, and you dig, and you dig. And you get closer to that hazy future. One step at a time.

And then at some point you look at what you’ve built, and you see that it’s ready. And you make a 150-line code change and suddenly you have the hero image extending all the way into the status bar on the details page. And the next day you make a 40-line code change that builds on top of that and you have the same functionality on the profile page – because they share the same skeleton structure that you and that other guy on your team has just spent the last four months rebuilding from scratch. Oh, and there were these ten people scattered all across these other teams that built the components that enabled to rebuild that skeleton structure in only four months. But I digress.

And then the next day you have a 50-line code change that brings the same functionality to a more complex context that looks exactly like those other two you already did, but instead of a simple RecyclerView it’s a RecyclerView in a ViewPager that has a single tab which hides the tab strip where you don’t even know if you’ll need to display the hero image until after the second data loading phase that happens when you’ve already configured the initial contents of that ViewPager. But you didn’t start straight away from this complex case. You started from a simpler case, hammering out the details of how to even get into the status bar. And when you got to the ViewPager context, you were able to concentrate on only that one remaining case.

And so you go. Across the landscape of your code base. Sometimes it just flows and you don’t even notice how yet another week flew by. And sometimes you look at this craggy cliff and you just want to turn and run away. But instead, you work at it. One step at a time. And before you know it, the cliff is behind you. And then you take the next step. Because the next cliff is waiting.

Continuing the ongoing series of interviews with creative artists working on various aspects of movie and TV productions, it gives me great pleasure to welcome John Lavin. In the last few years he worked as the production designer on “Your Sister’s Sister”, “Touchy Feely”, “Lucky Them” and the recently released “Laggies”. In this interview John talks about splitting his time between feature film world, interior design projects and illustration work, the smaller scale of independent movie productions, approaching the script and translating it into environments that live and breath around the cast, the changes we’re seeing in how and where people consume content and the effect it’s having on the world of indie films, and a deeper dive into the particulars of “Your Sister’s Sister” and “Laggies”.

Kirill: Please tell us about yourself and your busy professional life doing feature film work, interior design and illustration work.

John: A lot of that is driven by me living in Seattle rather than in, say, Los Angeles. There’s not a lot of feature production happening here, and I have always had the idea that it’s better to be a generalist than a specialist. It works better for me to have a lot of irons in the fire, to work in different directions.

I was in New York, going to graduate school for painting. I was living there, doing jobs as a retail display person. I worked doing the windows at Barneys, and from there moved to art department work, doing photography, video and other projects. It was a combination of retail display, art department and fine arts. I used them all in different ways, and that’s the background that I’m coming from.

When I moved back to Seattle, I did a lot of work as retail designer. My art work translated into illustration work when my second child was born. It was a better economic model for a working parent to get paid upfront for things instead of hoping to sell things later.

And as far as all these fields, it’s really all the same thing. It relates really closely. There’s not that many people that I work with, or that I know, who work in all of these fields, but they’re actually very similar. It’s all about making something look good from a certain point of view. It can be a camera, or a person standing on the street, or walking into a room and having the sense of the space.

Kirill: I’d imagine it also exercises different parts of your brain.

John: Absolutely. The current project that I’m working on involves a lot of set design and a lot of space design. I’m trying to make modular set pieces that can work for different shoots at different times and be reconfigured. It’s about spatial organization and design, more than many other jobs. And other jobs are about visual sensibility or painting sensibility.

Kirill: It sounds like you’re also enjoying the physicality aspect of it.

John: I sure do. I really like painting. I like sculpting. I like making and faking.

On the restaurant set of “Laggies”. Courtesy of John Lavin.

Kirill: If I jump a bit forward in the interview to your feature work, what do you think about productions driven by virtual sets created with digital tools?

John: I came to work on indie films, and I recently heard them being described as “people talking in a room”. I have an affinity for a movie of that scale.

I like to watch a big movie as much as the next guy, but there’s a certain thing that I don’t relate to well and don’t have a lot of interest in. It’s the CGI ‘Battle that Decides the Fate of the World’ that happens in so many large films. You have two massive armies engaged in a huge battle, and the whole thing feels so completely bogus. I don’t have any interest in that.

I like the idea of a smaller scale feel, and that’s the kind of film that I’m more interested in working on – compared to the effects-driven film.

Continue reading »

![]()