As I wrote late last year, software is never quite done. And so goes yet another year tweaking the presentation layer on this very site. Back in 2014 I’ve switched to using 2x / retina images on modern screens, going back to the archives and resourcing all the images in the interviews that have been published until then. From that point on, all the interviews published here showed higher-resolution images when appropriate. And yet, that wasn’t enough.

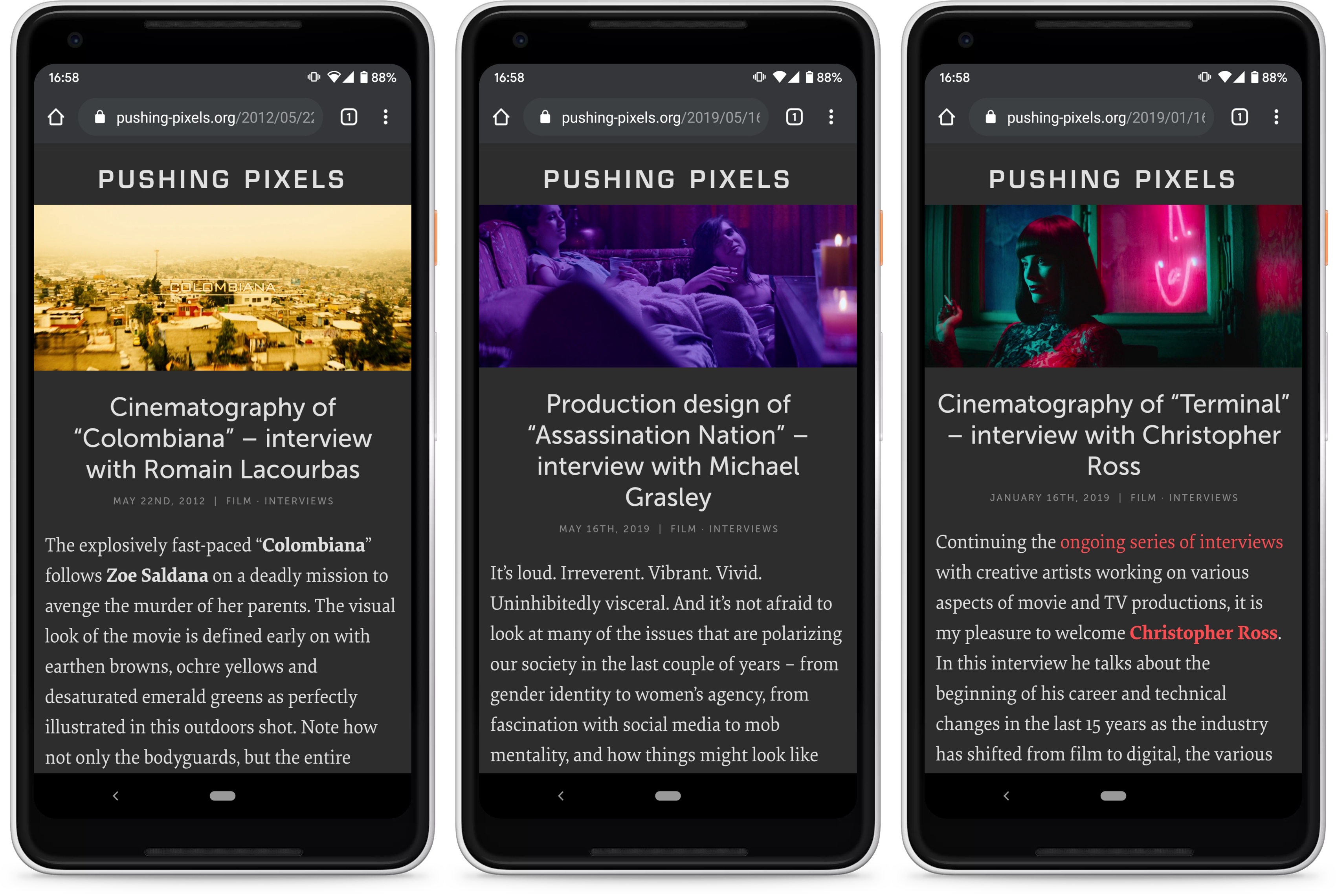

The film medium is by its very nature a visual one. Stills from film productions, be they movies or TV shows, demand the same full-width treatment as the production itself. I’ve spent most of my summer going back to older interviews and resourcing all the images (yet again) to even higher resolution. Now those stills are displayed in full-width, edge-to-edge format no matter what device you’re viewing them on. In addition, I’ve started to switch all the interviews to use the leading hero image that is displayed before the title block. Here is how it looks like on smaller, phone-sized screens:

And this is how it looks like on larger, laptop / desktop sized screens:

This is probably it for the 2019 edition of tending this little web garden of mine. What will the year 2020 bring?

Stay tuned for a more technical overview of how this can be achieved in WordPress.

Continuing the ongoing series of interviews with creative artists working on various aspects of movie and TV productions, it is my pleasure to welcome Learan Kahanov. In this interview he talks about collaboration between different departments, technological changes and breaking the political status quo in the world of storytelling, the multiple roles that a cinematographer must assume on set, and the importance of story. Around these topics and more, Learan dives deep into his work on “Madam Secretary” that is in the middle of its sixth and last season as we speak.

Learan Kahanov on sets.

Kirill: Please tell us about yourself and the path that took you to where you are today.

Learan: I was interested in the captured image since an early age. I played with cameras all through my school years. My mother is also a fine artist, and she went to art school when I was in middle school. So I found myself being dragged along to the darkroom as she did a minor in photography. While she was learning photography, I was learning photography. Eventually I got a camera and started shooting black-and-white stills.

After my mother graduated, she started teaching drawing classes. We had our own art studio, and she would hire models that would pose for her drawing classes. She offered me the opportunity to take pictures and I could do my own stuff.

I was always interested in pictures and imagery. I don’t actually remember the moment where it clicked that I wanted to be a filmmaker. Throughout growing up and in high school I worked at a Children’s Museum and I taught other younger kids how to do photography and photograms. Then I got into some video work and taught the kids how to use the video cameras, and we would make these little short films at the Museum. That’s what really sparked my interest and I quickly realized that filmmaking was the direction I wanted to go.

I went to my state school for photojournalism in order to create a portfolio to get into NYU film school. When I was at NYU, I went right away to all the professors and said that I have no interest in directing. I just wanted to do cinematography.

I think a lot of it came out of how I was raised. I’m first-generation American to Israeli parents; my mother being a fine artist and my dad didn’t have a typical job either. It was seeing the world in a little bit of a different way than the people I grew up with.

I wasn’t necessarily ever a cinephile or someone who studied film as a kid. But I was always interested in the emotional response of an image and the way an image could tell a story. That’s my memories of it as a kid and as a young adult.

When I was at NYU I shot as many films as I could. I also worked as an electrician and eventually a gaffer in the indie world in New York because I was always interested in lighting. Even the photography I was doing in high school and in college was a little more towards the art side of photography rather than the documentary. I was never the guy who walked around the street with a camera and did street photography or documentary style. For me it came more from a narrative storytelling point of view, and that’s why it was an easy transition to try to get into movies, music videos and commercials, and less documentaries.

My early career was basically shooting as many student films and indie films that I could, as well as working professionally as a gaffer. I always felt that I won’t always end lucky enough to have a gaffer who knows how I want things to be lit, so that was my angle – advancing through lighting.

Around 1999-2000 I decided to make a strong push to DP full-time. It was a lot of hard work, a lot of “no”‘s, a lot of low budget projects that did not make me a lot of money. I ended up shooting about a feature a year for eight years, and around 2007 I got into the Camera Union in NY. That parlayed into other television work, commercials and bigger projects, leading me to where I am today – finishing up the sixth season of “Madam Secretary” on CBS. I started the job as A-camera operator and additional cinematographer, and then on the third season took over the show fully.

Cinematography of “Madam Secretary”. Courtesy of CBS Broadcasting.

Kirill: If I went to your set today, what do you think would be the most unexpected or surprising thing for me as a viewer that knows only how the final product looks?

Learan: I wouldn’t say this would be specific to my set, but to film sets in general. It’s the amount of choreography that goes into making that final product, and the dance that we all do between the departments. Everyone has this special skillset that can work beautifully in tandem with everyone else to create this piece of art, or piece of entertainment, or whatever that product might be – however artistic or commercial you might want to call it. It’s amazing to see that team work, that collaboration in an industry that is far from democratic.

Filmmaking is not a democracy in its hierarchy, but it can’t be done without collaboration. It’s quite a beautiful thing how there’s all these levels of workers, bosses, managers and artisans – from producers to the directors to the production designers, and all the way down to the set technicians and PA’s. On the best jobs there’s such a synergy and a symbiotic way of working, it’s truly magical. You have to pull back the curtain to see how many people are involved, and how they relate to each other. It becomes a family.

We go to work and you become close, because you’re spending a lot of hours together. Often it’s more hours than most people do when they’re at their everyday job working in an office. It becomes a family, and I think that surprises a lot of people. It’s often separate from the final product of what are we creating. It’s that passion for creating something that everybody shares, whether it’s someone whose family’s been in the industry for many generations to a person like me who has no family in the industry, somebody who just decided I’m gonna go for it and break in.

Kirill: Looking at these first 20 years of your professional life, do you think it’s easier to get into the industry nowadays? The cameras are getting better and cheaper, and there are so many productions of so many different sizes. Does it feel like if you were starting today, maybe it would have been accessible?

Learan: A few months ago I went and talked to a class at School of Visual Arts in New York. I talked about my career, how do you break into the industry and what have you. My take is that it’s definitely more accessible these days to produce something- short film, TV pilot, feature film. It’s definitely easier and more accessible to create something.

That being said, I don’t know if it’s any easier to get into the industry. I think the industry still in many ways, both the good and the bad, is stuck in its ways of how things are produced, funded and distributed. You have all these streaming services, digital acquisition channels and digital distribution channels. There’s an increase in need for content, an accessibility for content and a yearning for content. My middle schooler son can make a short film and put it on YouTube for anyone who wants to see.

But as far as the industry is concerned, I think it’s still as difficult. The politics have not gone away – the who you know, and the where you’re from, and the where you’re going. There’s a lot of talent out there and talent alone isn’t going to get you there. In that sense the industry hasn’t changed that much, as far as breaking in.

The great part about these times is the accessibility of it all. The cameras are so accessible. You can do nonlinear editing on a laptop, along with sound design and visual effects work. It’s opened a lot of doors for a lot of young filmmakers, and for not so young filmmakers who want to break into the business later in life. The question is how do you “make it”. There’s a little bit of timelessness to how tough things still are.

I do think that’s true with any creative industry, whether it’s filmmaking, music or dance. There’s the old saying of where talent meets opportunity. That’s still true to this day. The great thing about where we are now is that because of the accessibility of the cameras and the gear, a lot more talented people have a voice, and can put their ideas and their stories out in the world. That was a lot harder to do 20 years ago, just for the simple fact that we all shot on film. There weren’t that many video cameras, especially any video cameras of high quality. It was a more select group of people who had that access.

Cinematography of “Madam Secretary”. Courtesy of CBS Broadcasting.

Continue reading »

Continuing the ongoing series of interviews with creative artists working on various aspects of movie and TV productions, it is my pleasure to welcome Carolina Costa. In this interview she talks about technology changes in the field of cinematography, discovering new voices as a viewer, the balance between technical and artistic aspects of her craft, and how she chooses her projects. In between these topics and more, Carolina talks about her work on this year’s “Babenco” and “Hala”.

Carolina Costa on an AFI Panel at the Sundance Canon Creative Studio.

Kirill: Please tell us about yourself and what brought you to where you are today.

Carolina: My name is Carolina Costa and I’m a director of photography. I’ve done documentaries, commercials and music videos, but I really like to focus my work on narrative fiction work. It’s interesting because it takes me back to when I first started as a journalist.

I’m originally from Brazil and I’ve been moving around the globe. I lived in England for a few years, then in Los Angeles and now I’m in Mexico. Back when I was in Brazil, I studied journalism and I worked as a photojournalist. Still photography was my first contact with the world of capturing image – I was photographing the reality around me. I grew up in Rio, right next to one of the biggest favelas, and it’s a violent city. My first interest was to portray the kids around the area.

Moving into motion pictures came from that as well – through the frustration of not being able to change my environment. I felt like movies could do that, more than what I was doing with photojournalism. I felt like people could go to the theater and forget how bad their lives were, or they could go and connect to a character on the big screen and through that experience they could deal with something that is a little harder in their life.

When I first moved to London I started working as a camera assistant. Then I moved up the ranks of the camera department and eventually graduated to being a director of photography. Then I went to do my Master’s degree at the American Film Institute, and that was the moment I saw myself as a director of photography with all the necessary tools.

Kirill: Is there anything in particular that you remember from being on set in your first couple of productions?

Carolina: The other day I found the photos from the first film set I worked on as a camera assistant, and I looked so serious. I think I was just nervous, trying to do a good job. I knew it was going be a long way to the top, with long hours and very little sleep. You’re fighting for a piece of the spotlight, because there’s so many good people out there.

It wasn’t glamorous or anything. It was quite clear to me that it was a lot of hard work. When I started as an AC, the days were long and the nights were short. I’d catch a train then a bus, and would be the first one on set to clean everything. I’d sleep maybe three hours every night. There were days that I would question what I was doing, but it was clear to me that I wanted to be there.

I always tell people who start working with me, that you need to know if you really want to do this. There’s zero glamour to it [laughs], and it’s a lot of hard work. But I feel that if you truly have that passion, there’s just nothing like it. When I’m on set I’m truly myself. When I’m outside of set, sometimes I find it hard to find my footing. That’s also part of the experience. You accept the little sleep and long hours.

Cinematography of “Girl on the Side”. Courtesy of Carolina Costa.

Kirill: Do you think it’s easier to get into your field these days, as cameras are getting better and cheaper, and some people even shoot things with their phones?

Carolina: That’s really exciting. When I first started shooting music videos and shorts, it was right around the time when 5D, 7D and similar cameras came out. That new equipment had shallow depth of field and it was affordable. It gave freedom to someone like me that couldn’t go and shoot a short before.

Previously you would need to go to Fuji or Kodak, and beg them to give you some film. Then you’d go to a lab and try to persuade them to process it for you. One of my early shorts was done in a lab as a back-end of someone else’s production.

I remember that period when those cameras came out. I went out and experimented with shorts and music videos, figuring out how to light and do other things. That is still going on today. You can go with your iPhone and shoot something, and it is valid.

With all this talk about digital taking over, I thought that maybe voices we haven’t heard before would now be heard. Where I come from, the famous movies are all about the slums and the violence in those areas, but generally you never see a movie that is made by someone actually from that place. It’s usually middle class and upper middle class talking about those social circumstances.

That’s what excited me most about those cameras becoming accessible. I was looking forward to those new voices coming out. But very little is coming out of it, and I can’t put my finger on why. You have more cameras and they’re cheaper, and people can experiment, but I still feel that it’s an industry that is reserved for very few people, and that hasn’t changed. I wish the excitement about the new digital format had pushed the other side as well, but it hasn’t really. I feel like it’s a shame, because it offers that possibility.

Recently I saw a guy here in Mexico and he sent me a cut of a documentary he shot on his phone. It’s crazy. He filmed real narcos, and he was right in the middle of it with the guys, the guns and everything. I haven’t seen anything like it. Of course, there’s no way you could bring an actual film camera and lights. We talked about how he could make the cinematography better and more interesting, but I told him that he shouldn’t listen to me. He should go and do what he’s doing.

It’s generating interesting projects and I wish there were more of them.

Kirill: From my perspective as a viewer, sometimes I ask myself how do I discover those new voices. It can feel a bit overwhelming and fragmented to navigate the landscape of visual storytelling, be it features, documentaries or shorts. How do you go about it as a viewer?

Carolina: I suffer like everybody else. We see the same billboards and the same posters. I feel like everybody watched “Roma” because there was so much advertising for it [laughs]. You couldn’t miss it, it was stuck in your mind. I’m human, and I’m part of the same society.

I have friends in many places in the world. The other day I sat down with a friend from Iran, and I asked them to give me names from Iranian cinema. Then I spent the whole weekend watching their work. Afterwards, I reached out to friends and colleagues from different places, cultures and upbringings. That’s how I find things to watch.

I’ve also been doing master classes, and I feel that the contact with younger generations has exposed me to a bunch of cool stuff that I would not necessarily be in tune with.

Cinematography of “How To Make a Bomb”. Courtesy of Carolina Costa.

Continue reading »

As usual, DragonCon comes to Atlanta over the Labor Day weekend. These are my personal highlights from the opening parade this year.

![]()

![]()